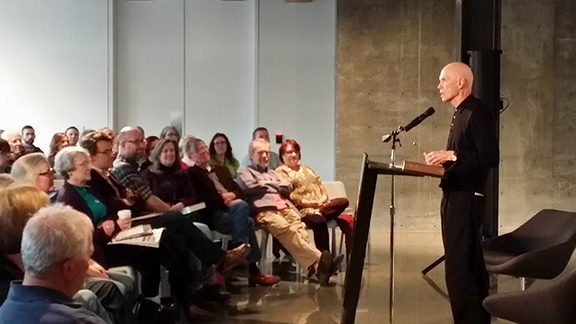

Photo by John Sarsgard

By Eric Lorberer

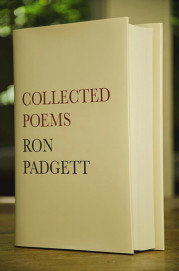

It’s a noteworthy threshold for a poet to cross, when myriad skinny volumes get assembled into a Collected Poems. In the case of Ron Padgett, the resulting tome published by Coffee House Press is 840 pages of pure bliss, taking us from the insouciant poet in his youth to the most fun elder statesman possible. Casual and profound at once, Padgett’s poems are attuned to the music of love and friendship, life and death, “how to be perfect” and “how to be a woodpecker”—all under the sign of a uniquely affable sense of humor. The book earned Padgett the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America and the L.A. Times Book Prize in poetry.

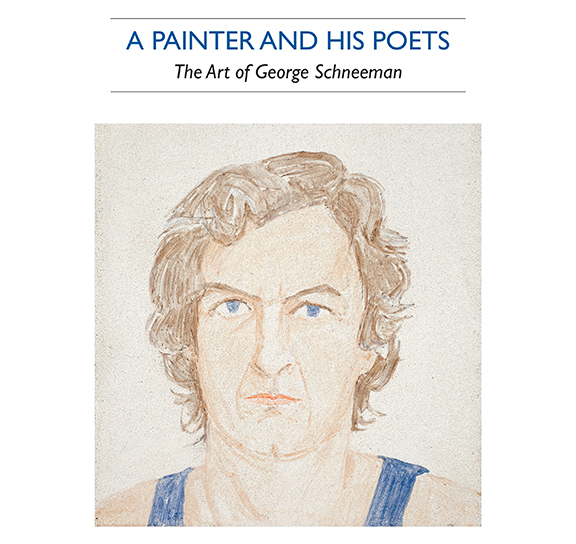

Born in Tulsa, OK, Padgett has been a long-time resident of New York City, at the center of the so-called “second generation New York School” of poets. He has written memoirs of his friendships with Ted Berrigan and Joe Brainard, has translated French poets such as Apollinaire and Cendrars, has collaborated with visual artists such as Jim Dine and Trevor Winkfield. Together with Bill Berkson he recently curated the massive show "A Painter and His Poets: The Art of George Schneeman,” which is on view at Poets House in New York through September 20, 2014. In the interview below, held by telephone during a snowstorm in Minneapolis after a reading to celebrate Collected Poems, we discuss the show, the reading, the Collected, the windows after the snow, and more.

Eric Lorberer: Let’s start by talking about your Collected Poems. How does it feel to have this tome out? In putting it together, did you notice anything about your body of work you might not have thought of before?

Ron Padgett: Physically, putting the book together was easy. Emotionally, it proved to be a lot more complicated. Initially I thought I'd just take all my books and line them up chronologically, add some poems that had never appeared in books, and that would be that. But it wasn't that. It was complicated, because after I got over my surprise at being invited by Coffee House Press to put the manuscript together, a feeling of dread set in. Maybe lurking in my unconscious was the idea that when someone's collected poems are published it means that the poet is dead. I found myself looking at my work as if I were at my own funeral.

Choosing the poems that hadn't appeared in books turned out to be rather difficult, partly because I had at least 600 pages of them. Of course the Collected was already going to be huge, so I couldn't use them all, nor did all of them deserve to be included. One day my selection of them looked good and the next it looked doubtful. Then, when I finally got that under control, I looked at the whole manuscript and had a sudden emotional downdraft and I said to myself, “So this is what your life’s work amounts to, a small cube of paper? The work is . . . okay, but it doesn't deserve to be collected in an 800-page immortalizing tome. Maybe I should tell Coffee House that they're wasting their time and money.”

