by James Naiden

She lived for just over sixty-three years (1912-1975), her last three decades as an active writer who published fifteen books in her lifetime, one posthumously. Born Dorothy Betty Coles on July 3, 1912 in the provincial city of Reading, she did not attend college or university. Her poor “Maths” skills in what we would call high school meant she was denied a certificate of graduation. So it was unlikely she would have acquired formal education beyond that. Instead, after working as a tutor, governess, and librarian, she met a young businessman when she was twenty-one at a theatrical production in which they were both cast. When they married in 1936, she took his surname.1

Taylor was respected as a writer during her lifetime but has been largely forgotten in the tumult of political and cultural upheavals within the generations since 1975. Her coincidental namesake, the London-born American film actress who was twenty years younger, appears to have had no effect on the writer herself, who remarked once—according to her husband—that when the actress got a good review, her own work was frequently praised as well. There was nothing to this claim, of course, meant in whimsical humor, but at least she was not deterred by an irrelevant consideration.

Virginia Woolf’s books were of singular influence on Taylor, if anyone’s were, but she did not engage in the normal effluvia of the literary life. She did not write book reviews or literary essays, nor did she attend literary gatherings. She and her spouse had two small children when she began what would be her first published novel, At Mrs. Lippincote’s, eventually appearing in the U. K. in September 1945. The book was brought out in the United States and Canada the following year, when the stresses of wartime shortages had abated. Her husband John was a successful, middlebrow owner of a sweets factory. He seems to have encouraged his spouse in her driven activity. Ray Russell, with whom Elizabeth had an early relationship, had been captured by the Germans during the Second World War. Her husband, while sympathetic to Russell’s earlier misfortunes, insisted that her affair with him “must end”—and so it did, although she did continue writing to him. 2

Virginia Woolf’s books were of singular influence on Taylor, if anyone’s were, but she did not engage in the normal effluvia of the literary life. She did not write book reviews or literary essays, nor did she attend literary gatherings. She and her spouse had two small children when she began what would be her first published novel, At Mrs. Lippincote’s, eventually appearing in the U. K. in September 1945. The book was brought out in the United States and Canada the following year, when the stresses of wartime shortages had abated. Her husband John was a successful, middlebrow owner of a sweets factory. He seems to have encouraged his spouse in her driven activity. Ray Russell, with whom Elizabeth had an early relationship, had been captured by the Germans during the Second World War. Her husband, while sympathetic to Russell’s earlier misfortunes, insisted that her affair with him “must end”—and so it did, although she did continue writing to him. 2

Her epistolary friendship with fellow novelist Robert Liddell (also a prominent literary critic until his death in 1992) shows that Taylor was not indifferent to the reactions of other writers to her work, including luminaries as Elizabeth Bowen and Ivy Compton-Burnett. Liddell would remain, as would others, a lifelong friend and supporter of Taylor’s work. Perhaps that he lived abroad in either Egypt or Greece (principally Athens) augmented Taylor’s early affinity for Greece and the Greek language, and fixed Liddell as a conduit to a place she had visited but had never stayed for long.3 But what shaped this unlikely candidate for literary exception?

After her formal schooling ended in 1930, she was employed in a succession of jobs—governess, tutor, and librarian, as well as a non-paying stint in amateur theatrical productions, as mentioned earlier. She said later she knew she would be a writer from the time of her adolescence, but because she was denied a university education, she knew it would not be easy. Reading books, with regular visits to the public library, was the one route she had to learn, aside from the drudge of sending work out only to have it rejected, sometimes summarily. Nicola Beauman documents Taylor’s methods and frustrations, laid out revealingly in her correspondence with Ray Russell before, during, and after his imprisonment in Austria. Earlier, by the time war had arrived—September 1, 1939—Taylor was busy with her family and trying desperately to finish a publishable novel. After her marriage, money worries were non-existent, not an inconsiderable factor in her creative output.

Taylor’s involvement in the Communist Party was not frivolous, and it seemed not to inject stress in her marriage. From the evidence known, John Taylor regarded his wife’s political views as possibly eccentric but harmless. She was a lifelong atheist, as well, and viewed extreme right-wing movements such as that led by Oswald Mosley in the 1930s in near-imitation of Hitler in Germany as an indication that action, not prayers, were the only way to defeat bilious and undesirable social/political antipathies. As for the Communist Party, it was the indigenous British version, hardly subversive, more concerned with conditions of the working class than Leninist agitation and revolt. Taylor’s eventual boredom with the local chapter in the first town she and her family lived is depicted convincingly in Taylor’s first book, At Mrs. Lippincote’s, which mirrored many aspects of the Taylors’ lives, including her faithless husband, although apparently it was not a source of declared tension. “The novel is humorous rather than comic,” Liddell wrote appreciatively, “and melancholy rather than sad, and yet entirely unsentimental”—as indeed a trademark of Taylor’s fiction would be for the rest of her career.4 Neither comedic impulse nor political tendentiousness interested her within her craft.

