by Abel Debritto

Editor’s Note: This year is the thirtieth anniversary of Charles Bukowski’s death, and today, August 16th, is the author’s birthday. To commemorate, Abel Debritto, author of Charles Bukowski, King of the Underground (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) and A Catalog of Ordinary Madness (Chatwin Books, 2024), and editor of six Bukowski collections for Ecco/HarperCollins, offers an overview of all of Bukowski’s major books to date.

Fifty-seven major books in fifty-seven years. Charles Bukowski’s gargantuan literary output is staggering by most accounts: over 5,500 poems, almost 1,000 prose pieces, and six novels over a span of fifty years. Add to that some 500 poems lost in the mail in the 1960s—those alone are equivalent to some authors’ Complete Works. For a thought-provoking, controversial writer who always seemed to be on a binge, Bukowski was prolific beyond words. Writing was both his disease and his crutch. Some of it was obviously dross, an exercise to get the good stuff going, but at his very best, Bukowski had a unique knack for squeezing magic out of the ordinary with unsurpassed simplicity. Legions of aspiring writers have tried unsuccessfully to emulate his artfully artless style.

For better or worse, Bukowski had little time for arcane metaphors, synecdoches, and iambic pentameters. He was so busy writing “the next line” that he didn’t edit any of the fifty-seven books listed below. His longtime publisher John Martin was entirely responsible for selecting, arranging, and editing the work that appeared under his Black Sparrow Press imprint; Bukowski read the proofs and green-lighted all projects, and Martin put them out. Overall, Bukowski didn’t complain about Martin’s editorial decisions, save in the case of Women: As he said in a letter, “My writing is jagged and harsh, I want it to remain that way, I don’t want it smoothed out.” A second printing was immediately issued, restoring Bukowski’s unadulterated writing.

A case could be made for the aggressive editing that plagued (and marred) several posthumous publications—not a minor matter since twenty-nine of the fifty-seven books discussed below have been released after Bukowski’s death, and rivers of virtual ink have been spilled to pinpoint the culprit of those countless substandard edits. Although the jury is still out, the consensus seems to be that Bukowski didn’t make the bulk of those changes.

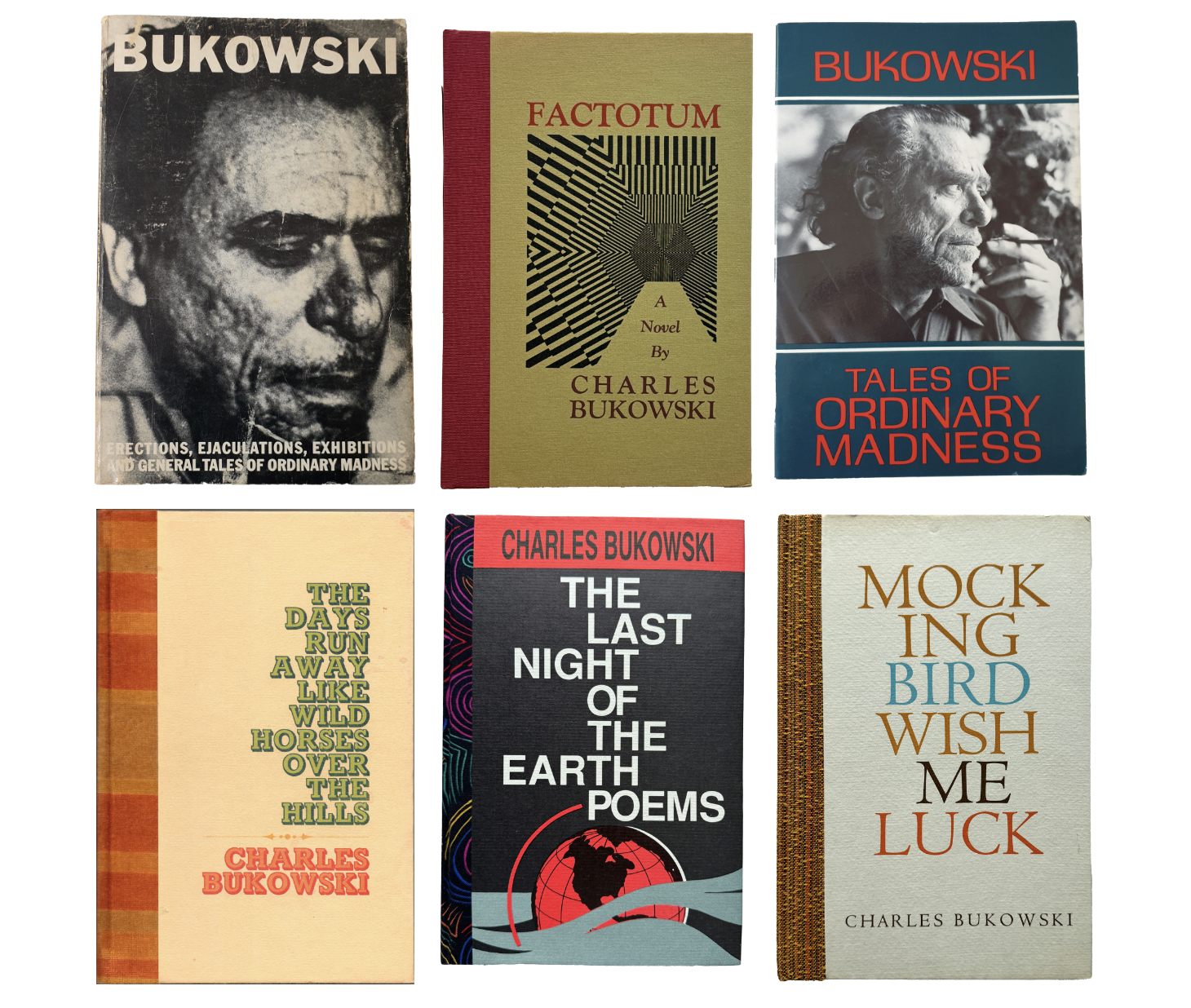

Egregious editing is not the only issue when it comes to Bukowski. There are quite a few myths about him and his work, some of them fueled by the man himself, who got a kick out of deliberately blurring reality and fiction. He was accused of being a male-chauvinist pig long before cancel culture became prevalent, but that misconception largely stemmed from short excerpts from Women and Love Is a Dog from Hell, a lilliputian portion of Bukowski’s actual output. Similar candid, blunt accusations—that he was a drunk lecher, a ludicrous dilettante, a vicious typist, America’s sewer Shakespeare, the bukkake of bad poetry—were but parts of a very distorted picture. To understand Bukowski fully, a quick look at a few excerpts is simply not enough. Tackling all fifty-seven books below might be a bit of a challenge, but ideal contenders to provide a better grasp of Bukowski’s range include: The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills; Mockingbird Wish Me Luck; Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness; Factotum; Ham on Rye; and The Last Night of the Earth Poems.

Misconceptions aside, thirty years after Bukowski’s passing, his spirit still looms large, much to the chagrin of his loudly sensationalist detractors. Translated into over twenty languages and with millions of copies of his books sold worldwide, Bukowski is a reliable steady seller: Some 10,000 copies of Essential Bukowski: Poetry are regularly sold per year in the U.S. alone—a remarkable achievement for a poetry collection in this age. His critical reception is no small feat, either: over a thousand print books and articles are devoted to his work, not to mention hundreds of online reviews and almost 200 anthology appearances, including some highbrow publications. Not bad for the soi-disant drunken bard of the underdog.

It’s hard to establish Bukowski’s popularity in a time when most new releases are forgotten as quickly as they hit the shelves, but younger generations are still clearly thrilled by the work of such an outrageous hell-raiser. One of his best-known quotations, printed in Life Magazine in 1988 when Bukowski was almost seventy, perhaps explains his appeal to the ever-rebellious nature of the youth:

We are here to unlearn the teachings of the church, state, and our educational system. We are here to drink beer. We are here to kill war. We are here to laugh at the odds and live our lives so well that Death will tremble to take us.

No wonder, then, that Bukowski’s books are among the most frequently stolen in bookstores. And if that seems like a dubious indicator of the undying, undisputed demand for his literary output for those who have outgrown or simply dislike it, here’s a stunning fact: all of the work published in these fifty-seven books remains in print.

Three decades after his death, there’s no stopping America’s Dirty Old Man.

.

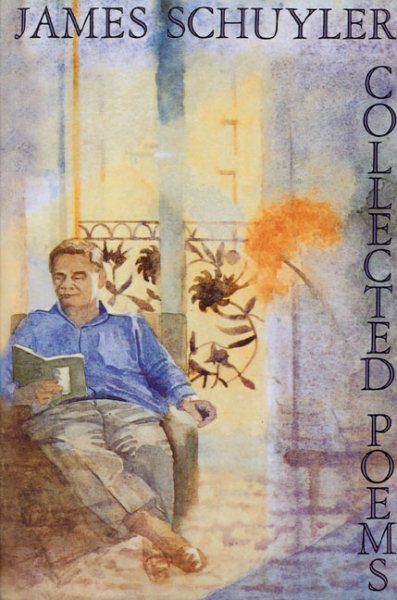

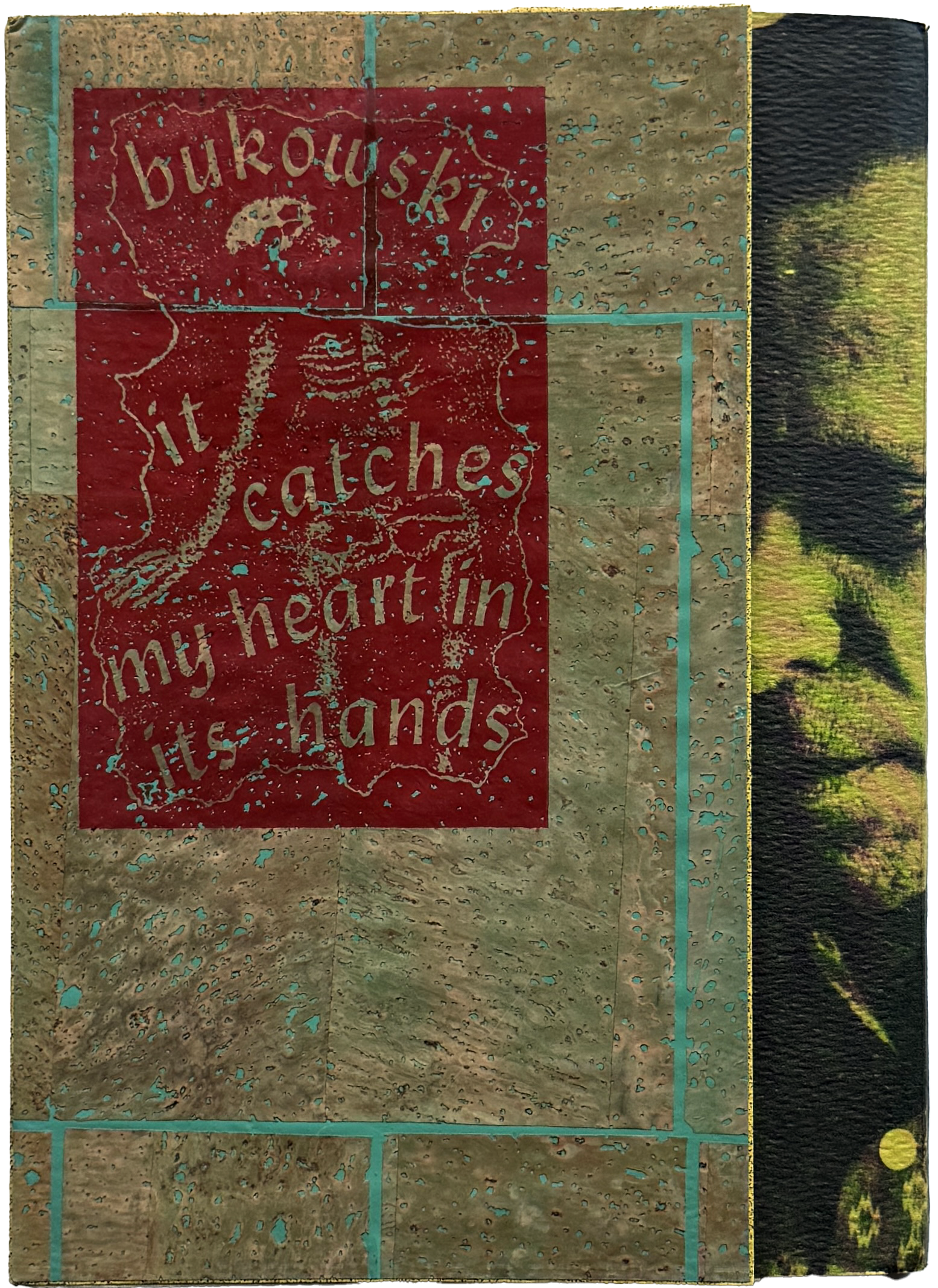

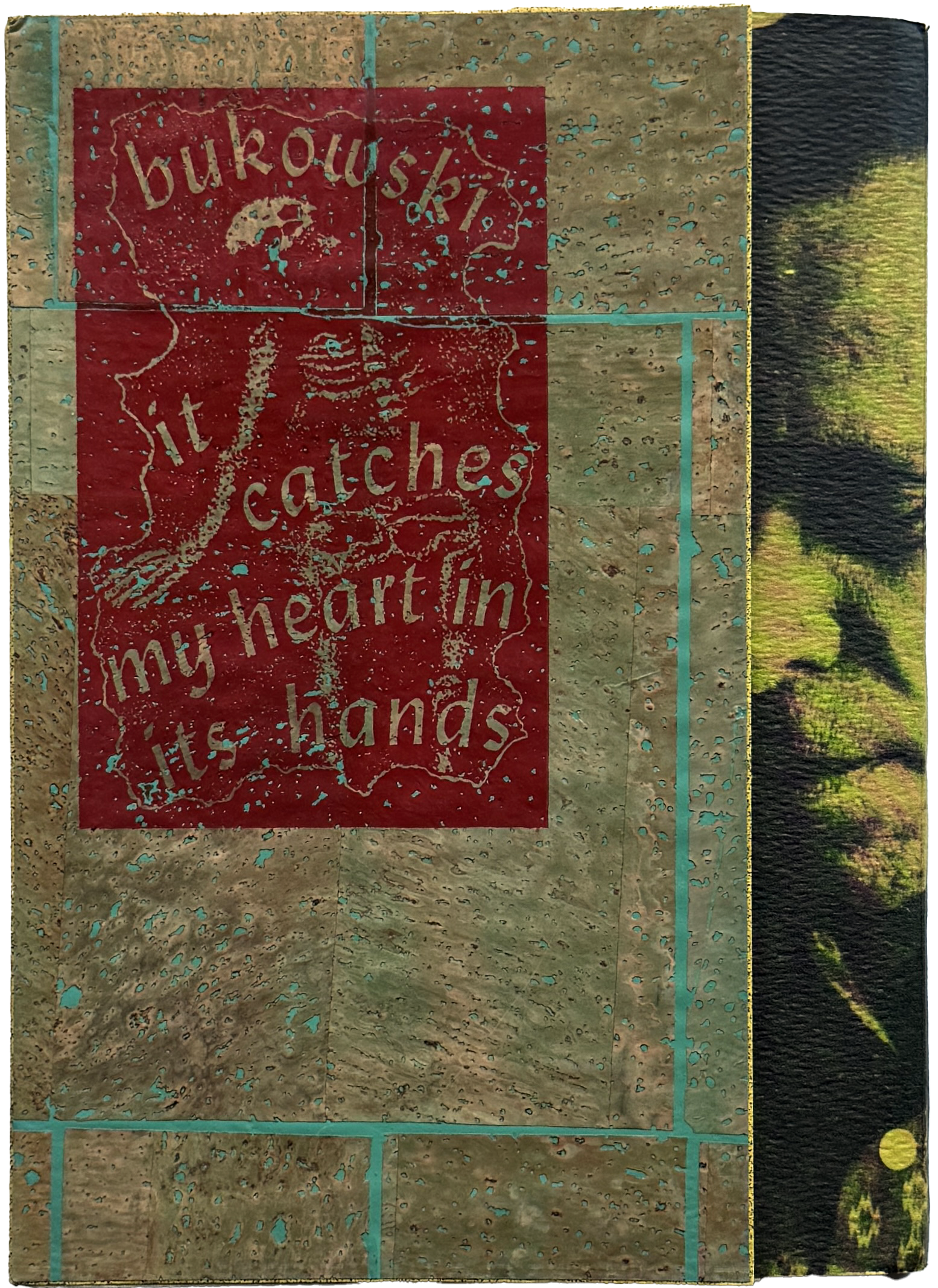

1. It Catches My Heart in Its Hands, Loujon Press, 1963

1. It Catches My Heart in Its Hands, Loujon Press, 1963

The book that began it all—most publishers and editors discovered Bukowski here. Edited by Jon and Louise Webb, it was a laborious letterpress project limited to 777 copies, with Jon Webb’s discerning eye picking the best poems written between 1955-1963. An early milestone by all accounts, full of lyrical imagery, so scant in later years. Raw and poetic, even surreal at times, it was praised to the skies by Henry Miller and other writers. Critic William Corrington claimed the poems were “the spoken word nailed to paper.” Bukowski was compared to Baudelaire, Rimbaud, W. C. Williams, Celine, and Artaud. The underground legend was born here. Essential: “The Tragedy of the Leaves,” “Old Man, Dead in a Room,” “The Twins.”

.

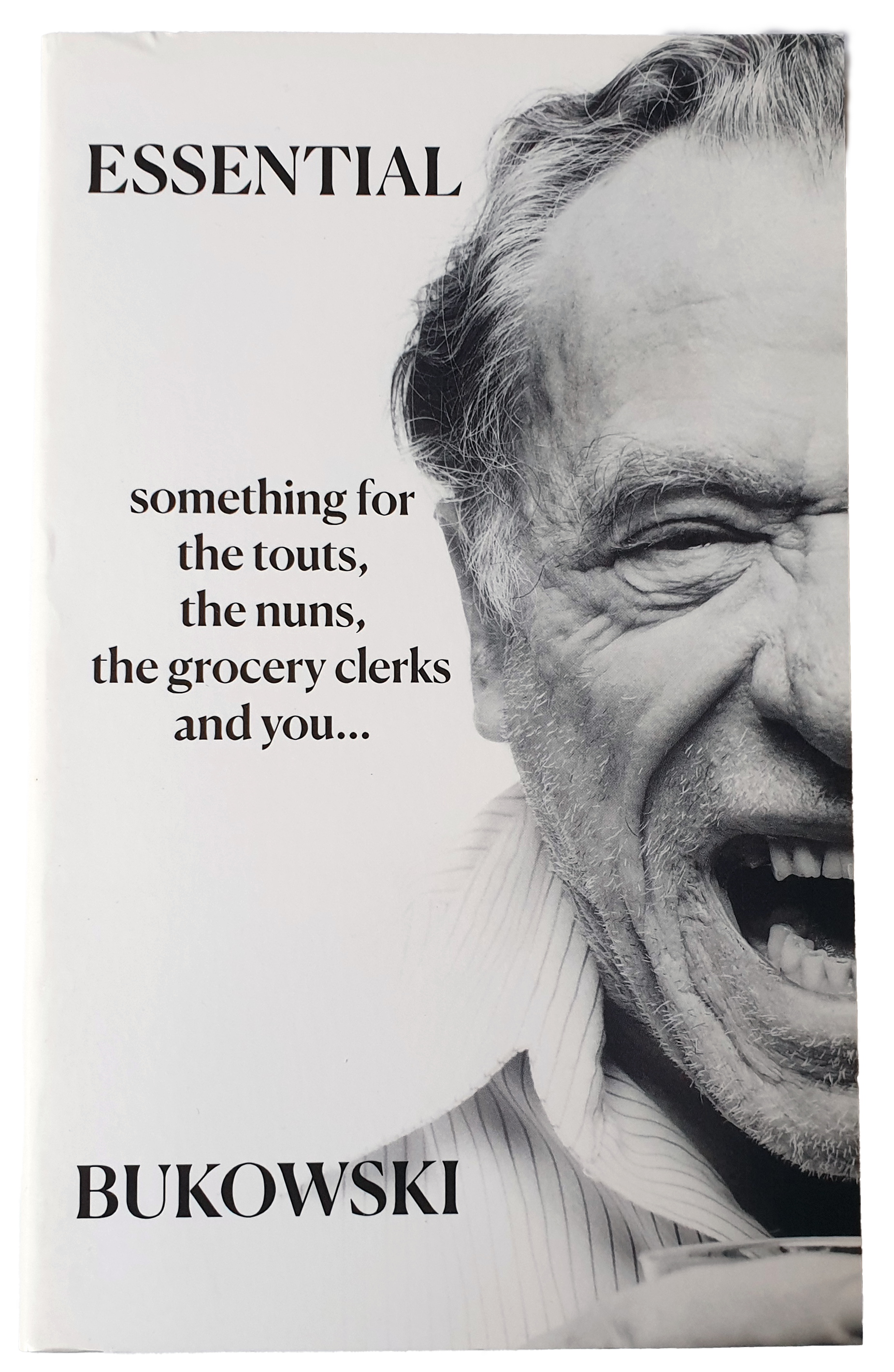

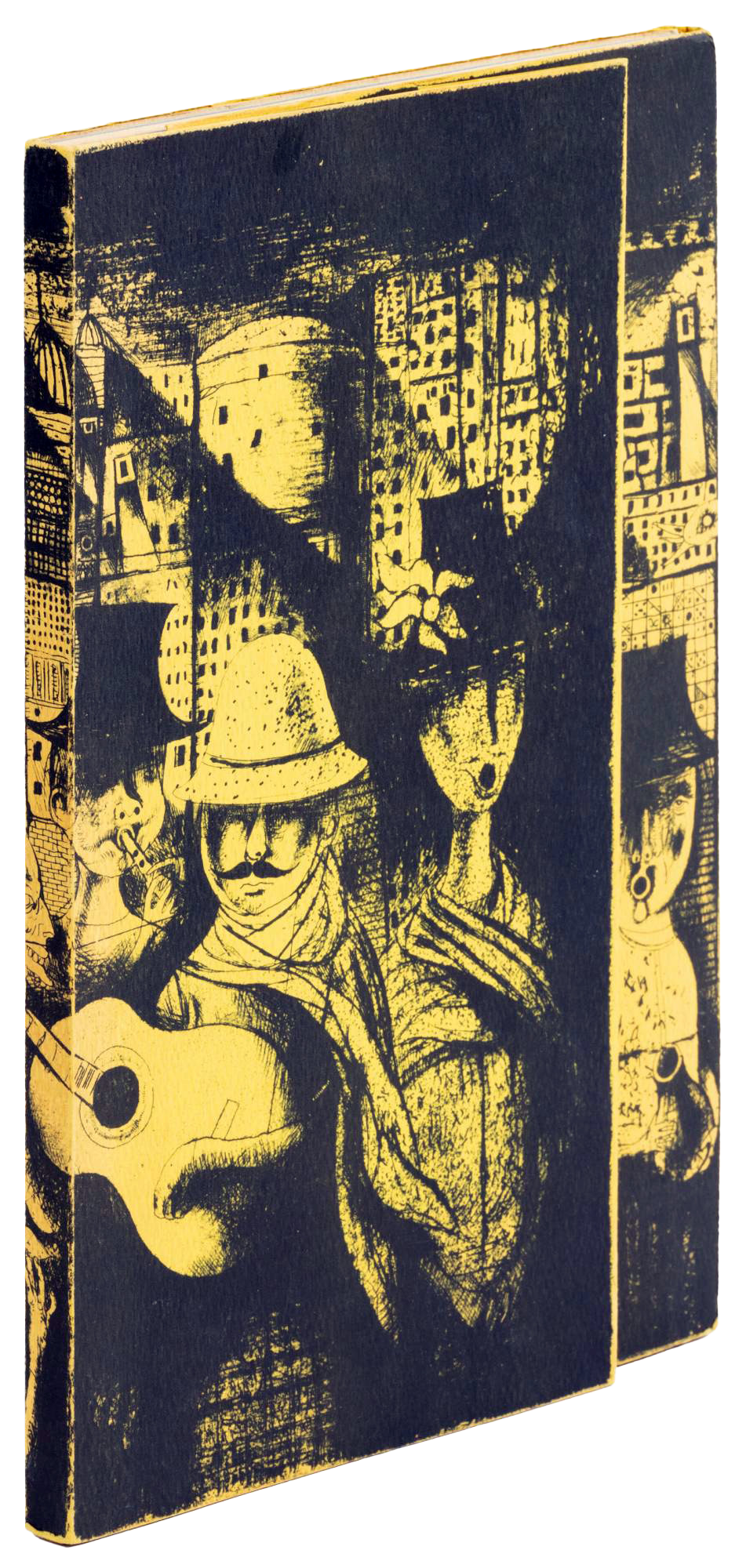

2. Crucifix in a Deathhand, Loujon Press, 1965

2. Crucifix in a Deathhand, Loujon Press, 1965

Another lavishly produced book by the Webbs. Unlike It Catches, all poems were new; Bukowski wrote the bulk of them during a very hot month in New Orleans. Years later, Bukowski said it didn’t represent his best work. Still, Miller maintained that Bukowski was “one of the few poets of today I like, the poet satyr of today’s underground.” A genuine labor of love that helped Bukowski become popular in the alternative literary scene. Essential: “Something for the Touts, the Nuns, the Grocery Clerks and You,” “No. 6,” “They, All of Them, Know,” and the title poem.

.

