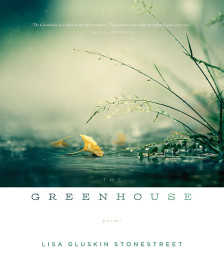

Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet

Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet

Bull City Press ($14)

by J.G. McClure

Until reading Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet’s The Greenhouse, winner of the 2014 Frost Place Chapbook Competition, I didn’t know what a chapbook could do. I’d read plenty of moving chapbooks, sure. But to create, in only twelve poems, an experience as urgent, as real, and as necessary as The Greenhouse is astonishing. The chapbook traces the complex and conflicted feelings of a new mother caring for her son. Stonestreet’s language—lyrical yet intimate, expansive yet concise—renders vividly the speaker’s own birth into a new life.

Take a look at “Like That,” which opens:

The first time

I leaned over and swept the tip of my smallest fingernail down intothe whorl of your ear (bigger than your elbow), and you yelped

in violation:

forgive meit is no longer my ear

(little boat, little shell I carved)flushing pink, even now, at the embarrassment, the satisfaction—

sliver-moon of yellow wax:

tiny victory.

While the opening line could lead into any number of sentimental and expected firsts, Stonestreet turns instead to something much more surprising for its ordinariness: removing a bit of earwax. In noting that the baby’s ear is bigger than his elbow, Stonestreet subtly shows how strange, how other this little body is. The baby, too, recognizes his distinct identity, yelping in violation of the boundaries of his body. The divide between the two—represented visually through the stanzification hinging on “forgive me”—is vividly realized: the child has his own life, and the mother must ask forgiveness from that which was once part of her. The assertion of both affection and possession in “little boat, little shell that I carved” is a wonderful insight into the tiny power struggle playing out between them. And yet, though separation is everywhere in these lines, so is connection: the baby feels both embarrassment and satisfaction at this intrusion. In this way, when the section lands on “tiny victory,” there’s a rich ambiguity regarding who, exactly, has been victorious: both mother and child have won and lost. The poem continues:

Lovers say, I did not know

where my body ended and yours began.

I did not know. Even yesterday when you laughed,reared back, your head

quick-snap against my upper lip, both of us

laughing and then me still laughing, eye-sting, drop of blood

at the crown of your head, panic—oh, mine. This morning

holding, rough/soft, drawing my tongue

up under my lip, compelling—Like that.

Again, we see the tension between separation and connection: the two are so connected that for a moment the speaker cannot tell the baby’s blood from hers. Again, Stonestreet’s talent for subtle yet telling moments shines: she is relieved to realize the separation between their bodies because it means that the baby has not been injured. But implicit in that feeling of relief is a deep connection: her care for the child is so great that she is relieved by her own injury.

There is much more to say about the poem, but for the sake of showing more of what The Greenhouse has accomplished, fast-forward to “After Dropping My Son Off at Preschool”:

The world slowly coming back. The luxury of stepping outside

myself

where is outside?

rehearsing for years nowI was a bubble, a greenhouse, a lens—

clear, like water, present like water, spreading, reflecting

ratcheting down the viewfinderself being a place encompassing a small boy

Step outside yourself, ma’am, and no one will get hurt

Nobody got hurt, not seriously.

It’s a goddamn miracle.

Stonestreet again immerses us in complexity. From the seemingly straightforward celebration of “the world slowly coming back,” we move into the “luxury” not of free time, but of stepping outside of the self. And even that complication is further complicated: the speaker is unsure where “outside” might be. The most recent years of her life are seen as mere rehearsal, practice toward a goal she still has not reached. In contrast, the speaker is much more confident in describing what she was; in describing this past, she gains access to more lyrically beautiful language and a more certain tone, asserting that the self was “a place encompassing a small boy.” But in doing so, we are reminded that the boy is no longer encompassed; he is now going off into the world. At this moment, the reverie breaks, and the ironic voice of the mock policeman enters. This humor grounds the poem in the contemporary, negating the risk of becoming too elevated, too Poetic (with a capital P). At the same time, it highlights the absurdity of asking someone to step outside herself—how is such a thing possible?—while reminding us, too, of the urgency of the need to do so. Impossible as the demand may seem, the speaker has managed it: “Nobody got hurt, not seriously.” Yet even at this moment of apparent triumph, the speaker can’t take credit or satisfaction: it is not her own accomplishment, but “a goddamn miracle.”

Once again, there is much more to the poem, far more than a review can cover. Suffice to say that The Greenhouse is one of those rare and wonderful chapbooks that is brilliant on the first reading, and even more moving with each return. It accomplishes in only thirty-five pages what so many books fail to do in a hundred. This is masterful work.