by Allan Vorda

Álvaro Enrigue was born in Guadalajara, but at an early age, his family moved to Mexico City. His father was a lawyer; his mother, a chemist who was a war refugee from Barcelona. He received a degree in journalism from Universidad Iberoamericano and became editor of various magazines, including Vuelta, which was founded by Octavio Paz. In 1996, when he was twenty-seven, he was awarded the Joaquin Mortiz Prize for his first novel, La muerte de un instalador (Death of an Installation Artist); since then, he has published six novels, three books of short stories, and a volume of essays. Books that have been translated into English include Perpendicular Lives (Dalkey Archive Press, 2008), Hypothermia (Deep Vellum, 2013), and Sudden Death (Riverhead, 2016)—the latter a hilarious tale of a tennis match between the Italian artist Caravaggio and the Spanish poet Francisco de Quevedo.

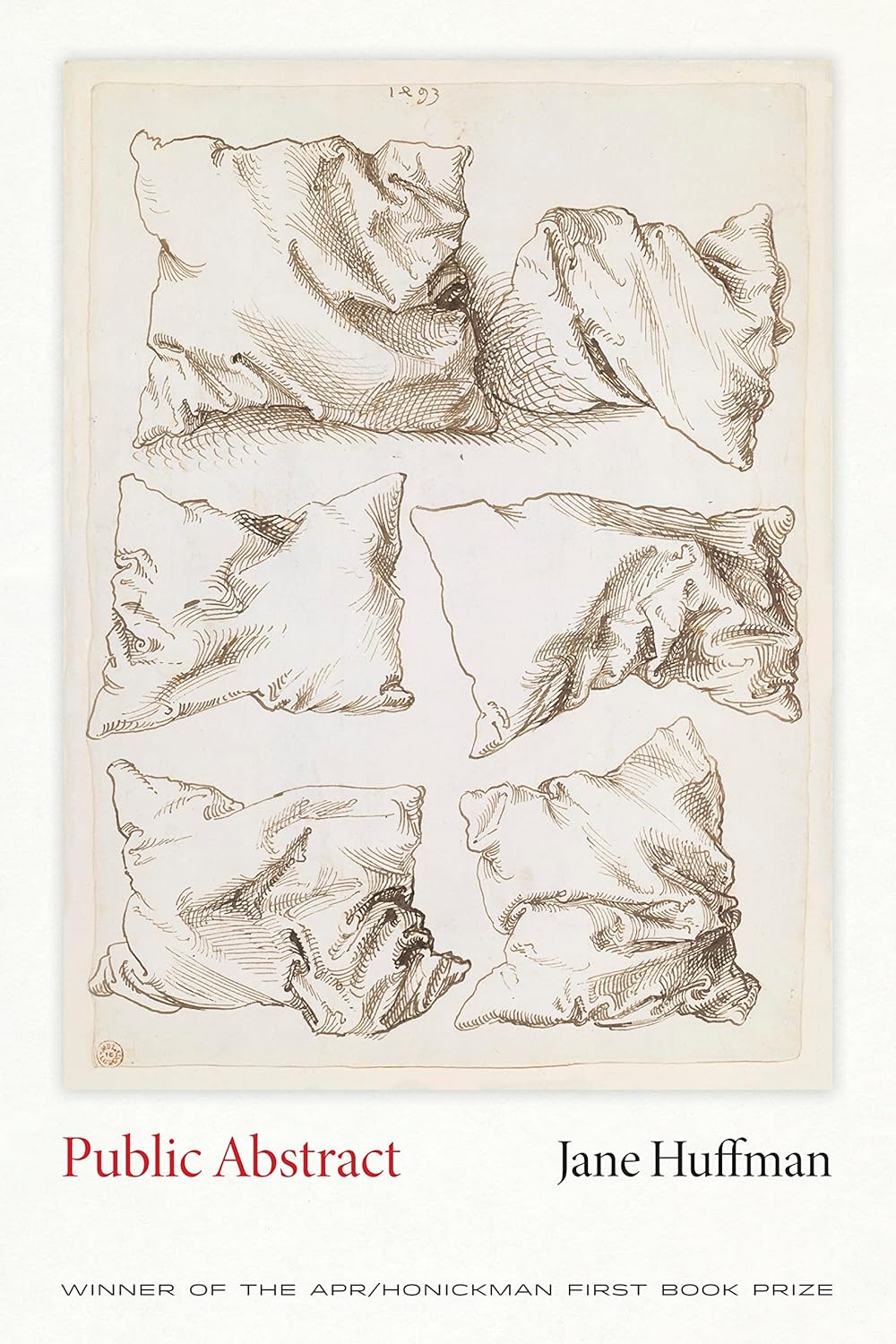

Pursuing his penchant for writing about the historical past in the most imaginative of ways, Enrigue’s latest novel is You Dreamed of Empires (Riverhead, $28); deftly translated by Natasha Wimmer, the book sets the 1519 meeting of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés with the Aztec emperor Moctezuma in a captivating dreamscape. We discuss this new book and much more in the interview below.

Allan Vorda: What was it like growing up in Guadalajara, and how has it and Mexico changed since then?

Álvaro Enrigue: I was born in Guadalajara, but I never lived there. When my mother’s pregnancy was arriving to term, my father, who worked as a lawyer for the local government, got a position in the Ministry of Finances of the Federal Government in Mexico City. As soon as I was born, the family moved to the capital. I am the fourth of four children, and Jorge and Maísa had been jumping from city to city in search of better opportunities since they got married, moving each time with a new kid in the car—a pale blue Rambler that kept working until the 1980s. When I was added to that car, they were masters of moving with kids, so I just lived in Guadalajara for the very few days it took them to register me.

That legendary move to Mexico City with four crazy kids was the last one. They never left and they still live there, in a little house in Coyoacán, two blocks away from the Blue House of the Kahlo family and three from Trotsky’s final address. It was a peculiar moment that left a strong mark on me. The ’70s were the apex of the National Revolutionary Party’s rule, its moment of maximum stability. A country that had been mainly rural and commodity-dependent was entering the spiral of industrialization that has made it