by Claude Peck

“Bliss is such a simple thing,” wrote James Schuyler. Also, “the wires in my head / cross: kaboom.” Navigating these opposite shores in a tumultuous life while leaving behind wondrous, one-of-a-kind poems was Schuyler’s mystery and his miracle.

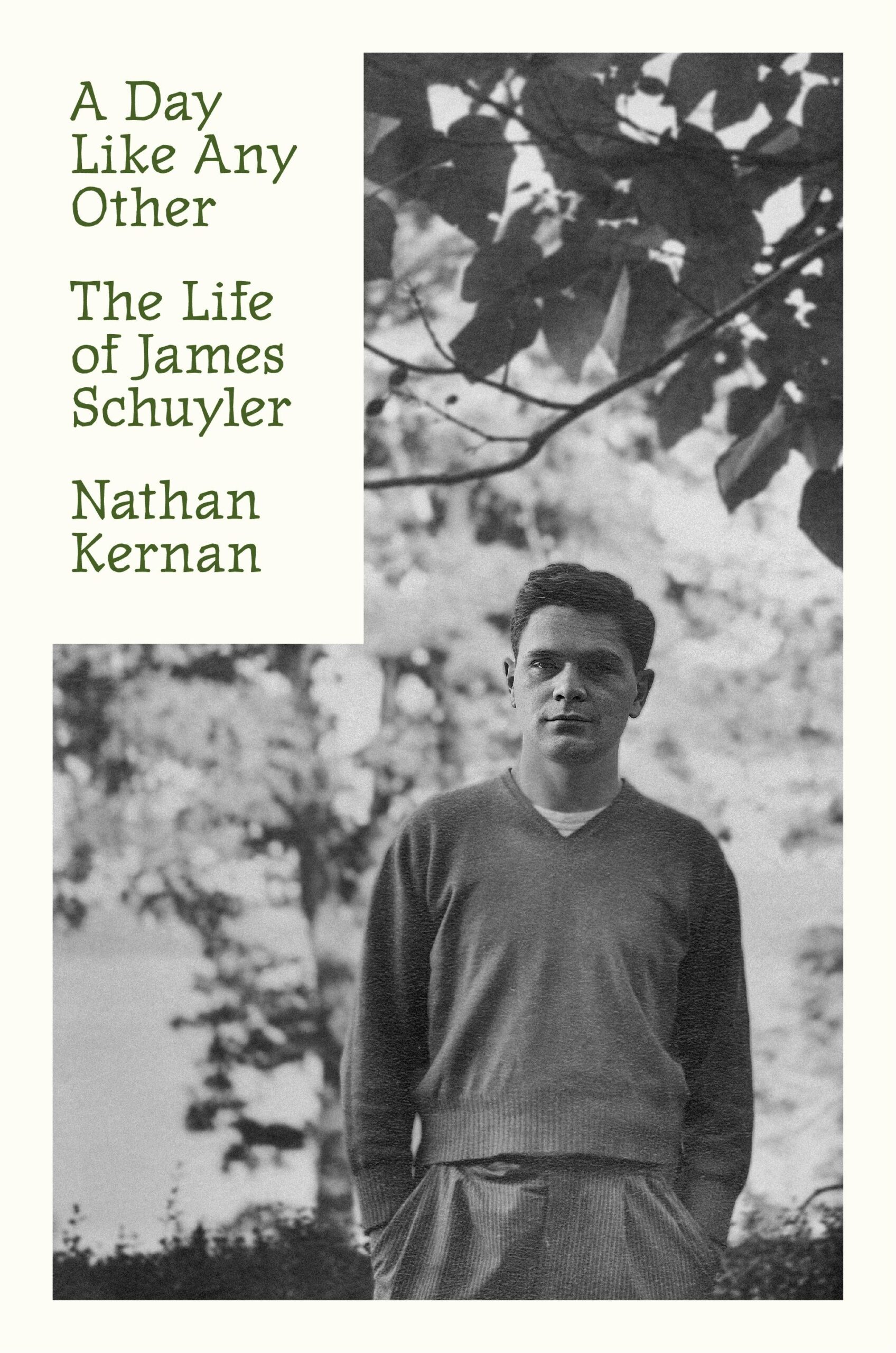

Schuyler, hailed by critic Helen Vendler as “Whitman’s legitimate heir,” was born in 1923 and died in 1991; the decades since have seen publication of his Collected Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995), art writings (good), diary (better), letters (best), and a gem-filled volume of uncollected poems—but no full-length biography until now. Informed by research and interviews dating to the mid-1990s, Nathan Kernan’s A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $35), is packed with detail.

Long may this remarkable “Life” live, and may it lead hordes to discover what David Lehman has called “the best-kept secret in American poetry.”

