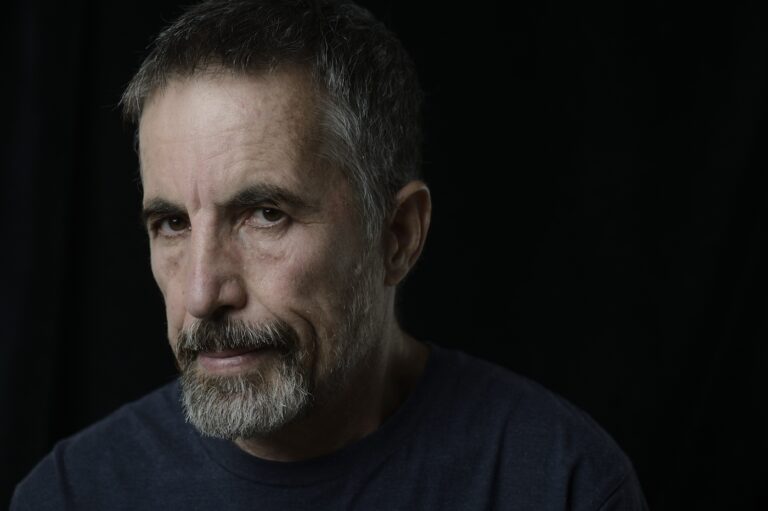

by Marcus Pactor

Youval Shimoni is one of Israel’s greatest living novelists. His ambitious, cinematic fiction weaves together the machinations of his main characters with an impeccable eye for detail and a prodigious knowledge of history. The Salt Line (Crowsnest Books, $29.99), his latest novel to be translated into English, offers a multigenerational and multinational illustration of the varieties of human cruelty and their seeds; the story features Russian revolutionaries and pogroms, Israeli wars and dissolution, revenge caravans crossing the Indian frontier, and much more.

Shimoni won both the Brenner Prize and the Newman Prize for The Salt Line. He is the senior editor at Am Oved Publishing House and a professor at Bar Ilan University.

Marcus Pactor: Many of your characters aim to sever themselves from their pasts, the world, and even history. But no matter how deeply Ilya Poliakov, for example, wanders into the desert, he cannot escape either his past or his influence on future generations. How much of this theme of history’s inescapability did you have in mind when conceiving the novel, and how much crystallized during your writing?

Youval Shimoni: You are correct; it’s a topic that has interested me from a young age. We see someone in a certain situation, and, for the most part, we are not aware of the baggage he carries within. He too, mostly, is unaware—at least as the situation occurs. At this moment I’m replying to you about The Salt Line with its publication in English, and at the back of my mind, as well as my heart, is the French translation of The Flight of the Dove—my first book—and the exaggerated expectations I entertained at the time. At a deeper level in time is the image of myself that occasionally flickers amongst the central characters there, a twenty-two-year-old experiencing first love with a French woman he met in Italy and with whom he lived for a while in an unfurnished apartment, after which he returned to Israel filled with hopeless yearning. There are moments when he seems minute, as if viewed through the opposite side of a pair of binoculars, and there are moments when I’m transferred there, in his place, and that adult of my age becomes blurred and small in the distance.

We all constantly carry layers of our past and buds of our future, and there isn’t a moment when the underside of the layer is not attached to the past while, on the top side, a future moment is already being formed. These layers are not firm like those of an onion or the rings of a tree trunk but dissolve into each other. At times the past weighs heavily like a sack of sand in a hot air balloon, and at times the future is oppressive with the realization that one will have to keep one’s feet firmly on the ground—a grey and heavy future like Parisian wintery skies, another sight from that layer of time.

In Israel one is not only burdened with voluntary or involuntary memory baggage, or factors stemming from genetic makeup and environment, but with the baggage of Jewish history from which there is no respite even in the established state here. This history is not only present in history books, but in the traumas transmitted from generation to generation to the present time. It is apparent in every household, and not only among its dwellers but in the house itself; not only in the present but in the future that awaits us.