the productive powerhouse it is now. The enormity of the oil reserves produced a strong middle class in which I grew up, bored as hell: Mexico City was already enormous, but it was also quiet, provincial, and ugly. No rock and roll for Mexico City kids—it was considered a nefarious imperial occupation strategy. Things changed, and from one night to the next morning, on January 1994, when NAFTA was implemented.

AV: What was your education like, and did your journalism experience help you as a writer of fiction and essays?

ÁE: Both of my parents were from small towns of opposite coasts. Maísa is a war refugee who arrived when she was a girl—my grandfather had escaped a few years before from a French concentration camp and arrived in Mexico thanks to the boats of President Cárdenas, whose memory we will always honor. Maísa grew up on the Gulf Coast, in a small city, back then not very different from Macondo. My father is from a small town perched in the sierras that end in the Pacific Coast. It’s named Autlán and may ring a bell for you because it is where Carlos Santana was born. They loved Mexico City—they both had gone to college there—but I think that they were also, and are still, always a bit terrified of it. It’s a city with the size and the population of a republic, after all. They sent us to Catholic schools that had connections with their hometowns.

I was very unhappy in Catholic school—discipline was brutal and the curriculum absurdly demanding for a kid that cared only for baseball and comic books—but as time passed, I ended up getting some benefits from it. Myself, as my brothers and sister, developed a strong work discipline that has kept us afloat economically. And when I arrived at college, I was already familiar with the great books of the humanist tradition, and rereading is always easier and more enriching than reading for the first time. I knew how to use a library and understood that if you don’t write well, you don’t think well. I think that we survived all right because before the first day of school, every year, my father would put us together in the living room and repeat an admonition: “Never, ever, ever, put yourselves in the situation of being alone in a room with a priest.” My father is Catholic, but he is also a realist.

Catholic school also gave another lifelong gift: I developed a love for soccer that has brought me great joy. We were coastal transplants, a baseball family, but the only thing that really mattered in Catholic school in Mexico City was soccer. For the kids, the teachers, and the priests, all was secondary to the coronation of our teams in the local tournaments. I find it the most welcoming of all sports.

