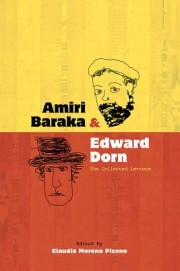

Edited by Claudia Moreno Pisano

Edited by Claudia Moreno Pisano

University Of New Mexico Press ($59.95)

by Eliza Murphy

Intended “if not to overthrow, to at least disrupt the status quo of preconceived notions in American letters” by seamlessly incorporating snippets of historical details between the missives of two American literary figures, editor Claudia Pisano hit her mark. Instead of an epistolary, she’s created a narrative assemblage with artfully selected materials whose backdrop never overshadows the shifting tones contained within the correspondence between poets Ed Dorn and Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones).

Complete with misspellings, quirky punctuation, complaints about the weather (which they often attributed to nuclear bomb testing), money woes, relationship difficulties, and other details that reveal their personal turmoil and triumphs, the correspondence took place from 1959-1965, just as the poets were establishing themselves as artists. Arranged chronologically, the letters show the development of two avant-garde poets confronting race, the necessity to break free of formal constraints established by mainstream academia, and their different approaches to dealing with official versus actual history. Moody, testy, exciting and exasperating, the letters show two individuals forging their paths during a time of incredible cultural upheaval. At times contemporary readers will want to pitch the book across the room because of the intense misogyny (“Man is she cruising for a bruising”) and homophobia, though to be fair, we are still only beginning to chip away at the hateful currents such comments reflect.

From the excitement and enthusiasm expressed in their letters, they were maneuvering during a heady time. Everything was up for grabs. Post-World War II malaise had no place in a world encumbered with the Cuban Missile Crisis, nuclear weapons testing, the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights movement. Neither Dorn nor Baraka led sheltered lives, yet their letters reveal the progression of radical stances that replaced the glaze of innocence as they became more aware of the larger world. They were both coming into their own as writers during incredible artistic foment across disciplines. Jazz was informing poetry and painting. Politics seeped into theater. Charles Olson and other Black Mountain poets had liberated poetry from academia, freeing language and challenging mainstream values. Like-minded poets found one another, celebrated one another’s resistance to mainstream academic poetry in letters, lit mags, and at public readings.

Baraka grew increasingly militant as he rejected the white New York culture he knew and came to identify with Black Power. Way out in the rural American West, Dorn honed in on Native American issues, as well as the myth of the frontier. As each wrestled with the monkeys on their backs, they sought intellectual companionship through (what is now considered old-fashioned) letter writing.

Both poets actively resisted writing the sort of poetry codified with prizes and posts as poet laureates. (Baraka was removed from his brief stint as the New Jersey poet laureate for making remarks considered anti-Semitic after 9/11). Poetry was not a pretty, risk-free arena to lyricize, but a place to take action, to wrestle with ideas, to engage the head as much as the heart. Pisano refers to Dorn and Baraka as “outsiders,” presumably because they deliberately defied convention, eliminating their potential to win major prizes like the Guggenheim Fellowship (which Olson won twice, as they jealously point out). Yet, they were both engaged in a diverse community of experimental writers who actively supported one another by publishing their work in lit mags and arranging public readings.

A lively outgrowth of the series Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, this volume adds another layer of scholarship that offers a glimpse of two men devoted to creative and intellectual pursuits during an era marked by imaginative resistance to institutionalized values. Pisano deftly contextualizes the tumultuous backdrop against which these two poets maintained their long distance friendship while establishing themselves as writers. In so doing, these two jazz-infused poets emerge as feisty, driven agitators whose heretical stances will undoubtedly continue to vex and delight readers and scholars alike.