When it was suggested she might apply for formal membership in the Party, she retreated into measured diplomacy, polite but candid:

It is more or less an accident that I stumbled upon you all. There’s nothing in my experience to take such a step. I feel it would be an affectation, not altogether trustworthy. I don’t think you can understand. You’ve worked in factories all your life. I’ve never been inside one. I’ve been treated with consideration by everybody, never victimized . . . I’m lonely, like all my kind. The thing I notice about you all is that you’re never lonely. You get tired, you argue, quarrel even, but you all love one another and depend on one another and give one another courage. 5

Taylor was more fortunate than her character Eleanor, in that Taylor’s family assuaged some feelings of loneliness, as did her correspondence with Ray Russell and her subsequent friendship with Maud Eaton, a younger woman and native of New Zealand, who was passionately interested in literature.6 Taylor’s correspondence with Russell was still active but less intense after 1948, and she needed a female friendship outside of her domestic life, her life of writing and keeping house. Maud Eaton is a curious case, for she is portrayed in some ways as Camilla in A Wreath of Roses (1949), Taylor’s third novel. There are two suicides in the book, one at the beginning and another at the end. Coincidentally, after being caught by an ear infection—tinnitus—and having no cure for it, Maud Eaton took an overdose of sleeping pills. Taylor felt much chagrin, possibly even guilt, upon learning this.

By 1948, Taylor left the Communist Party. Russell was chagrined, but was apparently able to compartmentalize his disappointments once married. He and Taylor were in communication regularly until nearly the end of the 1940s, when she also started writing to Robert Liddell, by then living in Cairo and not long thereafter to depart for Athens. Taylor went on to support the Labour Party with various degrees of enthusiasm for the rest of her life. Taylor had no desire to give up the comfortable lifestyle her marriage afforded. Her children were growing up. Her son was at boarding school. She began to have more time and energy for her writing. Her novels had come out with regular frequency since 1945 and she began to publish short stories in American magazines, in particular The New Yorker and McCall’s. Her principal editors at the former were Katharine White and then William Maxwell, both supported in their judgments by editor-in-chief William Shawn, who also admired Taylor’s work.

Her second novel was Palladian, published in 1946. Memories of her pre-marriage experience as a governess/tutor were drawn upon dexterously in the composition of this book. The central character is Cassandra, who was eighteen and newly orphaned just as she finished her formal education. Again, Taylor’s penchant for the Greek language comes into play as Cassandra’s employer, the mysterious but attractive Marion Vanbrugh insists that Cassandra tutor his daughter, Sophy, in the language, perhaps so that she can read Pliny and Sappho and other austere immortals in the original. Cassandra agrees to this. With her knowledge of French and basic skills in arithmetic, she tutors and tries to guide Sophy into a constructive view of the world, which seems to backfire as the girl has developed singular eccentricities.

Among other characters, we see in this novel many men addicted to drink or at least not averse to it, who have escaped living with women but still like them for sex and companionship. Might Ray Russell have been a prototype for some of these sodden characters? He was an artist, too, but had no known dependency on booze. He did marry, as we have seen, relatively late at age thirty-nine, but his affection for Elizabeth, his early lover, never abated. In the decades-spanning missives between Taylor and Russell used in Beauman’s account, we see the novelist’s frustrations, her occasional pessimism, and her ebullience when a novel was finished as well as despair when a negative review might pop up. She also wrote of her approbation about her own abilities as a novelist when a positive review appeared or a letter of encouragement, even praise, from a fellow writer—such as Elizabeth Bowen, Elizabeth Jane Howard, Robert Liddell, or Graham Greene. The novel ends, after Sophy’s accidental death, when Marion proposes to Cassandra and she accepts him. Indeed, although it is unspoken at first, the reader is aware though Cassandra’s interior monologue that she believes falling in love with Marion “will do”—lest she become a spinster, a horrid thought. Although the author’s life trajectory was very different than Cassandra’s, as far as one can tell by novel’s end, it is a story spun out of real-life experience.

At one point, Marion, who is of independent means and owns the house, partially adorned with a Palladian façade (another echo of Taylor’s love for Grecian influences), gives Cassandra a Greek lesson and then takes her down to the cellar where his wine stock is kept. She opts for sherry when he asks, possibly because on Sundays, her parents had served roast beef, and sherry went with the meal:

There was nothing of roast beef in this sherry, Cassandra thought. It had no Sunday morning associations for her. It was essentially a drink for the violet hour, the cool summer airs, the earth reeling over into darkness and flowers stiffening their petals against the night; it was quiet in the mouth, like olives.

After only small sips, Cassandra’s perceptions are blurry. Marion perceives that she is slightly inebriated while Tom, encountering her in the upstairs hallway shortly afterward, insists she is “drunk.” Would a glass of sherry, harmless in itself, have this effect on one who seldom drank alcohol?

Her head was like a globe of shifting flakes; when she moved, it became full of confusion like the snowstorm in a glass paperweight.7

In 1947, A View of the Harbor appeared and received generally favorable reviews. It’s worth noting that Newby, a small town by the seaside in southeastern England, a fishing harbor, has its variable residents, including Beth Cazabon, a novelist, and Robert, her physician husband. There is a small myriad of others, such as the elderly and infirm Mrs. Bracey, her daughter Maisie, Bertram Hemingway, a retired sailor who has taken up painting seascapes and views of the harbor itself, Tory, a divorceé and carrying on an affair with her next-door neighbor, Dr. Cazabon, without Beth’s knowledge, and Prudence, their teenage daughter, courted by Geoffrey, the idealistic son of one of Beth’s old school chums. Geoffrey is also an admirer of Beth’s novels, although there is barely one serious conversation between Beth and her reader. Should we assume Taylor was writing about a younger version of herself?