Journalism was never as important to me. I never cared that much for immediate reality, but journalism landed me with decent jobs when I finished college. I’m thankful about it, but by then I already knew that I wanted to be a writer and a professor.

AV: Your first novel, La Muerte de un Instalador (Death of an Installation Artist) won the prestigious Joaquin Mortiz Prize for fiction. Will this novel and your other works currently available only in Spanish ever be translated to English?

ÁE: I don’t know, and I don’t care that much. I’m not sure I would like my old books if I read them. Of course, publishing stuff is always exciting, and the little money I make with the novels is always welcome—now it’s me who has four children. The publishing part of my work is done by incredibly generous and smart people. They know their trade and, if someone asks, I will have to sit down and read the work again before saying yes or no.

AV: What does a typical day of writing entail for you?

ÁE: I write in the mornings—first by hand in specific notebooks, always using the same kind of pens. Every day I use a different ink color because, once I begin to pass that first very messy original to the computer, the different colors feel like a compass. And it gives me a sensation of moving forward: a bunch of pages, a bunch of days. In the early stages of a book, I just write for a few hours a day: in a café, in a library, in a park, but never at home. Most of my last three novels and the essay book I’m working on now have been written between the New York Public Library and the legendary Hungarian Pastry Shop on Amsterdam Ave. I tend to be the stay-at-home parent even when I go twice a week to the university, so my professional days are short and my afternoons with the children are splendid. When I move on to the word processor, I can keep working for an undefined number of hours—the real literary writing happens for me in that stage. But again, it is never eight or ten hours; there are children, errands, cooking; splendid afternoons.

AV: How does the reception of your writing differ between Spanish speaking countries and the U.S.?

ÁE: Reception is a mystery for me. There is the fuss about a book when it comes out, which in the U.S. tends to be enormous because the relations between the publishing industry and the media interested in literature are more intense than in any other place. That’s always impressive for me: I am still the boy from Coyoacán, and it was not in my horoscope that I would be sitting down signing books in a bookstore in San Francisco or Edinburgh, or that a New York Times critic would pay any attention to my work. Then again, twice a year, there are the usually depressing sales reports—except in Germany, which is another mystery. I never sell enough books to pay for the timid advances I get for my manuscripts. Critics in all languages tend to be very generous with my work—something I am not. I feel like an impostor, but I suppose everybody does.

Also: who reads and why? If I knew, I would be a millionaire. And what I find truly moving about my job is the opposite of fame. Once in Jaipur, India, I was having a tea and a cigarette on a beautiful terrace in the fantastic Jaipur Book Festival. I had just gone through the usual and very humiliating experience of not signing many books while next to my table were some literary superstars with enormous lines of people. A young man from Kerala came to the terrace with a pile of my books—in Spanish!—to be signed. He had made an enormous trip from South India so he could have those volumes dedicated. That morning justifies me as a writer: No matter what goes well or wrong in my career, I reached that person.

AV: Hernán Cortés, Moctezuma, and Cuauhtemoc are some of the characters who populate Sudden Death. Were you already thinking then about using them as major characters for You Dreamed of Empires?

ÁE: No, I was not even thinking about using them in Sudden Death when they jumped into that book. I discovered late in the writing process of the novel that the patron of Francisco de Quevedo was married to one of Hernan Cortés’s grandchildren. As I was working with a fellowship of the Cullman Center at the New York Public Library, I could ask for any book I wanted and it would materialize on my desk the next day. I ended up engulfed in the story of the heirs of Cortés and they naturally moved into the story; they were the Mexican connection that the novel was missing.

AV: What research did you do to write You Dreamed of Empires?

ÁE: The number of books I have read about Tenochtitlan and its fall is somewhere between ridiculous and oppressive. It’s a lifelong obsession. My parents, small-town folks living in the big city, took us out of town every weekend to have some fresh air. If you live in Mexico City, some of the day trips you can take include visits to archeological sites—there are hundreds of antique complexes you can see without ever repeating.

