Vítězslav Nezval

Translated by Jed Slast

Twisted Spoon Press ($19)

For those who enjoy strolling around a city they know well or don’t, which they live in or visit; who have no particular destination in mind; who wander at different times, drawn by places and people they encounter and which, for intimate reasons, captivate them, will find an ally in A Prague Flâneur. Its author, Vítězslav Nezval, founded the Czech Surrealist Group and was one of the leading poets and writers of the avant garde. A Prague Flâneur is Nezval’s paean to the city, his city, then on the brink of disaster: The Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia was complete by March 1939, soon after the publication of the book.

The flâneur, of course, comes to us from mid-19th century France. In The Painter of Modern Life, Baudelaire depicts the figure as a stroller who observes in poignant detail what he encounters in and around a city but who keeps his distance, preferring to represent the experience in solitude, visually or with words. Some eight decades later, Nezval reveals the legacy of the term anew. Inspired by Prague’s polyglot architecture, mechanized systems, distractions, crowds, and those rare spaces (streets, parks, playgrounds) that can transform the normal urban chaos we expect, enjoy, or endure, Nezval orchestrates the city’s analog—the book.

Nezval’s writing style mirrors the kind of critical-poetic journalism with which surrealists captured the currents of cities—particularly their marvelous, disorienting, delirious, or dreamlike aspects. A Prague Flâneur is replete with historical descriptions of this or that street, building, restaurant, or café, and how they played in Nezval’s life— from his days as a poor, hungry university student to his rise as a literary figure—as well as brief sketches of writers and artists important to him. As he describes it, Prague takes on a multiform, resonant charge, socially proscribed but personally invented.

After Nezval, others continued to revive the legacy of the flâneur as they conceived it. A decade on after World War II, the Situationists’ dérive (their drift through the city) provoked theoretical remarks on a new context: psychogeography, a term they coined and which, as things go, now appears as a sub-discipline of geography. Heightening the stakes for Nezval, though, are two pivotal events that bring an often-feverish poise to his writing: the immanence of World War II and the fate of the Surrealist Group.

The former stems from the September 30, 1938 signing of the Munich Agreement, by which England and France ceded to Nazi Germany the Sudetenland, then part of Czechoslovakia—a Hail Mary to delay the onset of war that Nezval knew would fail; the only question was when. Anxiety percolates through the book, sharpening its tempered edge. The planes that fly above Prague presage the battle to come. The country arms only to fall months later, betrayed by its allies.

The latter involves Nezval’s split with the Surrealist Group, the repercussions of which followed him and now cannot help but appear as subtext to the book’s exuberant, elegiac tone. The cause of the split was partly political: Nezval supported the USSR, despite the terror Stalin unleashed on his opponents. The majority in the group criticized Stalin’s hunger for victims, which included leading Russian poets and artists, Communist revolutionaries, and uncounted allies or bystanders. Most were put on trial, given sentences, exiled to the Gulag, or executed. There was no possibility of rapprochement.

Nezval’s recognition that only the USSR could mount a force equal to that of Nazi Germany and wage war against it to victory was true enough in retrospect. The other members of the group—whom, oddly, Nezval never names—re-organized and continued on. Perhaps for emotional balance, Nezval recounts his friendship with André Breton and Paul Éluard: the mutual esteem they held for each other, several experiences they shared in Prague, and something of their rich collaborations. A somewhat specious critique of psychic automatism follows, which allows Nezval to clarify how he would write from then on (faced with the immanence of war, cultivating the absence of intention was not something he prized). Be that as it may, when Nezval leaves his apartment, he enters a realm that he creates: the city as his avatar, with chance their conductor.

A Prague Flâneur lives up to its title in a fraught historical moment through which Nezval sought a way to live without sidelining in his writing the inspiration Prague gave him and that he now gives the reader: walking through it, loving and fighting in it, playing out his days and nights with a keen sense of what makes it all unique, even funny (a satirical escapade with an escaped crab its capstone).

This translation, finely done by Jed Slast, is of the rare, unexpurgated first edition with photographs by Nezval, which hit the streets in the fall of 1938, coincident with the signing of the Munich Agreement. Given the consequences of that agreement and the Nazi conquest soon to come, Nezval had the book pulled from its bookstores so that he could delete passages that might compromise him with Nazi authorities, including his celebration of Stalin and his cutting portrait of Hitler as a young agitator of the lumpenproletariat in seedy Berlin beerhalls. An appendix carries that content and the edits Nezval made.

Characteristically, Nezval ends the book with a brief paragraph that recalls the narrative’s through line. It has a solitary atemporal quality—not yet mythic, but almost so. Place it as the first paragraph in the book and it works just as well. Is it an ending or a beginning? For Nezval, it could be both:

Oh Prague, I turn you in my fingers like an amethyst. But no. I just walk, and I see in the magical mirror of dusty crystal that is Prague the animated expression of someone who is fated to find himself and to wander, to find himself through wandering.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2024-2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025

