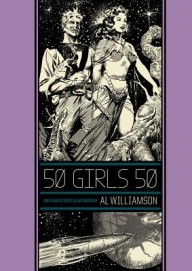

“50 Girls 50” and Other Stories

Illustrated by Al Williamson

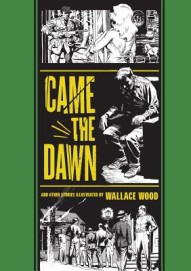

“Came the Dawn” and Other Stories

Illustrated by Wallace Wood

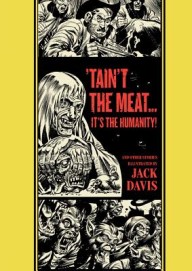

“’Taint the Meat . . . It’s the Humanity!” and Other Stories

Illustrated by Jack Davis

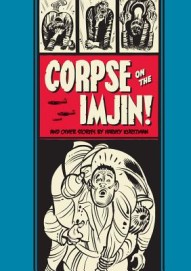

“Corpse On the Imjin!” and Other Stories

Illustrated by Harvey Kurtzman

by Paul Buhle

The Age of Anxiety—the period from the mid-1940s to the 1950s during which World War 3 was on everyone’s mind— has never been captured better than in the line of comic books known as EC (“Educational Comics” changed to “Entertaining Comics” and then shortened to the initials) published during that time. Late 1940s noir films tried, but the half-dozen lines of EC comics that came toward the end of the comic-book boom and just before a virulent censorship landed its first blows offered the best narratives, the most meticulous art, and the most amazingly progressive social values that mainstream comics had experienced. In a post-war America that had lost the unity and spirit of wartime, these stories were downright subversive.

Only today are we getting a thorough look at the artwork. Like baseball cards, comics have long had their hoarders. They preserve their commodities in plastic, file them away, treasure the odd item, and perhaps contemplate the Big Score of something purchased for pennies and sold for thousands of dollars. In the 1970s, collecting and a growing interest in the history of comic art led to a widening field of book reprints, at first in low-priced paperbacks and then in pricier versions. These days, it is easy to find even banal comics from the middle 1940s in reprint editions.

EC reprints are a different matter. From the mid-1980s, when four volumes of Mad Comics (1950-54) reappeared in hardbacks—including interviews with some of the creators—a due respect has been obvious. The fan-scholarly volume Tales of Terror! (2000), a heavily annotated catalogue of EC productions with more interviews, set the tone in another way. For a large handful of readers, these offered the best comic art ever, at least ever published in the U.S.

EC reprints are a different matter. From the mid-1980s, when four volumes of Mad Comics (1950-54) reappeared in hardbacks—including interviews with some of the creators—a due respect has been obvious. The fan-scholarly volume Tales of Terror! (2000), a heavily annotated catalogue of EC productions with more interviews, set the tone in another way. For a large handful of readers, these offered the best comic art ever, at least ever published in the U.S.

In the last half-dozen years, mini-biographies of several key EC artists, with samples of their work, have added to this recovery, bridging the gap between a devoted fandom and something like academia. B. Krigstein (Fantagraphics, 2002), Against the Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood (TwoMorrows, 2003) and The Art of Harvey Kurtzman (Abrams, 2009) presumably whetted the tastes for more reprints of EC originals.

And here are the first four volumes of an “EC Library” excavating a treasure trove of those originals. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to say in words alone how much this EC material means in comic art history, but these books will convince most readers of their significance. The semi-scholarly structure of the introductions is enhanced by afterwords, short bits of writing that range from memoir pieces of old-time fans to short biographies of the remembered and the forgotten. Noted jazz critic Ted White—a member of the early EC Fan Clubs, the small circles of devotees known for their scorn toward commercialized American culture—adds his bit to each volume, commentaries mostly in the range of who-hired (or fired)—who, at what moment some particular EC series rose and fell, why comics themselves rose and fell, and so on. The gossipy quality will appeal to many readers. Kurtzman’s volume has more added matter, including an essay and color reprints of the war comics covers that stand up as realistic antiwar classics, in effect so different from the celebration of conflict typical of other war comics. Kurtzman, the founding genius of the Mad enterprise and arguably the most influential editor at EC, also has two interviews, from 1979 and 1982, reprinted here.