In 1979, it was discovered that the old citadel of the Temples of Tenochtitlan was still there, and it was excavated and open to the public. I went for the first time with my school, and it just blew my mind. We were the Rome of the Americas, and we were not even aware of it! From then, I have spent my whole life reading about it, never thinking that I would ever have a use for all that knowledge. Little did I know I’d be writing a small critical book about literary production in the years of the transition between Tenochtitlan and Mexico City. I also teach a class about it.

AV: What is your opinion of Moctezuma and Cortés as leaders in real life?

ÁE: Cortés was smarter and more sophisticated than in the novel. And crueler, if you can believe it—he was an infamous, evil man. He was also a very short guy. I took out all the references to his stature in the book because it is not my job to body-shame anyone.

We don’t know much of Moctezuma, except for his physical appearance, described by various Spanish soldiers: strong, tall, with a straight nose and, strangely, curly hair. He was in an enormous crisis in 1519. After expanding the empire for a decade as the most successful tlatoani of Tenochtitlan ever, he made one bad decision after another, including not killing the invaders immediately, which alienated his allies. When Cortés arrived, he knew that the Triple Alliance that controlled the empire from central Mexico was crumbling and used that information to his advantage.

AV: Did Moctezuma in real life consume magic mushrooms like he does in your novel? If so, did this contribute to his becoming an ineffectual leader?

ÁE: Yes and no. Yes, because the religious practices in Mesoamerica involved the consumption of hallucinogenic substances, and before being emperor, Moctezuma was the supreme priest of Tezcatlipoca. But the relationship to drugs of the indigenous people of central Mexico is completely different than ours. It’s heavily ritualized and responds to specific disciplines. It’s not something you do for recreation, or to tolerate the difficulties of life, but to access a different stage in your relationship with the material world.

AV: You depict Moctezuma marrying his sister Atotoztli—did this happen in reality? When Moctezuma was captured it was said he had one hundred children and that fifty of his wives and concubines were pregnant. What do you know about Moctezuma’s wives and children?

ÁE: Atotoztli and Jazmín Caldera, whom I see as the main characters of the novel, are completely fictitious. Moctezuma had many concubines, and they all were princesses from the other altepeme—altepetl in the plural—the equivalent of a nationality in old Mexico, something between a republic and a city-state. He had a first wife who ruled next to him, survived him, became an important entrepreneur and political figure in New Spain, and whose children were the royal family.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan all the children were taken to Spain and their descendants became part of the Spanish nobility. Some of Moctezuma’s progeny returned to Mexico where they continue to be a prominent family. For example, the current Mexican Ambassador to the U.S. is a Moctezuma, as is the most important living archeologist of Mexico, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma. When I was a teenager, I was in love with one Moctezuma girl, but she didn’t have any interest in me. There is a legend I like about a Mexican empress who ruled alone just before Moctezuma’s father was named emperor. The legend says that she was named Atototztli. I took her name because I love how it sounds.

AV: You also describe how Caldera puts on a breechcloth—how did you research this topic?

ÁE: A big part of the novel was written during the pandemic, so we had left New York and were living in a tiny house that the Argentinian poet Lilia Zamborain lent to us on Shelter Island. On one of those really slow rainy mornings of the Long Island summer, I found a set of instructions to wear a breechcloth on a fashion site online. Bored as I was, I practiced with the bedsheets. I was very unsuccessful. It was impossible to keep it on for more than a few minutes, but it was not a total loss of time. My appearance was so hilarious that I provided my wife with tons of ammunition to laugh about me for days. It was a period when having something to laugh about was priceless.

AV: When Caldera shaves and cuts his hair, has he already made up his mind to stay in Tenochtitlan. By changing his appearance to assimilate, does he become a different person with a different identity?

ÁE: That’s for the reader to decide, but he sure tries. Caldera is a one hundred per cent imaginary character, but that doesn’t mean that he is an impossible character in the period. Cultural adaptability and open sexualities were more common in the 16th century than in the 19th or early 20th centuries. Many forms of kinship, extinct today, demanded a fluidity unthinkable in modern life: Only very rich and noble people had private beds, most jobs demanded the separation of families for long periods, and the known world was expanding like crazy. Thus, adaptation to change was an essential tool for survival. The historical Gerónimo de Aguilar, Cortés’s translator to Mayan, decided to go European again, as did Álvar Cabeza de Vaca, both after a long period living as Indigenous Americans, but many others never returned and even fought against the occupation of the continent. Gonzalo Guerrero, who was a friend of Aguilar, stayed with his Maya wife and children and died defending his adoptive land dressed up as a Maya warrior.