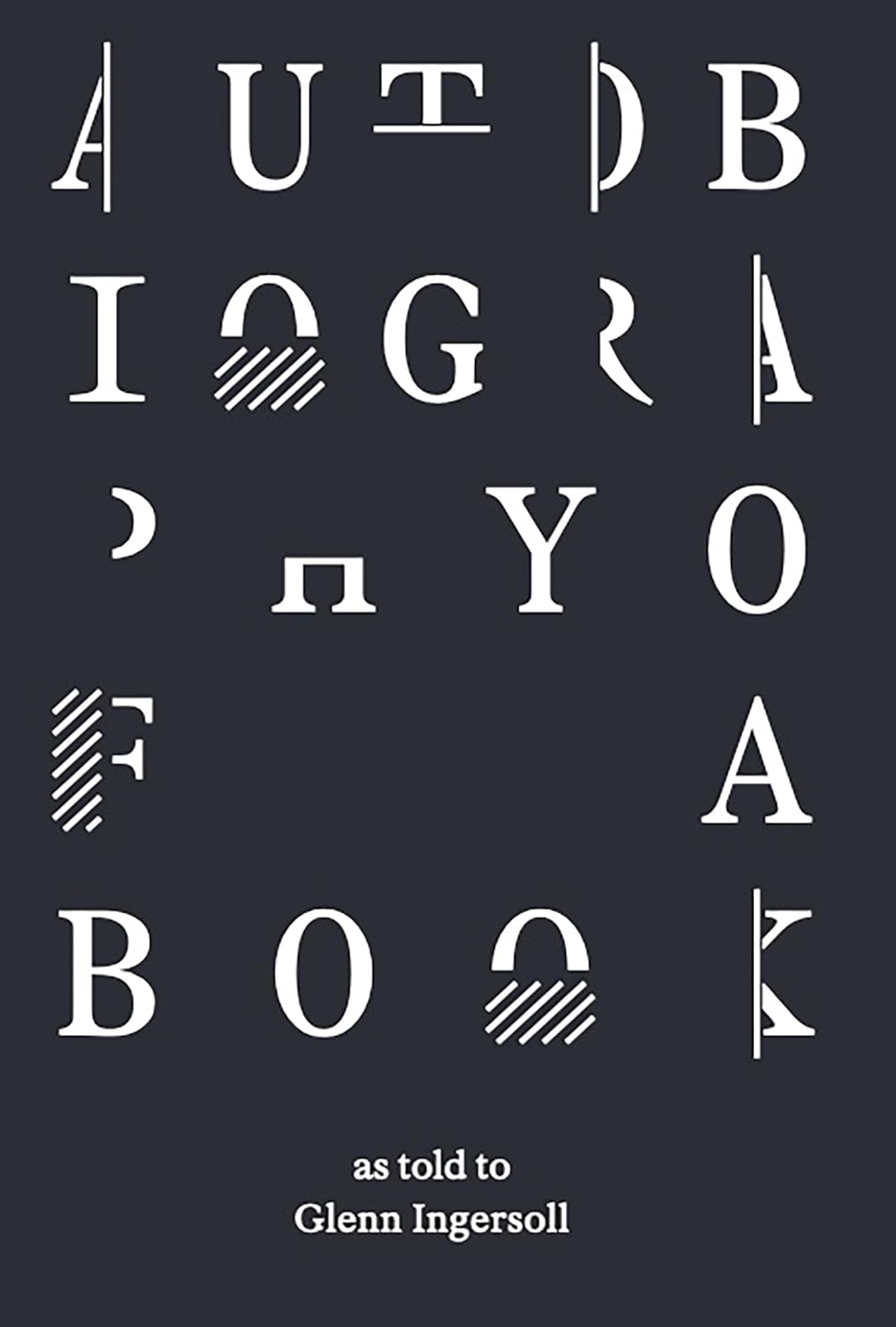

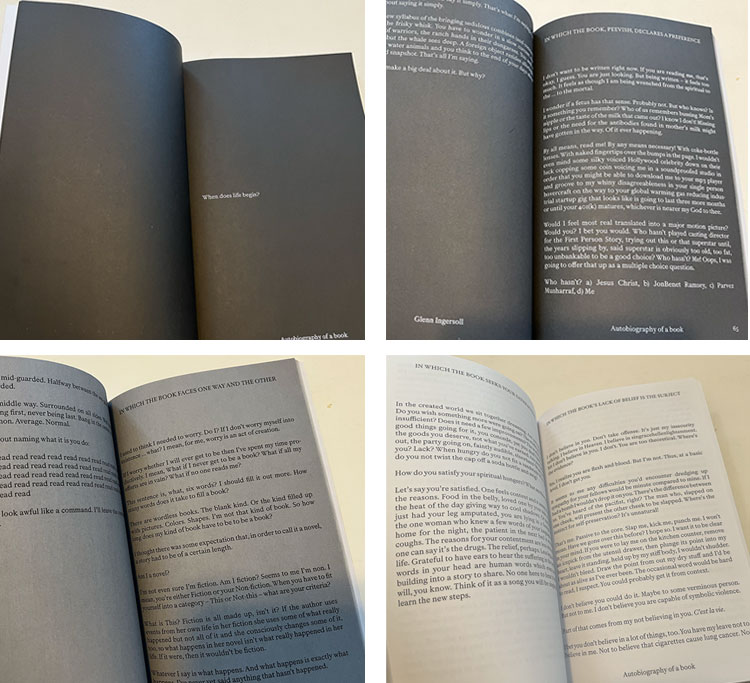

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

We march and we march some more

We march and we march some more