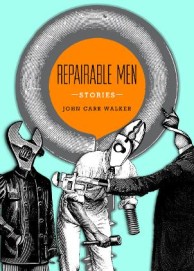

John Carr Walker

John Carr Walker

SunnyOutside ($13)

by Beth Taylor

In this first collection of short stories, John Carr Walker studies the psyches and stumbles of men in the rural west as they try hard to negotiate the mysteries of others and themselves. Whether it’s in a vineyard, the woods, or a hand-built house, his men respond crudely, trying to “repair” the damage in their relationships.

Animals pervade these stories—as victims, tools, and metaphors. In “Turning Over,” a husband’s care for a rabbit correlates with a turning point in his struggling marriage. “Grandeur,” the most literary story, parodies Kafka’s Metamorphosis as a man tracks birds dying from West Nile virus, investing himself so deeply into his subjects that he becomes one. In “Ain’t It Pretty,” an indecisive man invites his brother to his home in the woods, ostensibly to kill the annoying dog left by their recently deceased mother. But the visit resurrects the competition of their childhood, the legacy of their father’s harsh discipline, and the violence that has led the man’s wife to leave with their child. “Pups” continues the study as a wife neglects her husband’s wolf cubs in vague retaliation for whatever it is he can’t offer her.

Public history collides with private life in some of the stories, such as “A Sword from My Country,” in which an adopted Vietnamese teenager evokes a veteran’s memory of his “Orchid” during the war and the teen’s mother worries about what men do to pretty girls. Similarly, “Candelario” brings alive the complex nuances of racism and classism as the sons of a vineyard owner exploit their authority over experienced laborers, the callowness of youth leading to an education in guilt.

Father-son dynamics are, in fact, integral to many of these stories. In “The Atlas Show,” a father and son live a life of delusion, believing that each has been, or will be, an athlete of note, conning their ways toward impractical fantasies that at least bind them together in mutual appreciation. The strongest story is “The Rules,” in which a father and son clear a tree from a dirt road in a snow storm, risking their lives, and note that they are the only ones still following the rules of a back-to-the land dream, even though it had been the wife’s fantasy and she left long ago, returning to civilization.

Walker has a superb ear for dialogue, making each of these stories seem like a scene overheard—real people trying to translate others’ intensions, needs, and frustrations. It isn’t pretty, but Walker’s vision illustrates how hard it is to fix the messes of anyone’s life.