AV: Your work is highly metafictional; you begin one chapter, “If Jazmín Caldera had existed, if he had crossed the threshold into the throne room of Axayacatl’s Old Houses at almost five in the afternoon on November 8, 1519, he would have seen before him . . .” What went into your decision to inform the reader Caldera is a fictional character in what some might call a historical novel, and what was your main reason for creating him?

ÁE: I don’t think that I write historical fiction at all. In this novel I worked with historical archives to generate literary fiction in the tradition of Latin American literature of the fantastic: Juan Rulfo, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Juan José Arreola, just to name the best of them. And I don’t believe in the need to suspend credibility to read or write fiction—I think that is a 19th-century superstition. Caldera’s function in the novel is to provide a more modern point of view for contrast. He understands that the cost of the imperial expansion of Spain was too high: the original population of the Americas was reduced to ten percent during the first 100 years of occupation. It’s the worst war crime ever, after the annihilation of the Neanderthals, I suppose.

AV: You write: “Jazmín Caldera, who has to be a learned conquistador—like Hernán Cortés or, to a lesser extent, the surgeon Bernal Díaz—for this novel to work, would have admired the geometric design of the citadel.” This authorial intrusion is very interesting. Can you comment on why you used this technique?

ÁE: Contemporary architects leave a register of how buildings were originally when they remodel them. I think that writers can leave registers of how they wrote in the final version of their works.

AV: The paragraph begun with the sentence in the previous question continues as follows:

He would have seen it not as a proliferation of towers, which was how his European contemporaries saw it, but as an emblem or a contemplative vision—which is what it was. From the weighty base to the temples built on top, the structures were architectural variations on descent and ascent; on the passage from the earthly to the aerial. They were like stairways, up which mass was shed on the way to the plane of the gods. Only priests and their sacrificial victims went up these stairs, and to ascend the temple was to lose all earthliness until abandoning oneself in the paroxysm of death. When bodies rolled down the steps it was without their hearts, deadweight.

Juxtaposing beauty and death, this beautiful paragraph serves not only as an example of the quality of your writing, but as a metaphor for the Aztec empire. Why were the Aztecs so brilliant in so many ways (architecture, astrology, etc.), but also immersed in consumptive sacrificial bloodshed?

ÁE: Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, who directed the excavations of the Main Temple of Tenochtitlan in Mexico City, wrote a beautiful essay about that subject titled Muerte a filo de obsidiana—sadly, it has not been entirely translated into English. As gory as it feels to us, human sacrifice made sense for many cultures—not only in the Americas. The Mexica truly believed that dying on the sacrificial stone was a way of giving life to the world. It was a desirable form of death because it produced the best possible afterlife, and the moment of death itself was softened by ritual and the consumption of hallucinogenics. To die on the battleground in England or Spain was much more horrid, painful, and stupid.

Human sacrifice was a system meant to contend with the anarchy and miseries of war. Battles occurred only in the periods of the year in which the fields didn’t need to be attended and in places where the civil population would not be hurt. There were lunch breaks and resting time during the battles, and the idea was to capture other warriors for sacrifice, not to exterminate the whole population of the enemy city. The spectacle of a sacrifice was horrid for sure, but it limited the casualties of war to the professionals; no matter how many skulls they end up finding in the Huei Tzompantli of Tenochtitlan—the temple in which the heads of the sacrificed were displayed—they will always be fewer than the ones dispersed on the battlefield after any European mid-size conflict.

AV: Just as you contrast Caldera’s perceptions with “how his European contemporaries saw it,” it seems your writing has an anti-European slant. Does this reflect strong feelings among contemporary Mexicans?

