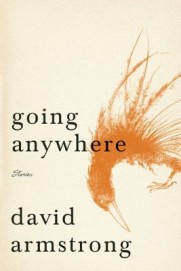

David Armstrong

David Armstrong

Leapfrog Press ($15.95)

by Isaac Faleschini

David Armstrong’s collection of short stories, Going Anywhere, promises much. Eight of the thirteen stories have won awards from reputable literary publications such as Mississippi Review, the Miriam Rodriguez Short Story Contest, and others. In addition, ten of the thirteen stories have been published in places as diverse as The Magazine of Science Fiction & Fantasy and New South. Happily, Armstrong’s prose, characters, and plots deliver on those promises.

The many and varied characters in this compilation bring important themes to life. Family dynamics are explored in many of the tales: the teenager in “Their Own Resolution” must deal with his father’s homosexuality; Clarence goes on an AA-like spree of forgiveness for those wronged in his past in “Straw Man”; Arthur in “Butterscotch” wrestles with the anxiety of becoming a father; and in “Courier” sixth-grader Eliman steps over his mother, who is naked and passed out on the kitchen floor, as his parent’s marriage dissolves.

It isn’t just the characters that keep the pages turning in this collection; the style and slow confidence with which Armstrong delivers his plot twists is exceptional. Does the overheated narrator in “Hear It” really hear the dog, Sheila, growl out the word spaghetti? In “Patience is a Fruit,” Jessie thinks he is seeing angels, but can the reader believe an angel darts its hand under the kettle of molten steel that he drops on his co-workers foot? Why does Barnabus’ dad pick him up after school with shotguns in the bed of the truck, “White price tags [hanging] from the stock of each one”?

Armstrong has a knack for rendering the mundane beautiful through lyrical language. Take this sentence from “A Different-Sized Us,” for example: “The well, a little bigger than a manhole, was shadowed by the canted lid from the morning light and looked cool and quiet near the crystalline blades of grass exposed to the sun.” He also processes emotion with deft realism. In “Bethesda,” the name of the magic pool where an angel’s touch heals the first person who plunges inside, a father and his crippled son wait, and the father’s anxiety is bare: “What if the minute I walk away, there it is, the brilliant white light over the water, because it could come . . . and you’re stuck there, and all the mattress-diving and all the planning doesn’t do us any good?”

Good stories promise a feeling that one is continuously being led on a journey, that anything can, and does, happen. Armstrong’s prose wriggles around narrative expectations, which in turn build toward deliberate payoffs. From “Take Care” to “Fifty,” the sensation in reading this book is that one could be “going anywhere.”