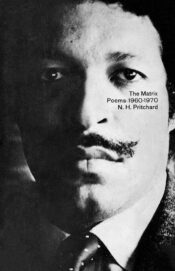

The Matrix

N. H. Pritchard

Primary Information ($20)

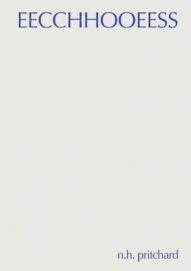

Eecchhooeess

N. H. Pritchard

DABA ($24)

N. H. Pritchard (1939-1996) was a New York-based artist and writer whose The Matrix Poems 1960-1970, originally published by Doubleday, has the significant distinction of remaining the most innovative one-author collection of poetry ever released by a commercial house in the U.S. It was groundbreaking at the time not only for its typographical and verbal departures, but for its author’s race, as fifty years ago, in the wake of Civil Rights protests in 1968, our commercial publishers became more open to Black authors than they had been before. It is only appropriate that his innovation be honored now in our current time with new reprints of his two major works.

The Matrix’s cover had a knockout black and white photograph of its author with half of his face in shadows, wearing a collared shirt with a tie and jacket. Pritchard looked elegant, much as Ralph Ellison was elegant—but whereas Ellison emerged from a fatherless family, Pritchard’s father was a physician who immigrated to New York City from “the Antilles,” as his son so elegantly put it. Whereas Ellison didn’t finish Tuskegee, Pritchard went to prep schools before taking his B.A. with honors from NYU and continuing with graduate school in art history.

When I first met Pritchard in the early 1970s, soon after The Matrix was published, he greeted me in his darkened studio apartment on Park Avenue. Though only a year older than me, he seemed not just more sophisticated, but unique in all the ways that a creative person can be. Pritchard’s personal letters resembled the illuminated manuscripts of William Blake; to my copies of his books he added not just a personal inscription but a handmade enhancement of colors and lines that I treasure.

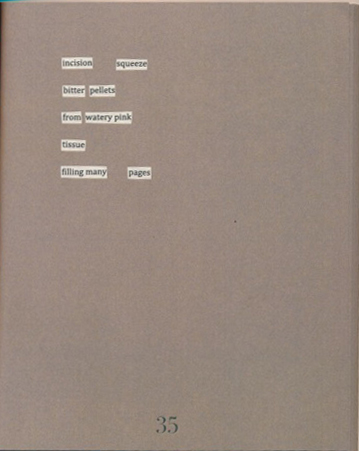

The poems in The Matrix appeared in several formats that still look alternative today. Words were crushed together; some were printed upside down. Weighty phrases were repeated within the page. Words both familiar and unfamiliar had extra spaces between the letters. While some pages had just a large single letter, on other pages the print ran to the outside edges, suggesting that it might well have continued beyond it. The Matrix challenged how a writer’s Collected Poems should look.

As for the texts themselves, they approached the limits of semantic comprehension, as Pritchard’s ideal was what he called the “transreal,” a reflection of his awareness of mystical, supernatural modernism in the visual arts. On an opening recto page was this epigraph for himself: “Words are ancillary to content.” Later in the book, the fourth page of “Gyre’s Galax” repeats the phrase “above beneath” from top to bottom, sometimes amended by the words “it” and “in.” Pritchard wanted to take poetry into a domain previously unknown, one that was indeed above beneath.

In 1971 a second Pritchard collection, Eecchhooeess, appeared from New York University Press; it is perhaps the most radical one-author poetry volume ever to appear from an American university press. Repeating many of the same challenges posed by The Matrix, Eecchhooeess is no less brilliant; its eerie sounds and typographical innovations chimed right in with the Black Arts movement of the day (Pritchard was affiliated with the literary collective Umbra).

The most unusual quality of these new reprints of Pritchard’s books is that they appear intact, with their original front covers duplicated, each totally devoid of any new preface or afterword. Not even Pritchard’s biographical note is updated; only the title and copyright pages are different. While contemporary readers might wish for more background on this utterly unique writer, to get such authentic reprinting a whole half-century later is a treat for fans of groundbreaking poetry indeed.

Click below to purchase these books through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Review of Books Volume 26, No. 3 (#103) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2021

We march and we march some more

We march and we march some more