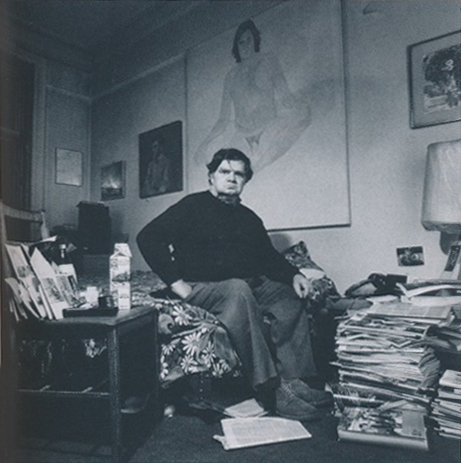

A Room of His Own

In September 1986, when he was sixty-three, Schuyler lived at the Hotel Chelsea, on the sixth floor, with French doors opening onto a skinny iron balcony above busy 23rd Street. Schuyler had agreed to let me audio-record him at home reading some of his love poems for a gay radio program I hosted in Minneapolis. (Only later did I learn of Schuyler’s stage fright, a phobia so severe that he had never given a public reading.)

Schuyler lived in conditions that seemed scandalous for a Pulitzer Prize winner and leading light of the New York School of poetry. His room at the fabled, shabby Chelsea had a tiny galley kitchen, a single bed, a few dusty houseplants, and a portable typewriter; books, typescripts, and vinyl records were strewn about; on the walls were paintings and drawings by such friends as Joe Brainard, Fairfield Porter, Jane Freilicher, Anne Dunn, and Darragh Park.

As he sat in the room’s sole comfy chair, taking sips from a glass of light-brown iced coffee, Schuyler read slowly and clearly, his “esses” sounding a bit like “eshes.” He read eight poems from the “Loving You” section of The Crystal Lithium (Random House, 1972). I asked for a few more. He said no. Then he agreed to read “A Blue Towel” from Hymn to Life (Random House, 1974)—an ode to happiness about a day at the beach with a lover. It ends with “Quiet / ecstasy and sweet content” and wonders “why are not all days like / you?” The “you” is both day and lover, and the rhetorical question, from a man who survived so much chaos and sour misfortune, is supremely touching.

As I was leaving, we hugged and he called me “sweetie.” It surely was not a day like any other. We subsequently traded a couple of letters, but Schuyler and I never met again. In the five years before he died, his stage fright tamed, Schuyler gave nine public readings, starting in 1988 with a legendary SRO appearance at the Dia Foundation in New York City at which, Schuyler later exulted to a friend, “I was a fucking sensation.”

“No Juvenilia”

Aided by candid autobiographical revelations in the poems, Schuyler fans already know the highs and lows of his adult life. His early life is another matter. Schuyler wrote in his Diary in August, 1985, “Anyone who ever wants to write my biography will have his/her work cut out for her/him, since virtually no documentation or juvenilia exist.”

Given our tendency to sift an artist’s youth for the point where the weather shifted and they diverged from mere mortals on their path to greatness, it is gratifying to glean new details unearthed by Kernan about Schuyler’s early years.

He was born to Marcus James Schuyler and Margaret Daisy Connor in Downers Grove, Illinois, in 1923. His father, of Dutch ancestry, grew up on an Iowa farm until leaving home and becoming a printer and later a journalist with social-justice leanings.

Kernan points out that James worked on his high-school newspaper, perhaps emulating his father, and that “the dated, daily nature of newspapers is reflected in the great many Schuyler poems that bear dates and immortalize particular days.”

The poet’s mother, of English and Irish roots, grew up in Albert Lea, Minnesota. Her mother, Schuyler’s “gentle grandma Ella,” was fondly remembered in several later poems. James’s maternal grandfather committed suicide at twenty-nine by drinking morphine.

Margaret had a college degree and worked in Chicago and later in Washington, D.C., in jobs that aligned her with progressives and early feminists. She got into law school at the University of Chicago, though she never enrolled. Academically at least, James fell far from his mother’s tree. Though bookish in his youth (he memorized big chunks of Wallace Stevens), he was a poor student in high school and flunked out of Bethany College in West Virginia after less than two years. The turbulent 1960s and ’70s were his most productive years as a poet, yet this son of lefties rarely mentioned politics, civil rights, Vietnam, Nixon, or gay liberation.

When James was six, his parents divorced. His mother remarried building contractor Berton Ridenour (“an old book burner” and “a big phony,” per his stepson). By 1937, after a few years in D.C., the family had moved to East Aurora, New York, twenty-five miles from Buffalo.

