An Aladdin’s Cave of Delights

by Lydia Wilson

A Canon?

The New York Review of Books has an authority which gives a children’s book published by its imprint the instant stamp of a classic; this effect is emphasized by their red cloth spines which line up beautifully on a shelf to unite the variety of writing they present—an Everyman for children, as it were. The enterprise began in noticing that great books were continuously dropping off publishers’ catalogues to make room for the new, and many were also out of copyright and so could easily be reprinted and presented to a new generation. And so this is no library in the sense of a canon—there can be no in-print classic such as Alice in Wonderland or Winnie the Pooh. But this makes for a far more exciting Aladdin’s cave of delights, open-ended, ever-expanding, the editors seeking out forgotten gems or less famous works by popular writers with wholly unexpected treats spanning over a century and from all over the globe.

But it is not just the forgotten or minor works—quite the contrary. Jean Merrill’s The Pushcart War was on the School Library Journal’s list of “One Hundred Books That Shaped the Twentieth Century,” and is also endorsed here by Tony Kushner, who tells of the profound effect it had on him as a child. It appears in a 50th anniversary edition, though since it is set in 2026 it remains just as relevant to today; it should be mandatory reading for all the participants in the Occupy movement, with its tale of the powerless multitude’s non-violent resistance up against the biggest of opponents, literally. The most important book to Neil Gaiman, we learn in his beautiful introduction, is The 13 Clocks by James Thurber (perhaps better known for his fiction and cartoons at The New Yorker; also in the series is his The Wonderful O). J. K. Rowling tells of her admiration for E. Nesbit, an author still very much known about from TV adaptations (and more recently from Jacqueline Wilson’s

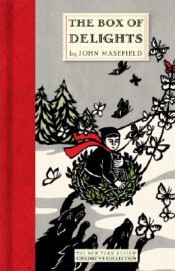

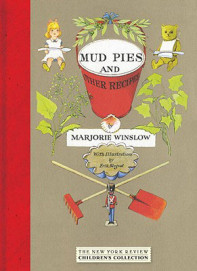

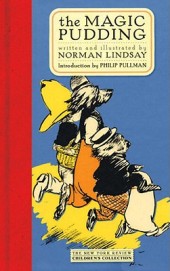

But it is not just the forgotten or minor works—quite the contrary. Jean Merrill’s The Pushcart War was on the School Library Journal’s list of “One Hundred Books That Shaped the Twentieth Century,” and is also endorsed here by Tony Kushner, who tells of the profound effect it had on him as a child. It appears in a 50th anniversary edition, though since it is set in 2026 it remains just as relevant to today; it should be mandatory reading for all the participants in the Occupy movement, with its tale of the powerless multitude’s non-violent resistance up against the biggest of opponents, literally. The most important book to Neil Gaiman, we learn in his beautiful introduction, is The 13 Clocks by James Thurber (perhaps better known for his fiction and cartoons at The New Yorker; also in the series is his The Wonderful O). J. K. Rowling tells of her admiration for E. Nesbit, an author still very much known about from TV adaptations (and more recently from Jacqueline Wilson’s  best-selling Four Children and It), which makes it all the more surprising that House of Arden makes a red-spined appearance. TV chef Sara Moulton writes that Mud Pies and Other Recipes persuaded her at age five that cooking must be fun; indeed, they all look like proper recipes, with the following delightful instruction at the beginning: “The time it takes to cook a casserole depends upon how long your dolls are able to sit at table without falling over. And if a recipe calls for a cupful of something, you can use a measuring cup or a teacup or a buttercup . . . What does matter is that you select the best ingredients available, set a fine table, and serve with style.” Philip Pullman introduces the Australian classic The Magic Pudding with the highest praise: “This is the funniest children’s book ever written. I’ve been laughing at it for fifty years, and when I read it again this morning, I laughed just as much as I ever did.” I could go on and on: children’s books are a source of passion for most writers, and New York Review Books has tapped this rich resource.

best-selling Four Children and It), which makes it all the more surprising that House of Arden makes a red-spined appearance. TV chef Sara Moulton writes that Mud Pies and Other Recipes persuaded her at age five that cooking must be fun; indeed, they all look like proper recipes, with the following delightful instruction at the beginning: “The time it takes to cook a casserole depends upon how long your dolls are able to sit at table without falling over. And if a recipe calls for a cupful of something, you can use a measuring cup or a teacup or a buttercup . . . What does matter is that you select the best ingredients available, set a fine table, and serve with style.” Philip Pullman introduces the Australian classic The Magic Pudding with the highest praise: “This is the funniest children’s book ever written. I’ve been laughing at it for fifty years, and when I read it again this morning, I laughed just as much as I ever did.” I could go on and on: children’s books are a source of passion for most writers, and New York Review Books has tapped this rich resource.