The best illustration of the abnormal situation in Israel is our homes, in comparison to other homes in the world—and not from a design point of view. Here, to maintain a sense of security for all house occupants, walls and a roof are not enough. It is mandatory for each apartment in a new building to include a special safety area, a room constructed of reinforced concrete resistant to the bombing that is anticipated in one of the coming wars, whose outbreak is clearly inevitable to all. That’s from the side of a future Middle East reality, while from the other side, that of the past, a mezuza that encases biblical scriptures is affixed to the doorpost of the apartment to provide the occupants with divine protection. Missiles, radar, and anti-missile missiles on one side, biblical scriptures on the other.

MP: Any one of your plots—Poliakov’s involvement with Russian revolutionaries, Amnon’s experience in the Lebanon War, or the caravan’s journey to plant phony relics, to name only a few—might have formed the basis of a lesser writer’s novel. A similar expansive and ever-complicating impulse seemed to be at work in your earlier novel, A Room (Dalkey Archive, 2016). What, beyond predilection, is the root of this impulse?

YS: I find it difficult to perceive as a whole what to me is a part of something far more complex. You mention A Room, my second novel: In it, there is a room with a group of soldiers on an army base, where an inane instructional film is being shot for various army units. I could have dealt solely with the dynamics in that room—characters airing their views about the army, male and female soldiers flirting with each other, bickering and making up and so on—but what interested me were the different worlds that entered the room with them.

In 1990 I returned to Israel from a stay on an island in Thailand straight to the Gulf War. My mind still was still preoccupied with the strip of beach lined with coconut trees, the expanse of ocean, the hut I lived in from whose window I could see a local family, and the danger of coconuts liable of falling on one’s head—coconuts and not Saddam Hussein’s missiles. I was called up for reserve duty in a filming unit, and I could not but imagine what landscapes the others around me carried inside their minds from other times, what hopes and disappointments, loves and frustrations, totally unconnected to the film—it was if they had all been squashed into one room without any opportunity for self-expression.

I attempted something similar, although in a different form, in my first novel The Flight of the Dove; that book has two parallel plots, one appearing on the left-hand page and the other on the right-hand page. The first tells of an American couple touring Paris who arrive at the Notre Dame cathedral, while the second tells of a French woman who decides to end her life by jumping from one of the cathedral’s towers. These stories could have been told in one narrative, but I was interested in the meeting point of the independent plots—only in the very last line of the novel are they conjoined, the one offering a different viewpoint of the other and changing the reader’s viewpoint of both.

MP: The novel’s overall length belies the multitude of its short chapters, many of which are fewer than ten pages long. The beginning of a new chapter often takes us to a different protagonist in a different place and time to either begin or continue a different plot. How did you come upon and manage this massive interwoven arrangement?

YS: True, time and again the reader is led to a different character, time, place, and plot, and for the same reason: The plots overlap, intersect, at times unraveling each other, at times unifying. Is that not, in fact, the way we live with those around us and the plots of their lives, though usually with a narcissistic preference for our own plot that tends to blur all the others? For the most part, there is nothing more important to us than ourselves. Reducing all this complexity into one purposeful succinct plot I find less interesting as a writer, though I can enjoy writing of that nature as a reader.

MP: On the other hand, you narrate the pogrom and sandstorm sequences—two of the finest set pieces I’ve read in some time—without any other plots intruding. What led you to shift your approach for them? Also, the term “set piece” allows me to ask you: How has your background in film influenced your fiction?

YS: These two scenes are close to my heart (as is the Lebanon scene) despite their harsh nature. Describing a caravan of camels in the desert in the middle of a raging sandstorm was a challenge—imagining what my characters might do in its midst, not being able to see in front of them and staying close to each other so as not to disappear in the sand. Describing a Russian pogrom was equally challenging—not to make do with depicting the violent cruelty of the rioters, but also those who hid from them, fearing to come to the aid of the victims, even in the case of a family member. I tried to understand the emotional mechanism in play beyond pure fear.