In 1947, A View of the Harbor appeared and received generally favorable reviews. It’s worth noting that Newby, a small town by the seaside in southeastern England, a fishing harbor, has its variable residents, including Beth Cazabon, a novelist, and Robert, her physician husband. There is a small myriad of others, such as the elderly and infirm Mrs. Bracey, her daughter Maisie, Bertram Hemingway, a retired sailor who has taken up painting seascapes and views of the harbor itself, Tory, a divorceé and carrying on an affair with her next-door neighbor, Dr. Cazabon, without Beth’s knowledge, and Prudence, their teenage daughter, courted by Geoffrey, the idealistic son of one of Beth’s old school chums. Geoffrey is also an admirer of Beth’s novels, although there is barely one serious conversation between Beth and her reader. Should we assume Taylor was writing about a younger version of herself?

Newby, as Liddell points out in his afterward, is a modest train ride “up to London” for a day of shopping, perhaps. In Taylor’s novel, there is New Town, a cluster of post-war houses built up not far away, leaving the older port town to apparent desuetude. Still, you live where you live at any one time. Taylor’s characters both stay and leave by novel’s end. They also die, as Mrs. Bracey finally does, much to her daughter Maisie’s relief. They all gossip furiously, and love and hate. There is deception, of course, principally with Robert and Tory falling in love, much to Beth’s obliviousness but not to their daughter Prudence who discovers it, and then Bertram proposes more than once to Tory. Both he and the reader are surprised when she finally accepts him. By novel’s end, they are packing and ready to leave for a flat in London, near where Tory’s son Edward is in boarding school. Loneliness, as Liddell points out, is Taylor’s great theme, as well as the friendships of women. It is also notable that Taylor was exploring her own fragile balance—as a novelist and also a dutiful wife and mother.8

A Game of Hide and Seek was published in 1951, Taylor’s fourth novel. In 1950, the entire first chapter had been published in The New Yorker, a high compliment to Taylor’s work as well as her bank account. The author’s influences, her love of Greek, and her admiration for a teacher of Greek during her teenage years all enter into A Game of Hide and Seek as deftly as any novelist using the past as a conduit to self-understanding. It was far more than that, of course. Taylor’s narrative abilities to build terrible choices for her characters—Harriet’s love for her childhood crush versus her duty to her husband and young daughter–this oppositional pull is what drives the novel and why it is a salient book in her oeuvre. Taylor’s ability to describe much in concise imagery is remarkable. For example, three short sentences describe anguish, momentary though it is: “Terrible shrieks were coming out of the loud-speaker horn. Caroline put her hands to her ears. Harriet’s eyes were stars.” 9

A Game of Hide and Seek was published in 1951, Taylor’s fourth novel. In 1950, the entire first chapter had been published in The New Yorker, a high compliment to Taylor’s work as well as her bank account. The author’s influences, her love of Greek, and her admiration for a teacher of Greek during her teenage years all enter into A Game of Hide and Seek as deftly as any novelist using the past as a conduit to self-understanding. It was far more than that, of course. Taylor’s narrative abilities to build terrible choices for her characters—Harriet’s love for her childhood crush versus her duty to her husband and young daughter–this oppositional pull is what drives the novel and why it is a salient book in her oeuvre. Taylor’s ability to describe much in concise imagery is remarkable. For example, three short sentences describe anguish, momentary though it is: “Terrible shrieks were coming out of the loud-speaker horn. Caroline put her hands to her ears. Harriet’s eyes were stars.” 9

More than six decades later, one can see readily the conflicting points of view, but the quality of Taylor’s achievement is undeniable. The story presents high emotional conflict in Harriet’s life, and while there is no clear-cut resolution in the end, the author’s deft control over the fates of her characters, as both Liddell and Beauman point out, lifts the story well beyond the commonplace. Indeed, A Game of Hide and Seek would have to be considered among her best performances.

When The Sleeping Beauty was finished in the summer of 1952 and published the following year, Taylor was in a fine stride as a novelist. Although, as mentioned earlier, she rarely partook of literary confabs and never did any reviewing or essay writing, she did maintain a steady rhythm. The Sleeping Beauty involves a deception centered around Vinny10, supposedly a middle-aged bachelor, and the woman he loves, Emily, as well as her resentful sister, Rose, and of course Rita, who married Vinny years earlier when she claimed to be pregnant but was not, as it turned out. There is also Isabella, a recent widower whom Vinny pays attention to at first before he decides on Emily. Laurence is Isabella’s soldier son, who has a college education but has no further ambition than to be a farm laborer. (Whether this is a joke or not is not explained or demonstrated.) It is worth noting that Taylor uses her “neighborhood” in southeastern England repeatedly, as if mining for insights continuously. One writes best about what one knows. She is also capable of some exquisite imagery: “The sea, winking with light, was stretched taut like a piece of silk.”11 Such divertissements are not uncommon.

The Sleeping Beauty is a good example of a book’s reception both favorable and unfavorable. The bad reviews, as Beauman recounts, tended to haunt Taylor more than the good ones, even praise privately tendered by editors such as William Maxwell, which to some degree bolstered her confidence. When one editor suggested perhaps tactlessly that Taylor revise the book, she declined and eventually changed American book publishers.