A Shared Culture

Another source one might plunder for ideas is the children in the books themselves. The sure-minded Henrietta in Henrietta’s House (written by Elizabeth Goudge in 1942—a worthy candidate for a future addition), has a specific idea of a library for children, listing twenty books which were obviously classics, in 1942 at least:

Henrietta took books from the shelves with a certainty that quite surprised the Old Gentleman. The Water Babies and Alice in Wonderland, Undine and The Pilgrim's Progress, Jackanapes and Little Women, The Fairchild Family and A Flat Iron for a Farthing, The Back of the North Wind and The Princess and Curdie followed each other into the basket with startling rapidity, followed by Uncle Remus, Hans Andersen, The Swiss Family Robinson, Andrew Lang's Blue Fairy Book, his Red One and his Green One, Mary's Meadow, Lob-lie-by-the-Fire, The Wind in the Willows and The Cocky-Olly Bird.

“Isn't that enough?” gasped the Old Gentleman.

“Yes, I think that's all,” said Henrietta, counting them.

“You seem to know exactly what is required,” said the Old Gentleman with much respect.

“Yes,” said Henrietta. “My father and I have often talked it over. We decided that if a person of my age had a library of twenty books those are just the twenty the person would want.”

Henrietta is not the only fictional child who might give indications of lost classics: E. Nesbit’s characters show great familiarity with Kipling and the Arabian Nights (and knowledge of her own 1902 classic Five Children and It is demanded for Jacqueline Wilson’s aforementioned contemporary novel). Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons< pepper their conversation with literary quotations; like Henrietta they are familiar with The Wind in the Willows, and also regularly refer to texts from Robinson Crusoe and Treasure Island to Keats and The Song of Hiawatha, taking in Greek and Norse mythology and other sea-faring tales. Roald Dahl’s Matilda shows an attachment to Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (though soon moving onto Dickens, child genius that she is).

Henrietta is not the only fictional child who might give indications of lost classics: E. Nesbit’s characters show great familiarity with Kipling and the Arabian Nights (and knowledge of her own 1902 classic Five Children and It is demanded for Jacqueline Wilson’s aforementioned contemporary novel). Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons< pepper their conversation with literary quotations; like Henrietta they are familiar with The Wind in the Willows, and also regularly refer to texts from Robinson Crusoe and Treasure Island to Keats and The Song of Hiawatha, taking in Greek and Norse mythology and other sea-faring tales. Roald Dahl’s Matilda shows an attachment to Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (though soon moving onto Dickens, child genius that she is).

These shared cultural landscapes shown by the children in past books may be partially lost to later readers, but only partially, and the link to Alice or Mowgli may well help to transcend the time lapse between publication and later readings. That spark of recognition—I’ve read that too!—that shared experience between character and reader, can overcome alienation of language, or customs, or social mores, bridging gaps and bringing characters to life. The revival of so many more in this series not only means more quality books are available for children, but also expands their range of inter-literary, historical, and cultural references. For better or worse, we lack a universal curriculum and consequent shared knowledge. In Western societies, familiarity with the Bible, the classics, and certain poets, philosophers, theologians, and historians was assumed for many centuries. An educated person could pick up on allusions to these central texts—an ability which has been mostly lost, a situation reflected in the numerous glosses now necessary for students to read the so-called “classics.” And so the study of older works is made into a chore, without the immediacy of recognition. (Of course what is gained from the loss of this universal curriculum is a broadening of education and cultural horizons; the canon was small and largely restricted to white, male, Westerners.)