I read much about those times and places before I felt able to attempt creating a set piece based on their content. Such was the case with the 1905 Russian revolution and the Taklamakan camel caravan. I read dissertations, history books, and the diaries of revolutionaries and explorers to be secure in accurately portraying a village pogrom, an assassination of a minister, and a desert sandstorm.

These are indeed cinematic scenes and certainly hark back to my film studies (which I didn’t complete) and to my love for the media (which remains to this day). Despite the internal baggage of the previously mentioned characters, to me there is nothing more concrete than a scene that unfolds to the eye from one moment to the next. I also derive much pleasure from the direct and immediate manner by which characters are depicted, without their inner baggage and parallel plots. I’ve been told The Salt Line is well suited to a multi-episode series adaptation and would be delighted if someone would take up the challenge—as long as it’s not Netflix.

I myself actually did very little in film: During my first-year studies, I attempted an 8 mm adaptation of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” filming it entirely from the low angle of the insect. Gregor’s mother, father, and sister all spoke to him facing the floor level camera. (At the time it seemed to me a unique idea but later learned others more talented than me had already thought of it.) Later, I made a 16 mm 40-minute film in which I placed a few central characters on a Tel Aviv bus among the passengers, and there too I was mainly interested in what each one brought to the journey rather than the goings on in the bus. It was an unfledged effort that received a tepid reception from its few viewers and deservedly received a single screening.

MP: Tenzin and McKenzie’s scheme to create a religion for revenge is the most memorable display of your characters’ general cynicism about the roots and uses of religion. But I was struck by Poliakov’s brooding over Akavya ben Mahalel’s line, from Pirkei Avot, about a man being a putrid drop. I sensed a more implicit reference to Jewish sacred literature in the recurrence of birds, which reminded me of the proverb, “Like a bird wandering from his nest, so is a man who wanders from his place.” How would you describe the influence of Jewish thought and sacred texts on your work? Do you see yourself as a Jewish writer, an Israeli writer, both, or neither?

YS: My attitude towards religion is not solely cynical; my cynicism is mainly aimed at the unwavering certainty of believers in the fundamental religious narrative and its truths. Cynicism is accompanied by no small fear of those who wish to implement that narrative by the letter and make it a reality. Here in Israel, more and more people wish to build the third temple even at the price of an Armageddon involving all the surrounding Arab states.

In contrast, I have great respect for the writers of the Bible—not only for the quality of the language, but also because of the influence it has exercised over millions of readers, in essence shaping their futures, for better or for worse. The Bible consolidated nomadic tribes or ethnic groups into one body by creating a forefather—Abraham—and by positing an apparently divine right to an already inhabited land. From that story two kingdoms evolved, and after they were destroyed, the story persevered in exile, preserving the Jews as a nation even when they were dispersed over different continents. But it also aroused violent hatred towards them. Faulkner writes about this in “The Bear”: “forever alien: and unblessed: a pariah about the face of the Western earth which twenty centuries later was still taking revenge on him for the fairy tale with which he had conquered it.”

In truth, this fiction shaped history for over two thousand years, and one cannot but be impressed by its power—and shudder at the damage it caused and is liable to cause in the future. Even before prophesying an Armageddon, it grants Israel an apparent license to continue to rule over conquered territories and for settlers to make their home there—to dispossess the Palestinians of their land, to initiate pogroms in their villages, to burn homes, to kill.

The answer to whether I see myself as a Jewish or Israeli writer lies in the fact that many of the central characters of my books are neither Jewish nor Israeli. The Flight of the Dove tells of an American husband and wife and a young Parisian woman; part two of A Room concentrates on three homeless Parisians, and part three, a mythical high priest in the far east. The Salt Line is peopled by a cuckolded English veterinarian, an Italian archeologist eager to make himself world famous, daring and less daring Russian revolutionaries, an Indian caravan-bashi, and many more characters on different continents spread over thousands of kilometers.

I write about what activates my thoughts, imagination, and emotions, for the most part in that order. I first try to understand something about my life at the point in time I have reached, or the path the world has taken up to that point as I see it. This understanding involves creating an alternative plot in the imagination, intensified and more concentrated than the one taking place in reality, and incorporating the emotion the entire process arouses in me.

