but if you had heard of it, you'd really enjoy reading it, which is why this unusual book review, Rain Taxi, continues to exist against what truly are the longest of odds

by Keith Harris

Watch your head.

To reach the office, you've got to duck. Yes, that means you, no matter how accustomed your fingertips may be to flailing uselessly at the topmost kitchen shelves or however familiar your unbowed head may be to slipping unscathed through the lowest doorways. The ceiling in this place dips low enough that even a five-and-a-half-footer like me can't enter upright. If you're given to romanticizing the mighty efforts of those who toil for their art--and what respectably employed bachelor or bachelorette of the arts, in his or her most self-hating moments, doesn't indulge such fantasies of gainful poverty?--you might be entranced by the cramped possibilities.

Yeah, well, daydream on your own time, 'cause it's just an office. When you get up the stairs the ceiling raises back up to full human height, and there's nothing mystical about the two computers that sit on two desks at right angles to each another, where words are processed and text boxes filled and images cut and pasted. Nothing unusual at all, except maybe the sheer number of books surrounding them. Like the small yellow South Minneapolis house of which this is an attic appendage, the office is compact but neat, overfull but not claustrophobic. There are books here as in the rest of the house, books that loiter obediently on their shelves rather than sloppily spilling over to consume their environment, books so plentiful that you wouldn't have time to read a fraction of them even if you weren't preoccupied with publishing a quarterly book review. And that's what Rain Taxi is. And this is where Rain Taxi comes from.

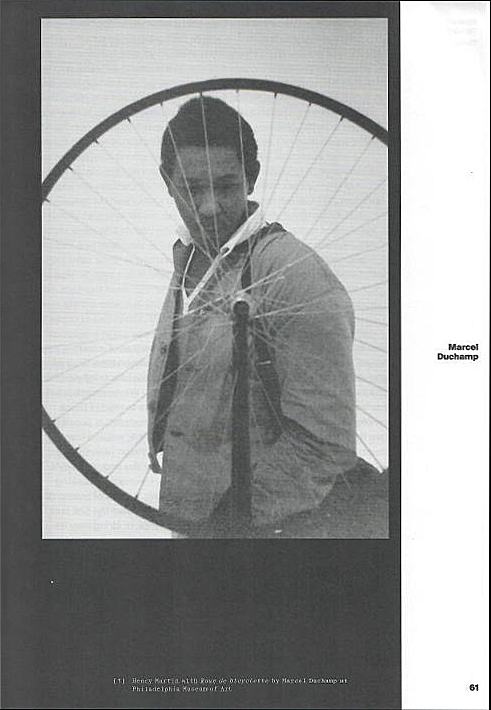

Four times a year, Rain Taxi compiles 50-odd pages of reviews: reviews of books that seem to range from the merely uncommercial to the downright obscure, reviews of books whose audiences vary from the merely specialized to the all-but-imaginary. But there are readers who want to find out about the poetry of Charles Borkhuis and the collected letters of Marcel Duchamp, and they want to do it in one sitting. There are readers who lust for a journal that highlights an interview with the surreal "storytelling poet" James Tate and a reconsideration of the "16th-century subversions" of Rabelais, as the cover of the most recent Rain Taxi advertises. There are readers who pick up the newsprint quarterly at St. Mark's in Manhattan or City Lights in San Francisco, just as locals do at the Ruminator in St. Paul. There are even readers who subscribe from Czechoslovakia and Korea. And there are enough of them--just enough perhaps--that Rain Taxi, lifted by a gentle dribble of ad sales that feeds into a sporadic trickle of grant funding, has remained afloat for five years now.

When I say Rain Taxi, I mean Eric Lorberer and Kelly Everding. They didn't start the magazine; Randall Health and Carolyn Kuebler midwifed the first issue, and nurtured Rain Taxi in its infancy. Unpaid interns drift regularly across the masthead. Fifty or so writers contribute their reviews each issue--that's contribute, not "sell," since said scribblers, whether they're still a quarter shy of escaping the U or taking time off from their eighth novel, go as unpaid as the interns. But despite the efforts of these volunteers, it's Lorberer and Everding who make sure the journal exists and who'd be out of a job if it didn't.