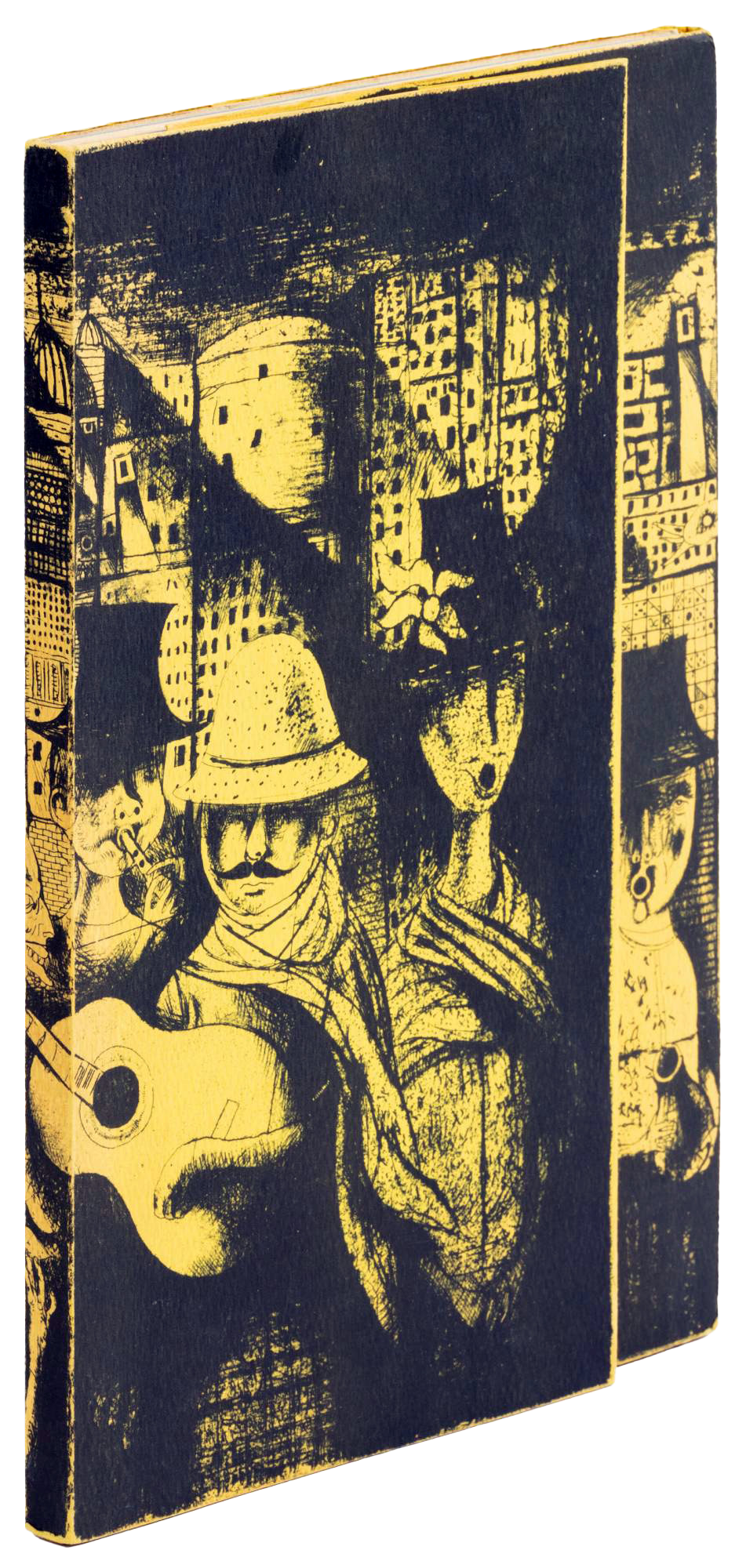

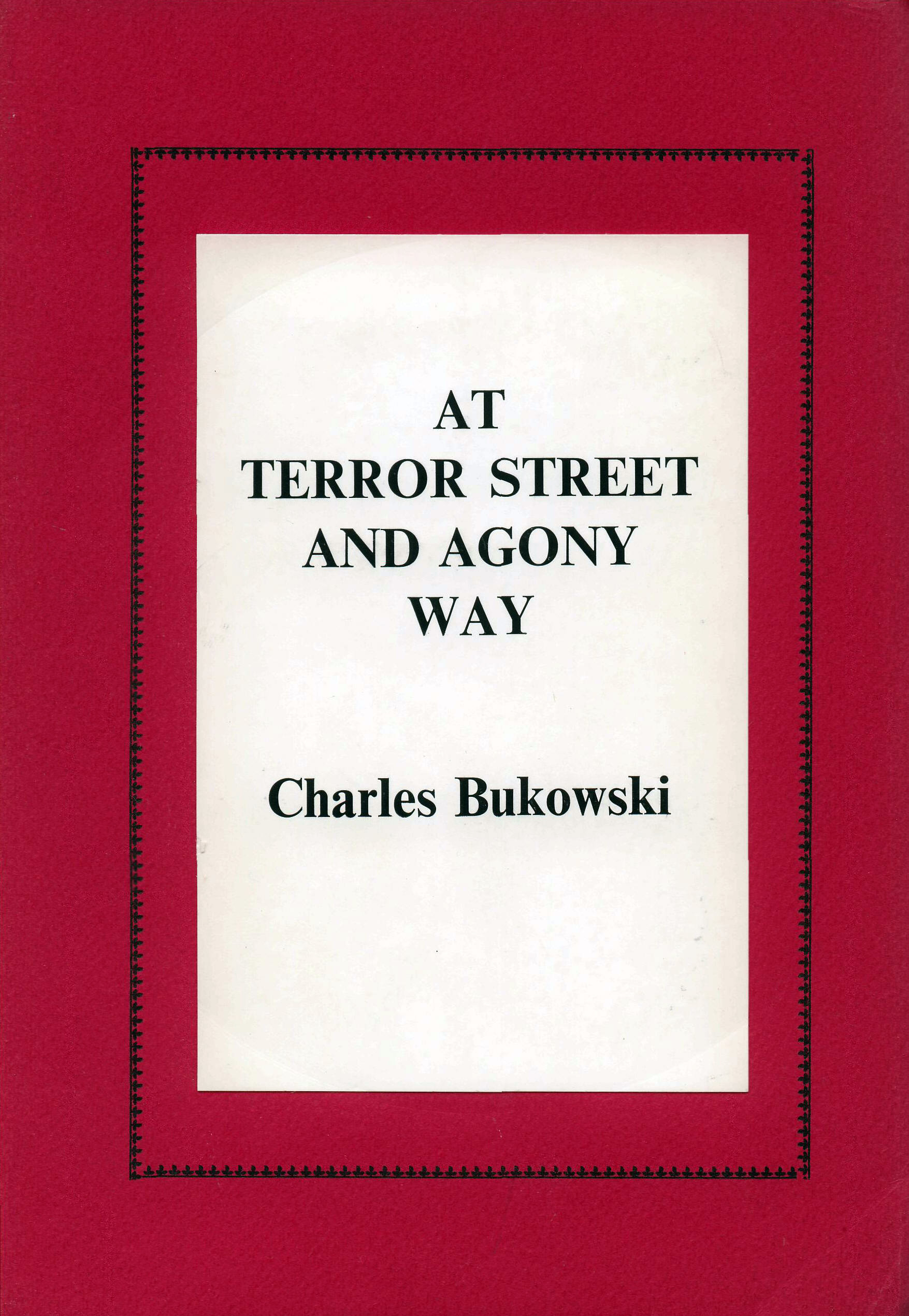

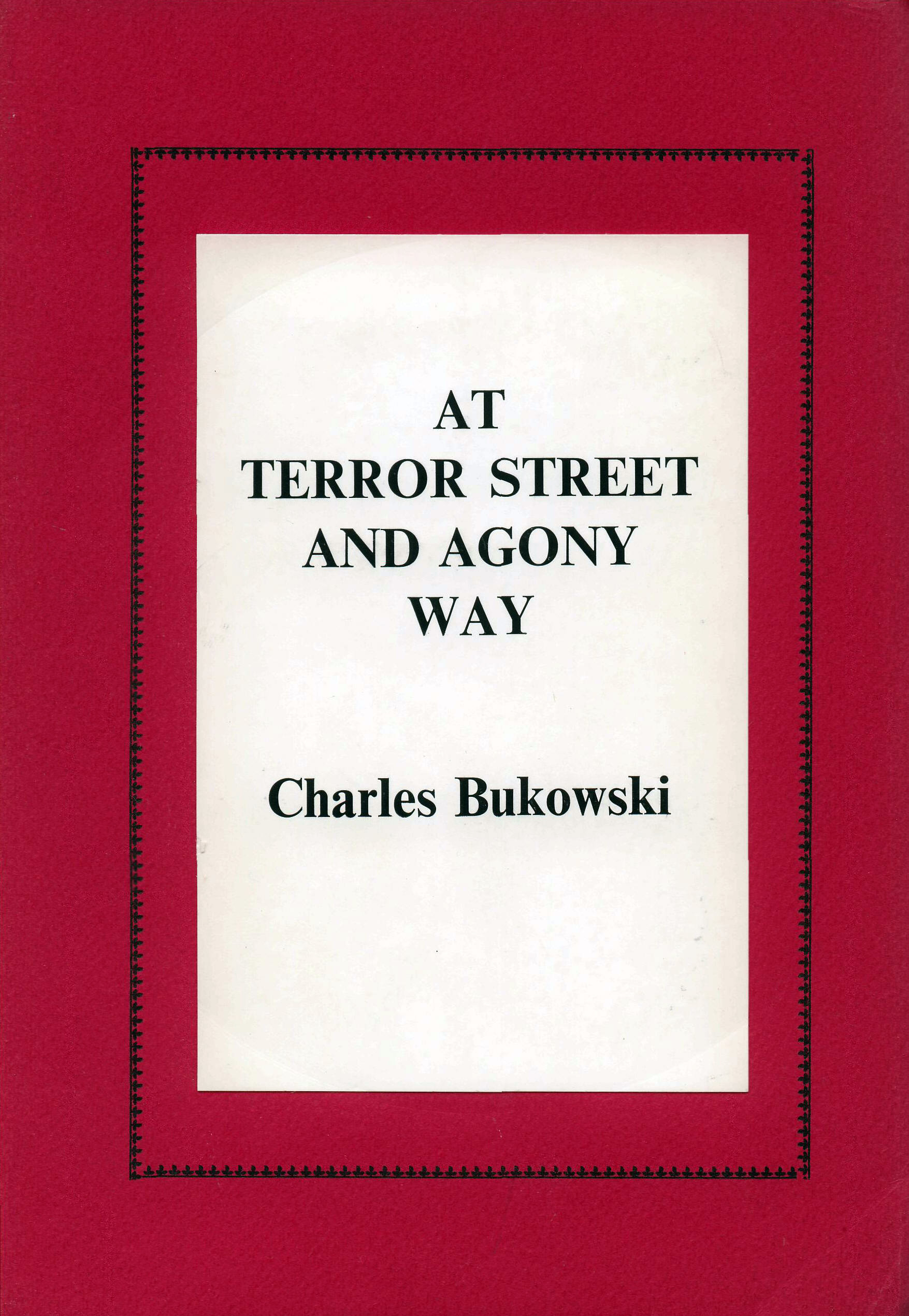

3. At Terror Street and Agony Way, Black Sparrow Press (BSP), 1968

3. At Terror Street and Agony Way, Black Sparrow Press (BSP), 1968

According to legend, John Martin founded the now-mythical Black Sparrow Press to publish Bukowski. After a few initial broadsides, At Terror Street was the first full-length book printed by BSP. The “unholy alliance,” as Bukowski called it, was sealed now and then. Most poems had been previously rejected by little magazine editors and were rescued by poet John Thomas, who had recorded them on tape. An early, unsatisfactory attempt at showcasing Bukowski’s unique voice. Essential: “True Story,” “I Met a Genius,” “John Dillinger and Le Chasseur Maudit.”

.

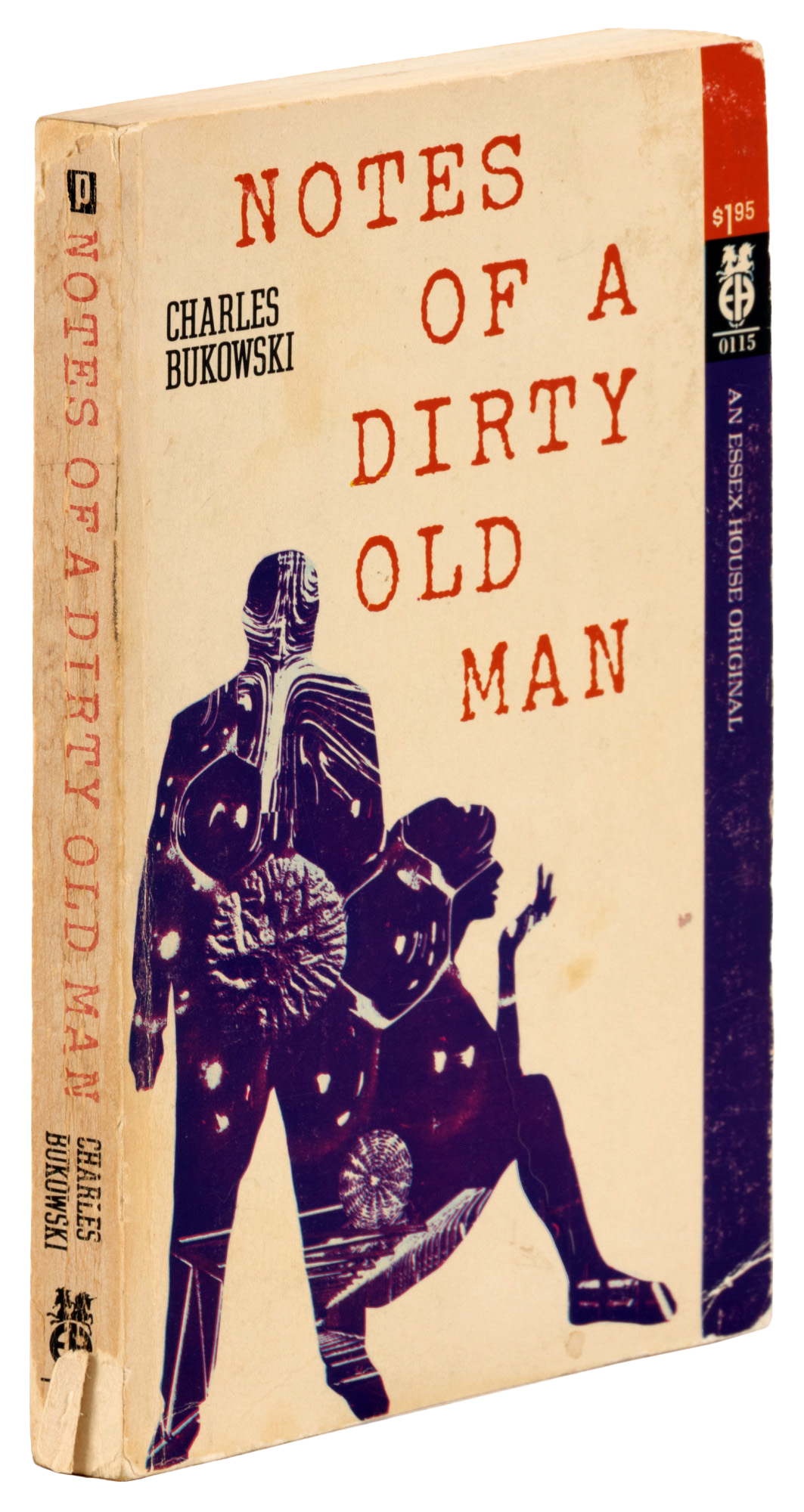

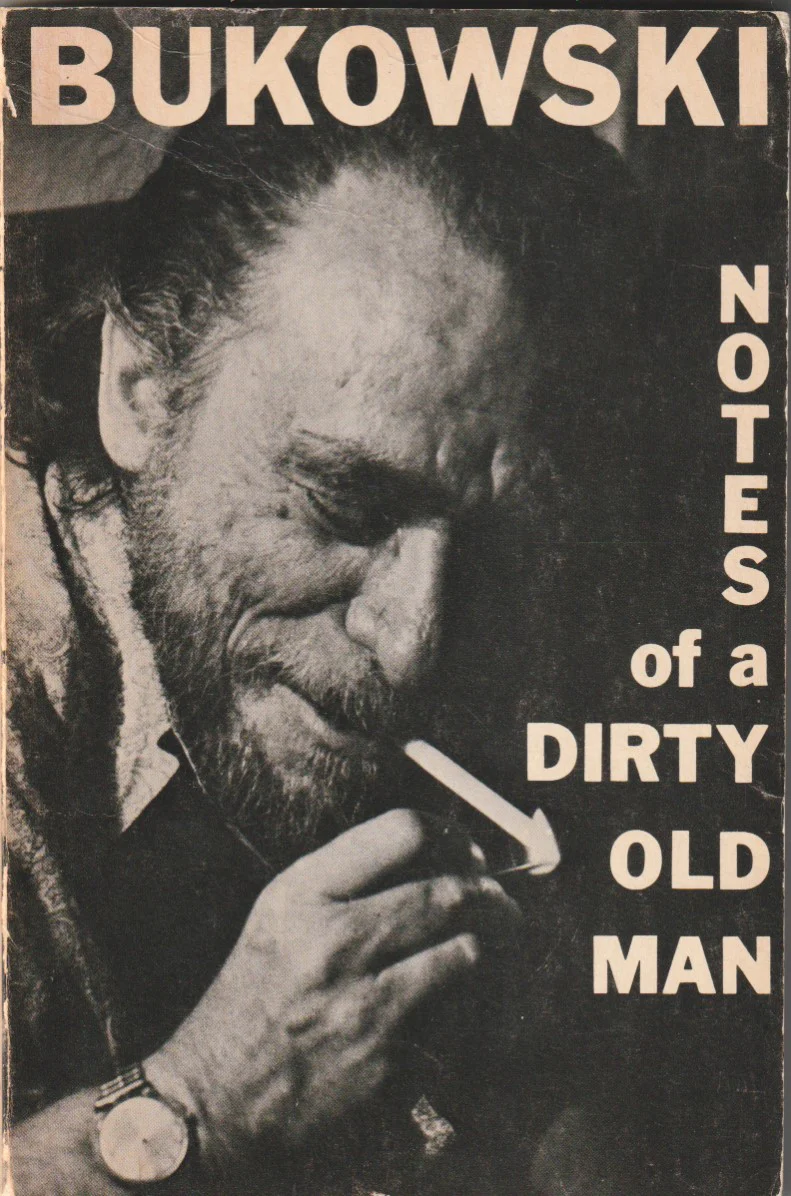

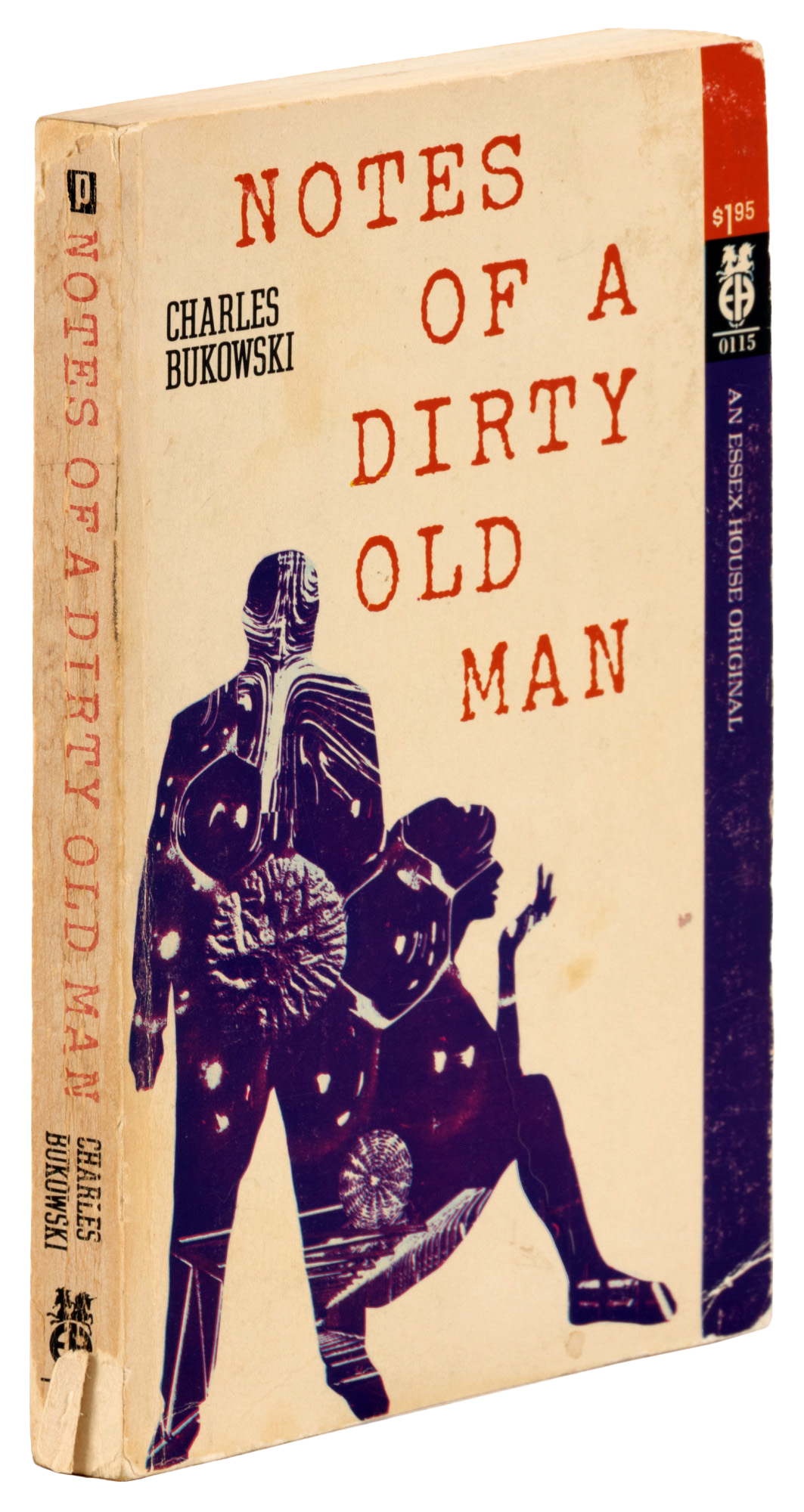

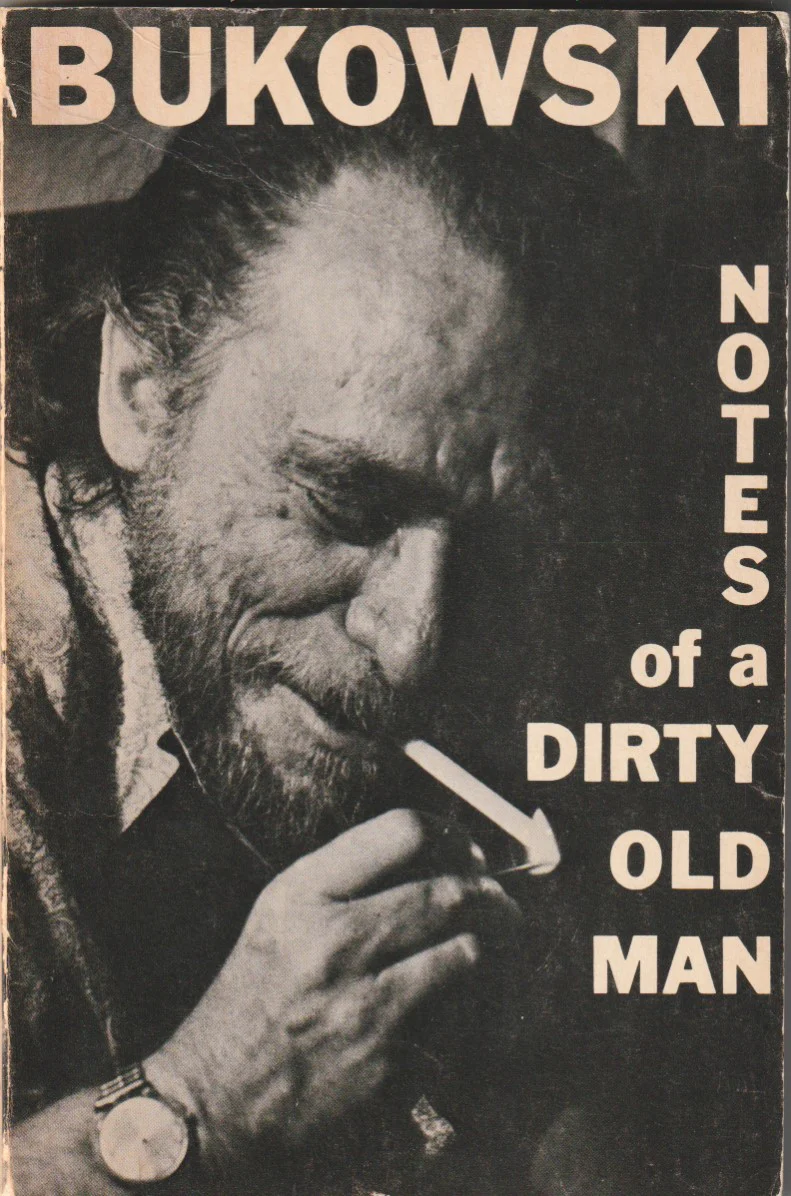

4. Notes of a Dirty Old Man, Essex House, January 1969

This and the next book propelled Bukowski into small press stardom, becoming the indisputable King of the Underground—as an unwanted side effect, the FBI began to monitor his activities and publications. Martin at BSP and Donald Allen at Grove Press tried to get the rights, but Essex House offered more money to Bukowski. Tagged “endlessly offensive” by critics, these forty-two “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” columns, with hilarious sex-as-tragicomedy undertones, gained Bukowski thousands of readers. The 28,000 copies of the first printing were sold out in months. It was translated into German the next year, getting favorable reviews in major newspapers. Reissued by City Lights in 1973. Essential: the “Frozen Man Stance” section, and the Baldy story.

offensive” by critics, these forty-two “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” columns, with hilarious sex-as-tragicomedy undertones, gained Bukowski thousands of readers. The 28,000 copies of the first printing were sold out in months. It was translated into German the next year, getting favorable reviews in major newspapers. Reissued by City Lights in 1973. Essential: the “Frozen Man Stance” section, and the Baldy story.

.

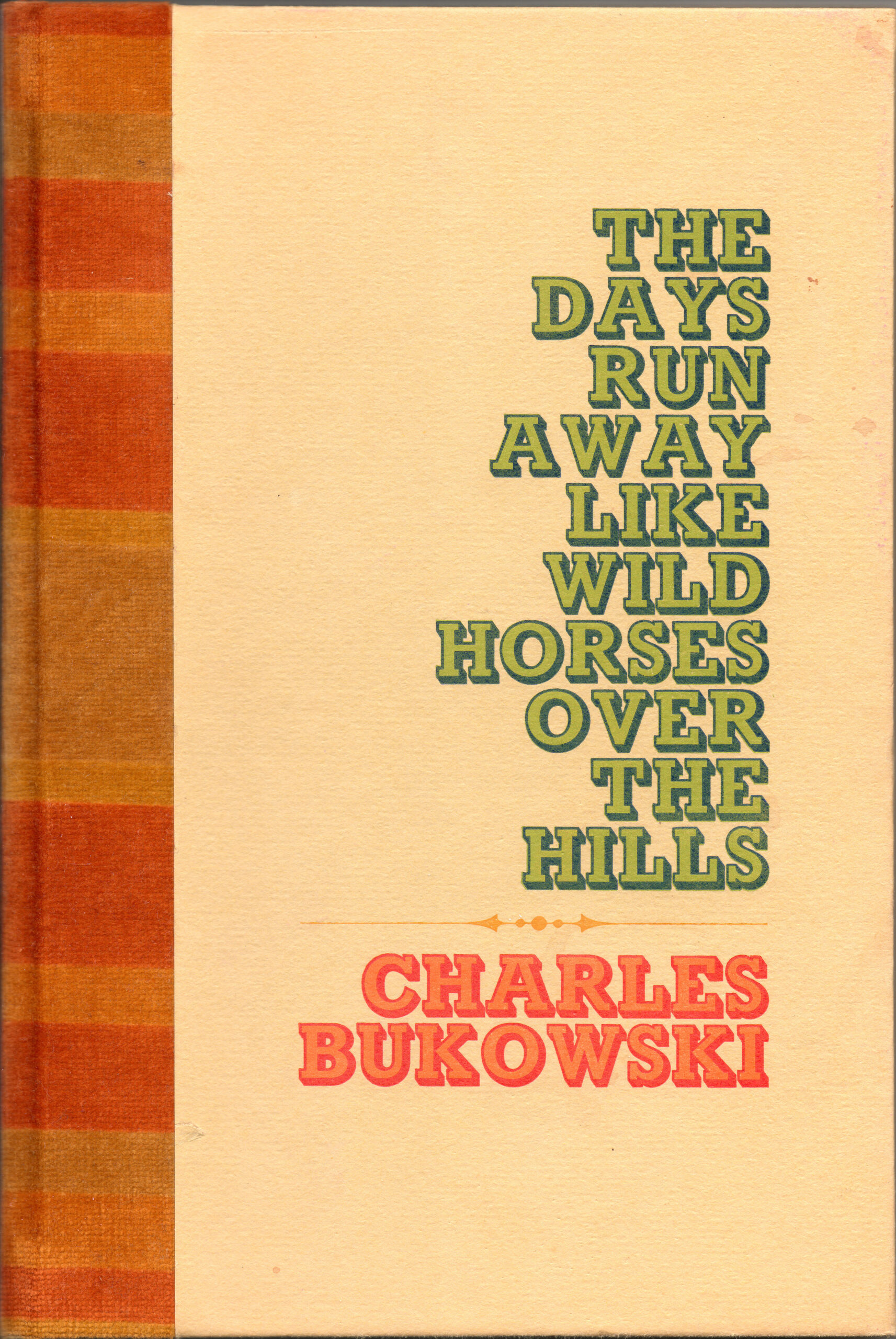

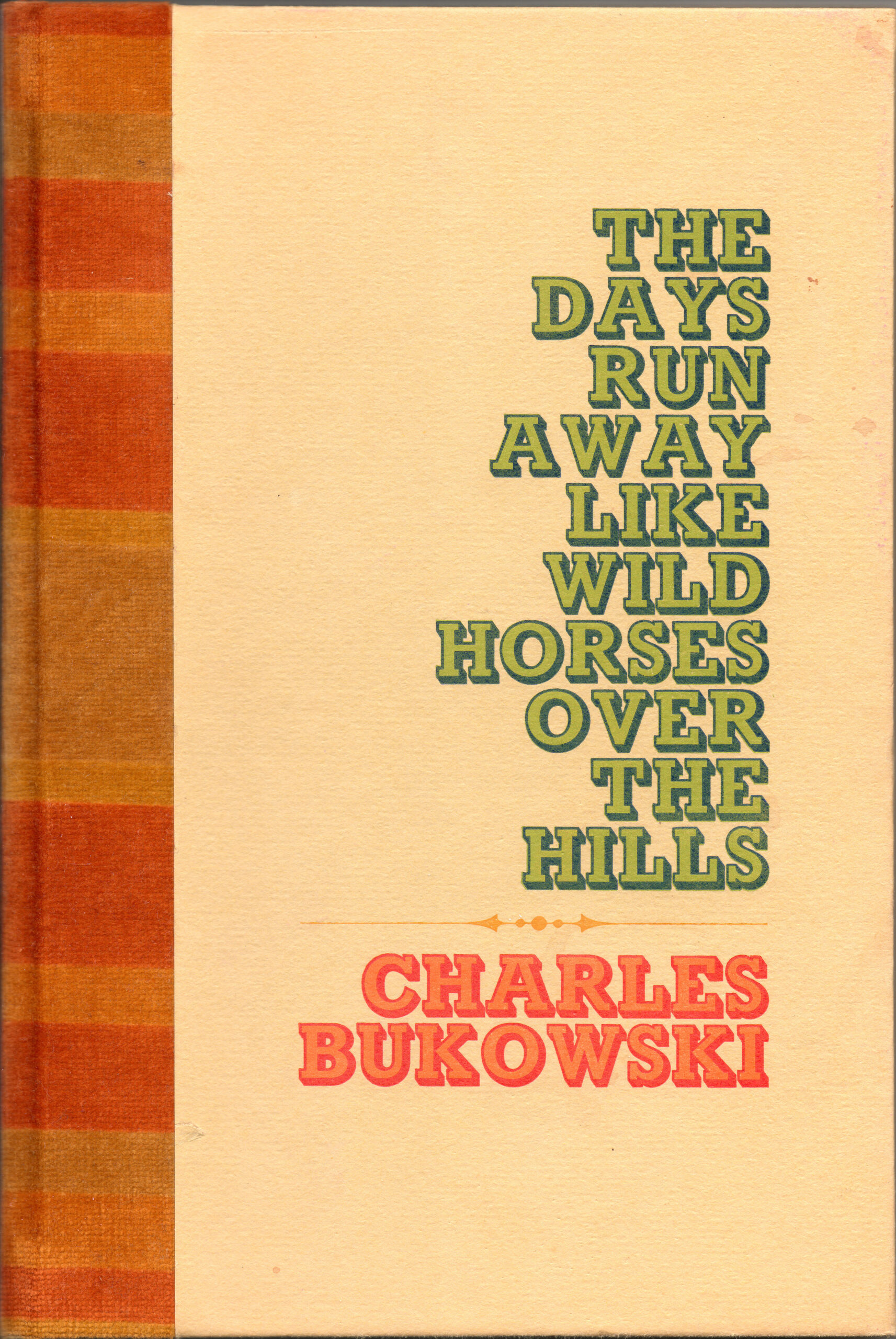

5. The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills, BSP, December 1969

5. The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills, BSP, December 1969

To many, Bukowski’s best poetry book. Presented by bibliographer Sanford Dorbin and Martin as a retrospective exhibit of the strongest poems published in the little magazines. Sensitive, lyrical, with some tough-guy imagery thrown in, making it accessible to the layman. A blast of life-affirming energy that made Martin call Bukowski “a contemporary Whitman who took risks with long, extravagant lines.” Featuring Barbara Martin’s iconic cover, biographer Howard Sounes considered it a “milestone book.” Barely a month after publication, Bukowski was called an “American legend” by reviewers, and Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean Genet were quoted—apocryphally so—as saying that he was “the best poet in America” in the Los Angeles Times. Essential: “As the Sparrow,” “These Things,” “For Jane: With All the Love I Had, Which Was Not Enough,” “A Poem Is a City,” “Spring Swan,” “Finish.”