The college dropout enlisted in the Navy during World War II but went AWOL eight months later on a sex-and-booze bender in New York City. His “undesirable discharge” for homosexuality came after he spent three weeks at hard labor at a bleak military brig on Hart Island. Schuyler didn’t say or write much in later years about his abortive Navy career, which Kernan asserts was “not only traumatic, but shameful and embarrassing.”

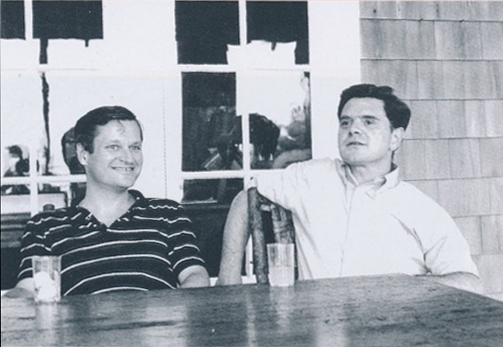

John Ashbery and James Schuyler, Great Spruce Head Island, ca. 1968 (Photographer unknown, James Schuyler Papers, Archive for New Poetry, Mandeville Department of Special Collections, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California)

To New York, Italy

The immediate postwar years found Schuyler in New York, working a dull job at the Voice of America and taking up with Spanish Civil War hero Bill Aalto, a strapping Finn with a violent streak. A modest inheritance from Schuyler’s paternal grandmother financed the couple for two years in Europe, mostly in Italy, where they shared a house in Ischia with W.H. Auden and his partner, Chester Kallman. Schuyler typed poems for Auden. He learned enough Italian to tackle some translations of Giacomo Leopardi, whose poems Schuyler loved. Visitors to Ischia included Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Picasso biographer John Richardson (with whom Schuyler had “intense, rough sex” on a terrace).

Schuyler and Aalto split after nearly five years together, and Schuyler returned to New York in 1949. Writer Anatole Broyard, in his vivid memoir Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir (Crown, 1993), recalls this as a time when rents were cheap and “the streets and bars were full of writers and painters and the kind of young men and women who liked to be around them.”

Crucially to the future of American letters, Schuyler came to know a lot of people in this free-wheeling creative coterie, but two were of special importance: “James Schuyler’s close friendships with John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara, which began in early 1952 and lasted, in O’Hara’s case, for most of the decade, and in Ashbery’s to the end of Schuyler’s life, determined the direction of his life and work.”

Schuyler loved the early works of John and Frank (both Harvard grads); Schuyler wrote that, in turn, they “made me feel that I wasn’t just a poet who was being tested but that I was a poet”—the encouragement was “the most important moment of my life.” The three men—all gay but with varying degrees of openness about it—along with Kenneth Koch and Barbara Guest became known as the New York School of poets.

The “school” was at best a loose alliance, with clear differences among its main writers, but united by friendships, time and place and a shared love of painting, ballet, movies, music, cartoons, collaboration, and a “manner” that was anti-didactic, conversational, miles from the high seriousness of Pound and Eliot, more like “jazz that someone like Prokofiev might write.”

Schuyler’s thrill at meeting Ashbery and O’Hara did not prevent a major setback soon after, when he had a manic episode that led to his first psychiatric hospitalization, a stay that lasted ten weeks. While there he wrote the early short poem, “Salute,” which opens with a statement-question: “Past is past, and if one / remembers what one meant / to do and never did, is / not to have thought to do / enough?”

Kernan argues that A Day Like Any Other is not intended as a critical biography, though the book contains thought-provoking discussions of a handful of key poems (“The Crystal Lithium,” “Dining Out with Doug and Frank”). Of “Salute” Kernan points out the irony of a poem written in a mental hospital with a title that in Italian means “health.” I also can’t help hearing in the line “to do and never did” an echo of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be.”

Schuyler’s 1950s mixed sex, love affairs, and art with prodigious amounts of drinking. He and the charismatic, hyperkinetic O’Hara shared an apartment, jobs at MOMA, and a hectic artistic and social life. Schuyler was gathering the stuff of poems, but not writing many of them.

With his boyfriend, pianist Arthur Gold, Schuyler returned to Europe for several months. He met lifelong friend, Fairfield Porter, as well as other painters, chief among them Grace Hartigan and Freilicher. He wrote the novel Alfred and Guinevere (Harcourt Brace & Co., 1958).

It was an era when poets wrote about painters, and painters painted their poet friends. Collaborations flourished. In 1955, Schuyler began contributing short reviews for Art News magazine. He and Ashbery co-wrote, line by line over many years, the comic novel A Nest of Ninnies (Dutton, 1969).