"Of course, there's the aesthetic issue--the pleasure of holding actual paper--but there's also the social issue, we want to reach readers from different segments of society, who might not have access to the Internet."

That's Eric Lorberer speaking about why Rain Taxi courts the added expense of remaining a print journal rather than merely existing online. This is his attic.

When Lorberer says Rain Taxi exists "to provide an alternative outlet for book reviewing," one might hear the flat, pointed prose of the grant proposal. When he continues, "Like the book industry in general, book reviewing was increasingly in the clutches of corporate powers and that didn't allow a lot of space for different voices to be heard, and also for certain kinds of books to be reviewed," you might hear the earnest, marginalized tone of the crusader. And you'd be right in both cases. Lorberer is a strange mix of the insistently pragmatic and the unyieldingly idealistic.

Lorberer is a curly-haired fellow in his late 30s who speaks in the even tone of the committed and who proselytizes without attempting to argue. The implicit assumption being: If his own evident commitment doesn't sway you, you must tarry beyond the reach of salvation. "Our mission is to reach as many people as possible and turn them on to books they wouldn't otherwise be aware of," he continues. All you've got to do is reach them.

"Eric is one of the true believers," says Josie Rawson, who lives across the alley and sits on Rain Taxi's board of directors. (Rawson is also a former associate editor at City Pages.) "He took a vow of poetry. He's got a vision of literature making the world safe for people."

It's safe to assume that Kelly Everding shares Lorberer's zeal, since she's his business partner as well as his domestic partner of some 14 years. She's quieter about the mission, though.

A recent afternoon visit finds Everding, a woman with long straight hair and pointed features, sitting in the attic finishing a flyer for the Twin Cities Book Festival. This one-day affair, to be held at Open Book in downtown Minneapolis on Saturday, October 27, is the first of its kind since the small, unsatisfying book fairs held in Calhoun Square in the mid-Nineties. For eight hours, the various rooms and crannies of the Open Book will be filled with panel discussions, readings, book sales, and book-arts demonstrations, capped that evening by a keynote reading by poet Robert Creeley.

As with so many book-related events, Rain Taxi has taken an active interest in the festival--Lorberer has been working closely with event organizers Jana Robbins and Tim Schwartz. In fact, the mag's sponsorship of the event marks its five-year anniversary, a testament to how far Rain Taxi has come since its inception.

In early 1996, a small, not dissimilar attic apartment not far away began to shrink. Two hundred copies of a fledgling journal called Rain Taxi showed up in the Harriet Avenue living room that Randall Heath and Carolyn Kuebler shared. Soon, the journal spread through the halls. Four times a year, their guests arrived. With each print run, the number of magazines doubled, and the space in which the couple lived dwindled.

"We'd line them up along the hallway," Kuebler remembers. "Soon it was impossible to move."

The initial idea had been to create a small press, though that notion quickly changed. Heath was working at Half Price Books, one of those morgues for the publishing industry where countless new books no one will ever read meet their lonely, remaindered deaths.

"We realized as we were fishing around that there are so many damn books out there already, it seemed kind of pointless," says Heath." Why contribute to this great mass of books that already existed? Why not try and review some of these books, and try to build a readership?"

Eric Lorberer showed up for the first issue with a review of a collection of Denis Johnson poetry that no one else wanted to publish. He was sucked into the Rain Taxi organization quickly afterward. To qualify as a nonprofit organization, Rain Taxi needed a board of directors, which meant they needed a third partner. When an early collaborator broke away, Lorberer was enlisted.

All the clichés of home publishing in the digital age helped spawn Rain Taxi. Suddenly, the ubiquity of PCs and easy layout software meant anyone with more spare time than inhibition could reel out limitless broadsheets about his or her obsessions. The Internet meant you could publish distant writers you might never have spoken to, even by phone. The crew survived on the adrenaline of a new project.

Heath fondly remembers the spontaneity of those early excitable years. "We scheduled an interview with [avant-garde novelist] Rikki Ducornet, so we jumped in my truck and drove to Denver," he recalls. "We had dinner with her, interviewed her. Here was this excuse to interact with someone whose work you admire."

But beyond giddy moments like that there was a world of work to do. They had to edit. They had to write. They had to design. And when they dropped an issue off at the printer, their labors had in some ways just begun.

