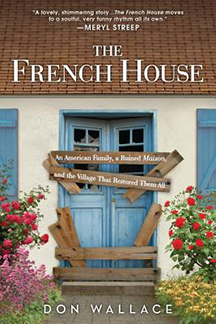

An American Family, A Ruined Maison,

An American Family, A Ruined Maison,

and the Village that Restored Them All

Don Wallace

Sourcebooks ($14.99)

by Linda Lappin

Imagine an old house—a ruin, really—on an island across the ocean waiting for you to claim it. For many people such a proposition would be pure folly, but for others, an irresistible enticement. So it was for Don Wallace and his wife Mindy, two struggling writers from Honolulu who received a letter from a friend in the early 1980s, summoning them to a small island off the coast of Brittany where a bargain piece of real estate had just been put up for sale. Nearly thirty years would pass before their property becomes habitable, and in the process they make a family, lose a friend, and become fixtures of a foreign place, as Wallace recounts in The French House: An American Family, A Ruined Maison, and the Village that Restored Them All.

The couple had first visited the island while returning from a long stay in Paris, where, with portable typewriters in tow, they had failed to fulfill the writer’s dream of mingling fame and café life. Their novels remained unsold, but Mindy had passed her bar exam and it was time to decamp. Before flying home, they took the ferry out to Belle Île where Gwened, a former professor of Mindy’s, lent them her house for a few days. It was love at first sight for the Pacific-born couple. They respond viscerally to the island’s surfing potential and its rough magic, which Wallace celebrates in sinewy prose:

Cliffs crumble, dark masses of seaweed cover the beaches, rows of cypresses fall, ripping up the earth with their roots. Fishermen and tourists are washed away to become crab bait. Early in the morning after a storm, the island tries to convince you that its bruises mean nothing, calling your attention instead to the sun-kissed mists and drifts of spume, taller than a man, that collect in the coves and creeks. The shadow of violence in her eyes haunts you, however. Never turn your back on the sea.

Gwened leads them by the nose on an adventure spanning decades, not a moment of which they come to regret. “The village will be good for you, and you will be good for it,” she promises. The house needs them; the villagers have even taken a vote that they want the Wallaces and not anyone else to buy it. The argument convinces them and they soon sink their scanty savings into a 155-year-old hovel with treacherous floorboards, a dangerous roof, and the inside walls covered in black moss. Mindy throws up when she first sees the place—she’s pregnant—so they give instructions to a contractor and return to New York, where they start a family, slave away at their jobs, hang a map of the island by the bathroom door, and dream of their house by the sea.

Circumstances are such that they can’t visit Belle Île very often to see how the restoration work is going; meanwhile, the dollar is falling. Friends at home object: Why have a house in France if you can’t go there? Gwened and the villagers complain: You’re taking too long to fix this eyesore up! And house-hunters from Paris accuse: You are depriving French citizens of their right to a house in their homeland. But the Wallaces hang on, and board by board, penny by penny, the house is made habitable; one month out of every year, it shelters their most cherished dream.

Village life vignettes, the sensual celebration of island pleasures, eccentric neighbors, cuisine, beach life, natural history—readers will find a smattering of all that in these pages, but it’s the story below, like the unshakeable foundations of the house itself, that makes this such a satisfying read. In the end it’s a story about how places and dreams of places take possession of us, teach us about them, and live through us—until it’s time to relinquish our stewardship and pass on the keys.