Instability

In addition to his precarious mental state (variously diagnosed as severe depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) Schuyler was “precariously housed for much of his life,” a fact reflected in many poems, as noted by perceptive British scholar Rona Cran. Yet he is rightly celebrated as a superb poet of place whose poems often begin with the view out his window, whether urban, suburban, rural, or psych ward. In 1959, for one example, Schuyler fled a Hamptons rental after a breakup, couch-surfed in Hoboken and the East Village, then hacksawed his way into the apartment on E. 49th Street that he once shared with O’Hara, which by then was condemned, padlocked, and roach-infested.

Housing-wise, Schuyler was ostensibly better off when, beginning in the early 1960s, he lived outside New York City: in Southampton with Porter, his wife Anne, and their children, and at the Porter family summer home on Great Spruce Head Island in Maine. Along with a Vermont house owned by friend and writer Kenward Elmslie, these bucolic places fueled the poet’s endlessly inventive, original way of writing about flowers and trees, the ocean, weather, and light. Though remembered as his happiest years, they were also fraught, as Fairfield was in love with Schuyler, creating myriad complications.

After the Porters finally asked him to leave in the early 1970s, Schuyler lived in a succession of crummy New York rooms, including one where he started a fire in bed, burning himself so badly that he required skin grafts.

At a New York bathhouse in 1971 Schuyler met and began an intense affair with Robert Jordan, a Brooks Brothers salesman with a wife and kids in New Jersey. Liked by few of James’s friends, “Bob” nonetheless inspired Schuyler’s tender, vulnerable “Loving You” poems.

Despite chronic poverty, well-documented mental breakdowns, and sketchy housing, Schuyler’s writing flourished in the 1970s, with the novel What’s For Dinner? (Black Sparrow Press, 1978) and four of his five poetry volumes published between 1969 and 1980. This output included the masterful long poems that anchored his final four books.

In his last twelve years, thanks to a network of friends, a trusted shrink, a caring physician and a multiyear stay at the Chelsea, Schuyler experienced more stability—seeing old and new friends, eating out, enjoying New York.

Schuyler mostly narrates his poems from a condition of gratitude. Dark-themed poems are notably rare. How was it that a man “so tormented by demons,” as David Lehman put it, “would be, in his best poems, so skillful at conveying what happiness feels like?”

Kernan’s essential, readable, sensitive biography offers keen fresh insights but doesn’t fully answer this seeming anomaly. For that, we can with robust pleasure return to the poems, as in “Afterward,” where Schuyler gives a disarmingly simple account of the end of two recent hospitalizations:

It’s

funny to be free again: to

look out and see

the gorgeous October day

and know that I

can stroll right out into

it and for as long as

I wish and that’s what I

do. This room needs flowers.

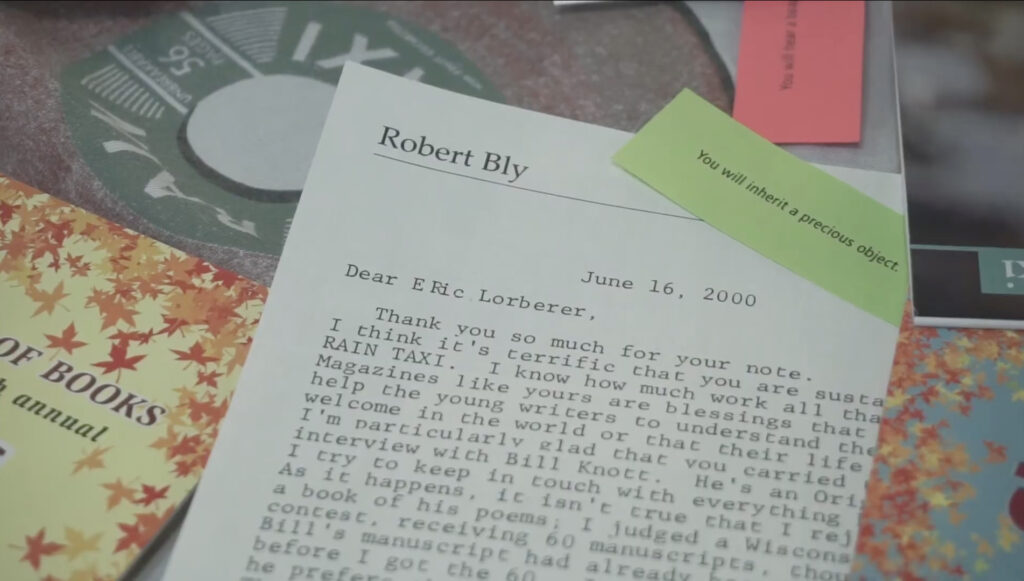

Editor’s Note: The following poems, read by James Schuyler in his room at the Hotel Chelsea, were recorded by Claude Peck on 9/20/1986. They are copyright Claude Peck and used by permission.

“Letter to a Friend: Who is Nancy Daum” from The Crystal Lithium (1972)

“A Blue Towel” from Hymn to Life (1974)

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025