"Around Christmas time, we had 150 boxes, at least, to take to UPS," remembers Kuebler. "They wouldn't pick them up, so we had to rent a U-Haul. We drove them to the UPS countertop, and of course there was a huge line already. The manager was so mean to us: We'd already taped up the boxes, but she whipped out a tape gun and told us we were going to pay for extra tape."

This form of cooperative labor fueled every aspect of Rain Taxi's existence. It was a necessity for tackling distribution. And when it came to the much-loathed task of selling ads, each crew member would take turns hassling publishers as long as she could stomach the job, then pass the phone along to the next person. But in the more subjective realm of editorial tasks, such collaboration seemed downright perverse if not completely counterproductive.

"We would group-edit reviews," recalls Heath. "We would sit down together with a piece--we did this for almost two years, a year and a half at least. It was an ideal we strived for. It was about not establishing a hierarchy."

It was also a good way to waste valuable hours dickering over a slight change in authorial tone. For anyone who doesn't spend much time wrangling over words, it's difficult to imagine how impossible that ideal might be. Consider such democracy extended to the sidelines of a football game. Or, better yet, imagine the infield convening on the mound to debate the relative merits of each upcoming pitch.

"I don't have the same aesthetic as Eric," Heath says simply. "For me it was more of a question of audience, a tone that would cross more boundaries. I wanted to be the ignorant guy. I didn't want references that I didn't know. It all comes back to my original vision--a tool for readers to discover new books."

Gradually, Heath and Kuebler both withdrew from the editorial aspects of the journal they'd founded. Heath grew more interested in the design aspects of the magazine, Kuebler in reviewing.

As Lorberer puts it, "We all learned what we liked and what we didn't like about that job. I guess I liked enough of it to continue."

Neither of the original editors left over "creative differences," both are quick to add. Heath still creates the magazine's often abstract and gothic covers, and Kuebler remains a regular contributor. Instead, the balance of power gradually shifted from one set of hands to another. In 2000, Heath and Kuebler moved to New York City together, to further careers in editing and publishing. They still work in publishing: The intensity of working on an underfunded start-up for several years hasn't driven them away from the book world. (Though, for what it's worth, they are no longer a couple.)

Having lived through its start-up years and become slightly less underfunded, Rain Taxi has actually grown since the transfer of power. In addition to sponsoring a host of literary events, Lorberer and Everding now ship out some 15,000 copies of each issue, both to subscribers and for free distribution at bookstores in 45 states. Alaska, Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, and West Virginia have yet to be infiltrated.

The phrase "literary community" should probably only be employed when the time comes each year to hoodwink generous foundations and their venerable administrators. Yet it is in developing a public presence for the local literary avant-garde that Rain Taxi has thrived in recent seasons. Josie Rawson has warm memories of Rain Taxi's first reading in 1998, given by the Chinese-born poet Arthur Sze. "He gave a reading that was transfixing," she says. "Here was a man who presented his own material in so compelling a way, all you can do was sit there sort of stunned."

More concretely, however, Rawson remembers what happened afterward, when Sze and his listeners converged upon her home. "There were a bunch of writers hanging out in a way that you'd imagine other writers in another time and another place did. We sat on my back porch, talking about poetry and writing for hours, like it mattered. It's the sort of thing I didn't realize was so rare until it actually happened."

Such an idyllic recollection offers a glimpse into the utopian literary community Rain Taxi imagines. Rain Taxi doesn't just stage readings. It brings writers to town--Victor Hernández Cruz, Claudia Keelan, Franz Wright, Clayton Eshleman--sets them up to speak in galleries, and ushers them into a local body of book people (the literary community, if you will).

Lorberer and Everding had initially found such an environment as graduate students at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, which is where they first met. Then they migrated to Baltimore, where they had a near miss in attempting to open a bookstore. The next stop was Minneapolis. "We threw a dart, basically," says Lorberer. "We'd heard it was a good place to live. But at the time I had no idea there was as substantial a literary community as there actually is."