The art itself in these four volumes, though it loses something in black and white, is the real stunner. Take “Corpse on the Imjin!” named for a story that is regarded as among Kurtzman’s best. It apparently grew, as many of his other comic tales, out of a Korean War GI’s own recollection, usually delivered in letters to Kurtzman from his faithful readers. Other stories here put on display his fanatical pursuit of details in war history, from the sixteenth century conquest of Mexico to the Civil War and World War I. His best tales are often narrated by a single soldier, the protagonist’s grasp limited by the danger in front of him, with his main hope being to get out alive. Not so much the blood and guts of battle here—although Kurtzman had a wonderful ear for sound and the unique talent for putting it into words—as the psychological state of warriors, the terrors and recurring sense of futility they experience. Remembered as a genius editor, Kurtzman would modestly change the subject when asked about his own comic art.

The art itself in these four volumes, though it loses something in black and white, is the real stunner. Take “Corpse on the Imjin!” named for a story that is regarded as among Kurtzman’s best. It apparently grew, as many of his other comic tales, out of a Korean War GI’s own recollection, usually delivered in letters to Kurtzman from his faithful readers. Other stories here put on display his fanatical pursuit of details in war history, from the sixteenth century conquest of Mexico to the Civil War and World War I. His best tales are often narrated by a single soldier, the protagonist’s grasp limited by the danger in front of him, with his main hope being to get out alive. Not so much the blood and guts of battle here—although Kurtzman had a wonderful ear for sound and the unique talent for putting it into words—as the psychological state of warriors, the terrors and recurring sense of futility they experience. Remembered as a genius editor, Kurtzman would modestly change the subject when asked about his own comic art.

For many of the other, younger artists, EC became a place to unleash energies and crypto-politics of resistance against the climate of McCarthyism. Today’s readers will be amazed by the anti-Semites, racists, and assorted rednecks exposed as Americana in Wallace Wood’s “Shock Suspense Stories.” A bohemian, leftish folksong devotee, Wood probably never joined any political group in his life, but his critique of the self-proud post-war American public reached the edge of McCarthy Era acceptability and sometimes went way beyond. Wood was at least as famous for his curvy dames and (in Mad Comics not seen here) his capacity for satirizing mainstream comic genres. A depressive in a depressing time, he drank himself to death, but his art is brilliant. If anyone still thinks that comics were never more than time-wasters for escapist children, they will learn better here.

Jack Davis, the only one of these artists still living (he is hale and hearty in his nineties) was another of EC publisher Bill Gaines’ favorites, and for good reasons. Apart from his fabulous satires in issues of Mad, Davis was a master in the horror comic Crypt of Terror line. Typically, the stories’ locals, parents to average citizens, refuse to believe in the supernatural—until the surprise ending where all is revealed. Davis went on to mainstream success, with thirty years at Mad Magazine, public interest posters, and an armful of awards. Even so, the screaming lady who experiences unimaginable horror as her respectability and life drain away will always remain his signature.

Jack Davis, the only one of these artists still living (he is hale and hearty in his nineties) was another of EC publisher Bill Gaines’ favorites, and for good reasons. Apart from his fabulous satires in issues of Mad, Davis was a master in the horror comic Crypt of Terror line. Typically, the stories’ locals, parents to average citizens, refuse to believe in the supernatural—until the surprise ending where all is revealed. Davis went on to mainstream success, with thirty years at Mad Magazine, public interest posters, and an armful of awards. Even so, the screaming lady who experiences unimaginable horror as her respectability and life drain away will always remain his signature.