Choosing the poems that hadn't appeared in books turned out to be rather difficult, partly because I had at least 600 pages of them. Of course the Collected was already going to be huge, so I couldn't use them all, nor did all of them deserve to be included. One day my selection of them looked good and the next it looked doubtful. Then, when I finally got that under control, I looked at the whole manuscript and had a sudden emotional downdraft and I said to myself, “So this is what your life’s work amounts to, a small cube of paper? The work is . . . okay, but it doesn't deserve to be collected in an 800-page immortalizing tome. Maybe I should tell Coffee House that they're wasting their time and money.”

All these daunting feelings were swept away by my wife, who on hearing my moaning and groaning told me to shape up and stop being an idiot. This snapped me out of my depression and self-doubt. I looked at the work anew, and all of a sudden it seemed pretty good! This is a prolix way of saying that putting the book together gave me quite an emotional whiplash.

Once Coffee House and I started talking about the book's design my spirits improved even more, because I love the production details of book publishing. When the book came out and I saw the first copy, it was exactly as I wanted it, physically. Now I've gotten accustomed to its existence, the way you get used to having a new dog in the house. At first it seems strange—you can't keep your eyes off it—and then it seems normal.

EL: You talked about the uncollected poems; there are about a hundred pages of them in the book. Were they poems that were in magazines but not in books, or were they from your personal files, or both?

RP: Both.

EL: Well, there's a remarkable number of them, and it’s exciting. One I like a lot is called “Poem Begun in 1961” and it gives rise to the question: when was the poem completed? There’s a really dramatic turn to what feels like something a lot closer to the present, ending with the image of Ted [Berrigan]'s journals.

RP: I didn't actually start writing that poem in 1961, but the emotional content of the poem began in 1961. I drafted it some years after Ted died, maybe around 1990. Then I put it away, as is my wont, and tried to forget about it. Subsequently I tinkered with it, put it away again for another five years, took it out again and tinkered a little more, then I finally got it to where I wanted it, but I never had occasion to publish it. So I was happy when I had the chance to put it in this book. I know it's not a monumental, earth-shattering poem, but for me it has a little punch to it.

EL: I think it’s a signature Ron Padgett poem, because it does two things really well: it plays with time in the way that poetry can do better than almost any other art form—and the passage of time is something your poems come back to again and again—and it's a poem about friendship, another recurrent and important theme for you. Your love of George [Schneeman] and Joe [Brainard] and all the many people who've been in your life, it’s amazing to see it evolve in the poetry. Is that something you're conscious of when composing?

RP: I've never seen my work through that lens, but now that you say it, it makes sense. I could probably make a small book of poems based on friendship. I don't consciously write poems about people because they’re my friends, no. I don't do much of anything consciously in writing—in poetry writing, anyway, prose usually being a different matter, of course. In fact, I’ve been working on a collection of prose vignettes about girls I’ve had crushes on, from the age of six to the age of eighteen. This manuscript is thematic and organized in a way my poems about my friends aren't. My friends get into the poems simply because they mean a lot to me. Maybe being an only child has made me want to be closer to people, to escape the isolation of being an only child. I don't know. That's off the top of my amateur psychologist head.

EL: It's true that people are presented as part of life in the same way that other quotidian things are—coffee, laundry, phone calls, etc.—so much of the ordinary stuff of life is in your poetry. Did you notice any of these motifs recurring to any interesting degree when you put them all together?

RP: I did notice one theme that kept recurring, the theme of mortality. Human mortality is more and more present as one gets deeper and deeper in the volume. It wasn't that the idea of death was absent from my earlier work, but it wasn't foregrounded. Putting this book together I realized, holy cow, there are all these poems about death, and dying, and dead friends, and I thought, “Maybe this is a too lugubrious?” Then I looked at each poem on its own, and I liked each poem, so I didn't see why I should leave them out. From a stylistic point of view, I did notice the recurrence of certain words. I ought to do a word count and see how many times I use the word little or past or maybe. Someone, many years ago—it was either Ted Berrigan or Joe Brainard—pointed out to me that I used little a lot. I saw it as a flaw, so since then I've used the word and then cut it out later.

EL: Right, that's exactly what I was talking about. It's so fascinating to put all the books in a row and then notice the through-lines.