Shared references are now formed of more contemporary culture—movies, music, bestsellers, and children’s books. Partly this is because parents pass on what they loved—often the very same copies as they read—and so the chain remains unbroken. Partly some remain enduringly popular for teaching purposes. And partly this is due to the very same trend of the ubiquity of contemporary cultural production: multimedia interpretations of classics. The Jungle Book has spread far and wide courtesy of Disney, Lord of the Rings by the Hollywood machine and Peter Jackson, the Narnia books by the BBC and others, Peter Rabbit by app designers—all of these new platforms have provided access to new generations of children, often leading them and their parents back to the original. And so Jon Stewart can name-check Beetlejuice, the Muppets, Tinkerbell, and Han Solo, knowing these will be recognized, and thus knowing the audience will understand his message: the childish nature of those he is satirizing.

So why have some previously extremely popular “classics,” like a few on Henrietta’s list, completely disappeared? What are the fashions which have expanded certain books’ appeal but left others languishing? There is no answer to this question but the whims of publishers and markets, which is precisely why the NYRB Children’s Collection has found a niche, and precisely why there are constant suggestions, endorsements, and introductions for the series.

On Difficulty

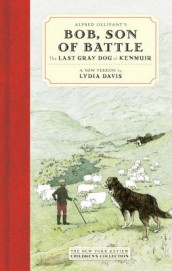

Lydia Davis has gone even further, and “translated” an old love of hers, Bob, Son of Battle, from English to English—that is, from a dialect of north England (with some Scottish) to a modern English stamped with her trademark clarity, sometimes even adding explanatory phrases. I suppose the original, by Alfred Ollivant, is deemed too difficult for children now, but I do wonder if this was checked. Ordering an original online was easy, and reading it was a joy. Its language is rich and evocative throughout, and so Davis’s re-wording cannot and does not retain what is special about the book; in fact, the translation has made something extraordinary into something rather ordinary, if more “accessible.” The first paragraph alerts a comparative reader, where “Relics of the time of raids, it looked” becomes “left from the time of the Scottish raids”; “a goodly array of dark-thatched ricks” becomes “a crowd of dark-thatched haystacks.” Later: “And the parson, striding away down the hill, was uneasily conscious that with him was not the victory,” becomes “. . . was uneasily aware that he had not won this battle.” The richness and the musicality have been lost for the sake of clarity, a feature which shows even more in speech; the characters are all rather flattened in the treatment (a common problem in translation). In speech, “ye” and “aye” have been kept all through for all characters, and this gesture to the dialect, while at the same time stripping it bare, rings false, as many gestures to dialect can. For why do they say “ye” and yet not “ain’t” (a word also familiar to a modern child)? Reading the original is undoubtedly a challenge, but children are obviously used to encountering words and ideas they do not know, for that is the nature of learning to talk and read.

Lydia Davis has gone even further, and “translated” an old love of hers, Bob, Son of Battle, from English to English—that is, from a dialect of north England (with some Scottish) to a modern English stamped with her trademark clarity, sometimes even adding explanatory phrases. I suppose the original, by Alfred Ollivant, is deemed too difficult for children now, but I do wonder if this was checked. Ordering an original online was easy, and reading it was a joy. Its language is rich and evocative throughout, and so Davis’s re-wording cannot and does not retain what is special about the book; in fact, the translation has made something extraordinary into something rather ordinary, if more “accessible.” The first paragraph alerts a comparative reader, where “Relics of the time of raids, it looked” becomes “left from the time of the Scottish raids”; “a goodly array of dark-thatched ricks” becomes “a crowd of dark-thatched haystacks.” Later: “And the parson, striding away down the hill, was uneasily conscious that with him was not the victory,” becomes “. . . was uneasily aware that he had not won this battle.” The richness and the musicality have been lost for the sake of clarity, a feature which shows even more in speech; the characters are all rather flattened in the treatment (a common problem in translation). In speech, “ye” and “aye” have been kept all through for all characters, and this gesture to the dialect, while at the same time stripping it bare, rings false, as many gestures to dialect can. For why do they say “ye” and yet not “ain’t” (a word also familiar to a modern child)? Reading the original is undoubtedly a challenge, but children are obviously used to encountering words and ideas they do not know, for that is the nature of learning to talk and read.