True, my works have more than a touch of the Jewish and Israeli milieu into which I was born and live, but not everything is delimited by it. The world is somewhat larger than the state of Israel and humanity somewhat greater than the Jewish people.

MP: Windows recur in your work at least as often as birds. Through them, your characters witness events ranging from pitiful to horrific, and those events drive them to various heartbreaks and degradations. How are you able to use and reuse this seemingly mundane image so that, over the course of the novel, its power accumulates rather than declines?

YS: I wasn’t aware of that—Poliakov watching the pogrom with his mother from the attic comes to mind—but I wouldn’t be surprised if you found other windows. I am interested in the aspect of being an observer from afar or from the side and that of intervening in an event in order to stop it or change the order of things. There is a marvellous piece by Kafka, “The Men Running Past”; in it, a man runs towards us on a nighttime street while another man chases him, and only we see this—should we act or find all sorts of excuses to stand still until they disappear from our eyes? There’s never any shortage of excuses.

A totally different window comes to mind. I spoke earlier about the island I had been on in Thailand. I chose a beach during the period when tourists don’t visit, and the huts erected for them go unused. There was no electricity or water, the doors hung on one hinge, and large lizards had moved in. From my window I could see the Thai family that was supposed to look after the tourists and had been left idle. In the afternoon, the mother would delouse her daughters’ hair with her fingers and crack each louse between her nails. In the evening, under the open-sided shelter intended for the tourists who had not come, an oil lamp was placed in a bowl of water on a table. It was completely dark all around and the masses of insects attracted by the light were scorched by the lamp’s glass covering and fell into the bowl of water. The man would make the water move with all the insect bodies and gaze at it like a sound and light show. But everything that seemed exotic in the beginning appeared less so a week later: The concern and love of the delousing act did not seem any different to every western mother brushing out her daughters’ hair, and the hypnotic state of her husband induced by the sound and light show seemed no different to any television screen gazer. Small things soon became apparent: when the mother was angry at her daughters and when they came to appease her, each in her own way; when the wife was irritated by the husband who for most of the day did nothing, when he was so kind as to respond to her requests, and when delight was kindled between them.

The boundaries of my window became more and more unclear, and there were moments when I felt as if I was a guest at their table. Had I remained there longer, perhaps I would have crossed the distance between the window and the open-sided shelter; that is to say, had I also been a different person.

MP: Nachman’s research leads him to believe that “the perception of time … decided [religious believers’] attitude toward death and marked their death and marked the difference between religions.” Do you also share this idea of a connection between religion, time, and death?

YS: Nachman, the father of the main protagonist, dealt with a subject that I too dealt with in the past and on which I published a lengthy treatise called “To Dust.” My argument, which focused mainly on the Bible, was that the solution of every religion in regard to man’s awareness of his mortality is based on its perspective of time as laid out in its fundamental narrative.

The Christian narrative focuses on the birth, life and death of Jesus, and the explanation it offers for his crucifixion—dying for the sake of humanity—grants the Christian believer life after death. The Jewish narrative, in contrast, describes in detail the continuum of generations that creates a nation, and the eternity promised in the Bible is not that of the individual but of the entire nation for all its generations.

Abraham had been put in the position to make the terrible choice between his single son and the seed of generations, and only when he chooses the second and is prepared to sacrifice his son is a ram sent to replace Isaac.

In Hinduism the perspective of time is far, far greater: Its cycles of creation and destruction last 12,000 years and since each year equals 360 regular years, each cycle in fact comprises 4,320,000 years. And if that isn’t enough, 1,000 cycles form one kalpa – 4,320,000,000 years—which is just one day in the life of Brahma. In comparison to all that, a day of the Hebrew god is less than a blink of an eye: “For a thousand years in Thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past” (Psalm 90). In the immense Hindu perspective of time, with its endless reincarnations, man’s greatest aspiration is not to live for eternity, but to stop being reborn, to escape the cycles of birth and death.