RP: Come to think of it, I noticed that there were certain . . . let's call them moods, in the later work that I was astounded to find in my much earlier work. Or a hint of them. There were in fact certain whole poems that I'd written when I was much younger that were mature beyond my years—not very many such poems, but a couple that made me wonder, “How did I write that at that early age?” In those poems I did things that I thought I didn’t know how to do until much later. It was odd.

EL: The book begins with those early poems from In Advance of the Broken Arm, where the powerful influence of French surrealism is so pleasurably abundant—though it becomes somewhat sublimated as the work goes on. Is that an organic development, or did you make a conscious push in a less “French” direction?

RP: Almost everything that's happened in my poetry is what you might call organic. I don't do much preconceiving. The only consistent plan I've ever had is to try to break my patterns, my habits, my kneejerk tendencies in writing. If I start to sound too much like the Ron Padgett that I've read before, I stop myself. I don't want to get locked perpetually in a mode or a level of diction or a stylistic vein—what is called a poetic voice.

EL: Right, and even regarding form, it's another pleasure in such a meaty Collected Poems to see real range—for example, a lot of people might associate you with shorter poems, but then there are the prose poems and some of the longer pieces, like “How Long,” which is gorgeous, but weighs in at ten pages, so an example of what people might not immediately think of when they think of a “Ron Padgett poem.”

RP: In recent years, people have told me that they really like the accessibility of my poems. I’m glad they do, but at the same time I’m thinking to myself, “Well, that's one type of poem I’ve written, but there are others you'd find more elusive.” A lot of my poems come at you in more challenging ways.

EL: The topic of accessibility in poetry is quite complicated, and people are really concerned about it at the moment. I'm not sure why it's such an important thing now, but I hear it all the time.

RP: Yes, it's become front and center in a lot of people's thinking about poetry in the last ten or so years.

EL: Why do you think that is?

RP: I have no idea.

EL: Huh, then it's a mystery. If anything, I would have thought the culture might see a growing level of comfort with the “difficult” in art.

RP: There are many people who want poetry to be more widely read and appreciated. Hence National Poetry Month. If poetry is going to reach an audience unfamiliar with it, it virtually has to be more “accessible.” You can't take people who’ve never felt comfortable with poetry, or who are even scared of it, and say, “Here, start with this book by Ezra Pound, it's called The Cantos.” It would only alienate them. On the other end of the spectrum, there are highly accessible poems that can serve as open doorways into a larger world of poetry—from Williams’s “This Is Just to Say” to Paterson, for example. So perhaps those who want more people to like poetry feel that accessibility is important, and in such cases it is. Of course quality is another matter.

EL: Well, there are those of us who want more people to experience poetry, but that means experiencing some of the confrontation of it, the feeling that “I don’t quite get this.”

RP: I agree. Not only that, the feeling that it’s okay and even exciting not to quite “get” something. A very good book on this subject is Kenneth Koch’s Making Your Own Days. It's an anthology of great poetry with Kenneth's commentary. His main point is that poetry is a different language, like French or Japanese—you just have to learn how to understand “poetry language.” He's a master of making the “inaccessible” quite the opposite.

EL: You spoke earlier about the current project of writing “crush” vignettes, and yesterday you read the poem “Fantasy Block,” which is a great erotic poem about a supposed lack of erotic imagination. It made me realize that erotic life—and along the same lines, political life—pops up occasionally in your work; these are not major themes for you, but they appear more clearly in the context of a Collected Poems. What do you think about those two aspects of life in poetry, politics and love?

RP: Let's take them separately, starting with politics, which is easier to talk about. I agree with something that John Ashbery, I think, once said, when an interviewer asked him why he wasn’t more political in his poetry, and John said something like “I always thought that writing poetry was in itself a political act.” Aside from that, overt political content is not my strong suit. During the Vietnam War, for instance, I wrote anti-war poems that were filled with my sentiments and opinions about the conflict, and those poems were awful. The content destroyed them. I would go to anti-war rallies where poets read poems that were almost universally flat. Kenneth Koch had a similar trouble. He wanted to write something against the war, but he found that he couldn't do it well. Instead he wrote a poem called “The Pleasures of Peace,” in which he left the other kind of poem to another poet—who was actually Allen Ginsberg—who was better at writing political things.