The year 1954 saw Taylor’s first short-story collection, Hester Lilly, appear in the United States. The book comprises one novella (the title entry) and twelve short stories, some longer, some very short—one only three pages. The title novella is nearly ninety pages. Hester Lilly is a young woman whose parents have died, who has no siblings, and the only living relative is an older cousin, Robert, married to a woman his own age named Muriel. Although Beauman demonizes Muriel as scheming, if not worse, a more balanced assessment is that, failing to have children, her marriage to Robert, a schoolmaster in postwar England, is stultified. The sudden presence of a young, attractive cousin—Hester—threatens her relationship with her husband. Robert displays no amorous interest in Hester, only concern for her welfare and a desire to help, if possible. Hester’s story is familiar: a young woman suddenly alone in the world is a theme Taylor returned to often. Hester is just one more unmoored person in a basically harsh world in which predatory natures are always rampant. Of the story itself Robert Liddell wrote: “it is far richer in atmosphere and more profound in its study of human nature.”12 In the end, Hester meets Hugh Basenden, a young schoolteacher who has come to work at Robert’s school. After only a brief acquaintanceship, he asks Hester to marry him. Diffidently, she accepts him. The story is essentially over at that point. However, what is remarkable are not the human vis-á-vis human internecine battles or rivalries, suspicions at the very least, but Taylor’s observances of nature. This is where one gets a full appreciation of the author’s command of visual imagery:

The bark of the trees was blood-red in the dying light, and there were no sounds of birds of anything but branches creaking and tapping together. Then the pink light thinned, the trees opened out, and blueness broke through, and in this new light was a view of a tilted hillside with houses, and a train buffeting along through cornfields.13

Such descriptions are not uncommon in Taylor’s descriptions of human relationships. Taking one of the book’s short stories, “The First Death of Her Life,” one sees this deft, painterly quality in images both of what is happening kinetically and the unspoken essences poetry might capture. Taylor depicts a young woman whose mother has just died in hospital. Her father, presumably the deceased’s husband, is late. The world is late, it seems, but death will not be denied, and what may seem callous is indeed matter-of-fact:

The nurse came in. She took her patient’s wrist for a moment, replaced it, removed a jar of forced lilac from beside the bed as if this were no longer necessary, and went out again.14

In the immediacy of a loved one’s death, or any death, the world doesn’t stop, nor does Taylor imply that it should. Discordancies ring aplenty. As the young woman leaves the hospital, she is confronted by a half-expectation:

Opening the glass doors onto the snowy gardens, she thought it was like the end of a film. But no music rose up and engulfed her. Instead there was her father’s turning in at the gates. He propped his bicycle against the wall and began to run clumsily across the wet gravel.15

Because we are sentient beings, inadequacies seen by each person may be chafing. Taylor doesn’t dwell on this, but merely describes it, and as with her descriptions of nature, the poetry emerges.

In January 1956, Taylor began writing Angel—a story atypical in that the central character was not a contemporary. The character Angel Deverell was born to distressed, working-class parents in 1885 (Taylor, as noted above, was born in the summer of 1912). A single child, Angel is possessed by monomania, a hatred of anyone telling her what to do—that is, authority figures such as her mother or any of her teachers—and a single-minded intention to become a novelist, although peculiarly she doesn’t read that much, if anything, which might lend polish or veracity to her writing.16 Yet Angel, who sets out on her writing career still in her teens, refuses to attend school after a teacher suspects her of plagiarizing something she had indeed written. She instead spends her time in the flat above her mother’s shop on Volunteer Street, writing in her bedroom, much to her mother’s distress. As Beauman suggests by inference, this reverse doppelgänger was a stylistic but still quite viable technique, drawing upon one’s experiences and creating an opposite person with a ferocious appetite for both work and success. Taylor had that appetite in the extreme.

In January 1956, Taylor began writing Angel—a story atypical in that the central character was not a contemporary. The character Angel Deverell was born to distressed, working-class parents in 1885 (Taylor, as noted above, was born in the summer of 1912). A single child, Angel is possessed by monomania, a hatred of anyone telling her what to do—that is, authority figures such as her mother or any of her teachers—and a single-minded intention to become a novelist, although peculiarly she doesn’t read that much, if anything, which might lend polish or veracity to her writing.16 Yet Angel, who sets out on her writing career still in her teens, refuses to attend school after a teacher suspects her of plagiarizing something she had indeed written. She instead spends her time in the flat above her mother’s shop on Volunteer Street, writing in her bedroom, much to her mother’s distress. As Beauman suggests by inference, this reverse doppelgänger was a stylistic but still quite viable technique, drawing upon one’s experiences and creating an opposite person with a ferocious appetite for both work and success. Taylor had that appetite in the extreme.

