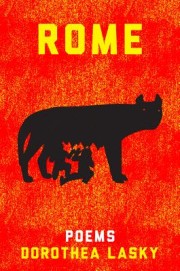

Dorothea Lasky

Dorothea Lasky

Liveright ($23.95)

by Gretchen Marquette

Dorothea Lasky’s fourth full-length collection, Rome, thrums with intelligence and uneasy energy. Within the first few pages it becomes clear that we’re in the presence of a speaker who will walk the razor’s edge between edgy and agitated, between vivacious and anxious. It’s difficult to pin this voice down. At times it’s careful and tender, as in her fantastic piece, “The Roman Poets,” and in this earlier poem, “You Were So Blond”:

Your skin was so soft and young

I forgot about having a baby

Or painting my nails with eggcream

I went down to your place and thought about you in your thoughts

Your thoughts are not plain

At other times it’s difficult to decide if her irreverence is meant to shock us into new realizations, or if she’s bored by her own pain; the voice is often tongue-in-cheek, perhaps feigning boredom while at the same time eager to provoke a reaction, as in an early poem in the book, “Why Poetry Can Be Hard for Most People”:

Because life is no more important than eating

Or fucking

Or talking someone into fucking

Or talking someone into something

Lasky’s catalog of the world—her relationships, experiences, and possessions—is rich and detailed. While never opulent for opulence’s sake, one gets the sensation that if this book were an object, it would be something brightly colored, hard and enameled, like a set of impeccable acrylic finger nails (though it would probably cringe to hear itself compared to something so ornamental). This is a book about beauty, but not beauty in its usual forms. The poet repeatedly draws as close to the bone as she possibly can; in “A New Reality,” she writes:

But to think I will never smell your hair in the rain

Is something I cannot bearAll the facts and figures

All the mathematics of an entire generationAll the mathematics in ten layers of being

Will never equal my love for you

The speaker, though, seems incapable of moving past these hurts: “You my horrible star / I can’t help but run to you when you call for me.” At times her loneliness is palpable, as in the poem, “I Know There is Another World”:

Under the palm trees

I know he still waits for me

His blue-green arms outstretched

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I know my children and husband wait for me

In the other world

To give myself over once again

Counteracting this pain are poems in which the speaker demonstrates her own power, as she does in “I Just Hope I Can Sleep”:

I hope that when you spot me in a field of honey

You keep on walking, walking past the honey

And drown yourself in a body of water

No I hope that there is a body of water

Which makes sense to you

An ocean of your own making

Unfortunately, the aesthetic here works to keep the reader at a distance, one figured in the opening line of the book: “Their bloodlust is what made them different from me.” This focus—on difference, or alienation—pervades the work on a deep level. Readers who look for poetry to serve as a bridge between themselves and others—a way to counter the estrangement or alienation they feel—may have a difficult time finding a way in, because Lasky’s interest lies more in examining the gulf between us than in spanning it. This interest often reads as being born out of frustration, but at other times out of curiosity, which is expansive, interesting, and strange. Her poem “The Empty Coliseum” exhibits this sentiment well:

Now I am greying

In the middle of my own and personal library

What to do, was it all a menagerie

Even when I can speak no longer

I will make in full the anonymous I

Or I will make you in full the anonymous I

I will fill the poems with great pain

And then suck out the meat so that they are only

Shells with only the memory of meat

So that they are only the memory of blood

It’s ultimately admirable that Lasky makes the decision not to lighten the emotional timbre of Rome, which is almost overwhelming in its persistence, and wholly unapologetic. She chooses to end the collection with a six-page poem that reiterates the themes introduced in the opening pages of the books—a long poem that somehow we’re not too exhausted to take in, and that continues to acknowledge pain but also allows the speaker to access her center of power. This ultimately leaves us in a place where we can believe that although Lasky has written a coda, she will soon have more to say on the subject.