Then there are other issues, such as social justice. I've tried. For example, around 1970 I wrote a poem called “Radio” that dealt with racial justice, specifically the relationship between blacks and whites. I think that poem worked, in an understated way. After “Radio” a lot of time had gone by before I realized I was still hesitant about writing poems about war and social justice, economic and political systems, issues I felt strongly about. So I gave myself the order—as I said earlier, I like to break my patterns—to try again and not to give up trying. Over a series of days I drafted what turned out to be a lengthy poem about cruelty and brutality, “The Absolutely Huge and Incredible Injustice in the World.” I think I was able, in that poem, to do what I wanted, to explore my feelings on the subject in a way that didn't destroy the poetic energy.

As far as the other thing, you began talking about eroticism and then switched over to love. There are a lot of love poems in my work. I'm a rather sentimental, soft-hearted person, when you get right down to it. So writing about love or having it infuse the poems that I'm writing has never been something I've set myself to do, except when I write a poem for my wife, for an occasion, such as our anniversary. As far as eroticism, there's a certain amount of it in this book, but it's very rarely on its own, separate from love and the emotional feeling of love (as distinct from the sexual feeling of love). To me, eroticism has always been combined with emotion, except when I was a young child—I can't remember any erotic impulses I had toward any girls—but I was able to have crushes on girls, even later, without wanting to have sex with them. It’s fun to have a crush on somebody, even one that lasts only fifteen seconds. In New York I can go down the street and have a crush on somebody coming toward me, and then she walks by and the crush disappears. It's quite pleasant.

Let me add that there's a poem of mine called “Sweet Pea” that’s essentially a long list poem, a song of praise in which the beloved is compared to flowers. I began to write that poem out of a fascination with the names of flowers. In looking through a seed catalogue in 1970 I was amazed by the beauty of the names of different varieties of flowers—some of them were quite imaginative. The Giant Señorita! I got excited about that and wrote a first line, “You're sweeter than the sweet pea,” which set me off. I drafted the poem in one sitting. The “you” in the poem was a particular person I had in mind, my wife. But later in the poem, I got lost in this garden in my head, and the “you” morphed into girls I'd had crushes on in high school, and actually at one point the “you” figure was my mother. Then it switched back to my wife. I wasn't doing this on purpose, but in the back of my mind were these different female images. Writing “Sweet Pea” was an intricate and exhilarating experience, and I felt very happy when I finished it.

EL: Well, that's definitely the desired result of any eroticism.

RP: Uh, yes. Again, there are parts that are more overtly erotic, then there are parts that aren't at all. They're about attraction and affection and warmth and respect for a beloved girl or woman.

EL: So, as you alluded to earlier when we were talking about choosing the uncollected poems, this Collected Poems is not actually a Complete Poems. Of course this would be true anyway, as it hits a chronological stopping point and you’re still writing, but also it doesn't include two things which I think are key in your history as a writer: collaborations and translations. Let’s start with the many collaborations you've done with other poets and visual artists; what sort of role do you think they played in your artistic development?

RP: It’s fairly safe to say that they loosened me up and made me more comfortable with not being in total control over what I was doing. In fact, it made me very happy to not be in control of what I was doing. I don't mean out of control. If you write a line and then your collaborator comes along and writes another line that changes the meaning of what you've just written, then you write a third line that changes the meaning of what he or she wrote, you get a multi-voice, push-pull situation in the writing. One can internalize that procedure to some degree and then surprise oneself when writing solo.

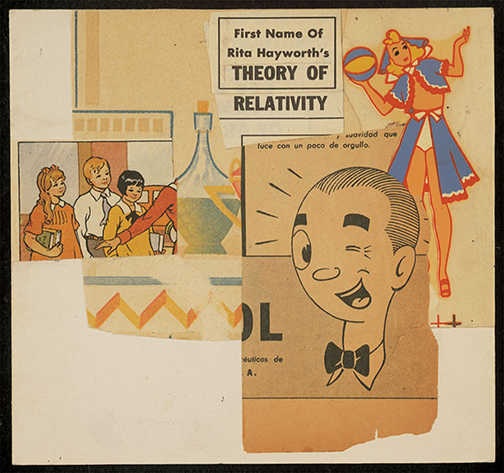

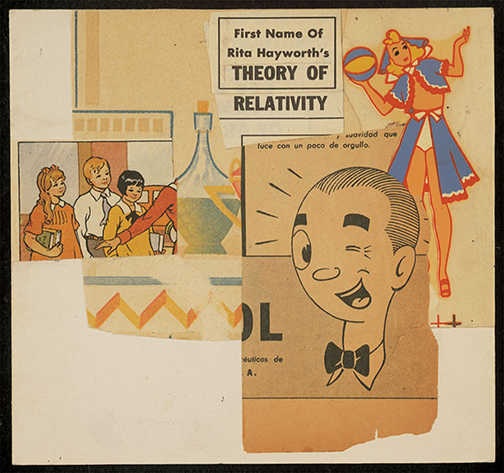

Rita Hayworth's Theory, ca. 1970-71, collaboration by George Schneeman and Ron Padgett