Angel is likewise suited but without common courtesies or much interest in the day-to-day struggles of her peers, not the least of her own mother or her aunt Lottie, who mean well but are seen as tiresome and presumptuous. Angel eventually marries an opportunistic painter named Esmé, whose sister Nora lives with them in the once and future dilapidated old house in the country known as Paradise House, in real life a place Taylor knew existed but never actually saw.17 Angel’s husband dies in a lake accident, leaving her and her sister-in-law to grow old together. Angel dies in Nora’s arms—old, impoverished, forgotten as a writer, an example of true pathos, what every writer dreads. The mise-en-scéne is convincing, at least for the reader of the twenty-first century, albeit sans computer, Internet, or fax machine. Taylor herself did not face poverty, nor was she forgotten in her lifetime.

In 1958, the year she turned forty-six, Taylor saw her second short story collection published—The Blush and Other Stories. The volume had most of her hitherto ungathered stories since Hester Lilly four years earlier that had appeared among other journals over the years in The New Yorker, Taylor’s favorite place to have her work published. Validation was part of it, certainly, but so was the exposure of her work to the American readership, much wider and larger than in the U.K. Money also was a factor. No publication in English paid as much as The New Yorker. Politics may have played a minor factor in Taylor’s decisions about where to try and get her stories published. Indeed, the Labour government had long since vanished in the Conservative sweep of 1951. By now, in post-Churchillian England, Harold MacMillan was in power at Downing Street. While Taylor disapproved of Conservative policies, as much as she could bear to read or hear about them through the media, she kept her politics out of her work. “Put that in a novel,” she might have heard Norman Mailer contend, as he did so often, “and you’ll be sidelined as a writer. That’s not where I’m at.”

In 1958, the year she turned forty-six, Taylor saw her second short story collection published—The Blush and Other Stories. The volume had most of her hitherto ungathered stories since Hester Lilly four years earlier that had appeared among other journals over the years in The New Yorker, Taylor’s favorite place to have her work published. Validation was part of it, certainly, but so was the exposure of her work to the American readership, much wider and larger than in the U.K. Money also was a factor. No publication in English paid as much as The New Yorker. Politics may have played a minor factor in Taylor’s decisions about where to try and get her stories published. Indeed, the Labour government had long since vanished in the Conservative sweep of 1951. By now, in post-Churchillian England, Harold MacMillan was in power at Downing Street. While Taylor disapproved of Conservative policies, as much as she could bear to read or hear about them through the media, she kept her politics out of her work. “Put that in a novel,” she might have heard Norman Mailer contend, as he did so often, “and you’ll be sidelined as a writer. That’s not where I’m at.”

The Blush has twelve stories, not all with autobiographical derivations—is it possible always to detect this in a fiction writer’s output?—but certainly mnemonic elements providing considerable fictive amplitude. For example, the title story, one of the shortest in the book at only eight pages, reveals those who work for others and those who depend on hired help to run their own households, or think they do. Mrs. Allen, childless and edging into middle age, is helped with domestic chores by Mrs. Lacey, who has three children at home, fears she might be pregnant again and doesn’t feel well, not helped by occasional drinking bouts at The Horse and Jockey, a local tavern. She has a sober husband, remarkably, who has a suitable job (we never learn what it is, except that it is in a neighboring town) and earns enough money that his wife doesn’t need to work for another household. When Mrs. Lacey leaves early, leaving a note that she is ill, Mrs. Allen is distressed, for she is not used to doing laundry or tidying up. Still, Mrs. Allen bears up, not without compassion. That afternoon she is visited by Mr. Lacey. The two have never met before. He explains that his wife is pregnant (which Mrs. Allen already suspected), that she doesn’t need outside work because he makes good money, and that he hopes Mrs. Allen understands because his wife cannot say No. Mrs. Allen agrees immediately. After the man leaves, Mrs. Allen feels embarrassed, almost as if she were to blame for Mrs. Lacey’s physical ailments, which of course she has had no part in. Still, she feels some guilt:

Then she felt herself beginning to blush. She was glad that she was alone, for she could feel her face, her throat, even the tops of her arms burning, and she went over to a looking-glass and studied with great interest this strange phenomenon.18

Taylor’s friendship with Liddell bears mention again, for “The Letter-Writers” also appears in this book. Originally appearing in The New Yorker, it is a fictional chronicling of their first encounter. In fact, as Beauman recounts, he did not come to see her first in England. (The poet Leslie Yates, who died in 1943, was the inspiration for this story.) There was, however, a naturally exorcistic quality about it in regard to her correspondence with Liddell.19 Edmund visits Emily, who has prepared a meal of lobster. However, when she steps outside momentarily, her cat makes a mess of the lobster. Just as Emily is about to toss the cat out the front door, Edmund appears, taken aback but gracious, as she might have expected. He is slightly but not significantly “different” in person than what she’d expected, and they get on pleasantly. In the shifting of points of view back and forth, Taylor’s gifts are evident. Just before the visit, she allows us the predispositions of each letter-writer vis-à-vis the other:

At first, he thought her a novelist manqué, then he realized that letter-writing is an art by itself, a different kind of skill, though, perhaps with a different motive—and one at which Englishwomen have excelled. As she wrote, the landscape, flowers, children, cats and dogs, sprang to life memorably. He knew her neighbors and her relation to them, and also knew people, who were dead now, whom she had loved. He called them by their Christian names when he wrote to her and re-evoked them for her, so that, being allowed at last to mention them, she felt that they became light and free again in her mind, and not an intolerable suppression, as they had been for years.20