.

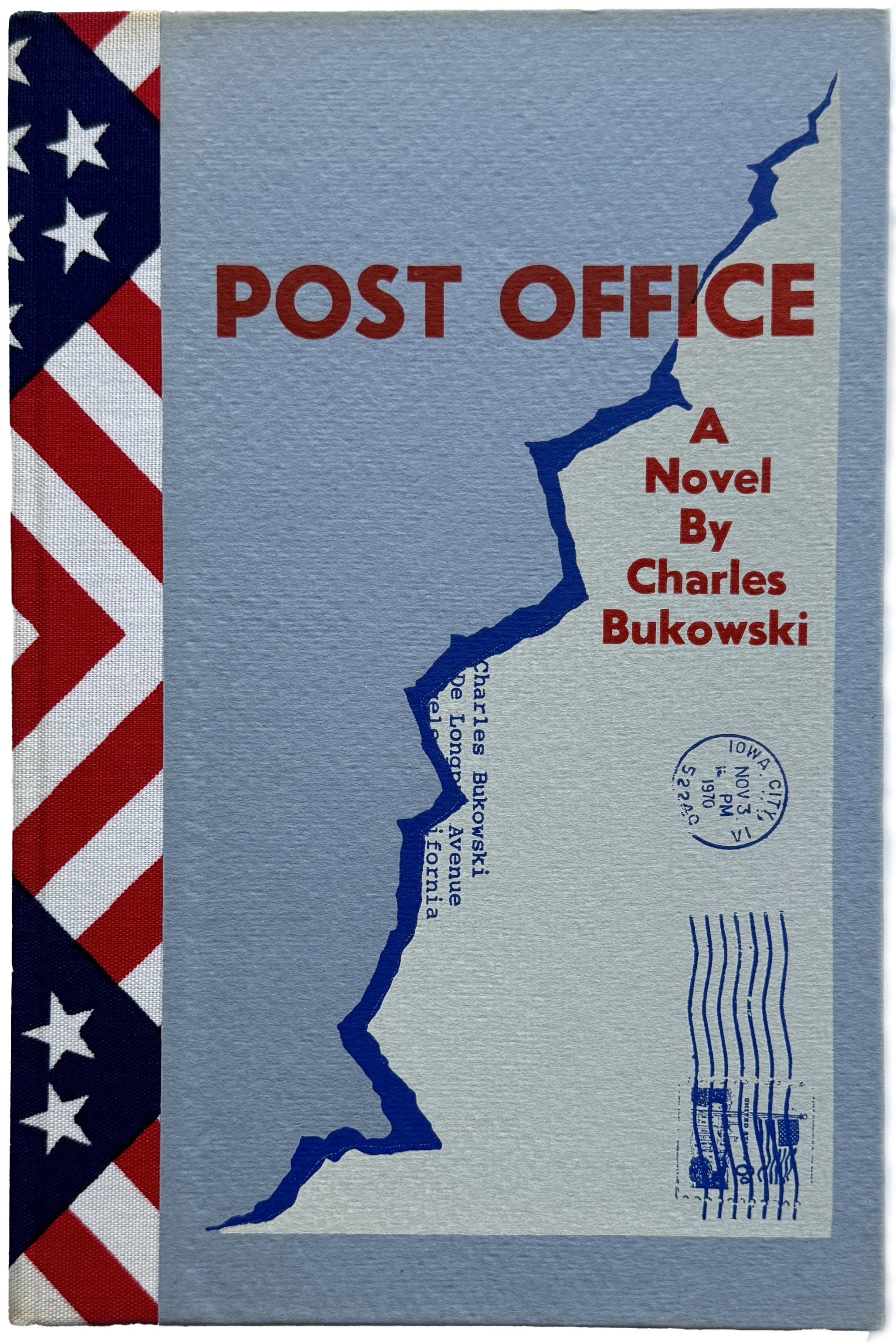

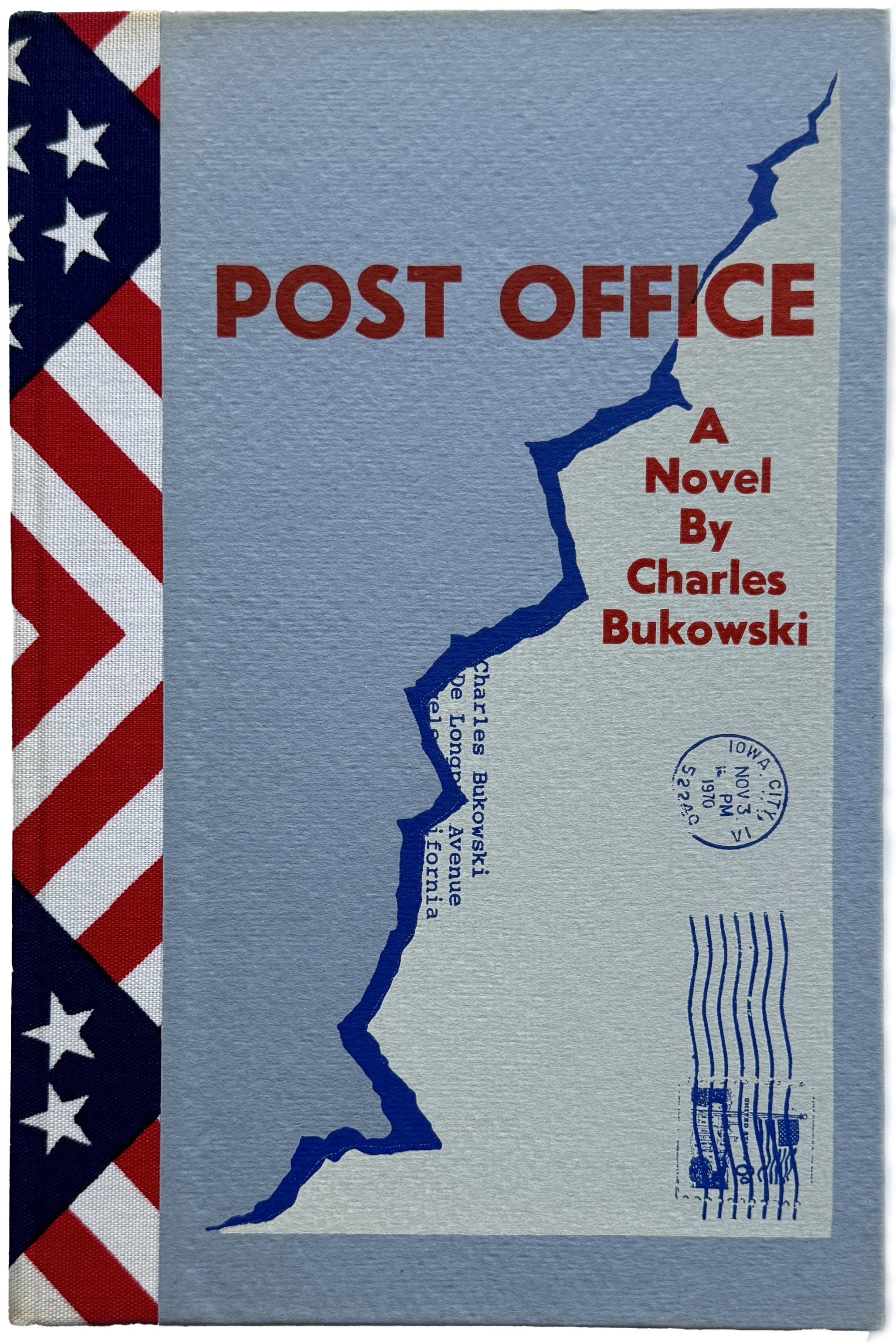

6. Post Office, BSP, 1971

6. Post Office, BSP, 1971

After a couple of failed attempts—A Place to Sleep the Night (1956) and The Way the Dead Love (1966)—Martin prodded Bukowski into writing his first novel on the hunch that his fiction would sell even better than his poetry. Shortly before, Martin had helped Bukowski quit his job at the post office to become a full-time writer by promising him a monthly $100 check for life, whether he wrote or not. Fearful of going bankrupt, Bukowski finished Post Office in record time: “I wrote this novel in 20 nights on a pint of whiskey a night, some cigars plus symphony music on the radio. It was easy.” This hilarious, spirited account of the misadventures of his alter ego Henry Chinaski as a postal clerk, written in short chapters with a brisk pace reminiscent of Dos Passos and his beloved John Fante, became a cult hit upon release. A script was completed by writer Don Carpenter in 1977, but the movie was never made. Essential: the scenes with Joyce.

.

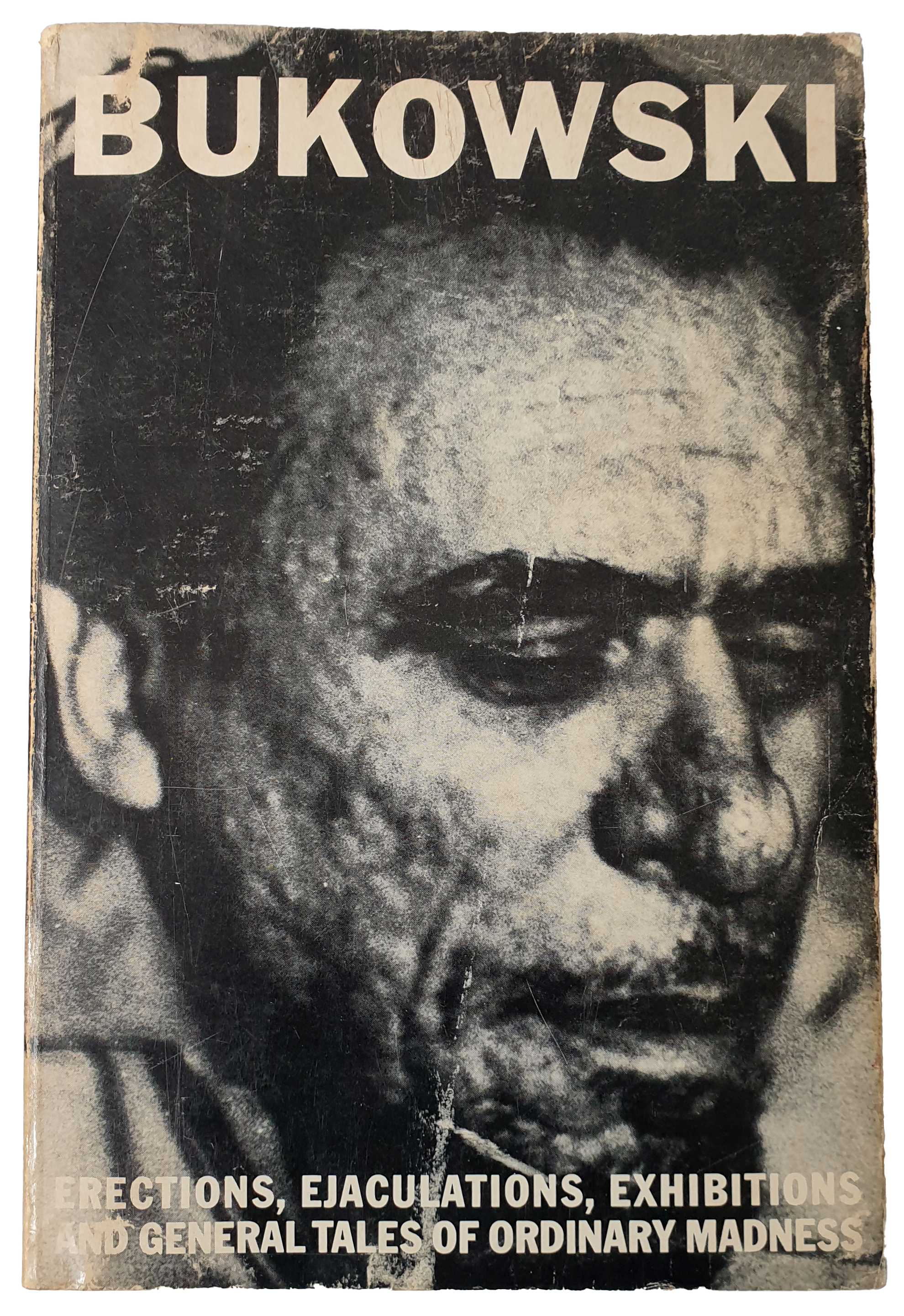

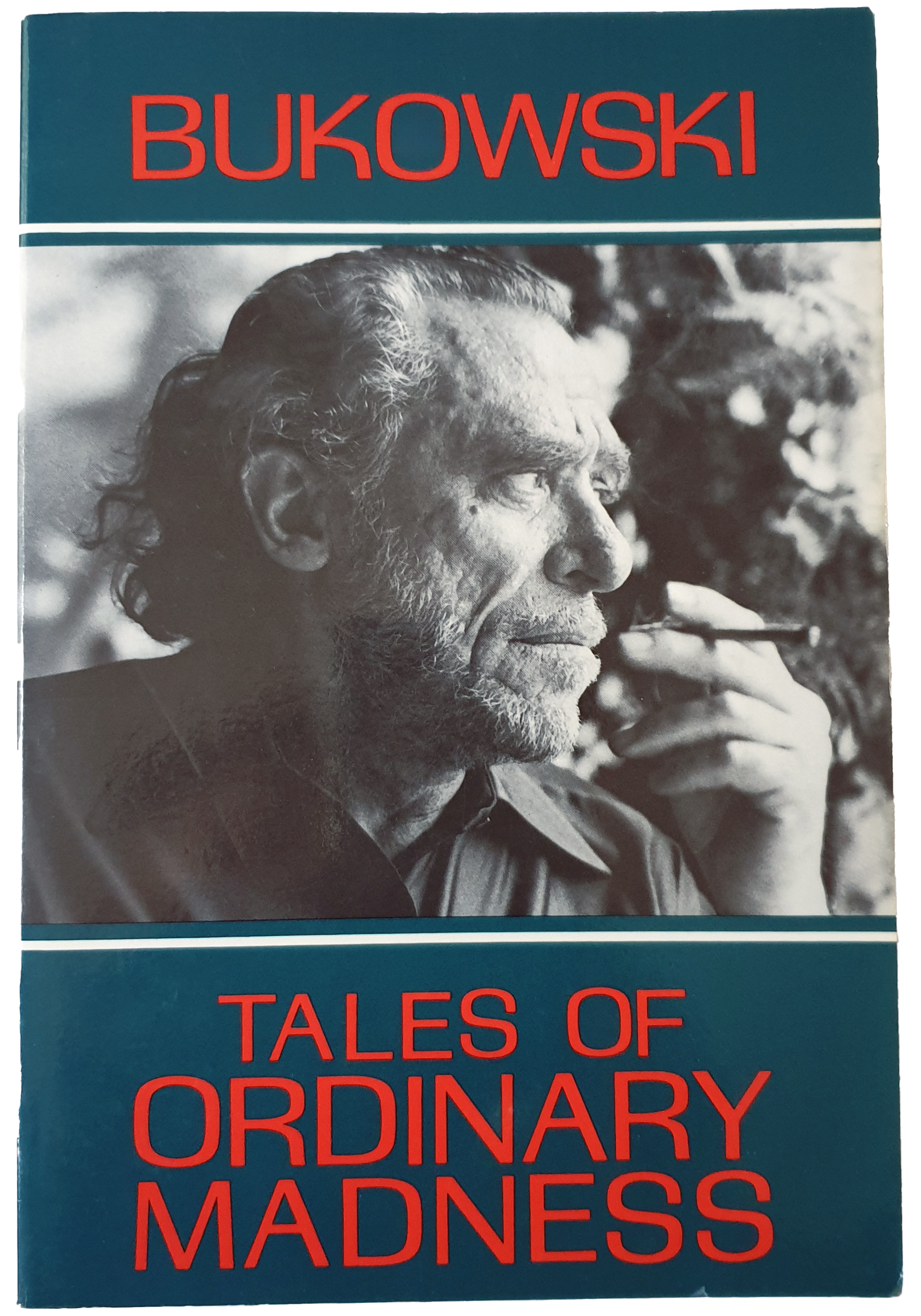

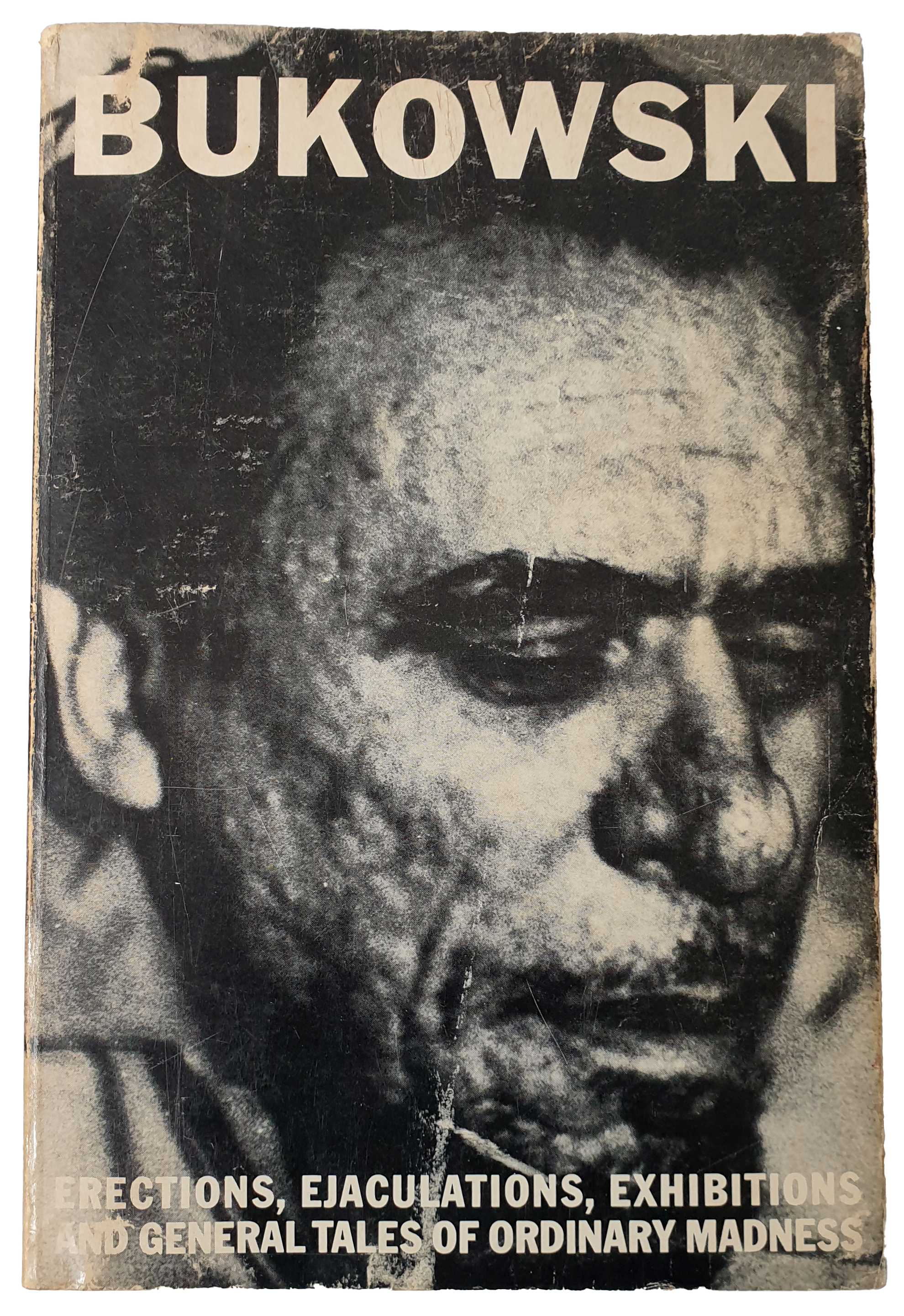

7. Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, City Lights (CL), April 1972 [reissued in two volumes in 1983]

7. Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, City Lights (CL), April 1972 [reissued in two volumes in 1983]

Bukowski at his most provocative: 500 pages full of grimy, sleazy, angst-ridden stories about necrophilia, pedophilia, and bizarre sexual encounters culled from the underground press and girlie magazines—the close-up photograph of an acne-disfigured Bukowski on the cover is foreboding enough. No wonder Martin, a committed Christian Scientist, passed on this, allowing Lawrence Ferlinghetti to champion Bukowski’s dirtiest persona. First titled Bukowskiana, featuring “the wildest shit since Bocaccio and Swift”, as Bukowski proudly said, this collection is like hearing W. C. Fields on paper, a joyous cocktail of shock-value material and entertaining musings on the human condition. Laughter through tears, as Gogol would say. Marty Balin of the Jefferson Airplane approached Bukowski with a finished movie script based on Erections, but the project didn’t happen. Storie di Ordinaria Follia, shot by Italian cult director Marco Ferreri, was released in 1981 to mixed reviews. Essential: “The Great Zen Wedding,” “Six Inches,” “The Fuck Machine,” “Life and Death in the Charity Ward,” “The Copulating Mermaid…,” “The Fiend,” “Animal Crackers in My Soup” (Bukowski’s favorite).

happen. Storie di Ordinaria Follia, shot by Italian cult director Marco Ferreri, was released in 1981 to mixed reviews. Essential: “The Great Zen Wedding,” “Six Inches,” “The Fuck Machine,” “Life and Death in the Charity Ward,” “The Copulating Mermaid…,” “The Fiend,” “Animal Crackers in My Soup” (Bukowski’s favorite).

.

8. Mockingbird Wish Me Luck, BSP, June 1972

8. Mockingbird Wish Me Luck, BSP, June 1972

As good as Bukowski ever got, up there with The Days Run Away. As Martin put it, “it’s one of my favorite books, it’s like a flash of lighting, pure and perfect.” A slim volume with high-octane poems—recently written for the most part—with shorter lines than usual and Bukowski treading into more narrative territory quite nonchalantly. So much so that a critic claimed that “he’s technical to the point of making you think he has no craft at all.” Bukowski in a state of grace. Essential: “The Mockingbird,” “Rain,” “Style,” “Those Sons of Bitches,” “The Shoelace,” “Another Academy,” “If We Take” (“and then, / love again / like a streetcar turning the corner / on time”).

.

9. South of No-North, BSP, 1973

9. South of No-North, BSP, 1973

Much like Erections, this is a collection of stories taken from the underground press and the erotic outlets. After the success of Post Office, Martin knew for a fact that prose sold substantially better than poetry, so he picked Bukowski’s tamer stories in an attempt to reach a wider audience. Bukowski’s lowlife affinities are matter-of-factly spelled out in “Guts”: “I have always admired the villain, the outlaw, the son of a bitch. I don’t like the clean-shaven boy with the necktie and the good job. I like desperate men, men with broken teeth and broken minds and broken ways . . . I don’t like laws, morals, religions, rules. I don’t like to be shaped by society.” Although reception was generally encouraging, Margins magazine published a negative review with a black border around the text, as if it were an obituary, and soon enough the rumor spread that Bukowski was dead. Essential: “Maja Thurup,” “This Is What Killed Dylan Thomas,” “All the Assholes…,” “Confessions…,” The Way the Dead Love.

.

10. Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame, BSP, 1974

10. Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame, BSP, 1974

Martin rescued here the best poems from It Catches, Crucifix, At Terror Street, and included a few recent efforts as well as an introduction by Bukowski himself. The new poems in the last section are a far cry from the early surrealist, lyrical style, with a clear focus on narrative, dialogue and Bukowski’s immediate reality. To many, a must-have. Essential: “The Trash Men,” “Trouble With Spain,” “The Fisherman,” “Some People” (“some people never go crazy. / what truly horrible lives / they must lead”).

.

11. Factotum, BSP, 1975

11. Factotum, BSP, 1975

Partly funded with a $5,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Factotum reads like a series of short-stories woven together by a disarmingly simple—yet fascinating—use of language. Bukowski chronicles Chinaski’s tour-de-force of his years on the bum, being unceremoniously fired from job after job. Never losing his sense of humor, Bukowski displays in no uncertain terms his aversion to the American nine-to-five work ethic, which, according to the New York Times Book Review, made him “closer to a prophet than to a crank.” A twentieth-century picaresque anti-hero novel. Factotum, directed by Bent Hamer and starring Matt Dillon, fell through the cracks in 2005. Essential: The blinds episode and the Wilbur Oxnard story.

.