Some close readers with a taste for crypto-politics (in Davis’ work, the crypt itself is never far away) may find some other qualities. Respectability is certainly on trial here. So is the feigned romance that hides potentially murderous materialistic craving. And the damned locale that pulls down everyone and everything. Perhaps the nearness of battlefield memories, or the re-emergence of the well-healed cocktail society unreformed, almost unaffected, by Depression and war, made this façade of civilization easy to tear down. Werewolves, very much in today’s television and evidently standing for something else, seem in Davis’ work a mere prop, but an awfully well-drawn, scary prop—at least for the cohort of EC Comics readers, reputed to be on average a few years older than enthusiasts of Batman and Donald Duck. This is gloom that the young and disillusioned grasped with delight or perhaps satisfaction. The national self-celebration of American society at mid-century was a fraud and with a little encouragement, practically anyone could see through it.

Al Williamson, described in the introduction to his volume as “an oddball among a collection of oddballs,” is the most old-fashioned of these four great artists. He loved adventure, with impossibly beautiful women and virile men, musculature and erotically taut flesh on display. He was perfect for the EC sci-fi series, perhaps because the extremity of surviving outer space and planets with weird monsters put these perfect human specimens on display. But there’s something else: some of the most telling EC stories of this kind are not set in outer space at all, but in humanity’s struggle for survival in the aftermath of atomic war. The old prophet of the survivors, centuries later, in one tale, warns that machines must never be rebuilt—but they worship the wheel! In another story two-eyed people are freaks, pursued violently by reptilian successors to radiation poisoning. And so on. In another decade, Williamson was one of the country’s most highly regarded illustrators. But the marvelous pathos of the EC days had vanished. Ray Bradbury—whose fiction was given visual form by Al Williamson in “A Sound of Thunder,” a sci-fi safari gone wrong—would never get a comic adaptation this good again.

Al Williamson, described in the introduction to his volume as “an oddball among a collection of oddballs,” is the most old-fashioned of these four great artists. He loved adventure, with impossibly beautiful women and virile men, musculature and erotically taut flesh on display. He was perfect for the EC sci-fi series, perhaps because the extremity of surviving outer space and planets with weird monsters put these perfect human specimens on display. But there’s something else: some of the most telling EC stories of this kind are not set in outer space at all, but in humanity’s struggle for survival in the aftermath of atomic war. The old prophet of the survivors, centuries later, in one tale, warns that machines must never be rebuilt—but they worship the wheel! In another story two-eyed people are freaks, pursued violently by reptilian successors to radiation poisoning. And so on. In another decade, Williamson was one of the country’s most highly regarded illustrators. But the marvelous pathos of the EC days had vanished. Ray Bradbury—whose fiction was given visual form by Al Williamson in “A Sound of Thunder,” a sci-fi safari gone wrong—would never get a comic adaptation this good again.

What society lost with the end of the EC comic lines can hardly be grasped today. Congressional hearings led by Senator Estes Kefauver in 1954 set out to “expose” the corruption of American children by comic books; when EC’s publisher William M. Gaines was called to the stand as the first hostile witness and dragged across the coals for mostly imagined sins, the titans of a then-vibrant comics industry hit the panic button, and resolved to police themselves with a new “comics code.” EC and Classics Illustrated alone resisted, but EC nearly collapsed, re-emerging with exactly one publication: the black and white Mad Magazine, not a comic and thus free from code restrictions. The idea was to reach younger kids and the result was slight, in volume and in sharpness, compared to the days of EC glory.

The youngsters who became the artists and enthusiasts of “underground comix” beginning in the late ’60s retained a lifetime resistance against comic book censorship, and a taste for radical art in other ways. Among the Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton et. al., crowd, however, “action” artists were few—Spain Rodriguez was perhaps the singular disciple of the EC style—and so the link in the chain leading back to EC had been broken, never to be restored.

The appearance of the EC Library with these volumes and more to come offers, then, an extraordinary opportunity for readers to delve comic art history, and enjoy the real golden age of comics all over again. The art, the scripts, but above all the collective talent on display here will reward many close readings.