In a Summer Season, an accomplished novel by any standard, was published in 1961. In it Kate, a middle-aged woman, has remarried after her husband’s sudden death to Dermot, who is a decade younger. He has no money and is unemployed, whereas Kate does have money. Therein is part of the problem in their marriage, although she refuses to acknowledge it. In this novel, there is the flavor of upper middle-class life depicted through a series of unpredictable events. In 1982, the British critic Susannah Clapp contributed a salient forward to a new edition, writing, “Secrecy makes Kate’s intensities more insistent: so does a background which is both comfortable and sedate,” Clapp writes. “Elizabeth Taylor’s skill at catching the predictable and soothing in middle-class life, in pointing to its limitations without scorn, never deserted her.”21

The Soul of Kindness was printed in 1964. In contemporary American parlance, this book would have to be considered “edgy”—that is, fraught with competing egos, frustrated ambitions, the very best of intentions: all of this does not quite descend into tragedy, but catastrophe hovers closely. The central character, if there is one and so depicted as “the soul of kindness” is Flora, married to Richard, a straightforward businessman who prefers his life uncomplicated by suspicion and distrust as well as all other mortal shortcomings. Richard realizes this may be impractical, but Flora wants to do good by everyone she knows. Richard and Flora employ Mrs. Lodge, a housekeeper, who had announced her desire to leave their employment in order to return to the country, where she spent her earlier life. One finds Taylor’s depiction of these characters replete with color and emotion, qualities that make convincing fiction. The book is “one of her best novels,” judged Liddell some twenty years later. “There are scenes in variety, but connected by an interesting theme and one that she made particularly her own, the self-deceiver.” 22 In other respects, The Soul of Kindness can remind one of a soap opera, which perhaps it is to a certain extent.23 Flora’s determination to cement her marriage against any threat, real or imagined, as well as provide a healthy environment for their baby daughter are described in near-believable pathos:

As it was Mrs. Lodge’s day off, Flora had made a special dish for Richard’s dinner—his favourite steak pie. She had a feeling today she must propitiate him, draw him close with every gyve she could find. This particular gyve, the steak pie, she kept taking out of the oven, then putting it back. The pastry seemed to be hardening. She wandered about the house—went up to Alice several times: but as in the dream Alice slept peacefully, her legs on top of the light coverlet, her hair stuck to her head like damp feathers.24

A third collection of short fiction, A Dedicated Man and Other Stories, appeared in 1965. Twelve stories, all highly trenchant and evocative of English life both at home and in the experiences of traveling abroad, comprise this salutary book. The title story suits our purposes here. Silcox, a professional waiter in middle age, has Edith as a partner, although he treats her at times with contempt. Silcox’s verbal abusiveness toward Edith prompts her departure at story’s end. Taylor’s rendering pits the story well: Silcox has just been informed that Edith has gone:

Before the new couple arrived, Silcox prepared to leave. Since Edith’s departure, he had spoken to no one but his customers, to whom he was as stately as ever—almost devotional he seemed in his duties, bowed over chafing dish or bottle—almost as if his calling were sacred and he felt himself worthy of it. 25

Although 1967 and 1968 were significant years politically and socially around the world, especially in the United States, this was a period of quietude in Taylor’s life. She and her husband went on trips to North Africa as well as islands near Greece, though Taylor herself “boycotted” the country, as noted above, because of its military junta. She also completed work on Mossy Trotter, a book supposedly just for children. The nickname and surname of a eight-year-old boy, Robert Mossman Trotter, the novel is built of simple declarative sentences and the point of view is exclusively Mossy’s—dealing with his parents (especially his expectant mother), his younger sister Emma, and fears of ridicule at being dressed for a wedding as a “page boy” which he overcomes as he develops a fondness for Alison, the page girl, who has a tendency toward maladroitness and thereby inflicting minor injuries upon herself. That Mossy Trotter is written from the point of view and thus uncomplicated language of a third-grader helps considerably, for Taylor and her husband had raised two children of their own and grandparenthood was in the offing. Still remarkable, even stunning at times, are the observations reflecting both her characters and nature, the latter especially worth noting at the beginning of Chapter Seven:

The summer was now quite over. The cherry trees dropped their thin yellow leaves onto the grass, and the autumn flowers were out in the garden—Michaelmas daisies and goldenrod. Big striped spiders spun beautiful webs from stem to stem, and the hedges on the damp, misty mornings were covered with cobwebs.26

Elizabeth Taylor’s past came to visit her again as she labored on The Wedding Group, published in 1968. The setting is a disparate one. Quayne, a village of Catholic artists and sculptors, was where Taylor (as Betty Coles, before she met her future husband) lived briefly in the early 1930s. Pigott was its real name, and Eric Gill, the leader, was renamed Harry Bretton, a sculptor. Beauman speculates back and forth whether there might have been a sexual relationship in the wake of Elizabeth posing in the nude for Gill. At any rate, this novel—judged by some to be her weakest—does have problems with characterization. The character Midge is an excruciatingly lonely woman whose youngest son still remains at home, after a fashion. (The older two sons have married and live far away, and her husband has long since left her for a depressingly solitary existence of his own.) Taylor’s time at Pigott was brief, but she remembered the thin outlines of personalities some thirty-five years or more in the past, enough to craft an imperfect novel about disharmonious characters who never quite fuse with each other. Midge’s youngest son, David, presumably in his thirties, fancies Cressy, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a Quayne couple. Indeed, Cressy is their only daughter, but they do not object when David comes to tell them he wants to marry her. Midge enjoys having their company as she has no other visitors or friends to speak of. The marriage might seem problematic were it not for Midge’s willingness to serve as a friend to her daughter-in-law as well as a doting grandmother when David and Cressy’s son is born. The title of the book is odd, since there is only one wedding in the novel and that takes place “off-stage,” as it were. While the characters are believable, this book gave its author quite a bit of birthing trouble. Perhaps this is, after all, salutary, for the characters—even David’s isolated and absentee father—are plausible for their peculiarities.