Diana Wynne Jones, veteran author for a range of ages (another suggestion for the series, as a few of her wonderful books have dropped out of print), had no truck with the assumptions of her readers’ capabilities. An adult once approached her at a signing event, and told her that the latest book was too “difficult.” Wynne-Jones turned to the child in tow. “And what did you think?” she enquired. “Brilliant,” he replied. She didn’t feel any further response was necessary. Her explanation, indeed a theme that runs throughout her essays, is that children are not stupid, and moreover they are generally more careful readers, bringing none of the assumptions that might lead adults to miss subtleties.

Language Play

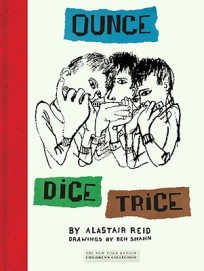

Fortunately, other books in the series delight in introducing new language and even making it up. Alastair Reid’s Ounce Dice Trice exhorts every child “to love words for their own sake” and to create words when the situation demands. “Words have a sound and shape, in addition to their meanings,” he says in the introduction. “Sometimes the sound is the meaning. . . . All the words here are meant to be said aloud, over and over, for your own delight.”

Fortunately, other books in the series delight in introducing new language and even making it up. Alastair Reid’s Ounce Dice Trice exhorts every child “to love words for their own sake” and to create words when the situation demands. “Words have a sound and shape, in addition to their meanings,” he says in the introduction. “Sometimes the sound is the meaning. . . . All the words here are meant to be said aloud, over and over, for your own delight.”

But there are also books for older children which simply do not make as much fuss over difficulty, which Diana Wynne Jones would applaud. Thurber’s The 13 Clocks had me running to a dictionary, even after I’d manage to unscrabble the word in a limerick. The book is a quite brilliant (sub)version of a fairy tale: a Prince disguised as a minstrel tries to win the hand—the only warm hand in the castle—of the Princess, niece of the ever-cold evil Duke, in the face of impossible quests and challenges, against a backdrop of a curse with the inevitable loophole (slyly nodded to: “‘In spells of this sort,’ Hark said, chewing, ‘one always finds a chink or loophole, by means of which the right and perfect prince can win her hand in spite of any task you set him.’”). There is all the logic of Alice in Wonderland: “‘Now let me see,’ the Golux said. ‘If you can touch the clocks and never start them, then you can start the clocks and never touch them. That’s logic, as I know and use it.’” The wordplay is in the best of the nonsense tradition, as seen in the aforementioned limerick, designed to make a woman laugh until she cried:

There once was a coddle so molly

He talked in a glot that was poly,

His gaws were so gew

That his laps became dew,

And he ate only pops that were lolly

Here are scrambled words and phrases from mollycoddle to polyglot—the one I didn’t know was “dewlaps” (a fold of loose skin hanging from the neck or throat of an animal, in case you didn’t either). You will have to read it to find out whether she did indeed laugh-unto-tears, and in so doing giving the prince one solution to his impossible tasks.

Fantasy routinely invents whole vocabularies when magic or other species require (in the most extreme cases whole languages are devised, such as for The Lord of the Rings, though not as far as I can recall in any of the books in this series—yet). The lizards in Lizard Music by Daniel Pinkwater have their own language, but in this case it’s largely untranslatable; luckily some speak English. In John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk and the follow-up The Box of Delights the sinister word “scrobble” is never defined, which adds to the sense of threat and fear and also mystery: what have the black-hearted villains done to brave Maria or the kind Bishop when they were “scrobbled?” And how do they get un-scrobbled? (This has now entered the dictionary, or at least the wiktionary and urban dictionary, with the primary etymology given: John Masefield, 1927. Neil Gaiman uses it in Neverwhere, with full acknowledgement.)

Fantasy routinely invents whole vocabularies when magic or other species require (in the most extreme cases whole languages are devised, such as for The Lord of the Rings, though not as far as I can recall in any of the books in this series—yet). The lizards in Lizard Music by Daniel Pinkwater have their own language, but in this case it’s largely untranslatable; luckily some speak English. In John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk and the follow-up The Box of Delights the sinister word “scrobble” is never defined, which adds to the sense of threat and fear and also mystery: what have the black-hearted villains done to brave Maria or the kind Bishop when they were “scrobbled?” And how do they get un-scrobbled? (This has now entered the dictionary, or at least the wiktionary and urban dictionary, with the primary etymology given: John Masefield, 1927. Neil Gaiman uses it in Neverwhere, with full acknowledgement.)