Oddly enough, a big chunk of that community was composed of people Lorberer and Everding already knew quite well. "There must have been a half dozen people who went to the U Mass grad program who wound up in the Twin Cities," says Bill Waltz. Waltz, who publishes the local poetry zine Conduit was one of those transplants. "There was sort of this mass exodus," he adds with an inadvertent geographical pun.

And key to that collaborative spirit, it would seem, is the muting of individual voices for the sake of the project. "We're trying to give pride of place to the work, and to place personalities second," is how Lorberer describes the reviewing tone he nurtures. "I was talking to the editor of a journal, who should probably remain nameless in light of the story, and they were talking about their Web page. That journal's most accessed page, the guy told me, is the one where they have the pictures of their interns." Rain Taxi has no pictures of its interns online. In fact, it currently has no interns.

And so, it was a surprise to find a page full of negative letters responding to a review by David Foster Wallace in the summer 2001 issue of Rain Taxi. "Elegantly pointless, me-obsessed, academically-challenged, falsely objective, asshole-scratching, hickified piece of writing" is what Robert Bly called Wallace's essay. None of the responses to Wallace's review of The Best of the Prose Poem: An International Journal (White Pines Press) was packed with quite so much hyphenated vitriol as Bly's. The response from anthologist Peter Johnson himself, for instance, was appropriately bemused. Then again, one Morton Marcus declared, "Wallace's review was shameful, not only for him writing it, but for you printing it." Not coincidentally, Marcus is a prose poet himself.

To be fair, the piece in question invited some measure of controversy. Wallace's three-page spread was quite a coup for Lorberer and company, as this top-hole author was paid as much as all the other reviewers (which I will remind you is nothing). In a typical trumping of form, the author of the exquisitely and exhaustingly footnoted Infinite Jest broke down the anthology into numerical components. The result was a rather impassioned piece masquerading as a dry encyclopedic rendering, one you're certainly entitled not to be dazzled by, particularly if you've already consumed your annual quota of DFW metacriticism and minutiae. But it did address the work in question, even if it also went out of its way to tweak the phallic connotations of editor Peter Johnson's name. Unlike most reviews in Rain Taxi, this was a verbal performance, in which the critic assumed as much importance as the text.

Perhaps the vehemence of the response suggests just what an exception this piece was to Rain Taxi's typical fare. The journal does indeed publish negative reviews, but it does so sparingly, and none are outright diatribes. The journal is not argumentative in tone. As Lorberer explains, "The reason that the majority of the reviews are positive is that the process of selection itself is an aspect of reviewing--we're trying to select the best of the best. My hope is that the reviews are substantive, and that they're not just cheering the writer on."

Rawson agrees. "There are so few avenues in the reviewing press for praise for books from small presses, independent presses, it's hardly worth wasting space on books nobody should be reading anyway."

Yet not everyone believes that treating lesser-known works with kid gloves does the literary scene any favors. In a trenchant (and characteristically bombastic) broadside on his Web site www.cosmoetica.com, local gadfly and poet Dan Schneider argues that Rain Taxi's "puff pieces" ultimately add up to nothing more than a "magalog." "These 'supposed' journals," Schneider writes, "have become--in effect--mere book catalogs. They give title, author, publisher, price, a rosy review, and sometimes even ordering/contact information."

Many of the contributors to Rain Taxi are either published or prospective poets or writers of fiction, and this may inform the occasional gingerly handling of others' work. The right of a particular book to exist--or the value in its existence--is rarely questioned. A Rain Taxi review doesn't argue.

A journal reflects the tone of its editor, and like Lorberer himself, these reviews are sure in their presentation of the facts--not smug, but so assured they feel no need to protest. Which raises the question of whether it is possible to have a dialogue when both sides agree. After all, when we imagine Rawson's evocation of "writers in another time and another place," staying awake long into the night, we imagine them arguing. Surely a literary community could be created from vigorous dissent, no?

Don't ask me. I'm not about to risk my livelihood on that assumption. Eric Lorberer, however, relies on his ethos for groceries and the mortgage. And it's a belief he's been laboring to disseminate just about anywhere people discuss contemporary literature. Which is why Lorberer doesn't have to make an argument for his editorial position. Until Lorberer gives up or the money runs out, his vision will continue shipping four times a year.

City Pages Volume 22, Issue 1090 October 24, 2001