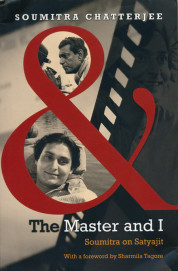

Soumitra Chatterjee

Soumitra Chatterjee

Translated by Arunava Sinha

Supernova ($6.50)

by Graziano Krätli

Soumitra Chatterjee was for Satyajit Ray what Marcello Mastroianni was for Federico Fellini, Jean-Pierre Léaud for François Truffaut, or even (though in a far less problematic way) Klaus Kinski for Werner Herzog—an early and fateful discovery meant to become a source of inspiration, an alter ego and a close friend (or, in Kinski’s case, a “best fiend”). Now approaching eighty, with two cinematic careers under his belt (one largely shaped by his thirty-five year collaboration with Ray, the other following the filmmaker’s premature death in 1992) and a growing presence on stage (crowned, recently, by his first Shakespearean role in a Bengali adaptation of King Lear), Chatterjee is a cultural institution in Kolkata, like the used bookstores or the Coffee House on College Street. The latter venue, conveniently located opposite Presidency College and down the street from Calcutta University (Chatterjee’s alma mater), has long been a favorite meeting place for students and intellectuals, and represents one of Kolkata’s main cultural hubs. Chatterjee recalls how, in the mid-1950s it was for him and his friends like a second home, where adda sessions, or intellectual debates, lasted for hours and focused largely and most passionately on (Bengali) literature and theatre. Cinema, on the other hand, was not taken “all that seriously” yet, and Chatterjee himself “harboured a certain unwillingness to act in films” as a result of his “warped ideas” about cinema, and Bengali cinema in particular. What changed everything—including Chatterjee’s prospects—was the filming of Pather Panchali, one of the most popular and beloved novels in Bengali literature, by a commercial artist who was better known, at the time, as the son of a famous writer and illustrator.

The circumstances of his first meeting with the man who made this change possible are representative of the small, intimate world of Bengali cinema (and culture) at the time. A friend met in the street introduced him to a man who turned out to be Ray’s assistant director and was looking for someone to interpret the lead role in Pather Panchali’s sequel, Aparajito. A few minutes later the three are on a bus bound for the Lake Avenue residence of the Master himself, where the young aspiring actor finds in the barely older but already famous director a kindred spirit. Even though he proved too tall for the role of young Apu (he would have to wait a couple more years before Ray chose him for the title role in the last film of his famous Trilogy), the encounter marked the beginning of a lifelong association and one of the longest and most fruitful collaborations in the history of cinema, resulting in fifteen films in thirty-five years and including such classics as The World of Apu (1959), Charulata (1964), Days and Nights in the Forest (1969), and Distant Thunder (1973), as well as a 1987 documentary on Ray’s father.

Coming soon after two other intimate portraits of the man known to family and friends as Manik da—those of Ray’s still photographer Nemai Ghosh (Manik Da: Memories of Satyajit Ray, 2011) and wife Bijoya (Manik and I: My Life with Satyajit Ray, 2012)—The Master and I strives to subdue the hagiographic impulse and draw a more objective and nuanced portrait of a rich and multidimensional relationship. Despite its reverential and laudatory tones, awkward similes (“Like a good captain, he led from the front,”) and occasional repetitiveness (Ray’s “famous” or “trademark baritone” is mentioned no less than five times), the book achieves its goal largely thanks to the ample selection of behind-the-scenes anecdotes, most of them intended to illustrate the symbiotic character of the master-disciple relationship between the two. Thus we learn that, during the making of Charulata (“The Lonely Wife,” 1964), Ray’s adaptation of a novella by Rabindranath Tagore, Chatterjee had to change his handwriting “in order to write the way people did in the pre-Tagore era.” The fact that this change became permanent (something that Chatterjee refers to as an “extremely important incident in my life”) is almost paralleled, a few pages later, by Ray’s decision to alter the ending of the film as a result of Chatterjee’s criticism. An even more interesting example of their symbiotic relationship and its consequences is provided by Chatterjee’s reaction to Ray’s illustrations of his most popular character, private detective Feluda, in which he finds a resemblance to the filmmaker. To which Ray replies: “‘Really? Several people have told me that I’ve drawn him with you in mind.’”

Symbiosis aside, Chatterjee’s portrait ultimately reveals a more complex, multifaceted and contradictory personality than its devotional agenda is willing to present or acknowledge. On the one hand, it makes a point of showing Ray’s responsiveness to suggestions and criticism, explaining how he would read his screenplays to his close collaborators and ask for their reactions, and generally “listened to people’s opinions with genuine interest.” On the other it gives glimpses of a self-absorbed, maniacally dedicated, detail-oriented artist with a tendency to micromanage and work around the clock. Most revealing, in this respect, are Chatterjee’s remarks on the filming of Baksa Badal (“The Swapped Suitcases”), a comedy for which Ray wrote the screenplay based on a story by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (the author of Pather Panchali and Aparajito):

There’s another point that I might as well make directly. The facts that Manik da’s assistant Netai [Nityananda Dutta] was directing the film and had requested him earnestly to be present were not the only reasons for his visits. The truth is that Manik da never felt confident of the outcome when someone else made a film from his screenplay. He used to be nagged by anxiety, wondering whether the execution would be up to the mark.

Consistent with the overall tone of the book, Ray’s passing is dealt with in a dignified and understated way, without details about the event itself or references to the “inexpressible sadness” in which, according to Amitav Ghosh, Calcutta was sunk upon hearing the tragic news. Instead, once Ray is gone, Chatterjee respectfully abstains from any further references to cinema, ending his memoir with a diminuendo devoted to music, and Western music in particular, as an ultimate example of his Master’s expansive artistic personality and influence.