For Adults, for Children

And of course this playfulness in language isn’t restricted to children’s literature. Russell Hoban is an author who makes an appearance in both the NYRB Children’s and Classics series. The picture book The Sorely Trying Day is as lovely as the still-popular Frances books created by Russell and his wife Lillian. A father returns to the mayhem of four arguing children and a cat and a dog, with excuses being passed from one to another until the cat blames a mouse for distracting him, whereupon the mouse does the unexpected—he takes the blame, and apologizes. The cat is so taken aback he leaves the mouse to apologize to the dog, and so it goes on, until the children are all contrite and the parents appeased (with one more twist I won’t reveal).

And of course this playfulness in language isn’t restricted to children’s literature. Russell Hoban is an author who makes an appearance in both the NYRB Children’s and Classics series. The picture book The Sorely Trying Day is as lovely as the still-popular Frances books created by Russell and his wife Lillian. A father returns to the mayhem of four arguing children and a cat and a dog, with excuses being passed from one to another until the cat blames a mouse for distracting him, whereupon the mouse does the unexpected—he takes the blame, and apologizes. The cat is so taken aback he leaves the mouse to apologize to the dog, and so it goes on, until the children are all contrite and the parents appeased (with one more twist I won’t reveal).

Hoban’s contribution to the adult series, Turtle Diary, is my biggest literary find of the year, bar none. A haunting tale of two lonely adults, written from both perspectives in alternating chapters just a page or two long, Turtle Diary seems to be firmly in another tradition than A Sorely Trying Day, but close reading yields overlaps beyond the presence of animals; the internal thoughts of both protagonists in Turtle Diary have the whimsy of Hoban’s children’s books in both imagery and language play, such as when William G is eavesdropping on two oyster catchers at the zoo:

‘Kleep it and have klept with it for God’s sake,’ said one.

‘I don’t have to kleep it just because you klawp I should,’ said the other.

‘Then don’t kleep it,’ said the first. ‘It’s no klank off my klonk.”

‘Oh aye,’ said the second one. ‘You klawp that now but that’s not what you klawped a little klink ago.’

‘I klick very klenk what I klawped a little klink ago,’ said the first one. ‘I klawped either kleep it or don’t kleep it but stop klawping about it. That’s what I klawped.’

‘It’s all very klenk for you to klawp “Kleep it,”’ said the second one. ‘You’re not the one that has to kleggy back the kwonk.’

Frances the badger often resorts to making up words to express herself through her songs, and so Hoban had practice in expanding his range in this way—and it works, for all ages, as the above passage shows so well.

There is another double appearance in both the Children’s and Classics series—this one not only by the same author but the very same book. Pinocchio first appeared in the NYRB series packaged for adults in a slim, elegant, brown edition, introduced by Umberto Eco and with an afterword by Rebecca West, then reappeared three years later in a gloriously large, colorful, glossy version for children, with an introduction cut down from the adult’s version and without the afterword. (Foreign language books are another source for the series as they bypass a problem of rights; if a new translation is commissioned, the rights belong to the translation rather than the original. Thus the series is able to include Pinocchio, in a new translation by Geoffrey Brock, despite the many others available.) Each and every word is identical, but the materiality and aesthetics of the two versions couldn’t be more different. The illustrations—big, flat, bright, and crude—serve either to soften or increase the sense of danger at different points, or to highlight the humor or love in a situation, or to show the sinister side of characters which Pinocchio himself never spots in time. The Classics version has no illustrations, but the words alone serve in building the same anxiety, and the format is easier to handle; the big version is designed for poring over on a bed or floor, as children are wont to do.

There is another double appearance in both the Children’s and Classics series—this one not only by the same author but the very same book. Pinocchio first appeared in the NYRB series packaged for adults in a slim, elegant, brown edition, introduced by Umberto Eco and with an afterword by Rebecca West, then reappeared three years later in a gloriously large, colorful, glossy version for children, with an introduction cut down from the adult’s version and without the afterword. (Foreign language books are another source for the series as they bypass a problem of rights; if a new translation is commissioned, the rights belong to the translation rather than the original. Thus the series is able to include Pinocchio, in a new translation by Geoffrey Brock, despite the many others available.) Each and every word is identical, but the materiality and aesthetics of the two versions couldn’t be more different. The illustrations—big, flat, bright, and crude—serve either to soften or increase the sense of danger at different points, or to highlight the humor or love in a situation, or to show the sinister side of characters which Pinocchio himself never spots in time. The Classics version has no illustrations, but the words alone serve in building the same anxiety, and the format is easier to handle; the big version is designed for poring over on a bed or floor, as children are wont to do.