By the time Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was published in 1971, it was the result of the author having met and known elderly people, such as her fellow writer Ivy Compton-Burnett, among others.27 The hotel was based on a real London hotel where elderly pensioners lived out their days. Beauman notes cryptically that the book “was the only one of her books to be short-listed for a prize in her lifetime.” Not only that, but the theme, constant with Taylor, was solitude—as Beauman notes: “It is another study in excruciating loneliness.”28 Taylor herself had not experienced solitude for any length of time, but her observational powers were keen. Taylor’s friendship with Ivy Compton-Burnett, as Beauman has it, was one of two inspirations for Mrs Palfrey as well as the profound fact of isolation brought on by time’s rush. The character Ludo is a construct of fiction melding with reality to create a believably grounded character. Mrs Palfrey is not well, has a stroke, and dies in a hospital, but not before Ludo brings her flowers and repays a fifty-pound gift that he refuses to accept as anything other than a loan.

As Beauman intimates, Mrs Palfrey was the only novel of Taylor’s to be short-listed for the esteemed Booker Prize, admittedly in an era when relatively few prizes existed. However, a “lukewarm review” in Times Literary Supplement, as well as carping by Saul Bellow, one of the judges, doomed it to lose to In a Free State, a novel by V. S. Naipaul. (There were four other competitors.) Both comedy and “vicious satire” are evinced in the book, and—as Paul Bailey wrote—Taylor’s talent “is for noticing the casual cruelty that people use to protect themselves from the not always casual malice of others. Her ear for insult is, every so often, on a par with Jane Austen’s.”29 Indeed, Taylor was often compared to Austen, although there are obvious limitations to pairing two English writers who lived a century apart.

The Devastating Boys and Other Stories was brought out in the U. S. by Viking in 1972, comprising some of the most vivid short stories Taylor had ever written. The title piece, reflecting Taylor’s and her husband’s experience hosting two young black boys about six years old from north Kensington was perhaps too factual, one reason that William Maxwell of The New Yorker might have turned it down, as did a number of English editors. Still, the story is vivid, not at all reflecting a negative two weeks as the title might suggest. Another story, “The Fly-Paper,” suggests at its conclusion a kidnapping of an eleven-year-old girl on her way to a music lesson. The motif of the flypaper, close to the story’s end, suggests horror to come but then nothing is overt. Sylvia, the eleven-year-old, is at first impressed by the neat and clean little house to which she has been enticed on her way by a middle-aged woman who had been on the bus. She also notices flypaper on the kitchen window with dying insects struggling to get free. Then a talkative middle-aged man she also saw on the bus suddenly comes in through the back door. There is already a tea setting for three on the kitchen table. The ending is like a punch in the stomach, or as Benjamin Schwarz, the literary editor of The Atlantic, wrote more than three decades later: “This is an almost unbearably terrifying story, especially for parents, in which evil emerges casually from the day-to-day.”30

The collection, like everything else she published, received mixed reviews. Joyce Carol Oates proclaimed a similarity to instances in Taylor’s previous work. However, the themes and underlying motifs in these stories are uncharacteristically venturesome, such as predation upon an unsuspecting child (the aforementioned story), and another about two middle-aged women who had been living together for years (titled “Miss A. and Miss M.”), attesting to the author’s willingness to venture into societal matters not on a grand scale but whittled down to particular individuals and sadnesses that may accrue. When one of the women finally marries, the other kills herself, unable to cope with living alone.

In the fall of 1973, Taylor began writing what she knew would be her final novel, Blaming. We blame each other, the book seems to be saying, and certainly another person provides a convenient target for grief, outrage, small annoyances—a sundry list of perceived human foibles. But the characters are hardly outrageous enough for too much blame. In some ways, Amy—suddenly widowed as she and her husband Nick are about to return to England from a holiday in Greece—represents the author herself, except that Taylor was never a widow. Indeed, she knew she had cancer when she wrote this book over a year and a half, completing it (a second draft, according to Beauman) in May 1975. Liddell observes that the book lacked more than a first draft, but he was not close to the situation, although he kept in steady epistolary contact with Taylor until shortly before she could no longer hold a pen to write. As noted above, Maud Eaton, the New Zealand friend of an earlier time, is portrayed in the novel as Martha Larkin, a younger American, who befriends Amy and helps her through the immediacy of Nick’s sudden death (he had been quite ill, although we do not know his precise misfortune).