Also, collaborating made it easier for me to write comic poems. Ted and I were always cracking up when we were collaborating, which made me more willing to do that on my own. To some degree the same applies to working with artists, although I've collaborated in different ways with different artists. Working with Alex Katz is not the same as working with Jim Dine, or Trevor Winkfield, or Bertrand Dorny, or Joe Brainard, or George Schneeman, because each artist brings a different feel and style, which has required that I adjust to each one’s modus operandi. Some artists have been flexible about adjusting to me as well, but flexibility doesn't make their work any better or worse, it's just means that they're different people, and I have taken a lot of pleasure in working with all of them.

I did most of my collaborative work with George Schneeman, with whom I did at least three hundred pieces. There's a big exhibition of George's collaborative work with poets opening at Poets House in New York on April 22nd—and it's going to be up for five months—a show of about a hundred pieces of collaborative works and portraits that George did with Bill Berkson, Anne Waldman, Ted Berrigan, Larry Fagin, Maureen Owen, Michael Brownstein, Peter Schjeldahl, and me, among others. It's quite an exciting show. (That’s a commercial I just threw in.) But anyway, in general, working with artists and other poets has made me aware that there was a bigger “me” that I hadn’t been quite aware of. Plus we had a good time. It’s so much fun to write, for example, with a big brush on a giant piece of paper and to help create visually attractive and surprising objects, which is not what you normally do when you're writing a poem. It’s wonderful to create these pieces with artists.

Cover of Poets House catalog. Click image for more info.

EL: Besides that general feeling of being loosened up, and maybe being more dialogic than when you're composing by yourself, were there any collaborations that had a direct impact on something you were writing solo?

RP: I don't think so, not very much. I can think of one exception, working with Trevor Winkfield on a couple of little books. One is called How to Be a Woodpecker and one is called How to Be Modern Art, in both of which I suggested some kind of poem, or the direction of a poem, and then Trevor did some drawings for it and showed them to me. Looking at his drawings then made me change what I'd done. So in that case, yes. Otherwise, the influence that collaborations with artists have had on me would be more general, along the lines I described earlier.

EL: If you had to put together a Collected Collaborations of Ron Padgett, would the process be similar to what you were talking about earlier, narrowing the six hundred pages of uncollected poems down to the one hundred pages in the book? Would it follow that same model of evaluation?

RP: It would because, as with all of the work I've done, some of it is good and some of it isn’t. Not everyone is at the top of his or her game all the time—you can't be. Some of the collaborative poems I wrote turned out to be more silly than anything else, and I wouldn’t want to foist those on the public. The same with art: some of the pieces George and I made were terrific, some were really good, some were pretty good, some were so-so, and some were duds. The two of us usually worked together spontaneously on the same surface at the same time, sometimes creating five or six pieces simultaneously, so we didn’t expect everything to come out perfect. In fact, we weren’t even thinking about perfection, thank god. We were just working. So yes, I would select, for sure.

EL: Coming back to translation, much like I was talking about with those early poems and their affinity for French surrealism, it seems to me that your history of translation, especially with Apollinaire and Cendrars, must inform your own work. How does that play out?

RP: It seems more than likely that the translating of poetry is going to rub off on the translator if he or she is a poet. I've been putting together the translations of Apollinaire's poetry that I've been doing for a long time, and New York Review Books is going to publish it in a year or so. (That’s another commercial.) There's a certain kind of syntactical energy in some of Apollinaire's poems that I think did influence certain more recent poems of mine. Also, his work has a lyricism that is very attractive to me. Maybe it’s encouraged me to give freer rein to sound and the lyrical in my own work. I don't know, it's hard to measure that kind of influence. I do know that I've never successfully translated anything that didn't resonate with me as a poet. There are a number of good French poets whose work hasn't been adequately translated, or translated at all. I see how good it is, but I can't figure out how to make it good in American English.

