If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?

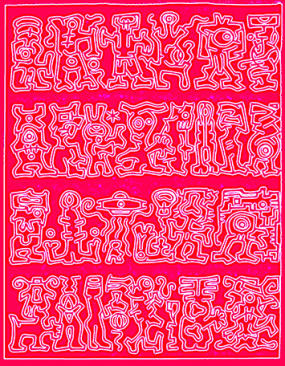

Matthea Harvey Graywolf Press ($25) by Renoir Gaither If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?, Mattea Harvey’s fifth collection of poetry, combines photographs, silhouettes,

Matthea Harvey Graywolf Press ($25) by Renoir Gaither If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?, Mattea Harvey’s fifth collection of poetry, combines photographs, silhouettes,

Georges Perec Translated, introduced, annotated, edited and indexed by Philip Terry and David Bellos David R. Godine ($16.95) by Jeff Bursey To some readers, the

Soumitra Chatterjee Translated by Arunava Sinha Supernova ($6.50) by Graziano Krätli Soumitra Chatterjee was for Satyajit Ray what Marcello Mastroianni was for Federico Fellini, Jean-Pierre

Susan Sherman Wings Press ($16) by Jim Feast While Susan Sherman’s book of stories Nirvana on Ninth Street is certainly a refreshing and readable volume,

John Carr Walker SunnyOutside ($13) by Beth Taylor In this first collection of short stories, John Carr Walker studies the psyches and stumbles of men

Lydia Davis Farrar, Straus and Giroux ($26) by Brooke Horvath With the 122 stories comprising Can’t and Won’t averaging two-and-a-half pages each, Lydia Davis can

An Aladdin’s Cave of Delights by Lydia Wilson A Canon? The New York Review of Books has an authority which gives a children’s book published

by James Naiden She lived for just over sixty-three years (1912-1975), her last three decades as an active writer who published fifteen books in her

INTERVIEWS Bald New World: An Interview with Peter Tieryas Liu Interviewed by Berit Ellingsen In a dystopian future where everyone is bald, two filmmaker friends

Editor’s Note: Leslie S. Klinger and Neil Gaiman appeared at Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis on November 9, 2014, to discuss Klinger’s latest book,