Another curious bridge between the two series comes with mythologies. In the Children’s series appear the classic D’Aulaires retellings of the Norse myths (and also the spin-off Book of Trolls, which takes the Norse folklore and runs with it). In the Classics series, labeled as being for young adults, are Rex Warner’s versions of the Greek myths and legends. Another interesting boundary category: mythology is indeed for everyone.

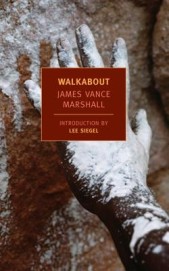

The slippage between writing for adults or children is also evident in books which have migrated from a Children’s classification when they were published to the adult’s Classics series. The very welcome addition Red Shift, by Alan Garner, centers on an adolescent relationship and as such no longer counts as for children. The same migration has happened to Walkabout, the story of a journey of three children, two white survivors of a plane crash in the Australian outback and one Aboriginal who saves them from the harsh environment they find themselves in. It is a difficult theme, with death a major feature and uncertainty and threat and fear pervasive, and also in the difficulties of shifting friendships and trust. But an adult book? Perhaps a red spine would not do its serious tone justice (it looks very good in its Classics design), and this is where perhaps the beauty of both series fails young readers: any content which shades into adult concerns, whether sex, death or violence, is excluded from their library.

The slippage between writing for adults or children is also evident in books which have migrated from a Children’s classification when they were published to the adult’s Classics series. The very welcome addition Red Shift, by Alan Garner, centers on an adolescent relationship and as such no longer counts as for children. The same migration has happened to Walkabout, the story of a journey of three children, two white survivors of a plane crash in the Australian outback and one Aboriginal who saves them from the harsh environment they find themselves in. It is a difficult theme, with death a major feature and uncertainty and threat and fear pervasive, and also in the difficulties of shifting friendships and trust. But an adult book? Perhaps a red spine would not do its serious tone justice (it looks very good in its Classics design), and this is where perhaps the beauty of both series fails young readers: any content which shades into adult concerns, whether sex, death or violence, is excluded from their library.

Making these distinctions between child and adult reading is to ignore the immense popularity among adults of new writing for children, epitomized by the Harry Potter phenomenon, a children’s book devoured by adults the world over. This phenomenon was repeated with the Hunger Games books, the Twilight series, and many more—all boosting the already biggest sector of the publishing market, that of Young Adult, or YA. Bloomsbury went as far as to publish an “adult” version of the Harry Potter books (that “could be read on the subway”) and captured the young and old YA audience – thus contributing to, even helping to shape, a new shared pool of cultural references, reinforced by movies, merchandise, games, apps, and other spin-offs.

Making these distinctions between child and adult reading is to ignore the immense popularity among adults of new writing for children, epitomized by the Harry Potter phenomenon, a children’s book devoured by adults the world over. This phenomenon was repeated with the Hunger Games books, the Twilight series, and many more—all boosting the already biggest sector of the publishing market, that of Young Adult, or YA. Bloomsbury went as far as to publish an “adult” version of the Harry Potter books (that “could be read on the subway”) and captured the young and old YA audience – thus contributing to, even helping to shape, a new shared pool of cultural references, reinforced by movies, merchandise, games, apps, and other spin-offs.

The blurbs on the covers are a mixture of old praise and new, from their first appearance and their recent revivals, which tells of enduring appreciation. But a deeper look shows the changing place of writing for children; for example, there are pull quotes from “serious” journals such as the Times Literary Supplement, although this august “adult” journal now does not review children’s books at all. Children were taken more seriously by authors, publishers, and reviewers than they are now, it would seem, with New York Review Books offering a notable exception: with this series they are showing trust and faith in children and their capabilities. The books, in all their difficulty, strangeness, humor, language, and unfamiliarity, are presented in beautiful editions. Children can be the best readers, and here they are given the best to read.