12. Love Is a Dog from Hell, BSP, 1977

12. Love Is a Dog from Hell, BSP, 1977

Bukowski hit the big time after a major profile on him appeared in Rolling Stone in 1976, making him well-known outside the small press circles. Among other tidbits, readers were told that he was W.C. Fields “reincarnated as a writer” and that he learned cunnilingus at fifty. This collection—the first one entirely made up of new poems—was a reflection of Bukowski’s liberated, Dionysian times in the 1970s. In line with the final section in Burning in Water, the poems were less lyrical and more narrative and sexually-oriented. Not surprisingly, it became BSP’s poetry best-seller, and it was made even more popular by a transfixed rendition of “The Crunch” by Bono in the 2003 documentary Born Into This. Essential: “One for the Shoeshine Man,” “An Almost Made up Poem,” “Who in the Hell is Tom Jones?,” “Alone with Everybody,” “The Crunch” (“our educational system tells us / that we can all be / big-ass winners // it hasn’t told us / about the gutters / or the suicides”).

.

13. Women, BSP, 1978

13. Women, BSP, 1978

Despite some unfortunate editing choices by Martin, Bukowski was so satisfied with Women that he said it was “going to be the book. Riots in the streets and etc.” Although most reviewers corroborated it was his best writing to date, some sectors took Bukowski to task for a handful of passages they found downright offensive to women, calling him a male-chauvinist pig and worse. The self-deprecating humor of Bukowski’s sexual exploits and misfortunes with several women who clearly had the upper hand, making him look like a hopeless dummy at times, turned the book into an instant hit since the 8,000 copies of the first printing were sold out in thirty days, eventually making Women BSP’s prose best-seller. Paul Verhoeven of Basic Instinct fame was rumored to direct the film version, but it never happened. Essential: the dialogue throughout, and his now-popular take on drinking: “If something bad happens you drink in an attempt to forget; if something good happens you drink in order to celebrate; and if nothing happens you drink to make something happen.”

.

14. Play the Piano Drunk Like a Percussion Instrument Until Your Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit, BSP, July 1979

14. Play the Piano Drunk Like a Percussion Instrument Until Your Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit, BSP, July 1979

Slim, uneven collection with some old poems such as the classic “Fire Station” as well as all the poems printed in BSP’s Sparrow magazine. Bearing Bukowski’s longest book title ever, Play the Piano is not a particularly memorable volume. Bukowski himself acknowledged as much, saying “there was a certain verve and gamble missing… and there was a lot of repeat stuff.” Essential: “A Radio With Guts,” “Art,” “Fire Station,” “The Proud Thin Dying,” “Hug the Dark,” “Face of a Political Candidate on a Street Billboard.”

.

15. Shakespeare Never Did This, CL, September 1979 [reissued by BSP in 1995 with 11 poems]

15. Shakespeare Never Did This, CL, September 1979 [reissued by BSP in 1995 with 11 poems]

Bukowski’s only travelogue, illustrated with Michael Montfort’s photographs. This new angle on writing chronicled his 1978 trip to Europe. Back in his homeland, he read to 1,200 people in Hamburg, and hundreds were turned away—future Nobel Prize winner Günter Grass had read in the same venue a few months before to 300 people only. In France, he infamously and drunkenly walked off the Apostrophes set, much to the astonishment of the distressed host of the show, Bernard Pivot. His books were sold out the next day. He was interviewed by all major European newspapers and literary magazines, hailing him as “the new saint of literature” and “the best thing that happened to America” since Faulkner, Hemingway, and Mailer. His rock-star status in Europe made him popular and wealthy there while remaining relatively unknown in the U. S. Essential: The Apostrophes episode, and meeting his uncle Heinrich in Andernach, where Bukowski had been born.

magazines, hailing him as “the new saint of literature” and “the best thing that happened to America” since Faulkner, Hemingway, and Mailer. His rock-star status in Europe made him popular and wealthy there while remaining relatively unknown in the U. S. Essential: The Apostrophes episode, and meeting his uncle Heinrich in Andernach, where Bukowski had been born.

.

16. Dangling in the Tournefortia, BSP, 1981

16. Dangling in the Tournefortia, BSP, 1981

Foreign royalties were so substantial that Bukowski had to invest his hard-earned money or give it away to the IRS. He moved to San Pedro in 1978 with his wife-to-be Linda Lee, where he bought a large two-story house with a pool, a jacuzzi and a Japanese garden, and this volume reflects his apparent domestic and financial stability—humorously so in some poems. Bukowski felt it was a strong collection as it “rings of the new and the wild and the playful,” but longtime German translator, agent, and friend Carl Weissner said it was his least favorite book. The obvious shift in style, with longer narrative poems and a more pervasive gentleness, could feel a bit of a let-down to some. Still, the New York Times Book Review praised its “ear-pleasing cadences, wit and perfect clarity.” Essential: “We’ve Got to Communicate,” “On the Hustle,” “The Secret of My Endurance,” “Contemporary Literature, I.”

.

17. Ham on Rye, BSP, 1982

17. Ham on Rye, BSP, 1982

Bukowski’s best novel by most accounts. As Martin recalled, “I had asked Hank to go back and write the story of his childhood. He said, ‘I can’t, I can’t relive all that shit.’ I kept encouraging him, and then he began. It’s my favorite Bukowski novel.” This bildungsroman, which was “harder and slower than the other novels,” as Bukowski noted, re-enacted his growing up in Los Angeles with humor, angst, and sadness, highlighting two life-changing discoveries, the power of writing (“that’s what they wanted: lies. Beautiful lies . . . It was going to be easy for me”) and alcohol (“never had I felt so good. It was better than masturbating. It was magic”). Bukowski, shot in 2013 by actor/director James Franco, with an unsanctioned script by Adam Rager based on Ham on Rye, remains in limbo. Essential: the magic of alcohol and writing, and the Nazi trip.

.

18. Hot Water Music, BSP, September 1983

18. Hot Water Music, BSP, September 1983

Much like South of No North, this is a collection of stories first published in the underground press in the 1970s as well as new material printed in periodicals such as High Times. Bukowski was satisfied with the selection, saying “these things are entertaining, they get it done briskly and to the mark.” His favorite story was “The Man Who Loved Elevators.” Essential: “The Death of the Father,” “Fooling Marie,” “You Kissed Lilly”, “How to Get Published” (“genius might be the ability to say a profound thing in a simple way”).

.

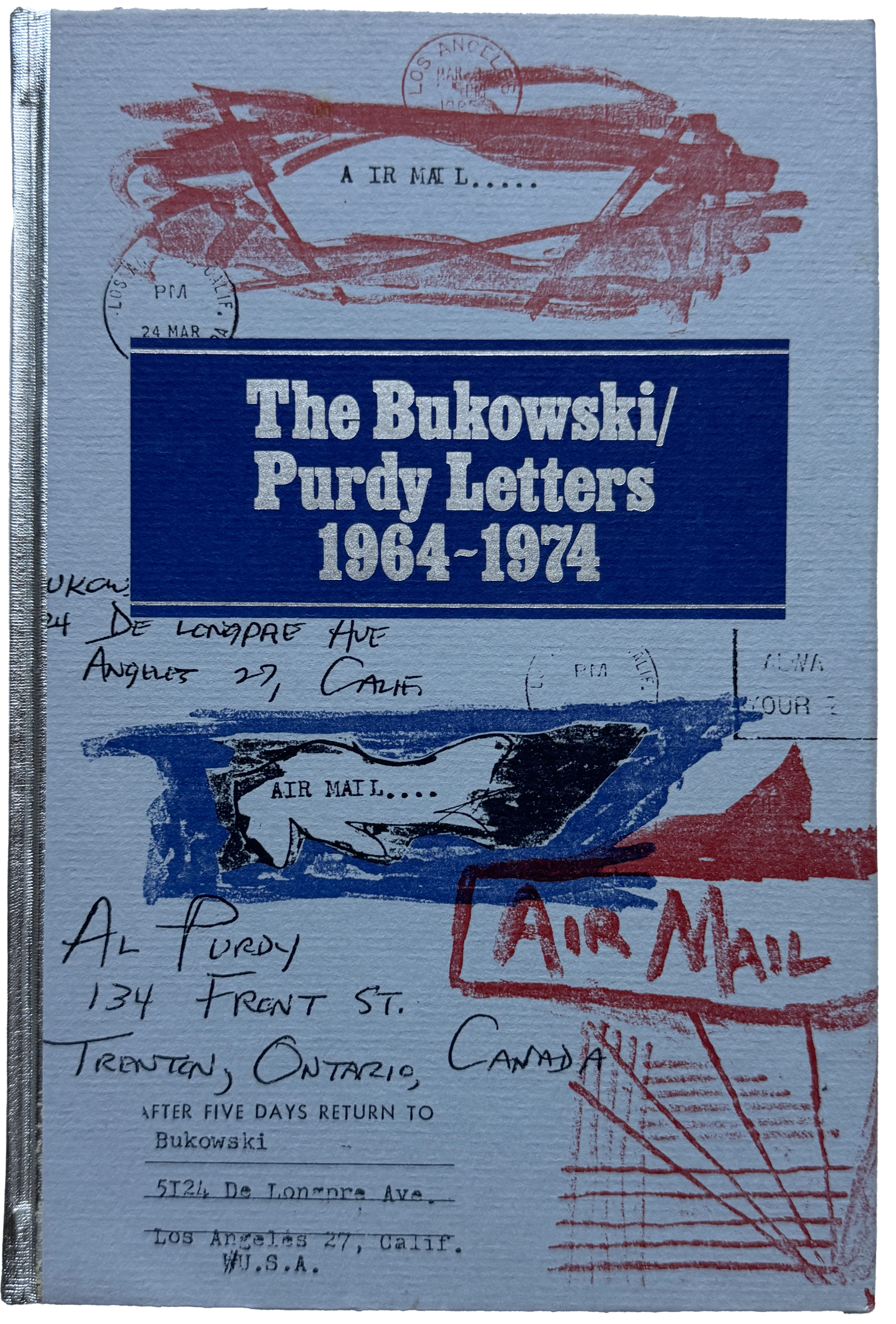

19. The Bukowski/Purdy Letters, 1964-1974, The Paget Press, November 1983

19. The Bukowski/Purdy Letters, 1964-1974, The Paget Press, November 1983

Book of correspondence with Canadian poet Al Purdy, edited by Seamus Cooney. The Paget Press was run by Peter Brown, who was BSP’s Canadian distributor. As Martin recalled, “he gave our print shop in Santa Barbara a great Heidelberg offset printing press. As a ‘thank you,’ I allowed him to publish The Bukowski-Purdy Letters and the first edition of Barfly.” Featuring a great deal of shop talk, reviewers noted that Bukowski came off as funny and Purdy as a humorless bore. Brown claimed that it “was met with a certain degree of fanfare. Independent booksellers throughout Canada devoted their main street shop windows to displays of the books.” Quite remarkable for a book of letters addressed to a small audience. Essential: the comments on other writers and Bukowski’s drawings.

.

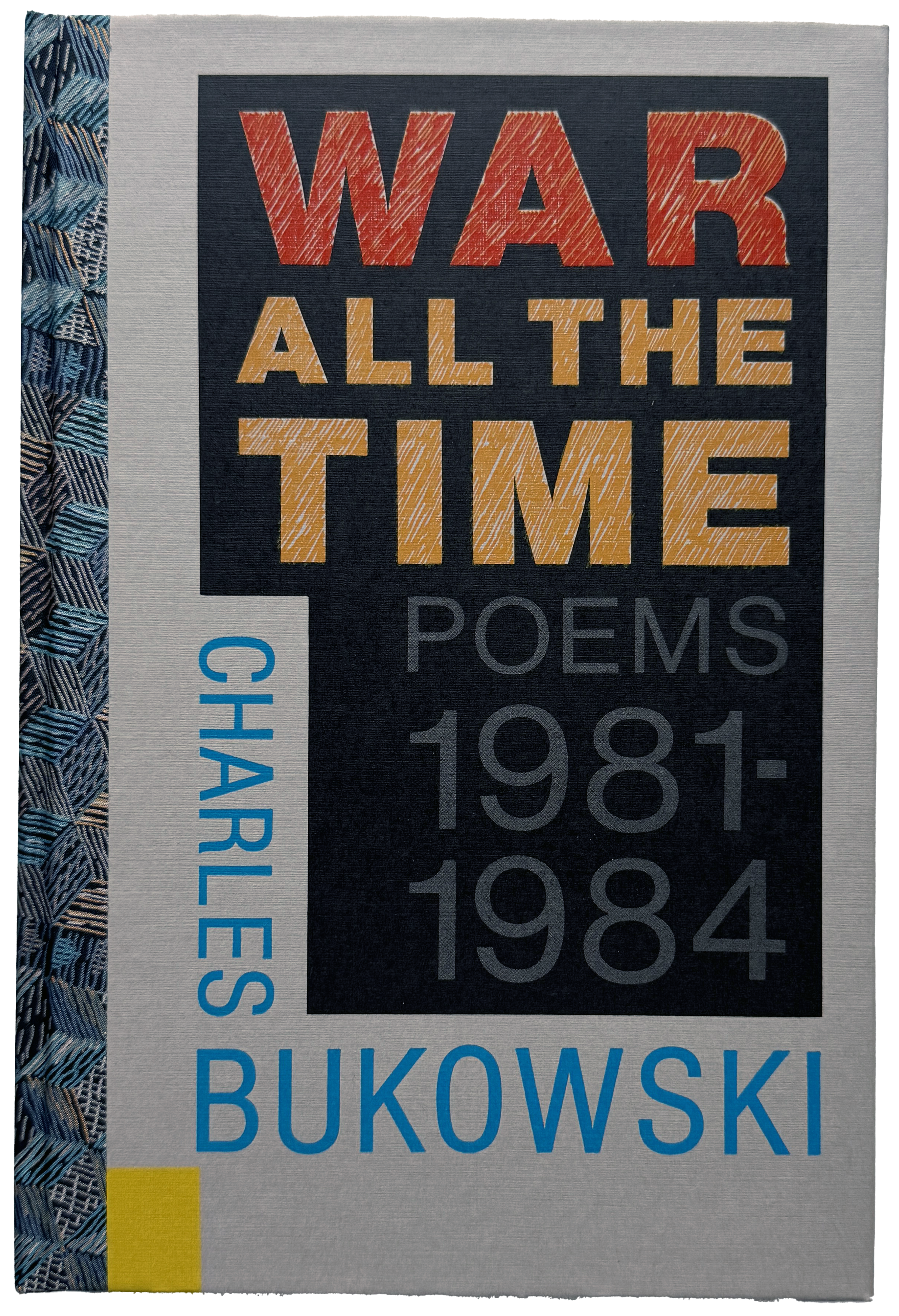

20. War All the Time, BSP, November 1984

20. War All the Time, BSP, November 1984

In line with Dangling, this collection contains a large number of long narrative poems. As a critic remarked, “while others debated how best to restore dramatic structures to verse, Bukowski just sat down and did it,” adding that “his best poems are often the longest. To quote a line here and there makes as much sense as to tell a punch line without the build-up.” Most poems in this collection—with Bukowski’s trademark humor—call for a laid-back approach, especially to enjoy his nostalgic take on dead authors, cats, and art, tinged with pain, cynicism, and, surprisingly enough, optimism. Essential: “The History of a Tough Motherfucker,” “Space Creatures,” “Sparks,” “Oh, Yes,” “Horsemeat,” “Eulogy to a Hell of a Dame.”

.

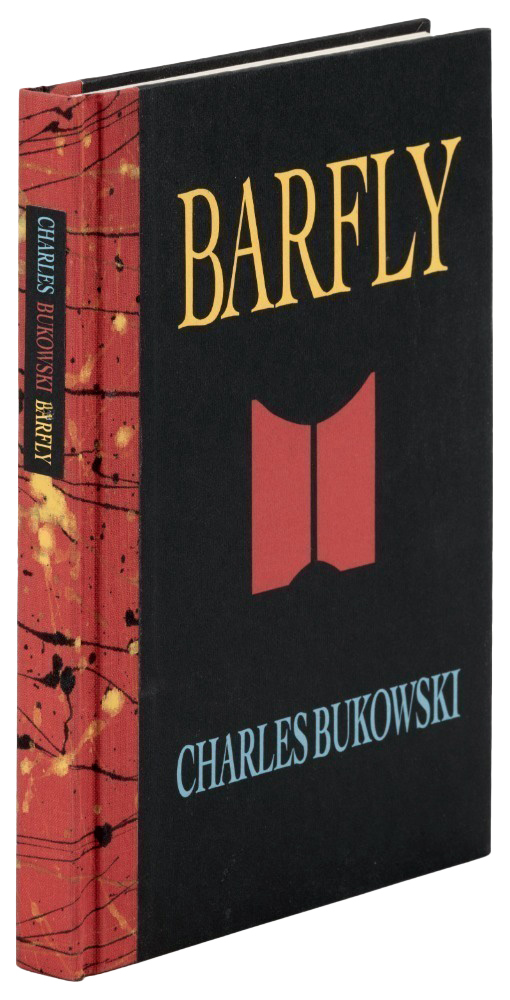

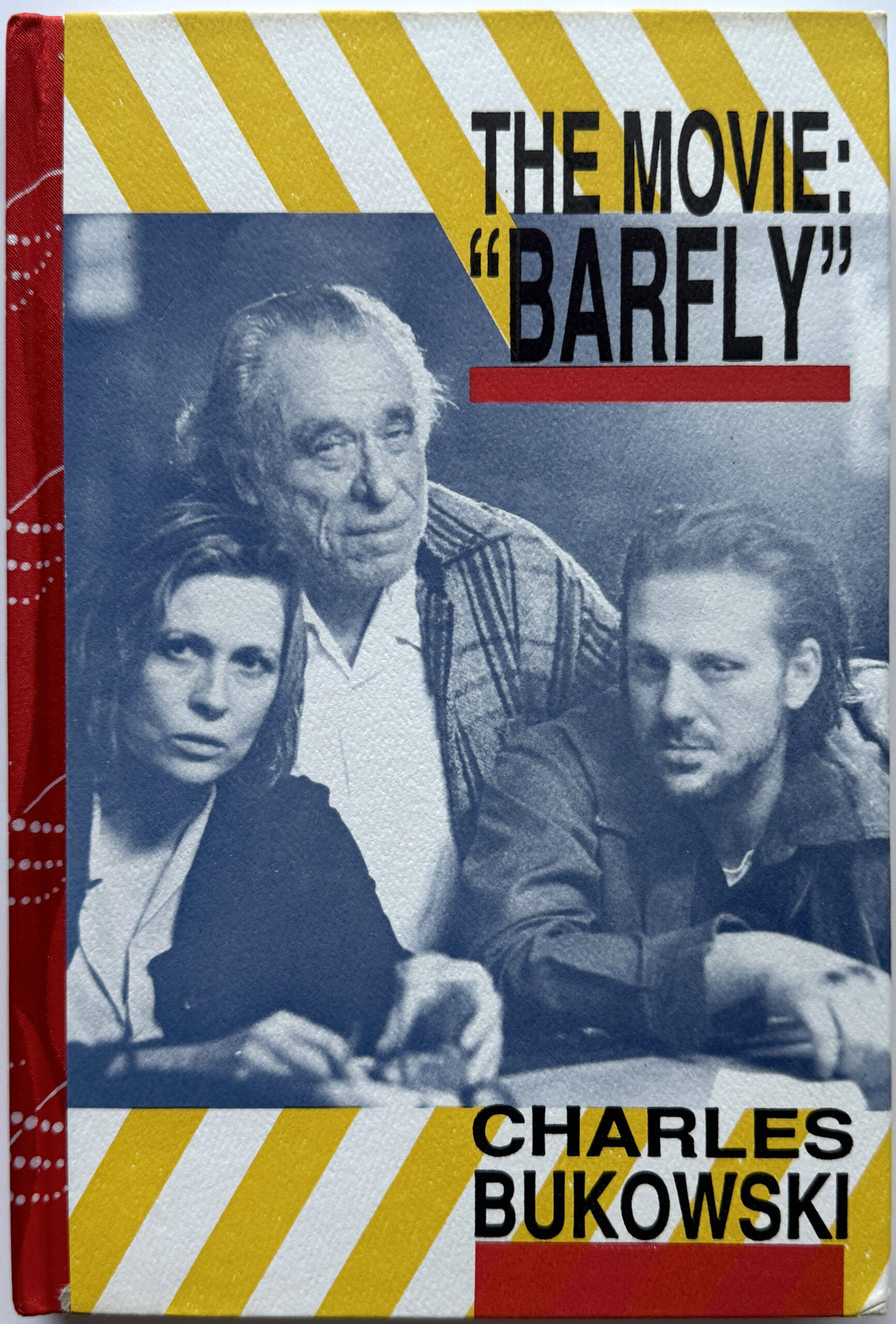

21. Barfly, The Paget Press, December 1984

21. Barfly, The Paget Press, December 1984

Bukowski’s only film script. Begun in 1979 and first titled The Rats of Thirst, it was commissioned by director Barbet Schroeder, who released Barfly in October 1987, starring Faye Dunaway and Mickey Rourke. The 1984 script contained some material, drawings and scenes that were not used in The Movie: Barfly, published by BSP in September 1987. Much to Bukowski’s astonishment, Schroeder wanted “a plot and an evolvement of character. Shit, my characters seldom evolve, they are too fucked-up.” Tender, dark, and wry, the story focused on three days in the life of the young Bukowski, which movie critic Roger Ebert saw as a “grimy comedy,” claiming it was one of the best movies in 1987. Shortly before, Time magazine had called Bukowski “the laureate of lowlife,” disclosing he was a bestseller in Europe and hardly known in the U. S. Barfly would dramatically change that perception—if only temporarily. Essential: the dialogue throughout, the corn scene.

too fucked-up.” Tender, dark, and wry, the story focused on three days in the life of the young Bukowski, which movie critic Roger Ebert saw as a “grimy comedy,” claiming it was one of the best movies in 1987. Shortly before, Time magazine had called Bukowski “the laureate of lowlife,” disclosing he was a bestseller in Europe and hardly known in the U. S. Barfly would dramatically change that perception—if only temporarily. Essential: the dialogue throughout, the corn scene.

.

22. You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense, BSP, 1986

22. You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense, BSP, 1986

The long, narrative lines in War All the Time gave way here to a more sparse writing style, with short, lean lines. Once again, Bukowski found Martin’s selection strong enough for publication, “a good mix of humor and despair.” As Bukowski got older, a sense of acceptance and gratitude began to permeate his work; his tone became more gentle and his outlook not so tough, softening his otherwise macho voice. Essential: “Beasts Bounding Through Time,” “No Help for That,” “Putrefaction,” “A Magician, Gone,” “Retired,” “Cornered.”

.

23. The Roominghouse Madrigals, BSP, 1988

23. The Roominghouse Madrigals, BSP, 1988

In a similar vein to The Days Run Away, this is a collection of poems culled from Bukowski’s early small press publications. With a clear reliance on metaphor rather than narrative, the overall tone is more lyrical than recent efforts. Martin noted that Bukowski “had a hard time coming up with a book title but at the last moment he called me and said, ‘I’ve got it! It’s The Roominghouse Madrigals!’ As always, he was great with titles.” Comparisons with The Days Run Away were largely unfavorable. Essential: “The Genius of the Crowd,” “Destroying Beauty,” “Layover,” “The Loser,” “The Blackbirds Are Rough Today,” “The Best Way to Get Famous Is to Run Away.”

.

24. Hollywood, BSP, 1989

24. Hollywood, BSP, 1989

The indomitable outsider was temporarily swallowed up by the ruthless Hollywood machinery. This novel is a satirical, elegiac account of the Barfly movie-making experience, written in a breezy staccato style that Bukowski defined as “pace, rhythm, dance.” Drink in hand, and with no arm-twisting at all, Bukowski took the chance to happily hang out with Madonna, Sean Penn, Norman Mailer, and other celebrities, but he soon found the limelight sickening and headed back to seclusion. He told Martin that he was looking forward “to the publication of Hollywood much more than the other novels. I think it’s because it’s such a laugher.” Most reviewers agreed it was one of his funniest books. Essential: François Racine and the chicken scenes, and Schroeder threatening the movie producers to cut his little finger off with an electric chainsaw if they didn’t bankroll the movie.

.

25. Septuagenarian Stew, BSP, 1990

25. Septuagenarian Stew, BSP, 1990

First collection to include both poetry and prose. Martin noted that Bukowski “liked the way the stories and poems played off against one another. Since he had just turned seventy, he called the book Septuagenarian Stew.” Many of the poems were written when Bukowski was down with tuberculosis and couldn’t drink as he was on antibiotics. The resulting clean, sparse lines, similar to You Get So Alone, proved he could deliver the goods even when sober. Essential: “The Life of a Bum,” “The Burning of the Dream,” “Bring Me Your Love,” “Gold in Your Eye,” “Rags, Bottles, Sacks,” “Hell Is a Lonely Place,” “Luck.”

.

26. The Last Night of the Earth Poems, BSP, 1992

26. The Last Night of the Earth Poems, BSP, 1992

Bukowski’s last poetry collection while alive—a late masterpiece on all counts. After receiving a Mac computer as a Christmas present in 1990, he doubled his already prolific output. He proudly told Martin that he was “running out of magazines to send to. Even some of the university publications are taking my things now.” The early angst was largely gone, replaced by elegiac, zen meditations on life. Like any other rock star, Bukowski had mellowed out, but he confronted death with his indelible humor, mischievously grinning like the Buddha statue he had at home. Martin concluded that it was “one of the most powerful and creative of Hank’s books. He could say twice as much in half the space. Hank’s last poems are like shafts of light that go straight to the heart.” Essential: “We Ain’t Got No Money…,” “Air and Light and Time and Space,” “The Bluebird,” “Flophouse,” “Dinosauria, We,” “Nirvana,” “The Word.”

.

27. Run with the Hunted, Harper Collins and BSP, May 1993

27. Run with the Hunted, Harper Collins and BSP, May 1993

Bukowski’s first anthology ever, released by mainstream publisher Harper Collins along with the customary BSP limited edition. Poignant selection, a top-notch primer for the unconverted. Chronologically arranged, featuring Bukowski’s most accomplished musings and banter on his favorite topics. As Martin recalled, he “loved telling Hank’s life story in his own words, using excerpts from novels, complete short stories and poems.” A no-holds-barred hagiography that helped Bukowski face leukemia—and death—with his head held up high.

arranged, featuring Bukowski’s most accomplished musings and banter on his favorite topics. As Martin recalled, he “loved telling Hank’s life story in his own words, using excerpts from novels, complete short stories and poems.” A no-holds-barred hagiography that helped Bukowski face leukemia—and death—with his head held up high.

.

28. Screams from the Balcony: Selected Letters 1960-1970, BSP, November 1993

28. Screams from the Balcony: Selected Letters 1960-1970, BSP, November 1993

Bukowski at his most honest, full of raw humanity, and stripped of any pretension. Screams is everything that The Bukowski/Purdy Letters wasn’t. A myth-debunker that showed that Bukowski wasn’t only, as Martin put it, “a hulking alcoholic genius getting into bar fights, getting drunk in alleys, rushing home at midnight to write great poetry. Here’s an educated, articulate, funny, very interesting man that many people have got wrong.” To Bukowski, writing letters was another outlet for his creativity. The ultimate misanthrope loved communication as much as anyone else. Essential: letters to the Webbs and Corrington.

.

29. Pulp, BSP, 1994

29. Pulp, BSP, 1994

Dedicated to “bad writing,” Bukowski finished it shortly before he died—against Linda’s will, he even signed with a trembling hand the “death sheets” for BSP’s limited editions. Begun in 1991, and rewritten in part several times, Bukowski felt he was tired of constantly talking about himself, and took a chance to explore new avenues. This giddy, gritty spoof of the hard-boiled detective novels—Chandler, Hammett, Spillane come to mind—was but a send-up and a send-off of himself as well as a tribute to Black Sparrow Press. Although it’s generally considered Bukowski’s worst novel, it was favorably reviewed in The New York Times and other major newspapers. Bukowski never saw a finished copy of this goodbye note, as he passed away while it was in press. Essential: the heartfelt ending, and the oft-quoted “it wasn’t my day. My week. My month. My year. My life. God damn it.”

.

30. Living on Luck: Selected Letters 1960s-1970s, BSP, 1995

30. Living on Luck: Selected Letters 1960s-1970s, BSP, 1995

Not as revealing as Screams, but it shone a light on Bukowski’s comings and goings in the 1970s—a third part of the book was made up of letters from the 1960s that were uncovered after Screams was published. As expected, Bukowski is seen attacking other writers, putting down most literature, passionately discussing his latest outpourings, and wryly commenting on his love-gone-wrong affairs. The overall feeling is summed up in a 1961 letter to Jon Webb: “Writing poems is not difficult; living them is.” Essential: letters to Carl Weissner, and the October 18, 1963 letter to Corrington where Bukowski discusses his now-famous motto “don’t try,” engraved on his tombstone.