EL: Indeed, it's its own alchemy, and a very complicated one.

RP: A good example is Mallarmé's poetry. My attempts at translating it have been valiant but feeble. When I was in college, I tried translating Verlaine, but the result was flat. Reverdy is another example. I love his poems, but I have never, with a few exceptions—mainly his prose poems—felt that my translations came close to the originals. He uses a simple vocabulary and simple syntax, but he favors certain words that are hard to translate, such as on. Trying to find the right solution in English is frustrating, because it doesn’t exist. Also, there’s a musicality in his work that gets lost in most translations of it. It's interesting: he's a poet I initially thought I could translate well, even though his sensibility is quite different from mine. I admired him a lot and thought I could learn something from him. I guess one thing I learned was that I'm not very good at translating his poems!

EL: Certainly of the three you just mentioned, his work seems the most likely where you'd find a natural affinity there, as opposed to somebody like Mallarmé.

RP: Oh, a minute ago we were talking about my collaborations with other poets, and I just remembered that I did assemble a collection of them, in a book called If I Were You. It was published by a small press in Toronto called Proper Tales Press.

EL: On the topic of both collaboration and translation, maybe we could chat for a second about the chapbook Rain Taxi published by you and Yu Jian, Three Blind Poems. In a strange way it’s both a collaboration and a translation, and also resists those modes at the same time.

EL: On the topic of both collaboration and translation, maybe we could chat for a second about the chapbook Rain Taxi published by you and Yu Jian, Three Blind Poems. In a strange way it’s both a collaboration and a translation, and also resists those modes at the same time.

RP: Writing those poems with Yu Jian was bizarre and interesting and amusing and scary all at the same time. Yu Jian does not speak English, and my Mandarin is severely limited. But going up on a mountaintop in Vermont with him and passing a notebook back and forth, with Yu Jian writing in Mandarin and me in English, interlinear fashion, not knowing what the other person was saying—I can't think of anyone’s ever having done that. It was a step beyond exquisite corpses. So that in itself made it interesting to me. Then when I had his Mandarin translated into English, by Wang Ping, I was stunned by how well our lines fit together—not perfectly of course, but with surprising continuity. I went back and smoothed out some of the transitions and revised things a bit, but not a whole lot. Are those great poems for the ages? Probably not. But I think they're worthwhile as an experiment. It would be interesting to see other poets try it as well. Earlier I spoke about collaborating with Ted Berrigan and how it stretched me open. Well, collaborating with someone who doesn't understand your language nor you theirs stretches you open even wider, into a sort of very large free fall.

EL: Right, but you're with that collaborator and you trust him. You have a relationship.

RP: That was very important. It would have been rather uninviting to do that with a poet I didn't know. Yu Jian and I were friends—for some reason we took to each other immediately when we first met. We’re comfortable with each other, which is unusual for people who can't talk to each other! I've never understood why Yu Jian and I like each other so much, but we do. We trust each other. It's a joy to know a fellow poet on those terms.

EL: The published chapbook is definitely a testament to that emotion.

RP: We were happy to be up there on that mountain, scribbling away, not knowing what the other guy was saying.

EL: I think the last question I'll ask you is about the act of giving a poetry reading. It was such a pleasure to hear you last night, and also to hear work spanning such a long time period and different modes. I've been thinking about poetry readings as not necessarily some after-the-fact packaging of something already written, but as part of the artistic process. I wonder if that's something you think about at all—if the act of giving a reading is some kind of artistic opportunity for you.

