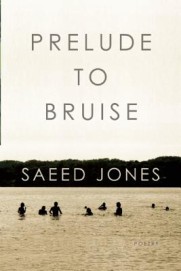

Saeed Jones

Coffee House Press ($16)

by Kate Schapira

With fire and ash in all senses, Prelude to Bruise shows how for a gay Black boy becoming a gay Black man, the danger of wanting and being wanted burns into wanting danger:

Singed, then smoked out: I'm your black matador, blood only

makes me readier.

These poems are thick with textures, acrid with smoke, phrases turned ever tighter:

These poems are thick with textures, acrid with smoke, phrases turned ever tighter:

. . . dream-headed

with my corset still on, stays

slightly less tight, bones against

bones, broken glass on the floor,

dance steps for a waltz

with no partner. Father in my room

looking for more sissy clothes

to burn. Something pink in his fist,

negligee, lace, fishnet, whore.

They are also rooted in a story. It's a story of the forces of destruction—the destruction of black bodies and black selves—built into America, and it surfaces in lines of lust, violence, possession, and power:

Want more, black moor, unmoored, loosed. Limp wrist, broke

wrist, rag doll, thrown. Backseat, head down, headlights, off.

and in lines of compromised love:

I survived on mouthfuls of hyacinth.

My hunger did not apologize.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

One fogged

night to the next, my palmpressed against each thrust.

How else to say moreplease under the sweat

and heave of their bodies?

Prelude to Bruise is also a story of escape from collusion with those forces of destruction, especially in its long late section "History, according to Boy," with its invocation of the power of turning away. Sometimes the story of escape morphs into myth, as with "Boy Found inside a Wolf":

I'm climbing

out of my father. His love a wet shineall over me. He knew I would come

to this: one small fistpunching a hole

to daylight.

Myth, here, is a tool to assert the depth and duration of a reality. The poems in Prelude to Bruise enflame, with all flame's consequences of wounding and illumination, but they do not surprise; anyone to whom this story is news has not been listening. The forms they take are considered, deft and purposeful, not inventive. Their phrases are vivid, moving, immersive, not startling. What's important about this story is not that it is new, but that it is old, both current and recurrent, and that its inflictions, discoveries, flares of light and sweet-bitter darknesses have been igniting in American bodies and spirits and feelings and actions. These poems insist on the long and present smolder of the story that gave birth to them. They call down animals and elements to witness it:

A grown man called boy

gone inside himself,the circle of wolves blinking gold

just beyond the trees.I am not a boy. I am not

your boy. I am not.

They wish to be heard not just by people to whom they're news but by the wind and the night, by the disaster and the morning after, and by all those to whom the story is burningly familiar.