.

31. Betting on the Muse, BSP, 1996

31. Betting on the Muse, BSP, 1996

Picking up on Septuagenarian Stew’s successful blend of poetry and prose, Betting is a collection of stories and poems that feels like a swan song. In 1994, Martin tried to hire Dorbin to put together a new book of poems culled off the little magazines—similarly to The Days Run Away and The Roominghouse Madrigals—but the project didn’t gel. Instead, Martin used part of a large selection he had already assembled in 1991. Posthumous edits, then, were largely innocuous. Essential: “The Laughing Heart,” “So Now?,” “What Happened to the Loving…,” “The Secret,” “Those Marvelous Lunches.”

.

31. Bone Palace Ballet, BSP, April 1997

31. Bone Palace Ballet, BSP, April 1997

Most of the poems here were taken from the same selection Martin put together in 1991, one of Bukowski’s most prolific years ever. The unusually metaphorical title, as Martin recalled, meant that Bukowski saw “the world as kind of a bone palace, beautiful on the outside, but filled with failure and the remains of those who had gone before on the inside.” The acceptance of death and old age prevails in many of the poems. Essential: “The Kenyon Review and Other Matters,” “First Love,” “The Strange Morning Outside the Bar.”

.

33. The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship, BSP, April 1997

33. The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship, BSP, April 1997

1991 was a unique year in Bukowski’s career. In addition to the customary deluge of poems, he began his most atypical novel, Pulp, and, prodded by editor/writer Jack Grapes, ventured into uncharted territory by trying the journal format. Martin collected most journal entries in The Captain, issuing a deluxe collector’s item in 1997 and the regular edition in 1998, both with art by Robert Crumb, who had already illustrated a few Bukowski short-stories. Sick with leukemia, Bukowski finished The Captain a year before he passed away, proving that despite the wise, mellow, hilarious undertones he still was a misanthropist with a mean streak, unafraid to experiment. Essential: the U2 concert, and yet another popular quotation: “We’re all going to die, all of us, what a circus! That alone should make us love each other but it doesn’t. We are terrorized and flattened by trivialities, we are eaten up by nothing.”

Bukowski short-stories. Sick with leukemia, Bukowski finished The Captain a year before he passed away, proving that despite the wise, mellow, hilarious undertones he still was a misanthropist with a mean streak, unafraid to experiment. Essential: the U2 concert, and yet another popular quotation: “We’re all going to die, all of us, what a circus! That alone should make us love each other but it doesn’t. We are terrorized and flattened by trivialities, we are eaten up by nothing.”

.

34. Reach for the Sun: Selected Letters 1978-1994, BSP, April 1999

34. Reach for the Sun: Selected Letters 1978-1994, BSP, April 1999

The final volume of correspondence provided an insightful look into Bukowski’s old age, still writing letters to dozens of young editors who were aching to print the celebrated Dirty Old Man musings in their emerging little magazines. A feeling of elated acceptance permeates most letters; Bukowski’s dealings with the much-dreaded popularity and old age’s setbacks—tuberculosis and leukemia—exude confidence rather than defeat. Endurance and perseverance kept him on a creative roll; despite the odds, he was unconditionally committed to his craft. Essential: letters to William Packard and John Martin, and the January 21, 1992 letter to Ivan Suvanjieff, which reads as a well-paced horror short-story.

.

35. What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire, BSP, October 1999

35. What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire, BSP, October 1999

First poetry collection put together by Martin after Bukowski’s passing: although the excruciatingly painful edits began here, Martin had hundreds of unpublished top-notch poems to choose from, making What Matters one of the strongest posthumous books. What Matters became well-known after seven billboards were put up for several months in Los Angeles displaying its title next to Bukowski’s name. As Martin recalled, “one man wrote to the L.A. Times, ‘I was driving to work. I was really depressed. My life was a mess. But when I saw that billboard, it gave me the courage to go on’.” Readers were empowered by “Roll the Dice,” too: “If you’re going to try, go all the / way. otherwise, don’t even start.” Essential: “A New War,” “Christmas Poem to a Man in Jail,” “To Lean Back into It.”

when I saw that billboard, it gave me the courage to go on’.” Readers were empowered by “Roll the Dice,” too: “If you’re going to try, go all the / way. otherwise, don’t even start.” Essential: “A New War,” “Christmas Poem to a Man in Jail,” “To Lean Back into It.”

.

36. Open All Night, BSP, 2000

36. Open All Night, BSP, 2000

While assembling this book, Martin drew upon an archive of some 450 poems that he had set aside for future collections. It’s brimming with mundane anecdotes, hilarious catalogs of others’ tribulations, and musings on drinking and existential misgivings. Sexual escapades are duly chronicled down to the last detail, too. What Matters and Open All Night set a pattern that soon became obvious in most posthumous volumes: overall, old poems were more accomplished than recent efforts. Essential: “Dinner, Pain & Transport,” “Beauty Gone,” “The Death of an Era.”

.

37. Beerspit Night and Cursing: The Correspondence of Charles Bukowski and Sheri Martinelli 1960-1967, BSP, April 2001

37. Beerspit Night and Cursing: The Correspondence of Charles Bukowski and Sheri Martinelli 1960-1967, BSP, April 2001

Lacking the overall punch of previous Bukowski-only correspondence volumes, partly due to Martinelli’s convoluted writing and Bukowski’s cringey attempt at flattering her by imitating her style rather unconvincingly, this collection reads like an epistolary novel where the dialogue is both tender and caustic, gripping and repelling. Martinelli was a protégé of Ezra Pound and Anaïs Nin, a talented painter, and a former Vogue model who was completely immersed in post-World War II bohemia. Editor Steven Moore claimed he “did the book because I was interested in Martinelli, not him.” Martin’s assessment also favored Martinelli’s “fascinating figure,” with Bukowski trying to match “his intellect and wit with hers.” Not surprisingly, Bukowski and Martinelli never met. Essential: the ruminations on cats and Ezra Pound, and the drawings at the end.

.

38. The Night Torn Mad with Footsteps, BSP, September 2001

38. The Night Torn Mad with Footsteps, BSP, September 2001

Last major Bukowski collection to be published by BSP. Shortly after, Martin closed up shop as he was “convinced that the independent publishing industry was on the verge of collapse. I would have continued, but right at that moment Harper Collins came to me and offered to buy the publication rights to Bukowski, Bowles, and Fante. It was a godsend.” Ordinary events are seen through Bukowski’s extraordinary lens, combining wit and cynicism, grittiness and the disputable wisdom of a suburbia Buddha. An uneasy been-there-done-that sense of déja vù begins to shine through these posthumous collections. Essential: “Wine Pulse,” “Carson McCullers,” “A Definition,” “The Condition Book,” “40 Years Ago.”

.

39. Sifting Through the Madness for the Word, the Line, the Way, Ecco, 2002

39. Sifting Through the Madness for the Word, the Line, the Way, Ecco, 2002

As part of the lucrative deal with Harper Collins, Martin was to edit the next five collections for Ecco. Selecting from a vast array of old and new material, Martin made “no attempt to print these poems in chronological order.” Rather, they appear thematically grouped, introducing a gentler, mellower Bukowski, with the occasional display of toughness and grittiness to keep hardcore fans happy. Storytelling and self-mockery make it easier to digest the heavily-edited prescriptive poems on horse-racing, drinking, misanthropy, and Bukowski’s womanizing persona. Essential: “So You Want to Be a Writer?,” “After the Sandstorm,” “Nobody but You.”

.

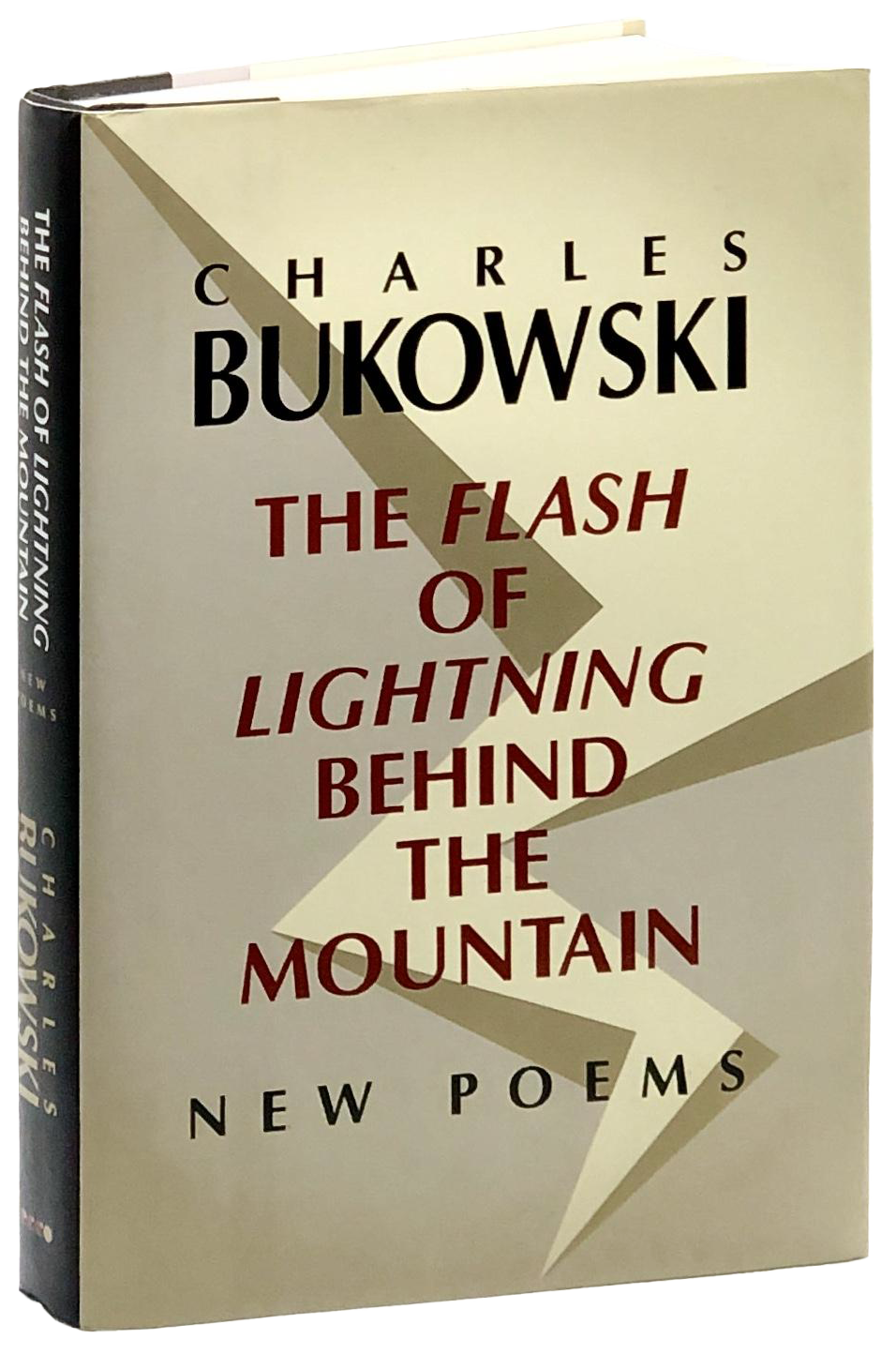

40. The Flash of Lightning Behind the Mountain, Ecco, 2003

40. The Flash of Lightning Behind the Mountain, Ecco, 2003

This volume could have been titled On Death, as many of the poems were written in 1993 and early 1994, barely a few weeks before Bukowski passed away. Despite the overbearing presence of death throughout, there are some unusual, welcome political references and a few clunkers saved by Bukowski’s undying sense of humor—the carte blanche for egregious editing became more evident as posthumous collections kept appearing, leading some reviewers and long-time fans to believe there was an un-Bukowskian whiff about them. Essential: “The Birds,” “A Visitor Complains,” “Cold Summer,” “One More Day.”

.

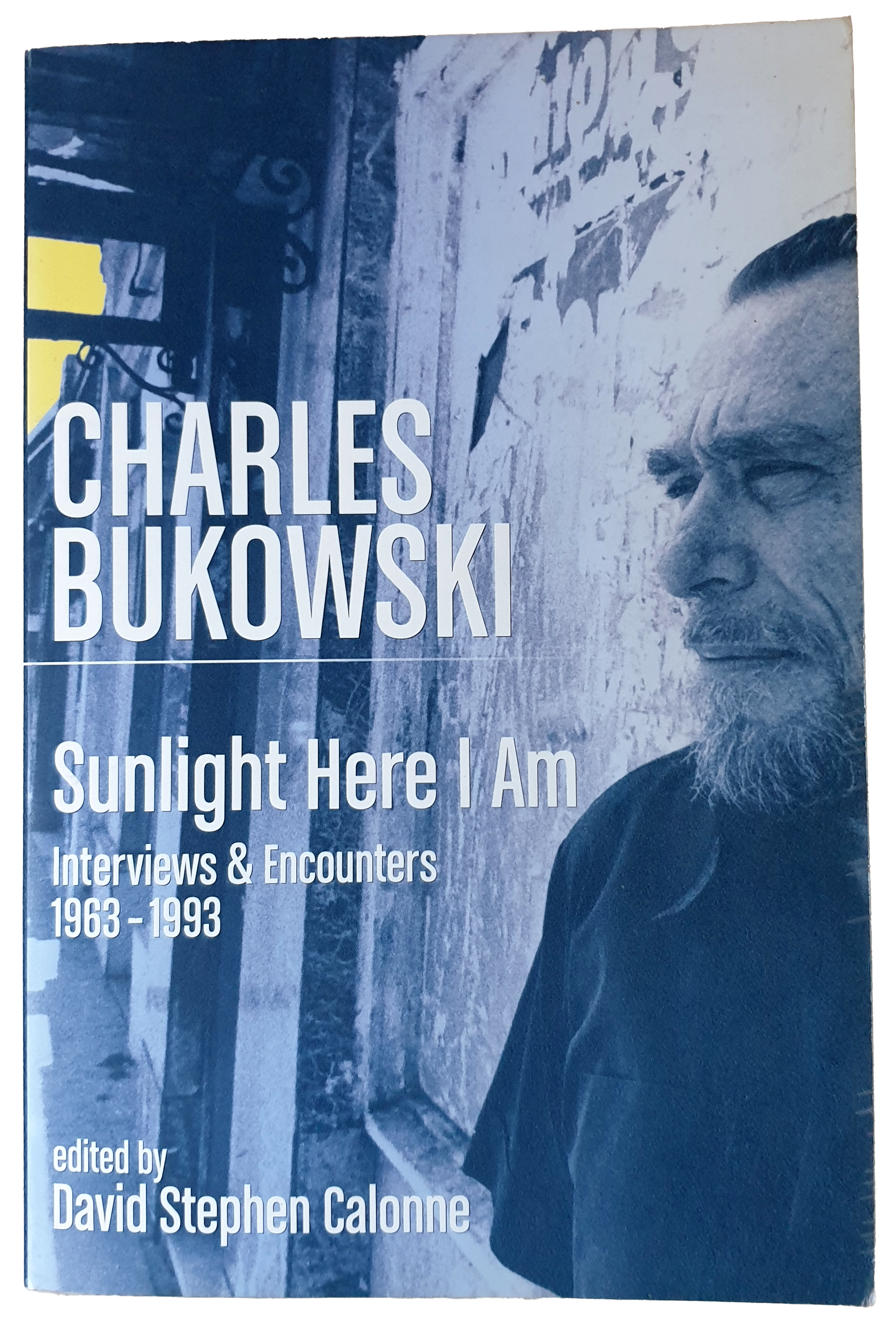

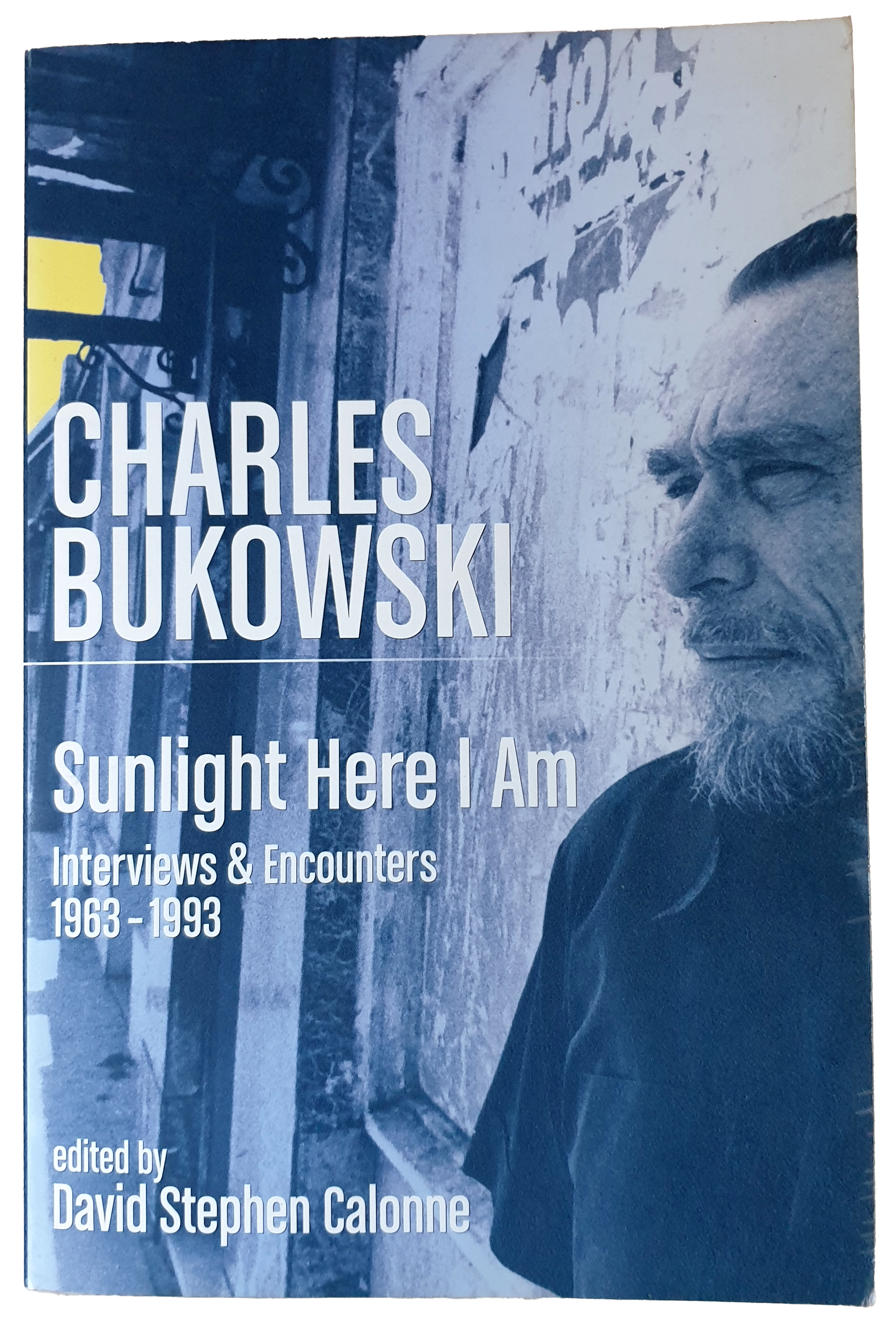

41. Sunlight Here I Am: Interviews & Encounters 1963-1993, Sun Dog Press, 2003

41. Sunlight Here I Am: Interviews & Encounters 1963-1993, Sun Dog Press, 2003

A revealing, different take on Bukowski. Editor David Calonne’s discerning selection makes for an insightful, gripping reading, including some nuggets such as a 1967 self-interview where Bukowski unabashedly maintains that the poetic scene is “dominated by soulless, lonely jackasses.” Calonne himself was astonished by the quality of most interviews: “The main discovery here was just how many good interviews Bukowski gave for a supposedly reclusive person.” Reception was so positive that Sunlight was translated into many languages, and the U. S. edition remains in print. Essential: “This Floundering Old Bastard…,” “Paying for Horses…”

.

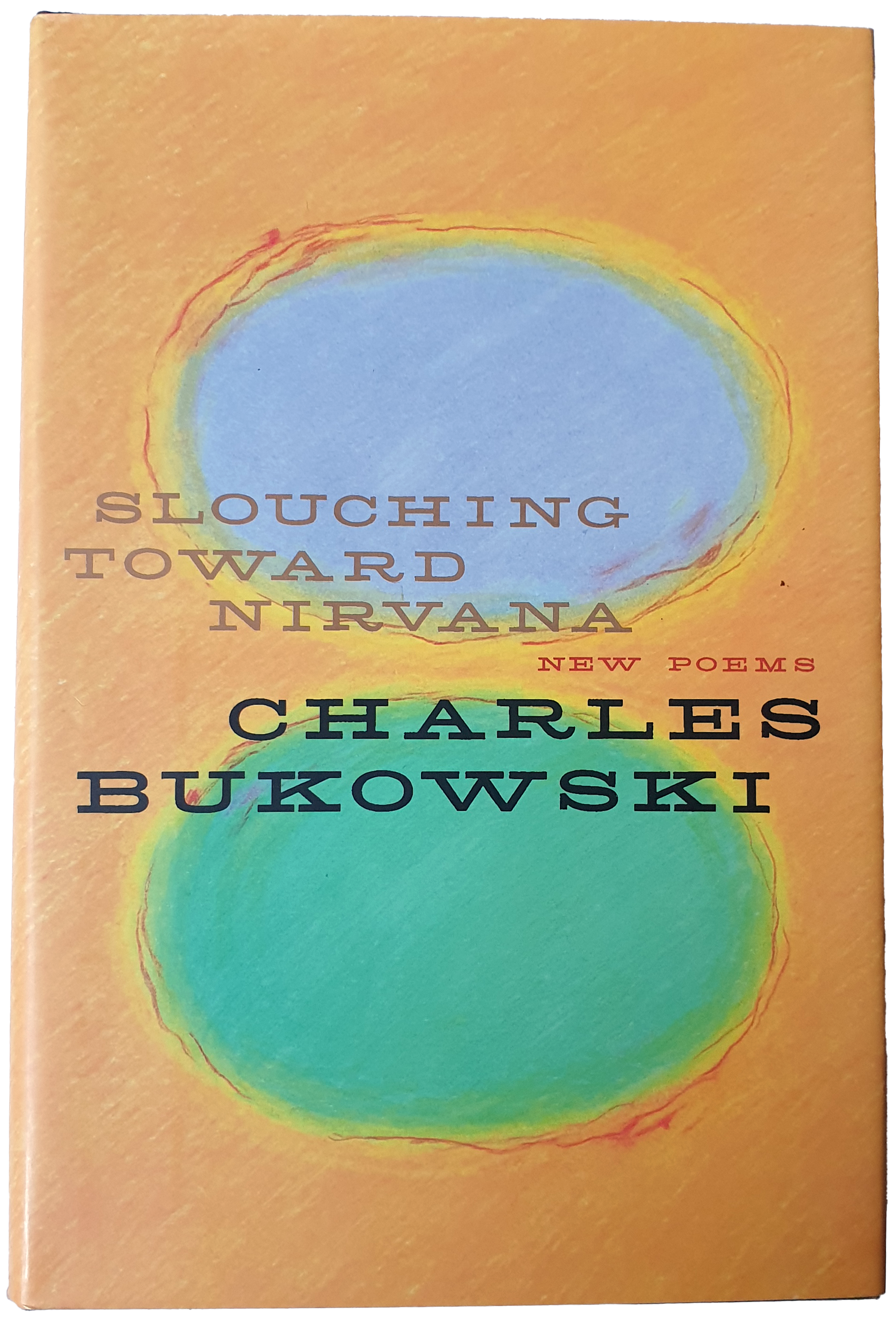

42. Slouching Toward Nirvana, Ecco, 2005

42. Slouching Toward Nirvana, Ecco, 2005

One of the weakest posthumous collections. Readers didn’t know most poems had been tampered with, concluding—wrongly so—that posthumous volumes were essentially made up of leftovers and substandard material. Bukowski’s trademark narrative, terse lines along with the philosophical, witty angle on ordinary matters, the unmistakable pace, and his uncanny ability to record things as he saw them, make up for the doctored poems. Essential: “The Wine That Roared,” “I Fought Them from the Moment I Saw Light,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.”

.

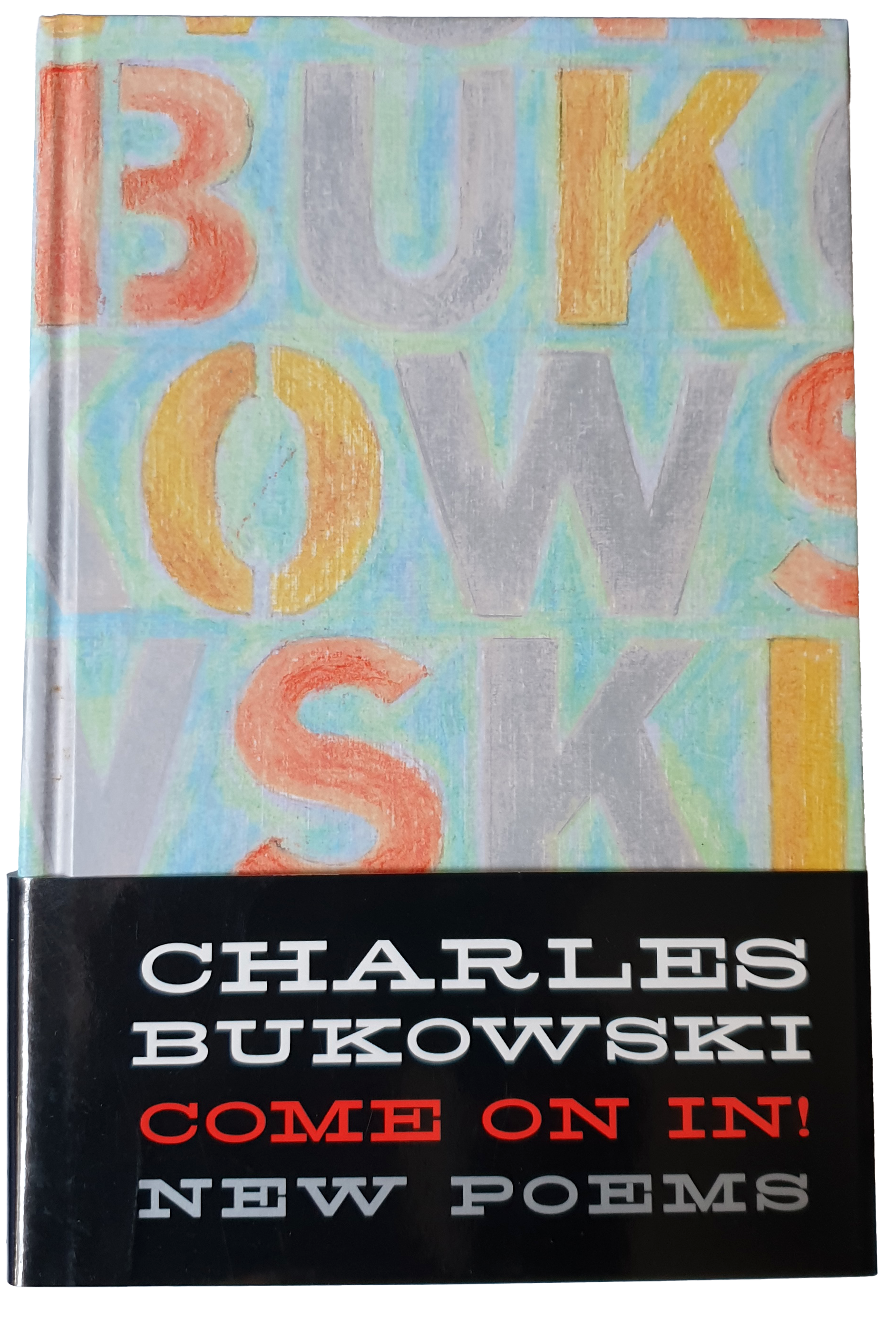

43. Come On In!, Ecco, 2006

43. Come On In!, Ecco, 2006

In June 2006, Bukowski’s papers were donated to the Huntington Library in San Marino, where they are now rubbing shoulders with the Ellesmere illuminated manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, a vellum copy of the Gutenberg Bible, and a life mask of William Blake. Forty-three years after the publication of It Catches—and forty-three books later—who would have guessed? Most poems deal with the ups and downs of the literary life as seen through Bukowski’s mellower, perennially artless lens. The New York Times review was right on the mark: “That his poems get an F for craft doesn’t bother him.” Proper craftsmanship and institutionalization never turned Bukowski on. Essential: “No Leaders, Please,” “My Cats,” “Mind and Heart.”