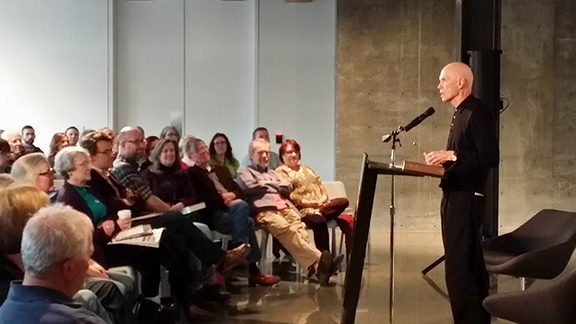

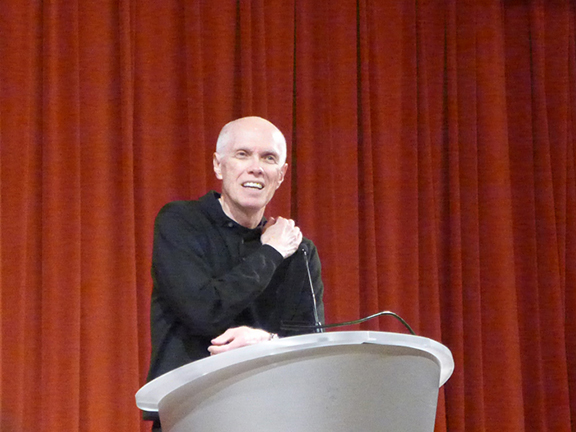

Ron Padgett reading in Tulsa, April 1, 2014, photo by Kent Martin

RP: I do, very much so. I don't do cookie-cutter readings. Each reading I give is constructed. It's constructed on my fantasy of the venue, the audience, the time limit, and what I happen to be interested in at the moment. So for instance, before reading here in Minneapolis, I read in Tulsa. Having been born and raised there, I had a very different sense of who that audience would be. In constructing that reading I realized I was picking poems that were related to Tulsa, sometimes explicitly, sometimes obliquely, so I went ahead and planned a very “Tulsa” reading. Then I had to cut the selection to fit the allotted time, and then arrange the poems in a sequence that made aesthetic sense to me, just like arranging the poems in a book manuscript.

Part of the pleasure of giving a reading comes from the rapport between the audience and the poet. I don't want to get mystical here, but there's an energy flow that begins with the poet, and the energy goes out to the audience, and they're energized, and then they return that energy to the poet. As someone standing up there alone, facing these people, I can feel that rapport (or its absence). If they laugh at something funny, obviously that's an indicator, but there's something else. It’s when the audience is not twitching, or coughing, or getting up and leaving, when they're all focussed on you, attentive. They're there. They're with you. This allows the energy to flow back and forth. It's very pleasurable, and makes me feel like I'm sitting in my living room reading to my wife. It becomes personal, it's not just, “Oh, here's a poet come to town to show off.” It becomes intimate, and when that's happening, as it did for me last night, it makes the reading a breeze. I don’t have to struggle or push to get the work across. It goes across by itself. I love it when that happens. So yes, your question is something I think about.

EL: It's a great answer and one that I'll be happy to publish. I think that too many poets don't see giving a reading as part of the aesthetic experience, and it's such a missed opportunity.

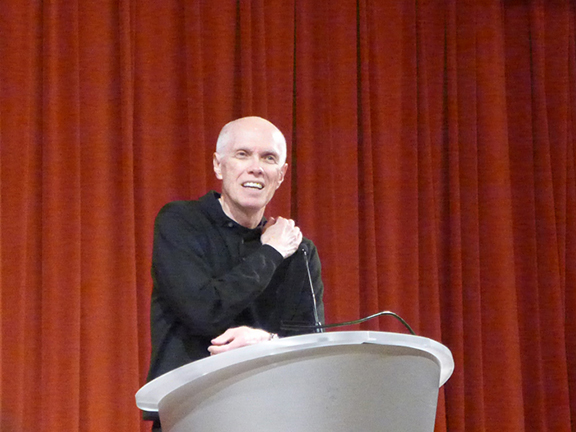

Ron Padgett reading in Minneapolis, April 3, 2014

RP: I've never become jaded about giving readings. After last night's, I still have the residue of that good feeling, which made it easier for me to answer your question. It's interesting, right now I'm propped up in bed here in this spacious hotel room, with the curtains drawn open on big wide windows through which I see the Wells Fargo building across the street. There are rivulets of melting snow running down the windows—I've been following them with my eyes throughout our conversation. It made me think of Apollinaire’s poem “It's Raining.” The words of his poem are arranged like streaks of falling water, running down the page, so when you were asking about translation and I mentioned him I was actually sort of seeing one of his poems enacted on the windows of my hotel here.

EL: I think a hotel window is a great place for an Apollinaire poem to appear.

RP: The accepted view is that his poem is a visual representation of falling rain. I thought so too for many years, until I read a comment by an Apollinaire scholar saying he thought it was really rain running down a windowpane, which struck me as bang-on true. And I thought, “Why didn't I think of that?”

Click here to purchase Collected Poems at your local independent bookstore

Bai Hua

Bai Hua

Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé

Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé