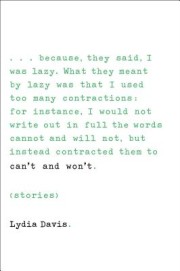

Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ($26)

by Brooke Horvath

With the 122 stories comprising Can’t and Won’t averaging two-and-a-half pages each, Lydia Davis can make István Örkény, the Hungarian writer famous for his “one-minute stories,” seem downright verbose. Readers familiar with Davis’s previous work will notice few changes here of style or sensibility, though there are more exceedingly short stories than previously (several under two dozen words each, many less than a page long). New this time are stories recounting dreams and “dreamlike waking experiences” (both hers and those of family and friends) and stories reworking material taken from the letters of Gustave Flaubert (Davis having published a few years ago a new translation of Madame Bovary).

If Can’t and Won’t is a refinement of the author’s less-is-more aesthetic, the collection also contains a number of longer efforts. The longest, at twenty-nine pages, is a “letter” thanking a foundation for a research grant the letter-writer hoped would get her out of another miserable year of teaching. Another epic effort of sixteen pages describes the day-to-day activities of three cows in a nearby field, while “Local Obits” catalogs in nine pages what made sixty-eight recently deceased persons special: “Helen loved long walks, gardening, and her grandchildren. Richard founded his own business.” Among the shortest stories are “Contingency (vs. Necessity),” sixteen words about a dog that could belong to the author but does not, and “Ph.D.,” which reads in full: “All these years I thought I had a Ph.D. But I do not have a Ph.D.”

Between these extremes are whimsical noodlings, found texts, remarks overheard while traveling that give the lie to Gertrude Stein’s contention that “remarks are not literature,” possibly true anecdotes gleaned from reading, letters (to a “Frozen Peas Manufacturer,” the Harvard Book Store, the “President of the American Biographical Institute, Inc.”), and what Davis described in a 2008 interview with The Believer as “meditation, logic game, extended wordplay, diatribe.” In one, a woman receives a box of chocolates and dithers over how and with whom to eat them; in another, a woman named Davis does and then does not wish to sell a rug to a man named Davis who both does and does not want to buy it. In a third, Hungarian playwright Ödön von Horváth finds a dead hiker in the Bavarian Alps in whose knapsack is a postcard, “ready to send, that read, “Having a wonderful time.” The two-sentence “Her Geography: Illinois” notices a woman who “knows she is in Chicago” but “does not yet realize that she is in Illinois,” while “I’m Pretty Comfortable, But I Could Be a Little More Comfortable” offers us seven pages of complaints (“My thumb hurts. A man is coughing during the concert”).

As Davis told Dana Goodyear in a recent New Yorker profile, her stories offer us “isolated events in a context of mystery,” constructs that are “a little different from reality.” They read, often, like Zen koans written by a monk who grew up on Samuel Beckett and Russell Edson (two of her acknowledged influences), their meaning, Davis avers, something she herself has never liked to think about. Or say these stories are the verbal equivalent of a series of paintings by Josef Albers or Mark Rothko, before whose work one thinks what, exactly? What, after all, are we to think about a story in which the five-sentence “plot” turns on a maid’s unwillingness to remove a vacuum cleaner from the hall even though a priest (possibly the Rector of Patagonia) is coming for a visit? Or a story in which, during a “long phone conversation” with her mother, a woman shuffles the letters of the word “cotton” into various permutations (“nottoc,” “coontt”)?

As for me, I am thinking about the boy who arrived at my door earlier today with a fruit tart that, he claimed, contained an excellent, ready-to-submit review of Can’t and Won’t. I looked, but found no review. “Too bad,” said the boy. “It was a peach.”