.

44. The People Look Like Flowers at Last, Ecco, March 2007

44. The People Look Like Flowers at Last, Ecco, March 2007

A large part of the poems here were culled from little magazine appearances, making this collection stronger than previous posthumous offerings. Despite its title, it’s anything but a flower-power paean to the human condition. Rather, it’s vintage Bukowski, a mordant, down-and-out, raffish, at times nostalgic trip down memory lane. While unapologetically trashing most literature, Bukowski surprises readers with some tender asides for his daughter Marina. Essential: “The Snow of Italy,” “Too Near the Slaughterhouse,” “The Dwarf with a Punch,” “Fog,” “Poem for My Daughter,” “I Never Bring My Wife.”

.

45. The Pleasures of the Damned, Ecco, October 2007

45. The Pleasures of the Damned, Ecco, October 2007

This anthology feels like a four-sided greatest hits album, with Bukowski’s finest thundering on and on. As Martin noted, “it reads like Shakespeare to me. 550 pages of great poems.” Reviewers were mostly elated with the 273-poem selection, too: The New York Times said Bukowski was “a gangster poet who made it to the canon through a secret back door,” while the Los Angeles Times claimed he was “a hit-or-miss talent.” The Washington Post found this collection crude and lyrical, tagging Bukowski as a “closet romantic” who “shocks you on one page and moves you on the next.” A timeless collection for both the uninitiated and the staunchest fan.

.

46. Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook, CL, 2008

46. Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook, CL, 2008

From here on out—with the exception of the next book—new collections were no longer subject to the awful edits that marred most posthumous volumes. After a three-decade break, City Lights resumed publishing Bukowski’s prose, unearthing some long-forgotten gems such as a handful of very early stories. Editor Calonne was bewildered to find that “Bukowski was a much-better read, and much more profoundly ‘cultured’ writer, than many of his detractors had supposed.” Reviewers saw it as a “rollercoaster ride” and a “mixed bag” featuring Bukowski’s trademark directness and no-holds-barred take on some topics readers found obscene, controversial, and morally depraved. Essential: “A Rambling Essay on Poetics…,” “Dirty Old Man Confesses,” “Aftermath of a Lengthy Rejection Slip.”

.

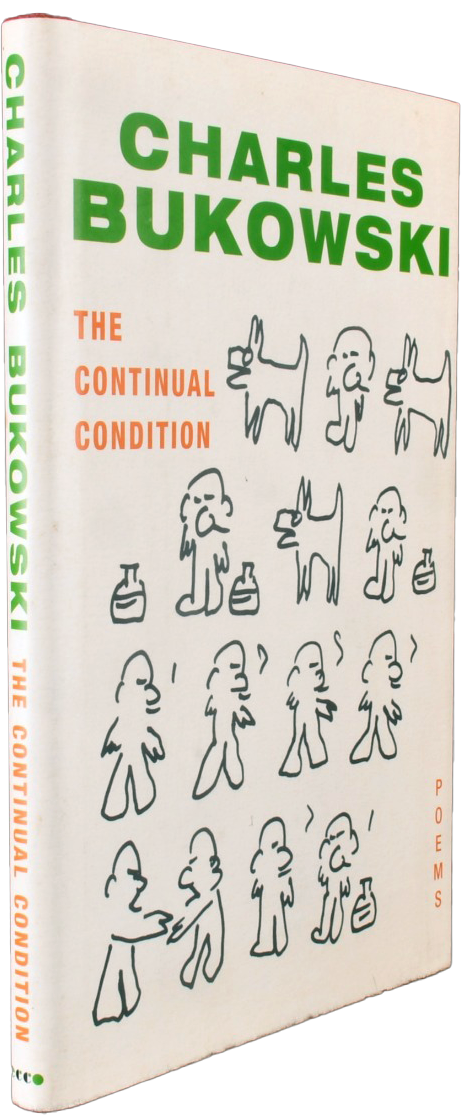

47. The Continual Condition, Ecco, 2009

47. The Continual Condition, Ecco, 2009

Make no mistake, this is the worst posthumous collection by a long shot. It’s a slim volume of subpar, heavily-edited poems. Not only that, twenty of the sixty-three poems were duplicates that had already been published by BSP and Ecco. To top it off, half-a-dozen poems that had been rightfully discarded from previous Ecco projects made it back here. By comparison, the uneven Play the Piano stands out as an all-time masterpiece. Sadly, this largely forgettable and unremarkable book was Martin’s swan song as Bukowski’s editor. Essential: “Bayonets in Candlelight” (still a highlight despite having lost sixty-seven of the original ninety-eight lines in the editing room), “I Saw a Tramp Last Night.”

.

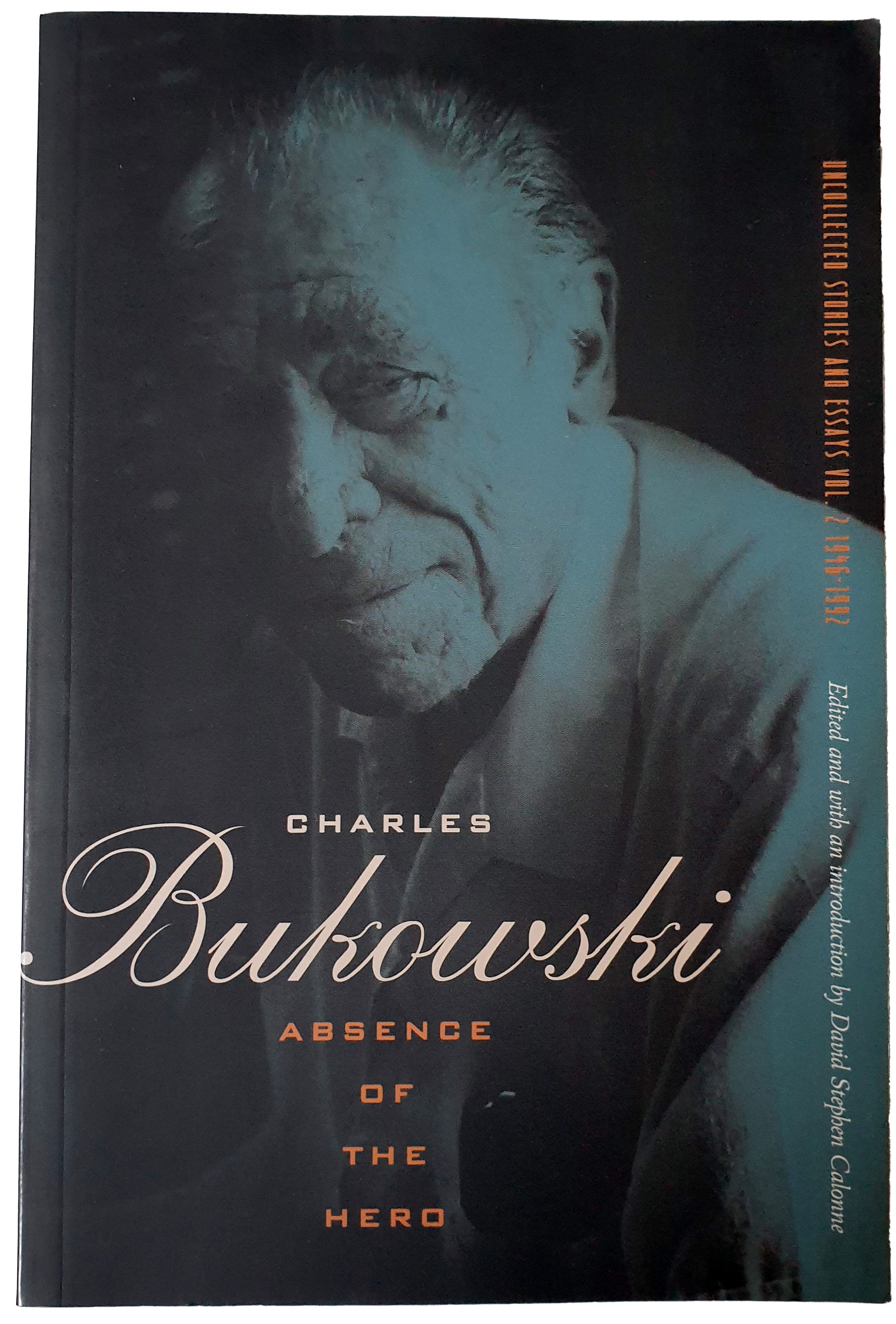

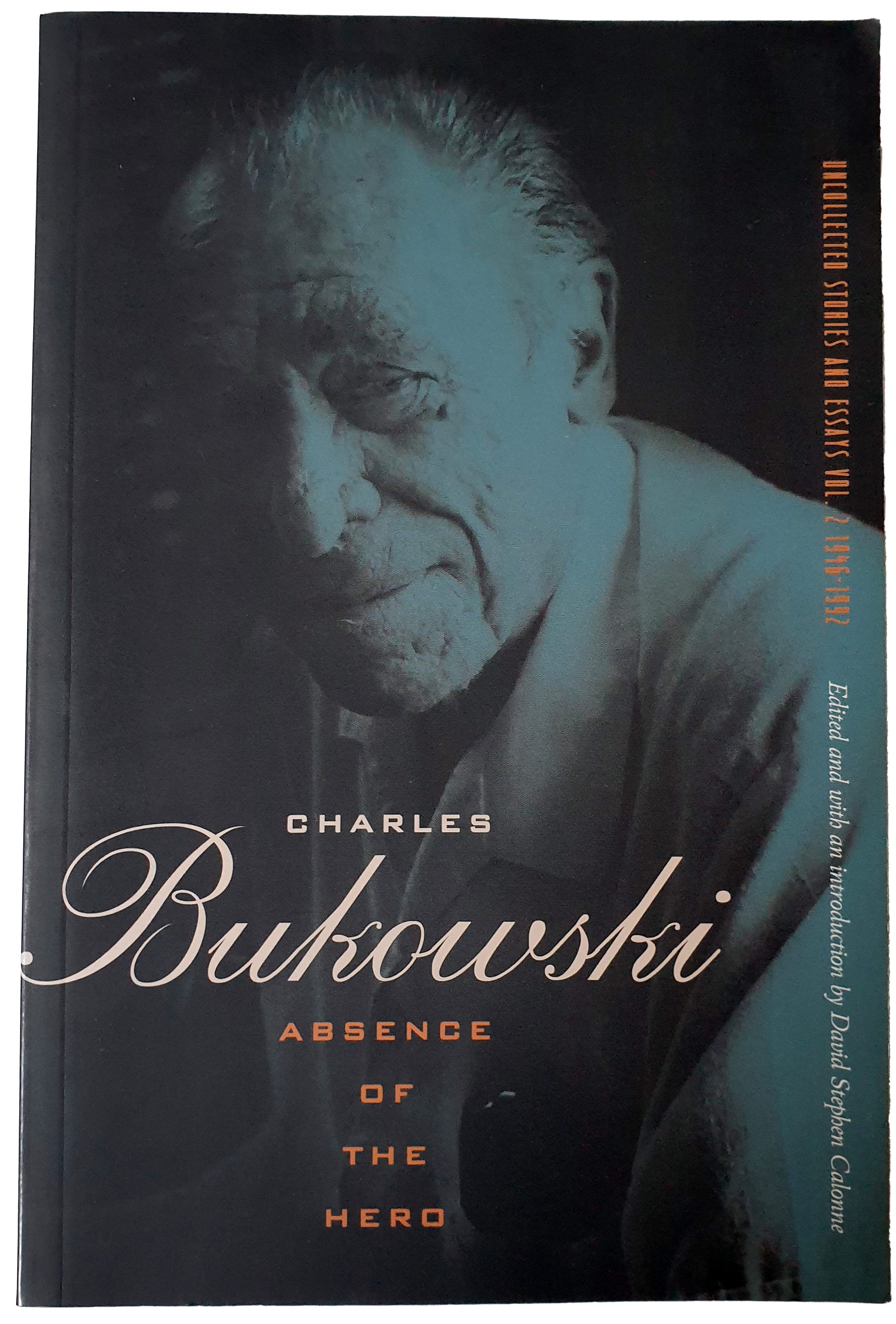

48. Absence of the Hero, CL, 2010

48. Absence of the Hero, CL, 2010

The “Charles Bukowski: Poet on the Edge” exhibit opened at the Huntington Library in October 2010 and ran until February 2011. Curator Sue Hodson, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, said Bukowski was “a writer for the common man.” In this new collection, Calonne tried to reflect that commonality as well as “Bukowski’s involvement with the Beat movement and his connection to the underground press.” The overall reflective tone, with flashes of hope throughout, was deemed “masterfully comic” by critics. Essential: “Cacoethes Scribendi,” “He Beats His Women,” “Christ with Barbecue Sauce” (first rejected by Playboy, Nola Express, and Ferlinghetti himself in the 1970s, Bukowski thought this story on cannibalism was a humorous masterpiece because it admitted “to all human possibilities without guilt”).

.

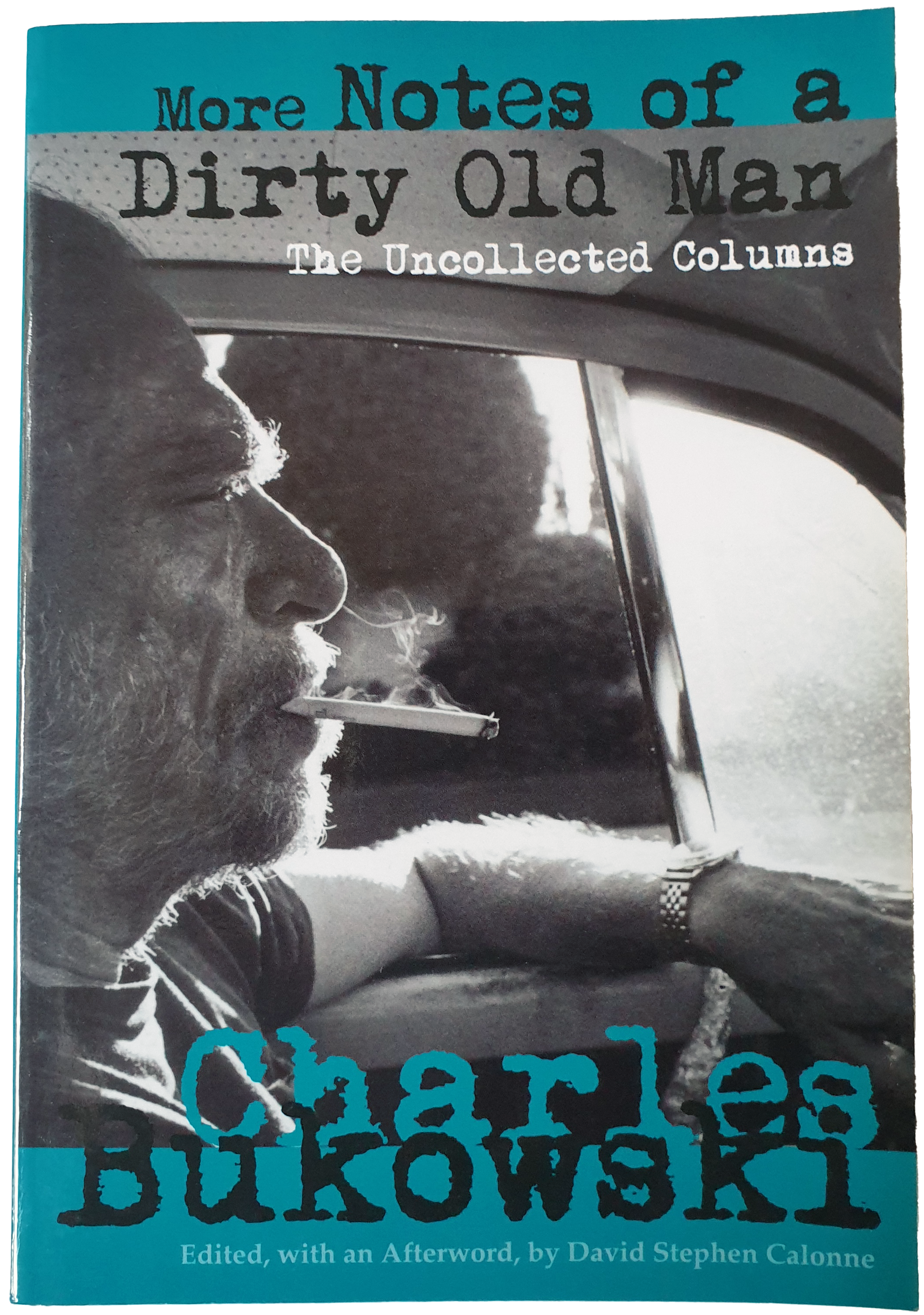

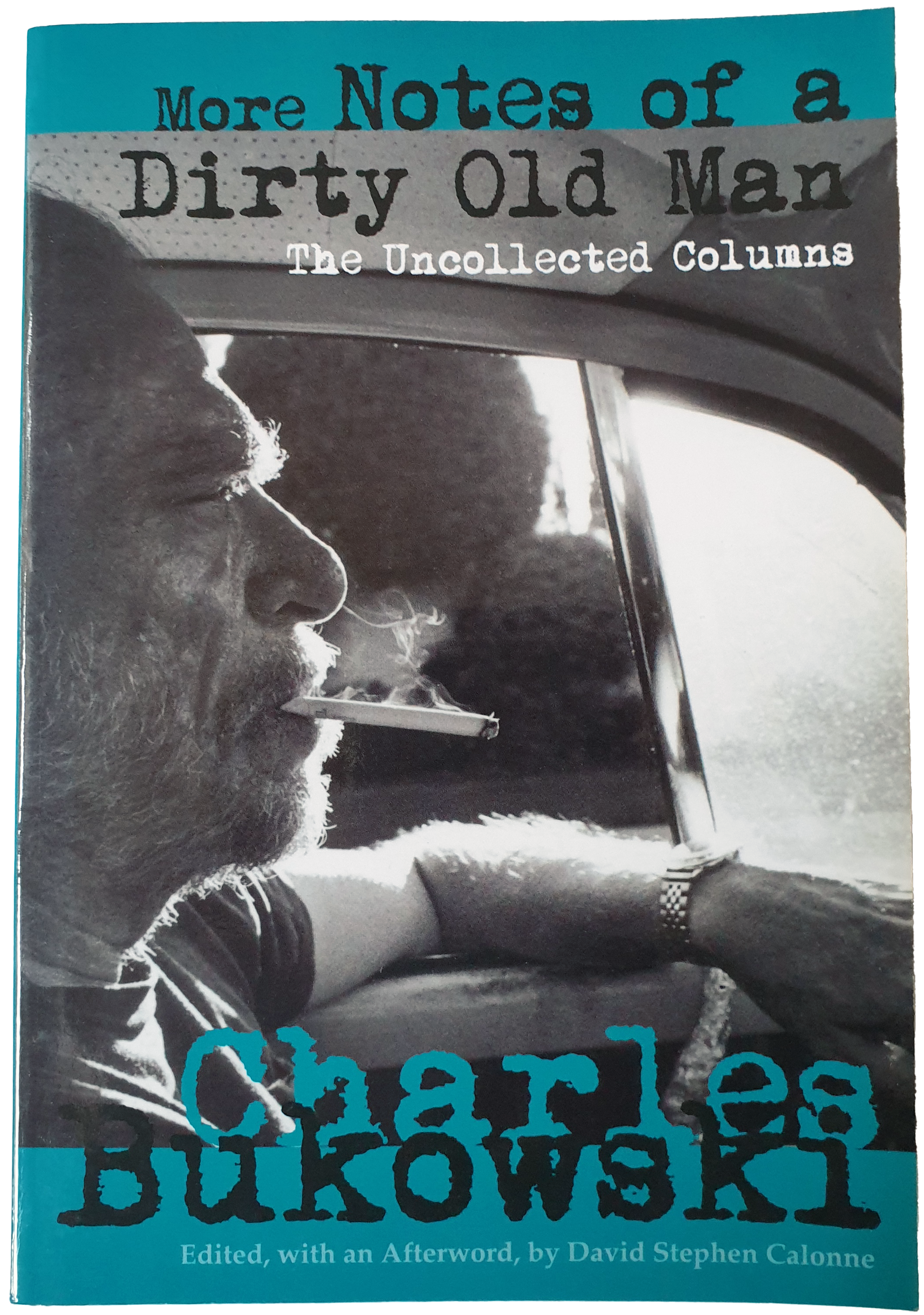

49. More Notes of a Dirty Old Man, CL, 2011

49. More Notes of a Dirty Old Man, CL, 2011

A guiltless, playful Bukowski emerges in most of the columns collected here, mercilessly ridiculing Flower Power ideology, recounting explicit sexual encounters, pondering about suicide, and poking fun at aggrieved readers. This time around, Calonne wanted to “to show the range of the various kinds of writing Bukowski submitted. I also explored the influence of the column on artists such as Tom Waits and Raymond Carver.” Vulgar, fearless, antiacademic, and hilarious, these columns remain as relevant and original as they were in the late 1960s and early 1970s in their attempt at shocking readers from all walks of life, liberals included. Essential: the column about visiting the Webbs in New Orleans, “My Friend, the Gambler.”

.

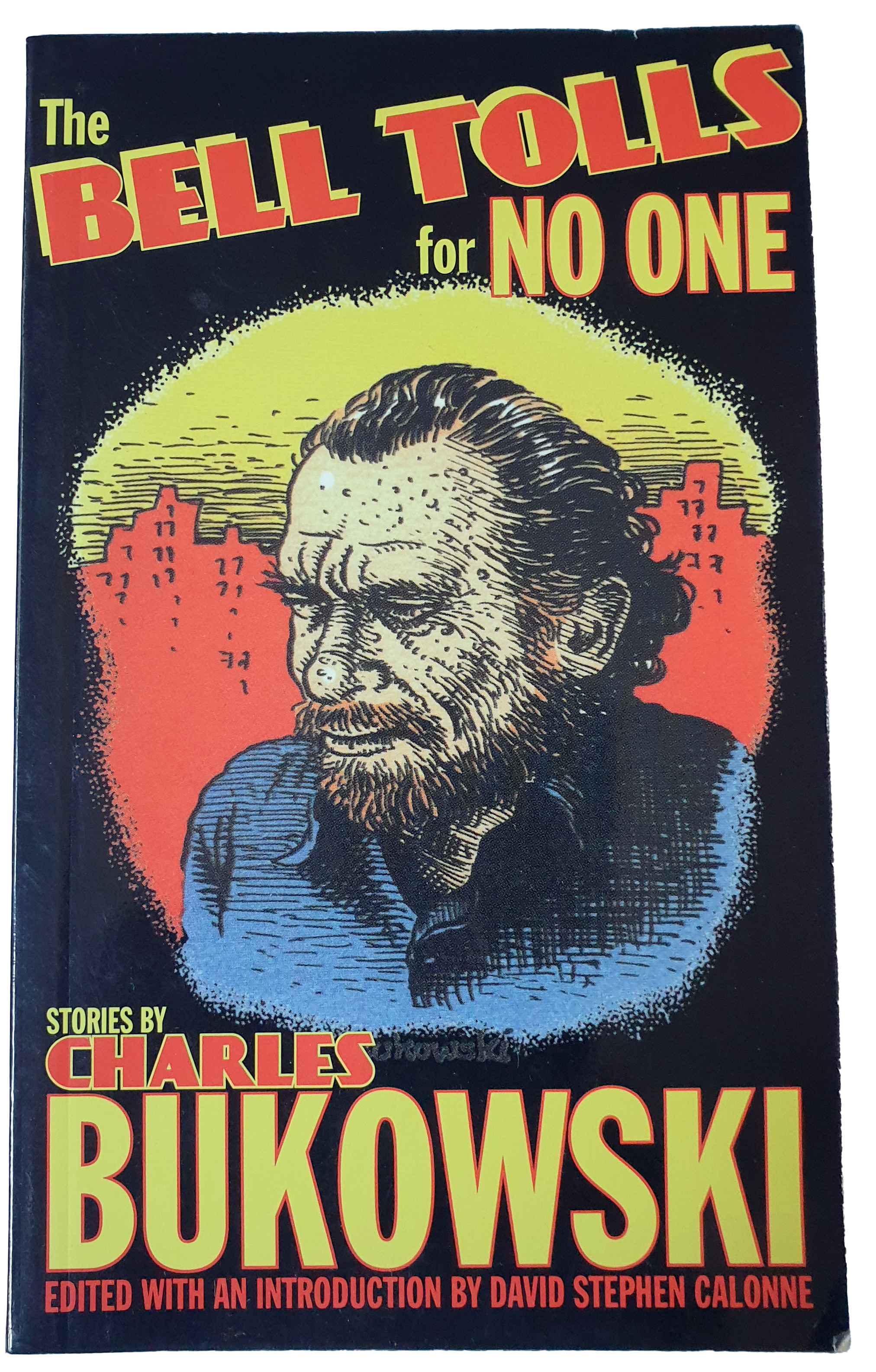

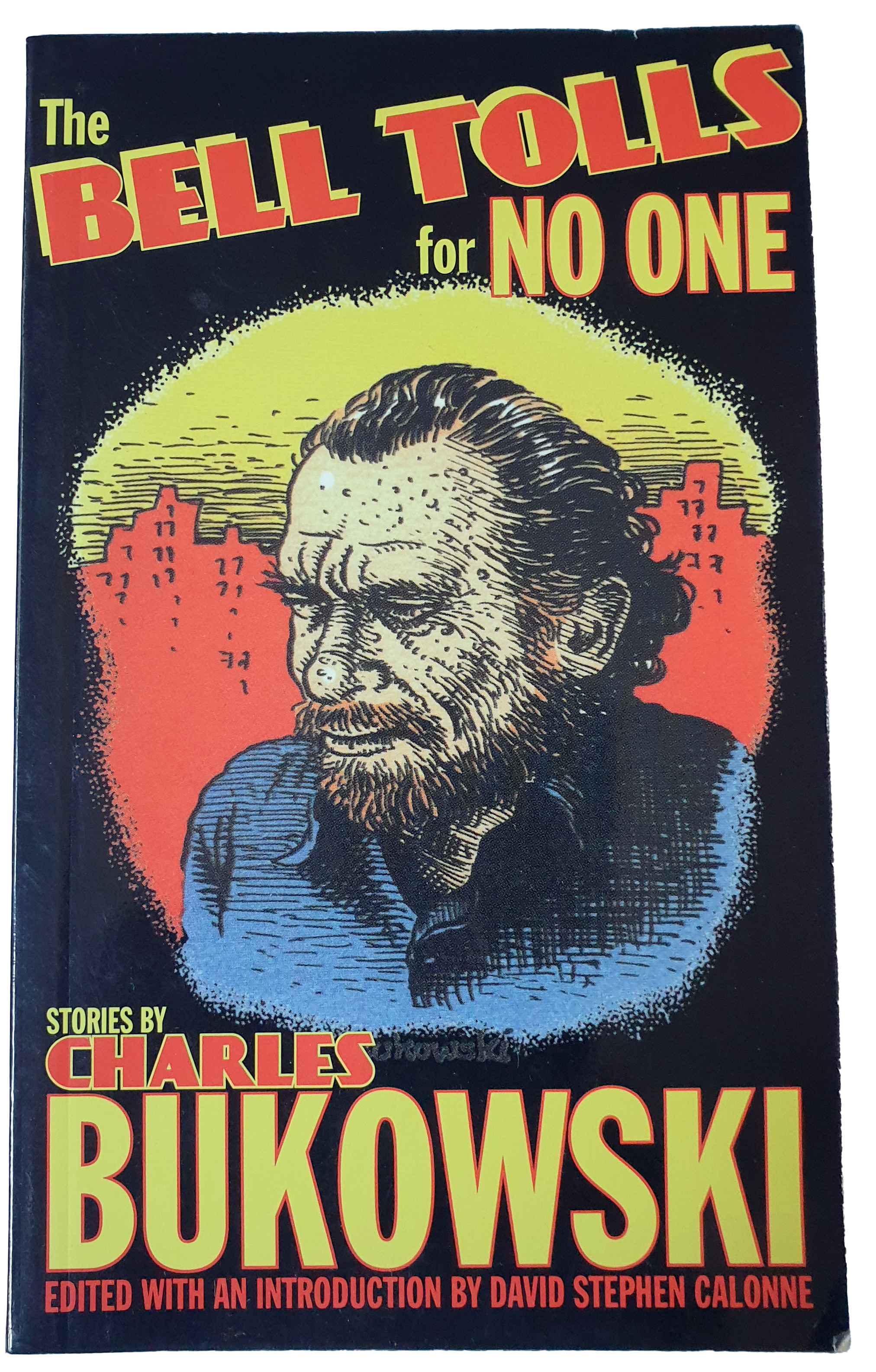

50. The Bell Tolls for No One, CL, July 13, 2015

50. The Bell Tolls for No One, CL, July 13, 2015

A nice companion to the infamous Erections in that most material here is sordid, raunchy, and grimy—definitely not for the squeamish. As Calonne noted, this collection contains “some of Bukowski’s more ‘edgy’ stories. He combined them with drawings and prefigured the contemporary craze for graphic novels.” But, then again, there’s always gold in the city dump: some sort of Bukowskian beauty shines through most of these dreary portrayals. After all, the incorrigible Dirty Old Man was a marshmallow at heart—or so his lovers said. Essential: “A Kind, Understanding Face,” “Break-In.”

