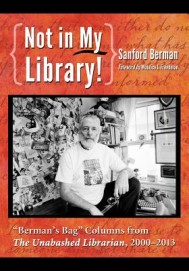

“Berman’s Bag” Columns from The Unabashed Librarian, 2000-2013

“Berman’s Bag” Columns from The Unabashed Librarian, 2000-2013

Sanford Berman

McFarland ($35)

by Kelsey Irving Beson

The many laudatory blurbs on the back cover of Not in My Library! variously describe Sanford Berman as “a modern-day Diogenes,” “an advocate for the disadvantaged,” “fire for the mind,” and “the biggest mensch in librarianship.” Berman is a noted (some might say notorious) Twin Cities librarian, muckraker, activist, and all-around loudmouth; he agitates stridently for everything from rational cataloging practices to homeless rights, and has been a thorn in the side of the various authorities with which he has been clashing for over half a century. Not in My Library! collects Berman’s columns from the magazine The Unabashed Librarian from 2000-2013. These articles include excerpts from a multitude of sources, such as correspondence, editorials, newspaper articles, zines, freethought publications, and alternative and mainstream library magazines. The breadth of Berman’s interest is apparent here—he has a librarian’s curiosity, a trait informed by decades of subject cataloging.

One of the highlights of Berman’s career has been to revolutionize Library of Congress Subject Headings. Cataloging-related issues might not seem like such a big deal to non-librarians, but a bad bibliographic record can render a book impossible to find, even with keyword searching. For example, Berman agitated for years until the heading “Vietnamese Conflict” was finally updated to “Vietnam War” (in 2006!). Understandably, headings can become outdated, but some are so ossified that they seem deliberately obfuscatory, such as “Canada. Treaties, etc. 1992 Oct. 7” to refer to what any normal person would call “NAFTA.” Despite the fact that he is now eighty, Berman comes off as really hip: he pushes for new subject headings on everything from cyberchondria to mountaintop removal (and he’s the reason that there is a Library of Congress authority record for “strap-on sex”). These articles document his effort to make bibliographic records more humane in terms of both equitability and usability. Berman’s open letters to the Library of Congress push a breath of fresh air into the world of librarianship, which is often insular and slow to change.

The Library of Congress is not the only organization with which Berman has butted heads—Not in My Library! also documents disputes with entities such as the Hennepin County Library and the American Library Association. Points of contention include Banned Books Week (which Berman insists is a farce), rights for marginalized library patrons such as the homeless, and hierarchical library management, which he likens to a “medieval fiefdom.” The thread that ties these articles together is Berman’s deep commitment to activism, which borders on workaholism. A hardline reformer who doesn’t want to hear that things are better than they were, he only cares about the gold standard of how things should be. The only negative thing one could say about this book is that it can occasionally feel monotonous—a lot of the columns cover the same territory. However, if they are repetitive, it’s because the same issues keep popping up over and over. If anyone could single-handedly solve these problems, it would be Sanford Berman, whose incredible, lifelong commitment to people-oriented librarianship shines through every page of this book. Why do libraries maintain their relevance in a digital age? Berman best sums it up himself: “Is there anything more satisfying than making it possible for people—irrespective of class or appearance or age—to learn, to laugh, to reflect, and to relax in their own public space and without being exhorted to do this or buy that?”