MP: I think readers of both The Salt Line and A Room will experience time not as a linear but a simultaneous experience. That is, your characters seem to live their pasts, presents, and sometimes their futures over and over again, and all at once. How do you create this sense of simultaneity?

YS: Literary giants have preceded me in this. Threads from various times and levels of awareness merge in Molly Bloom’s stream of consciousness; Beckett’s Krapp listens to tapes from previous decades of his life as Beckett predicts his future. Faulkner not only made the famous statement, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” but in a 1957 interview described the present stretching forward to 2057 and back to 28 B.C. His protagonists in The Sound and the Fury are subject to flashes from the past flickering in the present, searing and splitting it and sealing their futures. In The Salt Line the consciousness of the characters is mediated by the narrator, and the flashes are prolonged, giving them a scope that is at times much larger than the daylight of their lives. The sense of simultaneity you mention is in fact a sense that each one of us is meant to feel, but fortunately don’t, because doing so for a lengthy time would make living impossible.

While answering you, I recall the experience of first reading Faulkner years ago and the young man I was at the time, still dreaming of making films, as well as the house I lived in outside of Tel Aviv with its yard containing two tortoises, a male and a female, and the loquat tree visible from the window—here right now an ornamental tree with yellow flowers can be seen—at the very same time I’m wondering how this interview will be received and if it will help The Salt Line (I certainly hope so), and on my right is a cup of tea becoming cold as I formulate the answer, a Denby cup whose rim is slightly broken, and I still recall how angry my wife Ayelet was, because I hadn’t taken enough care with the gift she had given me, and twenty years since I have kept it. All these times exist in this moment, but for me to be able to answer you—and to simply continue living—I have to put them aside.

MP: Is there perhaps some hope despite history’s inescapability?

YS: When discussing hope, I would like to differentiate between people living in Israel and those living in other places in the western world. I harbor a deep fear that Jewish history and its consequences are liable to once again create a trap from which there is no escape. The Biblical fiction, without which the establishment of the state of Israel in its present location would not have occurred, had already caused two exiles and two returns in the past: one before the common era and one in the last century. The two ancient kingdoms that arose here did not last long, but the Biblical narrative that persevered for thousands of years fed a never-ending yearning in exile.

We are now in a situation where Israel is threatened from without and from within; by the millions of Arabs in the surrounding countries and by the split that is now dividing Israeli society. The split is allegedly over matters of law and government, but beneath it, and together with the tension between ethnic groups that Netanyahu rouses in order to extricate himself from the court cases pending against him, lies the deep disagreement between those who hold the Bible as divine truth and those who fear the tyranny of its fiction with all its laws and values, between those whose futures are tied to the past by an apparent divine promise of a mythical latter days vision preceded by an Armageddon and those who wish to forge their own future by themselves; between those who believe they are the chosen people of a god waiting for them to rebuild his temple in the place where mosques now stand, and between those who reject this false belief and its claim of superiority and choose to focus on the holiness of human life—Jewish and Arab.

In Paris the French are currently demonstrating over pension reforms, while here masses of people are demonstrating over the future of a state not yet a century old, alongside which a Palestinian state should have been established a long time ago for the millions who live under Israeli occupation.

One should not give up on the possibility of hope, even here in Israel. In the discouraging march of history (not only in Israel—world disasters such as climate change and others loom for all), one should aspire and work towards making each grain of time as positive as possible, positive for us and those who live among us—not perfect, but as positive as is in our power. Our power is not great, and sometimes it’s easier to become despondent or lazy and find all sorts of excuses, but under no circumstances should the attempt be abandoned.

There is always a certain consolation to be found in literature and other art forms, because even when the situation is gloomy and they too are gloomy, they allow their creators to work with the stuff of reality in the manner they wish, putting their own stamp on events and recreating a world on the page. They make it possible for readers to feel the threat has been temporarily contained between the covers, to detach from it and return home and gaze at the tree in the window, the one with the yellow flowers. At that very moment, a cloud is above it and in a short while will continue on its way.