.

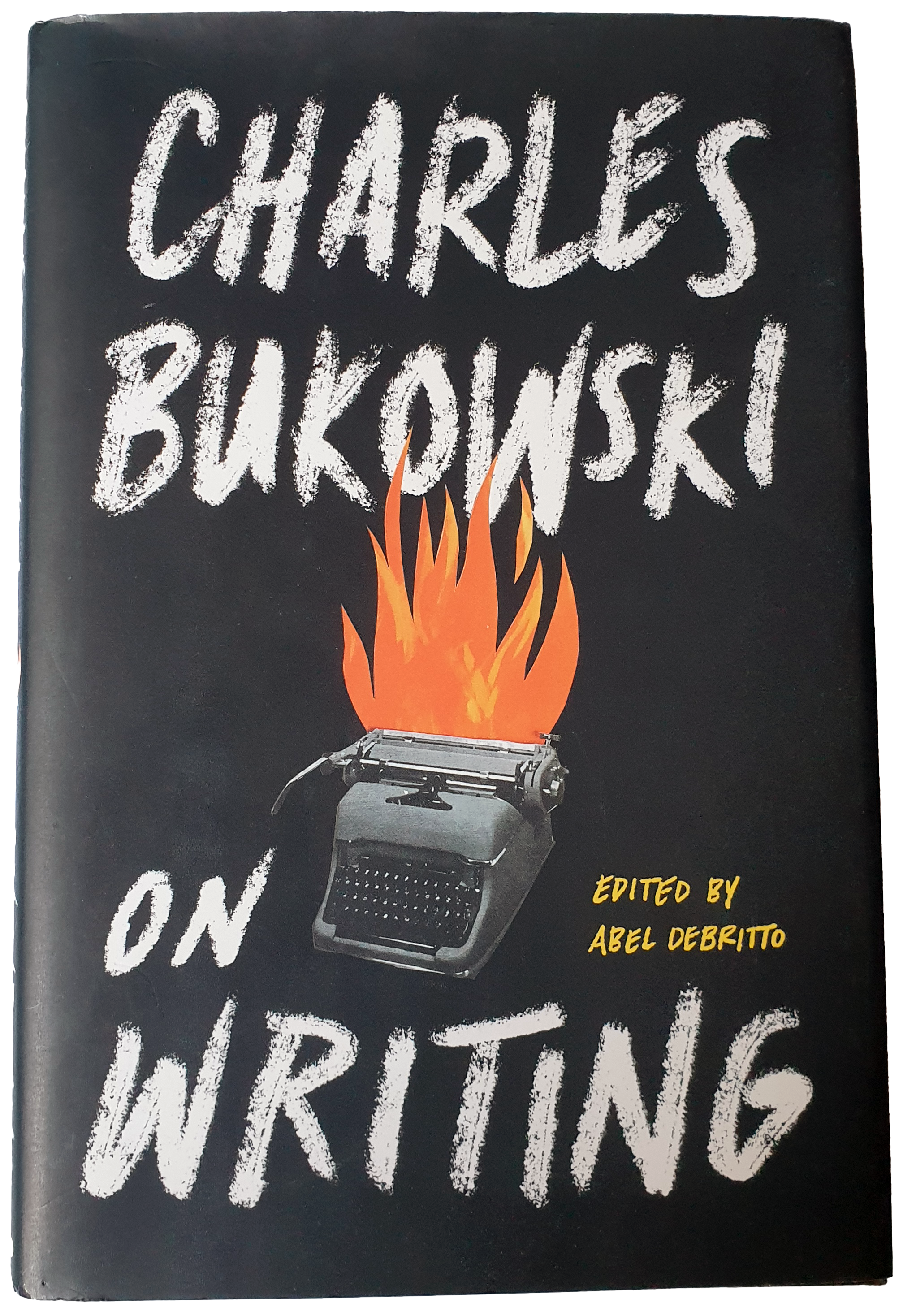

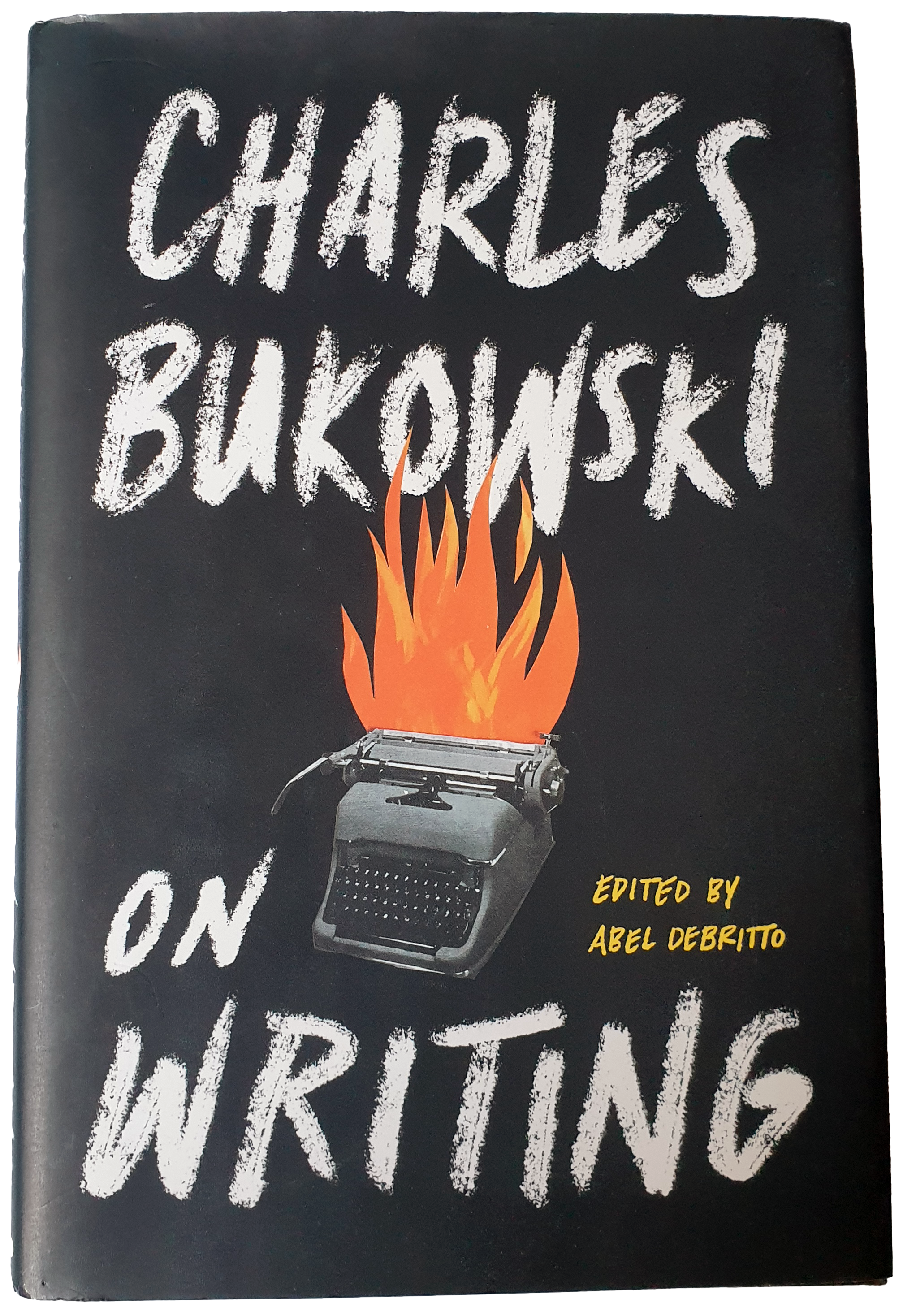

51. On Writing, Ecco, July 14, 2015

51. On Writing, Ecco, July 14, 2015

The first in the ON series, this volume of previously unpublished correspondence features provocative, passionate musings to his friends, publishers, and editors, along with several never-before-seen photographs, facsimile letters, and drawings. The well-versed misanthrope who always downplayed learning found his first true love in writing early on. “There’s music in everything, even defeat,” he says at one point with such conviction that it seems even plausible, like seas parting or walking on water. And, finally, the Buddha of San Pedro confesses in his old age: “There is nothing more magic and beautiful than lines forming across paper. It’s all there is. It’s all there ever was. No reward is greater than the doing.” Essential: the early letters; the ruminations on style and grammar; the ever-present, contagious compulsion to write: “Sometimes I’ve called writing a disease. If so, I’m glad that it caught me.”

.

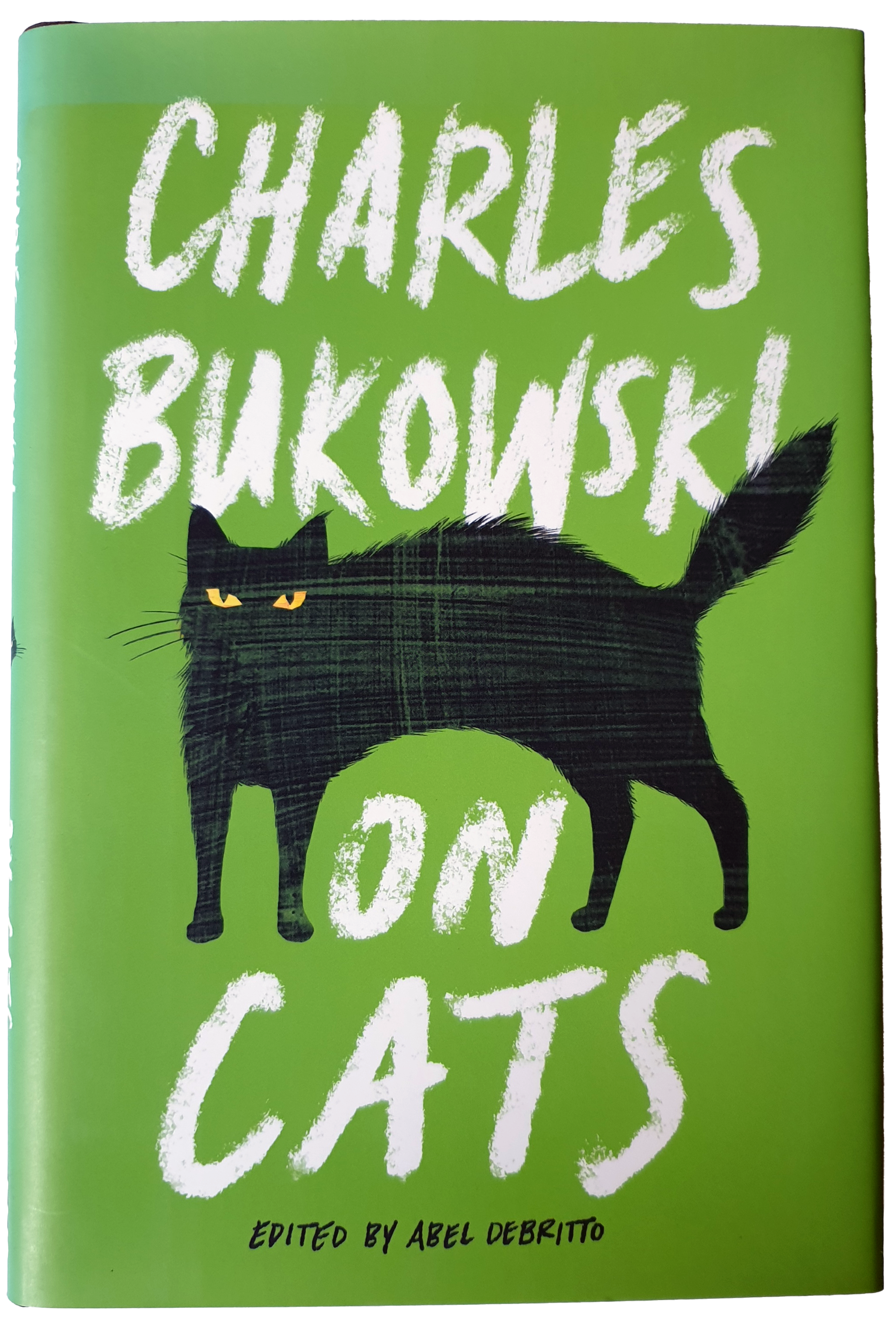

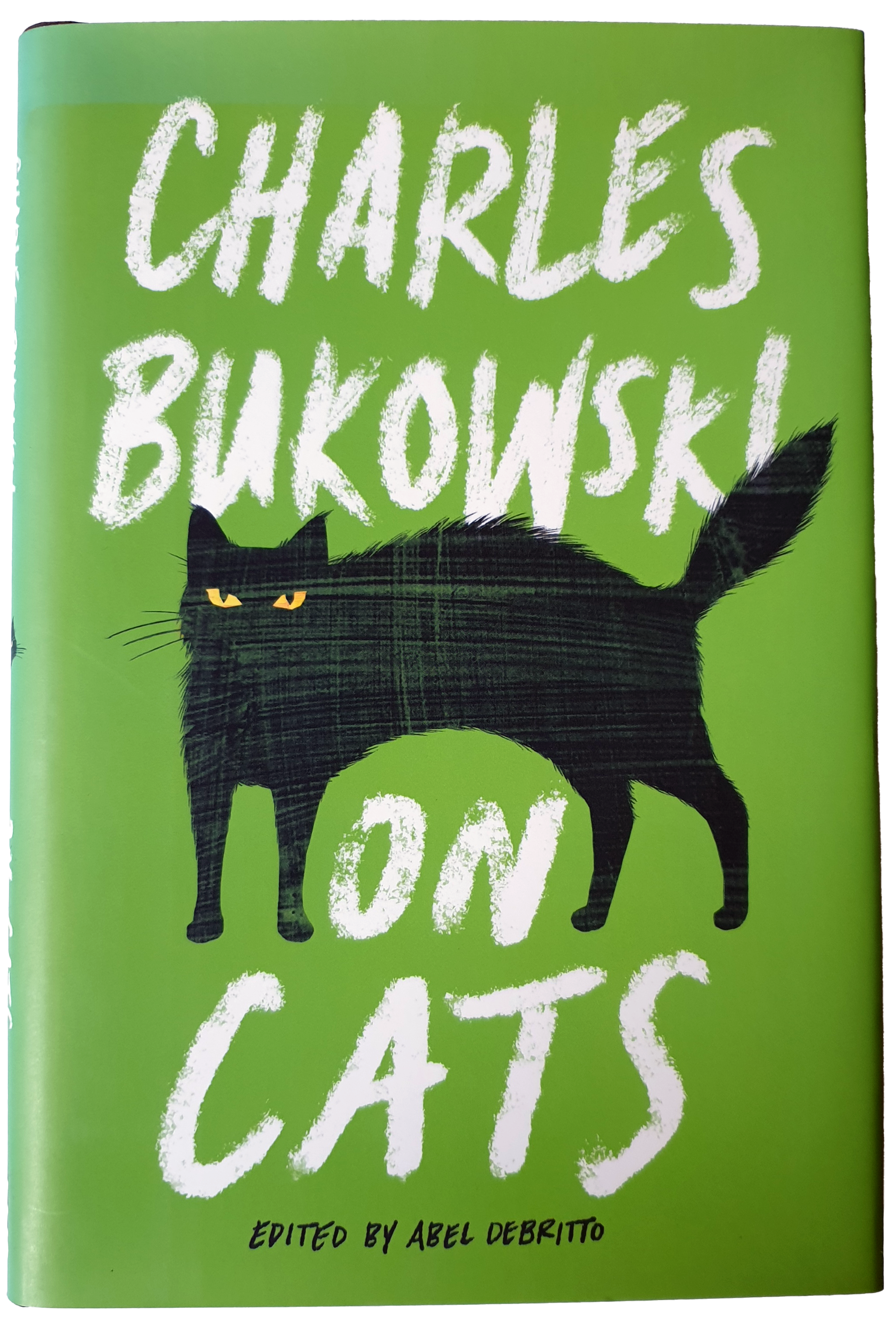

52. On Cats, Ecco, December 2015

52. On Cats, Ecco, December 2015

Without question, a crowd-pleaser, and a popular one at that—it’s the best-seller in the ON series. A mixed bag of drawings, photographs, prose, letter and poem excerpts, featuring previously uncollected and unpublished material. Bukowski shows his affection for cats with unmistakable grittiness, sparing readers of the much-dreaded cloying asides. An early letter sums it up: “The cat is the beautiful devil.” A gentler Bukowski appears in the final pages, calling cats his teachers and writing in stone some wisdom for the ages: “The more cats you have, the longer you’ll live.” Essential: “Conversation on a Telephone,” “Startled Into Life Like Fire,” “One for the Old Boy.”

.

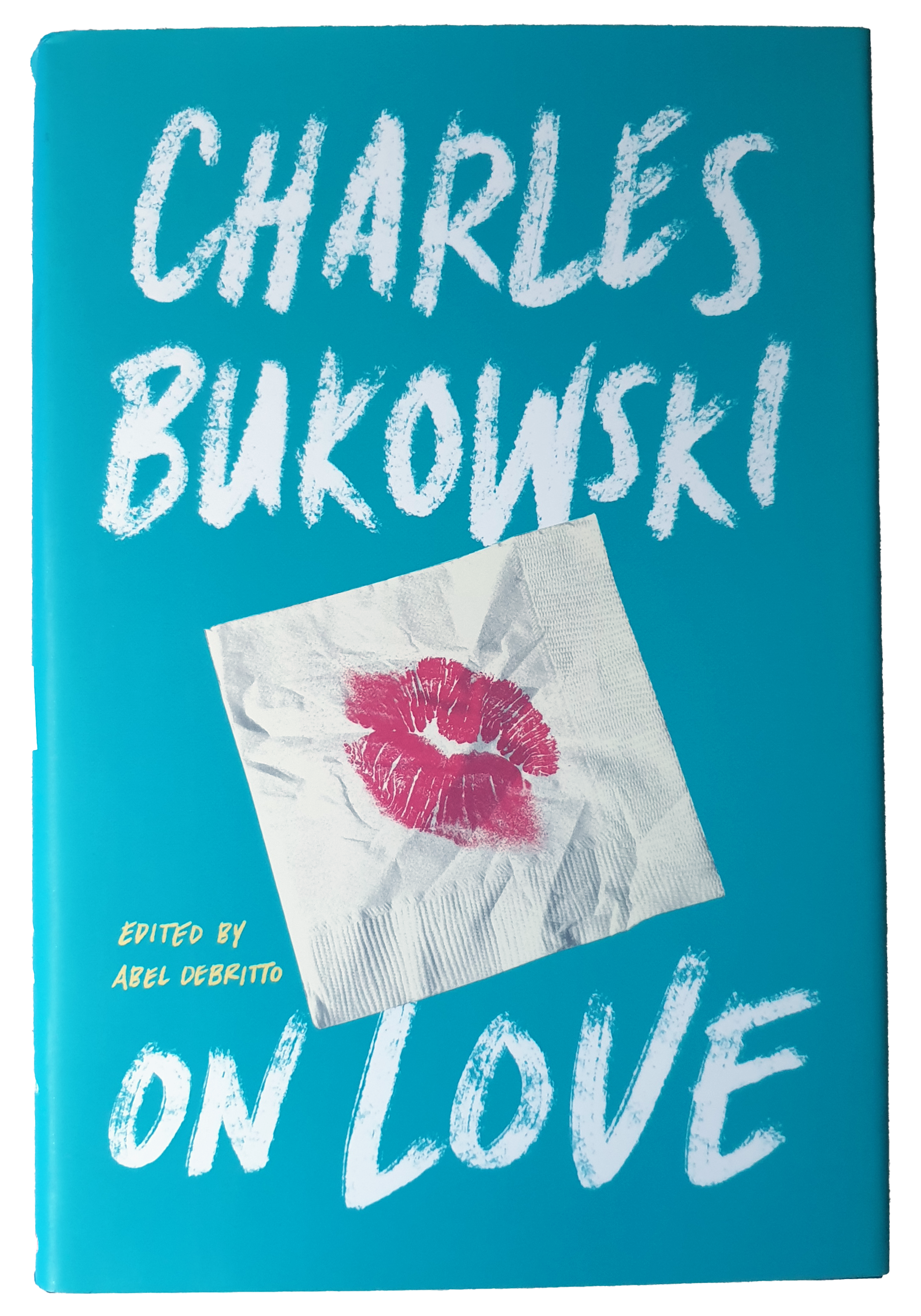

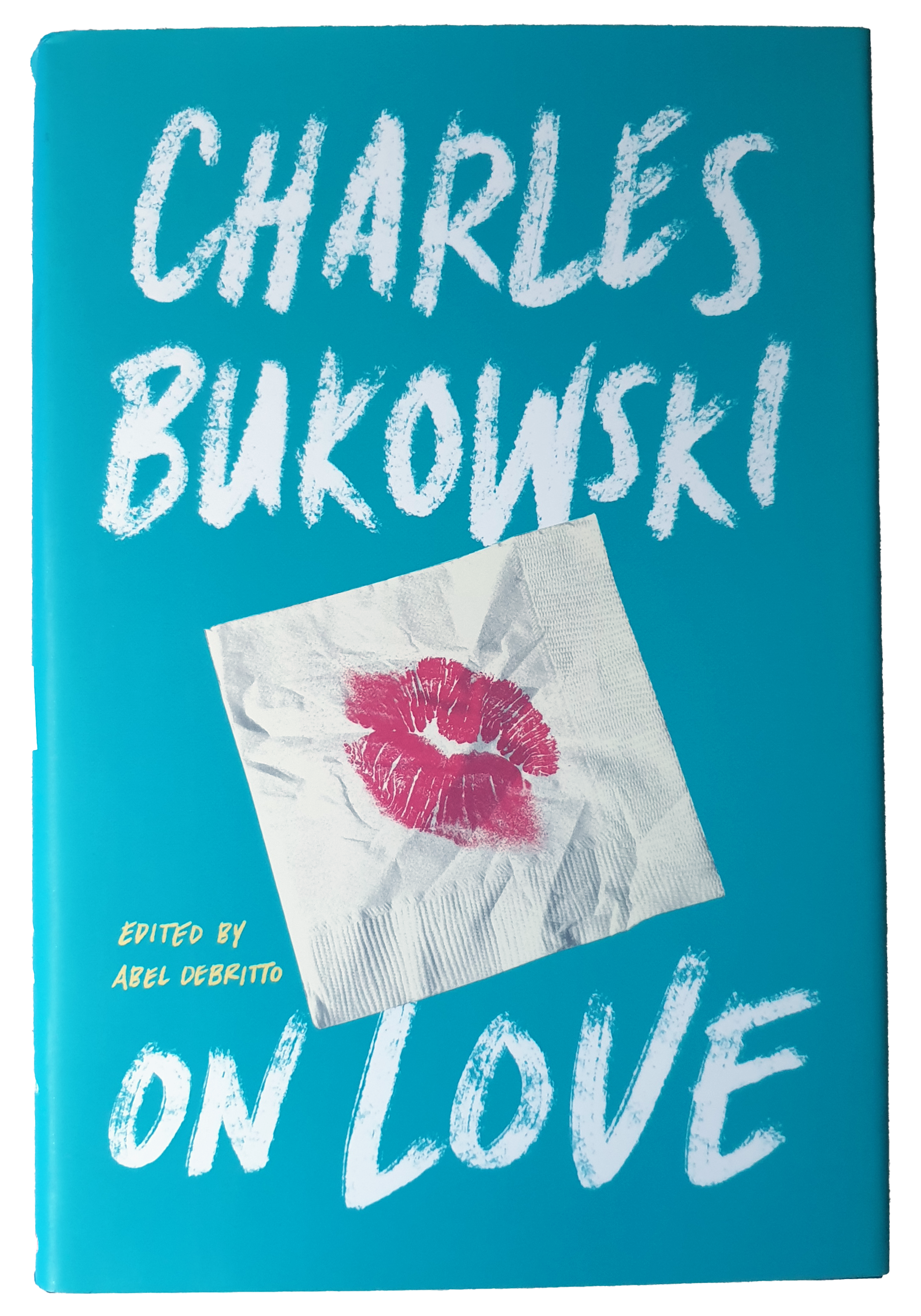

53. On Love, Ecco, February 2016

53. On Love, Ecco, February 2016

On Love happened because On Sex didn’t—Linda objected to the publisher exploiting Bukowski’s dirtiest persona. Another mixed bag of drawings, prose, letter, and poem excerpts along with some new material. As expected, Bukowski’s definition of love is hardly romantic: “Love is the crushed cats / of the universe . . . love is Dostoyevsky at the / roulette wheel . . . love is an old woman / pinching a loaf of bread.” Although Bukowski’s love for women, friends, his daughter, literature, cars, and cats is as raw as it gets, his confession to Linda is anything but schmaltzy: “And the hard / words / I ever feared to / say / can now be / said: / I love / you.” So much for Bukowski the tough, male-chauvinist pig. Essential: “My Real Love in Athens,” “Love Poem to Marina,” “A Love Poem for All the Women I Have Known.”

.