The myriad characters and ambitions, such as they are, that abound in Taylor’s stories and novels are very English depictions, although comparisons with other writers—in Canada, Alice Munro, and originally from Colorado, Jean Stafford—may engage the reader by human predicaments in their own lifetimes and spheres. While Munro’s writing extended through the first decade of the twenty-first century, she wrote of life as she encountered it and spun her stories through the travails and odd joys of living. Stafford won the Pulitzer Prize in 1970 in large part because her characters were universal in their woes and small triumphs, not isolated as eccentrics. Elizabeth Taylor was concerned with twentieth-century British life as she knew it. This is her great accomplishment: the description of a troubled century as she saw her fellow mortals behold both joy and grief. She would have wanted no less than that as a writer.

1 Until the post World War II years, many British women who aspired to write fiction or poetry were actively discouraged from attempting higher education, some–such as Virginia Woolf–eschewed it altogether in favor of what we recognize now as autodidactism. Indeed, self-education or private tutoring in the case of Woolf did not hamper her later. She married well, too, and with her husband Leonard founded the Hogarth Press, through which her own books as well as those of others were published.

2 Their correspondence, kept on his side by Russell, proved quite helpful to Taylor’s biographer, Nicola Beauman, who enticed him to let her use the letters in part for her book, The Other Elizabeth Taylor (Persephone Books, 2009). Russell finally was married in his late thirties to a woman thirteen years younger named Eunice. They had a son in 1960—Colin—and appear to have had a contented life, although he never got over Elizabeth completely, according to Beauman.

3 It is worth noting that after the Greek junta deposed the monarchy in 1967, Taylor never visited the country again, despising right-wing dictatorships, although Liddell, who by then had settled in Athens permanently, observed later that the Greek economy was not affected by the change in government, or for that matter the atmosphere in the country itself. Nonetheless, Taylor’s boycotting of her favorite foreign country in the last years of her life is significant as a statement of principle.

4 Robert Liddell, Elizabeth and Ivy, (Peter Owen, 1986), 15.

5 Elizabeth Taylor, At Mrs. Lippincote’s (Knopf, New York, 1945), 149-150.

6 Ibid., 185-186.

7 Elizabeth Taylor, Palladian (Knopf, 1947), 127-128.

v8 Robert Liddell, “Afterward” to A View of the Harbour, Knopf (1947, 1987), 301-309. Liddell wrote this essay in Greece in 1986, more than a decade after Taylor’s death.

9 Elizabeth Taylor, A Game of Hide and Seek (New York Review Books reprint, 1951, 2010), 104.

10 Taylor uses this nickname for Vincent also in A Game of Hide and Seek.

11 Elizabeth Taylor, The Sleeping Beauty (The Dial Press, New York, 1953), 136.

12 Robert Liddell, Elizabeth and Ivy, (Peter Owen, London, UK, 1986), 45.

13 Elizabeth Taylor, Hester Lilly and 12 Short Stories, (Viking, 1954), 43.

14 Taylor, op. cit., 188.

15 Ibid., 191.

16 Beauman, op. cit., 285.

7 Ibid., 285-286.

18 “The Blush” in Elizabeth Taylor, The Blush and Other Stories (The Viking Press, New York, 1959), 35.

19 Beauman, op. cit., 304-305.

20 Taylor, op. cit., 40-41.

21 Susannah Clapp, “Introduction” –forward to In a Summer Season, by Elizabeth Taylor (The Dial Press, New York, 1961, 1982), 5.

22 Liddell, op. cit., 102.

23 Still, the characters are vividly depicted. Flora, in another setting and another time, might seem like a figure in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, but it is England in the early 1960s before social media, cell phones, and the Internet. Indeed, this is the case with all of Taylor’s fiction – these electronic enhancements did not emerge until a generation after Taylor’s death.

24 Elizabeth Taylor, The Soul of Kindness, (Virago, New York, 1964, 2010), 180-181.

25 Elizabeth Taylor, A Dedicated Man and Other Stories (Viking, New York, 1965), 132.

26 Elizabeth Taylor, Mossy Trotter. (Illustrations by Laszo Acs. Harcout, Brace & World, New York, 1967), 97.

27 The honorific normally spelled “Mrs.”–with a period–is spelled without it all through this novel; hence, my reference is “Mrs” as well.

28 Beauman, op. cit., 363.

29 Quoted in Beauman, Ibid., 364-365.

30 “The Other Elizabeth Taylor,” Benjamin Schwarz, The Atlantic, September 2007.

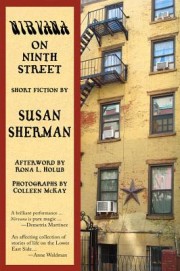

Click here to purchase At Mrs. Lippincote's at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase You'll Enjoy It When You Get There: The Stories of Elizabeth Taylor at your local independent bookstore

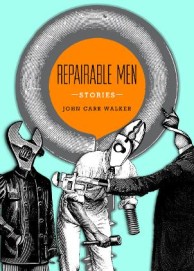

Click here to purchase A View of the Harbour at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase A Game of Hide and Seek at your local independent bookstore

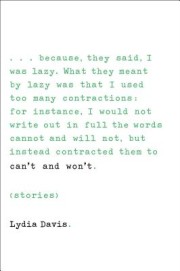

Click here to purchase Angel at your local independent bookstore

Dorothea Lasky

Dorothea Lasky

Soumitra Chatterjee

Soumitra Chatterjee