Prose Poems on Silent Film

Prose Poems on Silent Film

Gregory Robinson

Rose Metal Press ($14.95)

by Jay Besemer

In September 2013, the Library of Congress published a report by film scholar David Pierce entitled The Survival of American Silent Feature Films 1912-1929. This report (available as a PDF online) details the startling and dismaying loss of over 7,600 original silent features through medium decay, fire, breakage and actual misplacement. Those lost films comprise the majority of the silent features produced in the United States, which means that only a very few complete silent films are now accessible to U.S. scholars, filmmakers, fans, and the general public. Those who love silent film, or want to love it, have to find our own ways to meet it. Sometimes, meetings of that sort occur in unexpected venues.

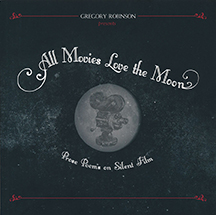

Keep this in mind as you enter the darkened theater of Gregory Robinson’s All Movies Love the Moon. This astonishing square-format collection of prose poems and images goes far beyond imitation or simple ekphrastic reconstitution. Somehow, Robinson manages to craft a film-festival in poem form. It’s not just that the poems are strongly visual, though that’s certainly true. Here’s a vibrant example, “TESS OF THE STORM COUNTRY (1922)” in its entirety:

Invisible oceans of warm and cold air collide, turning cobalt and blocking the sun. Tess raises her arms—what comes next lets us live.

Elias loves Orn because Orn is poor and Elias needs poor people to clarify what he is not. Elias’ language of love is shaking fists and harrumphing until his monocle falls loose and he is forced to retrieve it.

Orn loves Elias too, though he would never admit it. Elias is confusing and distant, right on the edge of actually living. Orn pities him, but when Elias comes to visit, Orn always has a shotgun in hand.

Tess raises her arms. She is a cloud, born to shelter, hold, and break apart, to stand impossibly between these two foes. She sees the secret between them, their deep mutual affection, and knows it is how the world works, that no enmities are forgotten in another’s need, just redirected, sent upwards, crashing into the cold air and sending down the rain.

The tension between narrative and image is strong in a poem like this, and it’s easy to imagine the same tension in early silent film. Of course, not all films need to be narrative-driven, and narrative poetry is certainly not the only type of poem to be made. Prose poetry seems the perfect form in which to explore the problem of narrative in poetics, as well as the problem of narrative in cinema.

Like the other poems, “TESS” takes its title from that of an actual silent film, and the poems appear in “chronological” order according to the release date of the film each is named for. This kind of organization helps us glean an unofficial, poetic history of the silent film genre. There’s also a careful, quirkily informative introduction, but readers should not expect a straight history lesson or film studies seminar. After all, it’s a book of “prose poems on silent film.“ That ambiguous “on” invites us to make an imaginative leap; although we are reading poems on a page, these verbal works might conceivably be made on film, literally. Even the supple semi-gloss paper on which the book is printed offers a tactile analogy to film. These media/genre blurs resonate nicely from the book’s conceptual core through its content to its realization as an object.

On the facing page of each poem is a figure reproducing or derived from “screen shots” of one of the movie’s title cards. These cards combine text and graphic, or text and film image, to clarify or narrate more or less what’s happening onscreen. Robinson’s funny, ironic, informative captions illuminate or complicate these verbal images, effectively providing title cards for the title cards presented. If “title cards were silent film’s Statler and Waldorf,” as we are told in the introduction, Robinson plays a great Fozzie Bear, commenting on the commentary.

Title cards, readers soon learn, were an art form unto themselves. As early 20th-century cross-genre visual poetry their value is clear, and much could still be written about their influence on poet-artists who came to use similar media—for example, Czech Surrealists Jindrich Heisler and Toyen, whose collaborative collaged photo-poems look quite a bit like title cards. The connection between the poetry on the screen and the poetry on Robinson’s pages becomes delightfully evident as the book progresses.

Title cards (and their authors) finally emerge as the secret heroes of All Movies Love the Moon. The author’s affectionate admiration for some of the best title artists—whom he names for us—feels right for a book filled with wistfulness and fierceness. Here’s one of Robinson’s title card captions, which themselves comprise a sort of stealth prose poem form:

FIGURE 29: Once I drove six hours to dig around a cemetery to find [title artist] Ralph Spence’s grave, crossing state and vastly darker lines.

It’s the perfect teaser. What lines? What states? Six hours in a vehicle, on an obsessive quest for a gravesite, sounds like the perfect silent film plot. Ultimately, All Movies Love the Moon works on both poetic and cinematic levels. The contagious delight of discovery, catalyzed by these poems, may well inspire a new level of interest in silent film (at least among readers of poetry). All Movies Love the Moon gives a new and unexpected meeting-place for readers and film fans to get acquainted with the form. It’s a different way to preserve a cultural treasure, but a highly effective one.