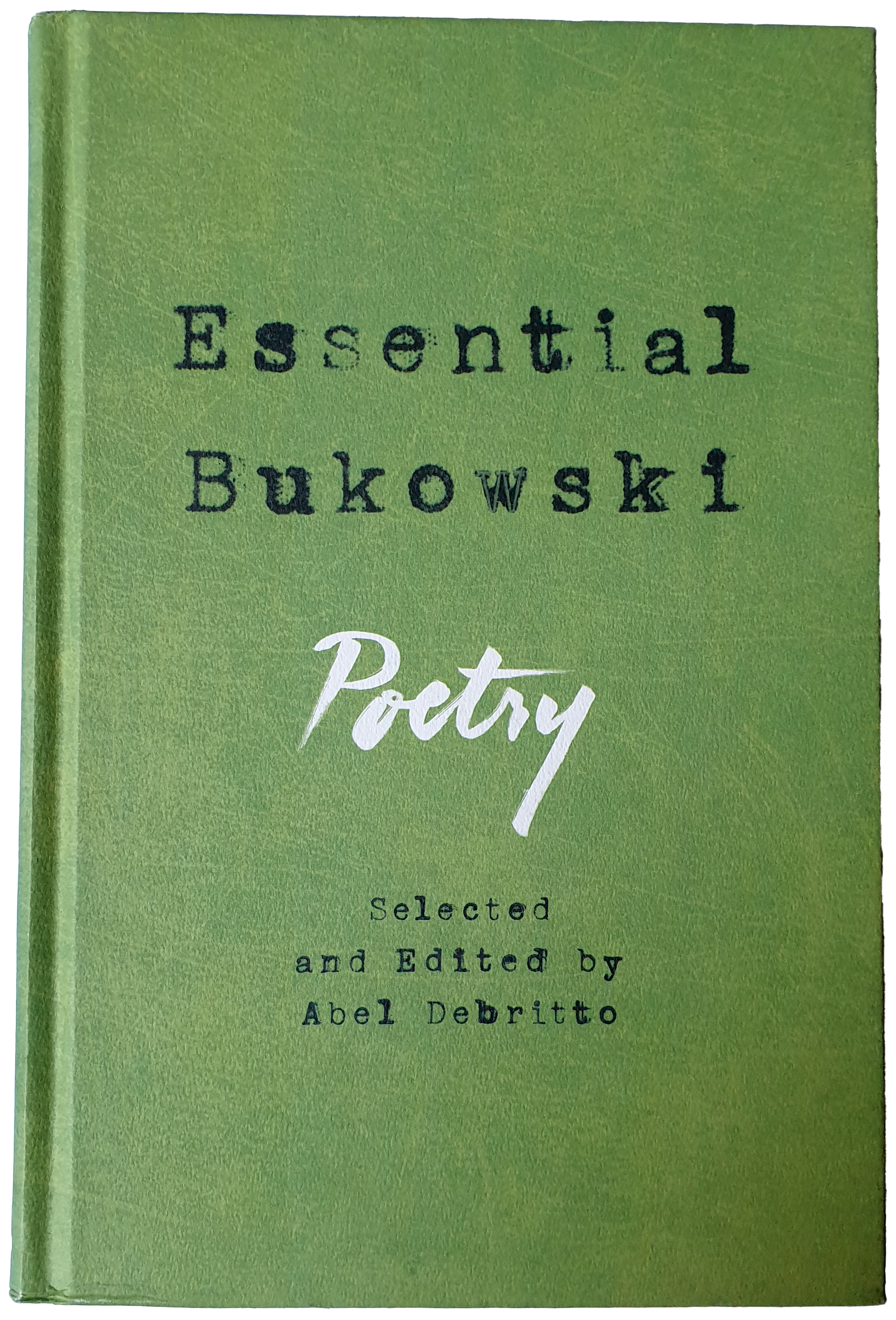

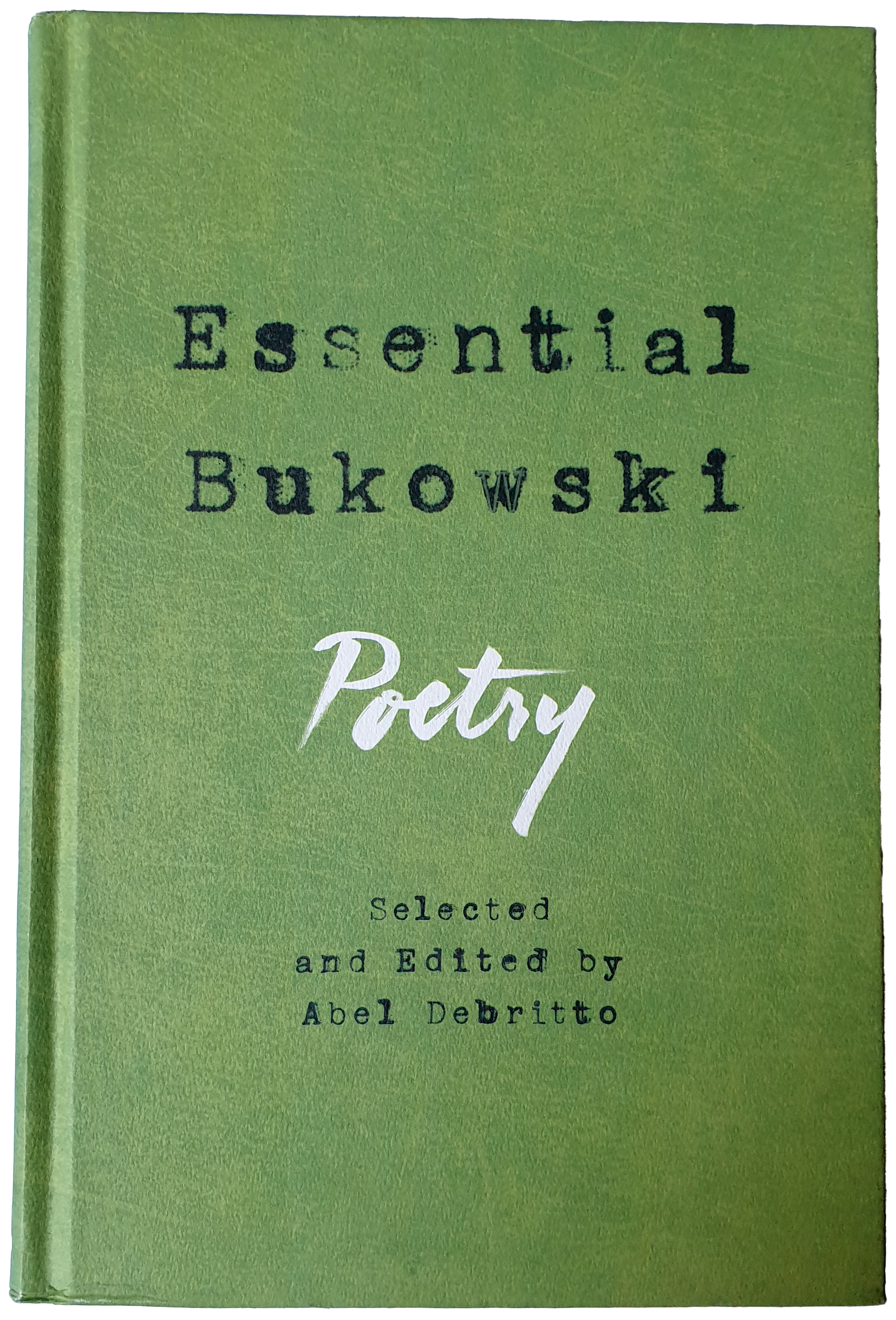

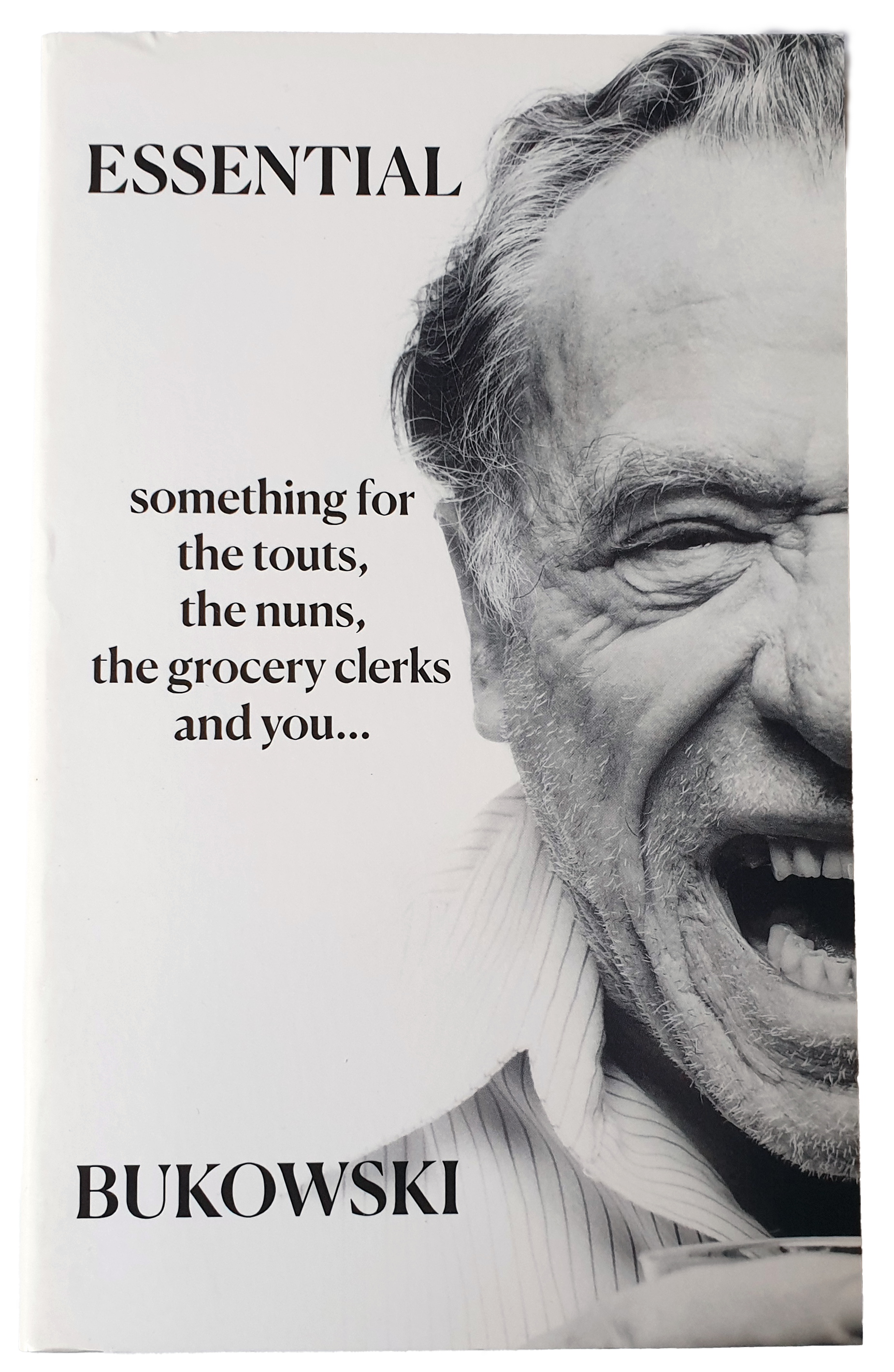

54. Essential Bukowski: Poetry, Ecco, October 2016

54. Essential Bukowski: Poetry, Ecco, October 2016

Boiling down Bukowski’s staggering output to ninety-five poems only is next to impossible—several Essential Bukowski collections are potentially conceivable. A crowd-pleaser of sorts and a steady seller, this collection features the prescriptive classics, poem facsimiles, drawings, and the previously uncollected “swastika star buttoned to my ass” as a tribute to Carl Weissner. Ideal for newcomers and seasoned fans wanting to review some of Bukowski’s most accomplished poems. Reception was unequivocal: “For sheer reading pleasure and consistent quality of content, Essential Bukowski is the best Bukowski book published.”

drawings, and the previously uncollected “swastika star buttoned to my ass” as a tribute to Carl Weissner. Ideal for newcomers and seasoned fans wanting to review some of Bukowski’s most accomplished poems. Reception was unequivocal: “For sheer reading pleasure and consistent quality of content, Essential Bukowski is the best Bukowski book published.”

.

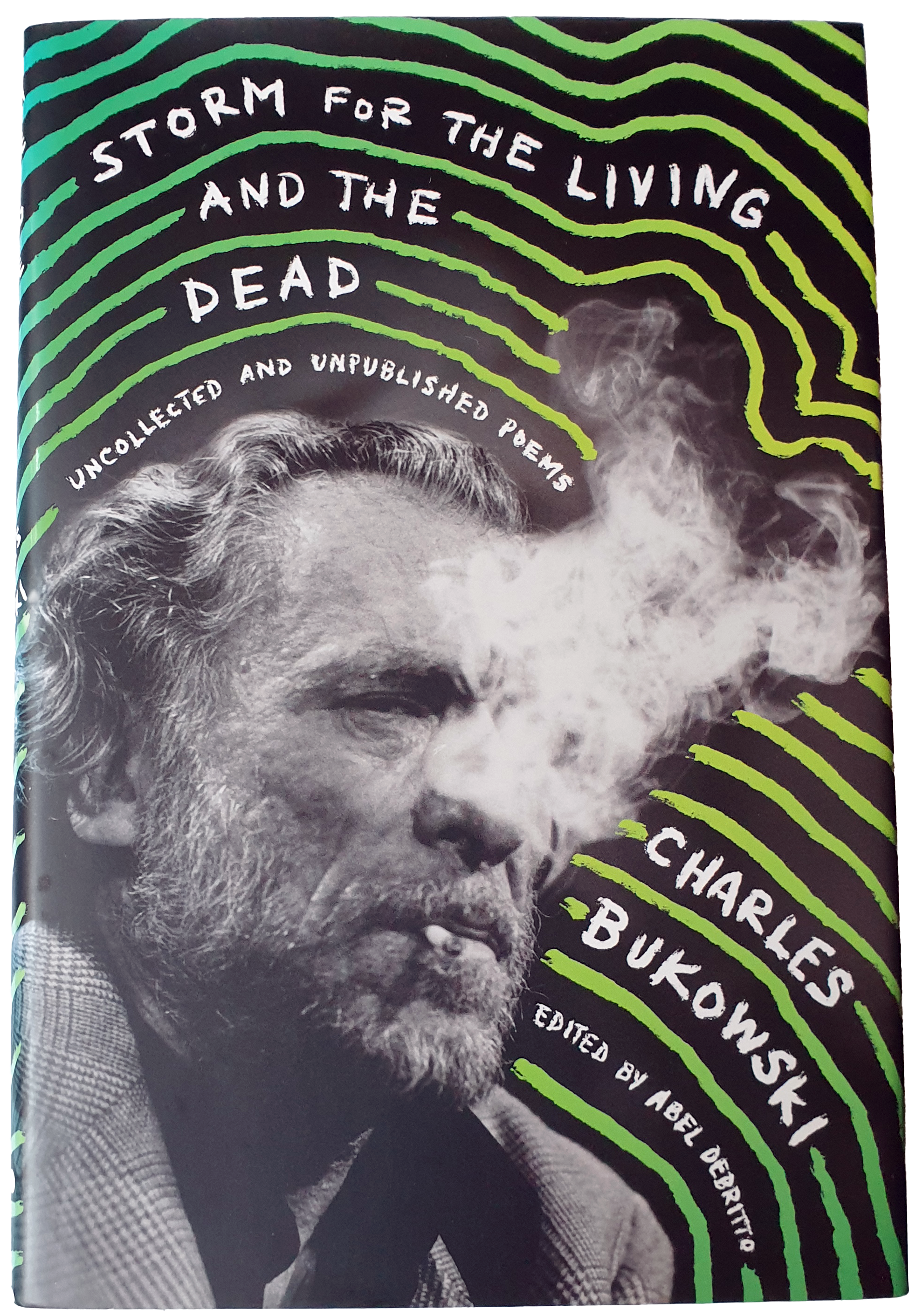

55. Storm for the Living and the Dead, Ecco, 2017

55. Storm for the Living and the Dead, Ecco, 2017

First unpublished poetry collection in twenty-five years to faithfully reproduce all poems as they were originally written, showing Bukowski in the raw, with no shady make-up. Taking no prisoners, Bukowski wrote some of them for their shock value, but rather than being merely offensive and divisive they showcase his dark humor. The inclusion of some experimental poems and a handful of long-lost gems makes for a welcome stylistic variety. Reviews were rightfully disparate: Some called it “drunken drivel” and “the nadir of Bukowski’s posthumous publications,” while at the other end of the spectrum it was seen as “a stunning collection that might be remembered as the single work that best represents the full range—the unmasking, as it were—of Charles Bukowski’s oeuvre.” Essential: “Song for This Swiftly-Sweeping Sorrow,” “I Was Shit,” “Poem for Dante.”

.

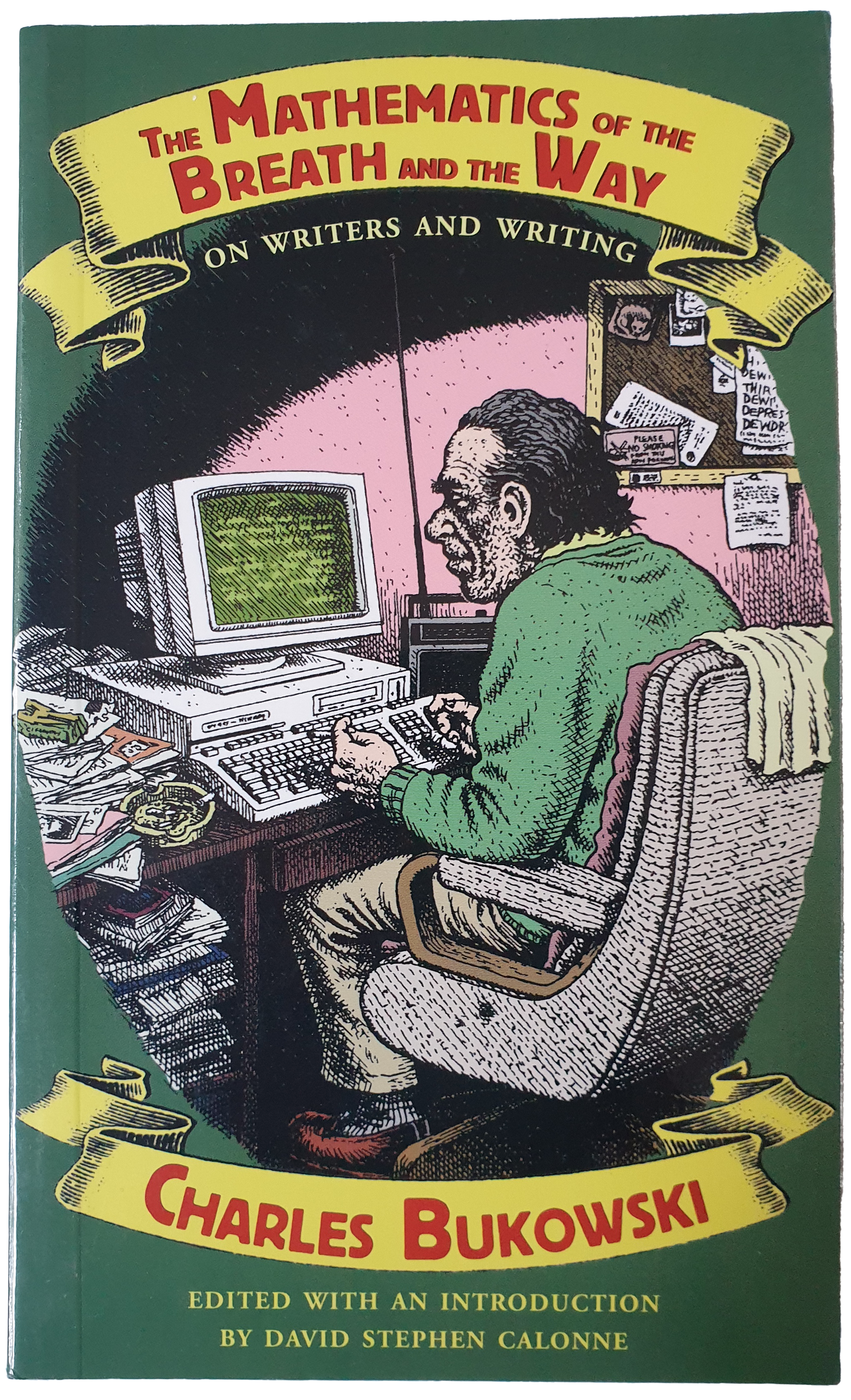

56. The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way, CL, 2018

56. The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way, CL, 2018

The last offering from City Lights stands as an excellent companion to On Writing. As Calonne remarks, it’s “a book of essays and stories devoted to the theme of writing,” including reviews and interviews where Bukowski reflects “on his life as an author who began in complete anonymity and ended as a world-famous literary figure.” Bukowski’s timeless bravado is not lost on the reader: when asked about his advice on writing, he nonchalantly suggests that betting on the racetrack is the way to go. Essential: “Upon the Mathematics of the Breath and the Way,” “Confessions of a Badass Poet.”

.

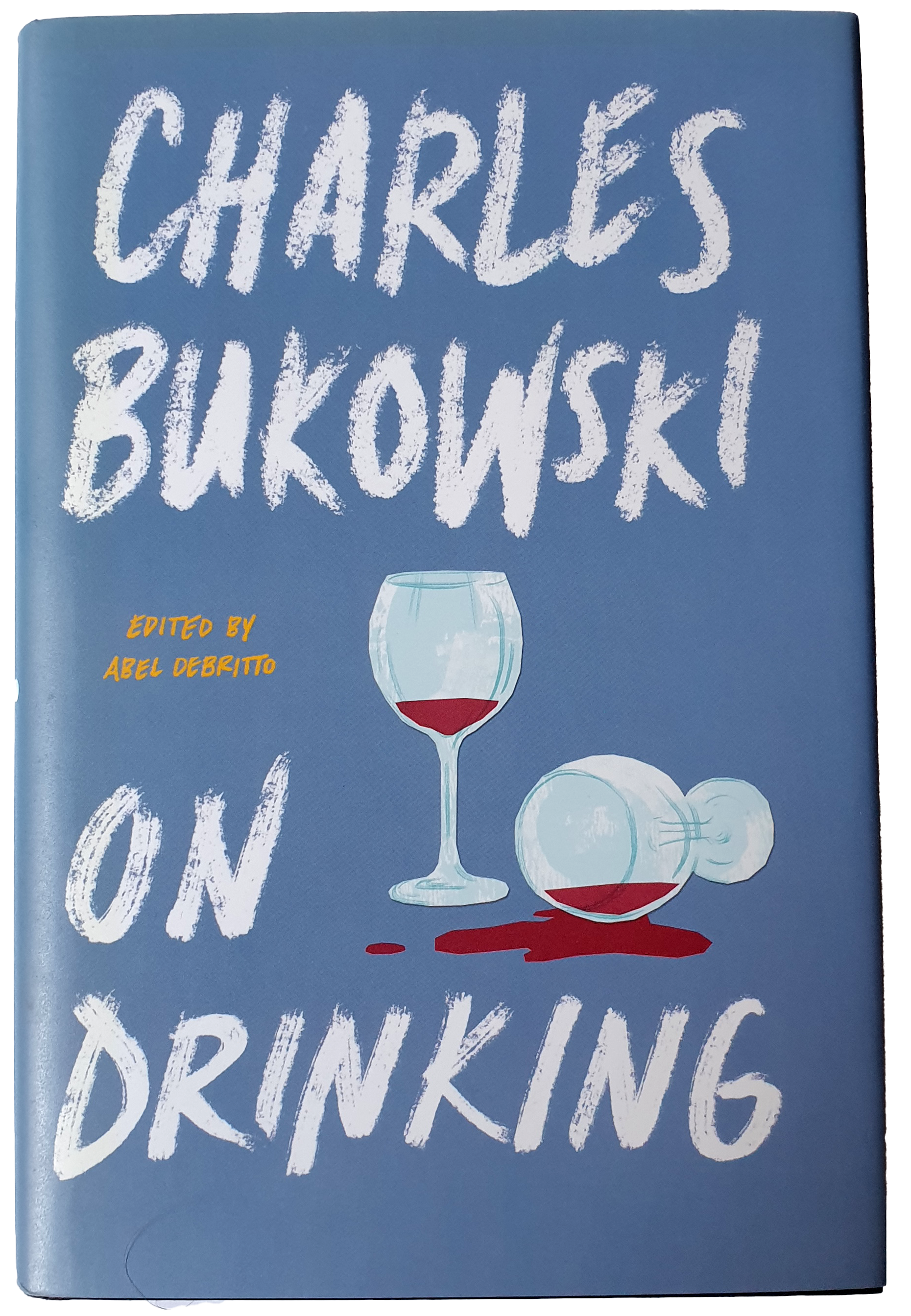

57. On Drinking, Ecco, 2019

57. On Drinking, Ecco, 2019

After discarding On Death and On the Racetrack, On Drinking was the next Ecco collection to hit the shelves. It’s a chronologically arranged volume of drawings, prose, letter and poem excerpts that also features new material. Although Bukowski infamously almost hemorrhaged to death in 1954, he kept on drinking non-stop during the next decades. If anything, alcohol gave him a chance for instant reincarnation: “Drinking is an emotional thing . . . It’s like killing yourself, and then you’re reborn. I guess I’ve lived about ten or fifteen thousand lives now.” Late in his life, he realized that being on the wagon didn’t hamper his creativity: “I think I write as well sober as drunk. Took me a long time to find that out.” Essential: “The Great Zen Wedding,” “Tonight,” “Mozart Wrote His First Opera Before the Age of Fourteen.”

The poet Deborah Meadows has made a career of collaging materials from a wide array of specialized disciplines to create conceptual works with lively, surprisingly personable surfaces. Her work demonstrates what happens when you put together words from disparate vocabularies to achieve a kind of de-specialization suggestive of the fact that postmodern life is, itself, a lesson in hybridity. Her latest book, Bumblebees (Roof Books, $20), is a case in point.

The poet Deborah Meadows has made a career of collaging materials from a wide array of specialized disciplines to create conceptual works with lively, surprisingly personable surfaces. Her work demonstrates what happens when you put together words from disparate vocabularies to achieve a kind of de-specialization suggestive of the fact that postmodern life is, itself, a lesson in hybridity. Her latest book, Bumblebees (Roof Books, $20), is a case in point.the ordinary irrational struggle

Irigaray:

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.

1. It Catches My Heart in Its Hands, Loujon Press, 1963

1. It Catches My Heart in Its Hands, Loujon Press, 1963 2. Crucifix in a Deathhand, Loujon Press, 1965

2. Crucifix in a Deathhand, Loujon Press, 1965 3. At Terror Street and Agony Way, Black Sparrow Press (BSP), 1968

3. At Terror Street and Agony Way, Black Sparrow Press (BSP), 1968

offensive” by critics, these forty-two “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” columns, with hilarious sex-as-tragicomedy undertones, gained Bukowski thousands of readers. The 28,000 copies of the first printing were sold out in months. It was translated into German the next year, getting favorable reviews in major newspapers. Reissued by City Lights in 1973. Essential: the “Frozen Man Stance” section, and the Baldy story.

offensive” by critics, these forty-two “Notes of a Dirty Old Man” columns, with hilarious sex-as-tragicomedy undertones, gained Bukowski thousands of readers. The 28,000 copies of the first printing were sold out in months. It was translated into German the next year, getting favorable reviews in major newspapers. Reissued by City Lights in 1973. Essential: the “Frozen Man Stance” section, and the Baldy story.

7. Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, City Lights (CL), April 1972 [reissued in two volumes in 1983]

7. Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, City Lights (CL), April 1972 [reissued in two volumes in 1983]

15. Shakespeare Never Did This, CL, September 1979 [reissued by BSP in 1995 with 11 poems]

15. Shakespeare Never Did This, CL, September 1979 [reissued by BSP in 1995 with 11 poems]

19. The Bukowski/Purdy Letters, 1964-1974, The Paget Press, November 1983

19. The Bukowski/Purdy Letters, 1964-1974, The Paget Press, November 1983

21. Barfly, The Paget Press, December 1984

21. Barfly, The Paget Press, December 1984

arranged, featuring Bukowski’s most accomplished musings and banter on his favorite topics. As Martin recalled, he “loved telling Hank’s life story in his own words, using excerpts from novels, complete short stories and poems.” A no-holds-barred hagiography that helped Bukowski face leukemia—and death—with his head held up high.

arranged, featuring Bukowski’s most accomplished musings and banter on his favorite topics. As Martin recalled, he “loved telling Hank’s life story in his own words, using excerpts from novels, complete short stories and poems.” A no-holds-barred hagiography that helped Bukowski face leukemia—and death—with his head held up high.

when I saw that billboard, it gave me the courage to go on’.” Readers were empowered by “Roll the Dice,” too: “If you’re going to try, go all the / way. otherwise, don’t even start.” Essential: “A New War,” “Christmas Poem to a Man in Jail,” “To Lean Back into It.”

when I saw that billboard, it gave me the courage to go on’.” Readers were empowered by “Roll the Dice,” too: “If you’re going to try, go all the / way. otherwise, don’t even start.” Essential: “A New War,” “Christmas Poem to a Man in Jail,” “To Lean Back into It.”

drawings, and the previously uncollected “swastika star buttoned to my ass” as a tribute to Carl Weissner. Ideal for newcomers and seasoned fans wanting to review some of Bukowski’s most accomplished poems. Reception was unequivocal: “For sheer reading pleasure and consistent quality of content, Essential Bukowski is the best Bukowski book published.”

drawings, and the previously uncollected “swastika star buttoned to my ass” as a tribute to Carl Weissner. Ideal for newcomers and seasoned fans wanting to review some of Bukowski’s most accomplished poems. Reception was unequivocal: “For sheer reading pleasure and consistent quality of content, Essential Bukowski is the best Bukowski book published.”