ÁE: The occupation of the Americas is still a big issue in Mexico that generates enormous polemics. And what I stated in Sudden Death is real: No one ever visits the tomb of Hernán Cortés in the Iglesia de Jesús in Mexico City—not even by mistake. There are no statues of him or streets with his name. I find that much more reasonable—and less sad—than the way in which Americans have embraced their invaders with no questions, as if to be a second-class European was a desirable destiny. That is disturbingly disrespectful of the wonderful, enormous, rich, and deliriously diverse rock that is our continent.

AV: Spanish conquistadores destroyed the tzompantli (skull racks) five hundred years ago, which is estimated to have been home to forty thousand skulls. You describe the tzompantli as a “formal reflection on the foundations of any system of religious thought: We don’t last.” What a remarkably cogent proposition—can you elaborate?

ÁE: Not really: We don’t last and that’s the problem. It’s an essential flaw in our design.

AV: In 2015, archaeologists uncovered a new section of the Tower of Human Skulls; it now has over six hundred. What can you tell us about the tzompantli? Have you seen it?

ÁE: I saw it. Raul Barrera, the chief archeologist of Mexico City, took me there in what could be the best day of my life. I had been trying to reach him for a long time without success and in the end I sent him, hopelessly, the manuscript I was finishing correcting. He answered on August 11, 2021—the date is unforgettable because it was two days ahead of the 500th anniversary of the Fall of Tenochtitlan. He said: “I read your novel; you have some of the buildings placed wrongly. The politicians are not letting us work with the damned commemoration of the five centuries. Why don’t you come to Tenochtitlan tomorrow?” It was as if he had a pass for a time travel train.

And he does. Under all those beautiful baroque palaces of downtown Mexico City, there is now a system of iron pillars, and they are slowly bringing out the city of Moctezuma in the underground: the buildings, the streets, the temples. It’s so impressive. I think that some of the underground halls are open for visitors now.

Barrera’s main contribution to Mexica Archeology is the discovery of the tzompantli, which they will be excavating for a long time. When we got there, we were standing on the balcony from which the tourists would see it. He got excited talking about it and said: “That’s what we will let the people see, but come with me,” and we jumped into an actual street of Tenochtitlan. “Take off your shoes,” he said, “and follow me.” I walked through a street of Tenochtitlan, one that may have supported the golden sandals of Moctezuma, and I got to stand in front of the columns of skulls that you can see only in pictures. Of course, I had to rewrite many chunks of the novel; again, we don’t last.

AV: Switching gears, you convey a fable of sorts about the ant when Tlilpotonqui (the mayor of Tenochtitlan) is talking to Cuauhtemoc (the general) and Atotoxtli (the sister-wife-princess of Moctezuma) about who made a call to arms without his knowing about it; you write : “The general and the princess shrugged, but their manner somehow suggested it wasn’t a display of ignorance, but a plea for him to understand something unsaid.” Is the ant a metaphor for something unsaid?

ÁE: The story of the ant characterizes Tlilpotonqui as a person who doesn’t give a shit about the mythology taught at school. We tend to think about people from the past as fanatic believers in silly stories. It’s one of the many ways of infantilizing Indigenous American civilizations: They believed in weird gods, so they were providentially defeated by Europeans who believed in the One True God. But of course, mythology is a literary form, a series of narrations whose function is to give a common background to a society: I can read and reread with enormous pleasure the Gospels or the Book of Job and understand their social importance and wisdom without believing in their divine origin. Tlilpotonqui, however, doesn’t even remember the story of the ant; for him it is just a children’s story. By the end of the book, Moctezuma (the better strategist, no matter how distracted, depressed, or high he is) teaches him an important lesson: it doesn’t matter if the ant story is real or not, what matters is that its power as a metaphor is enormous.

AV: Your depiction of the Nahua translator Malinalli is riveting. Cortés makes Malinalli live with him as his concubine so he can have her at the ready to translate, yet while she can understand what the conquistadors are saying, she translates only what is in her best interest. A fascinating and tough woman, she is even able to keep her dislike of the uncouth Cortés to herself. Can you elaborate on her as both a fictional and historical figure? I have read elsewhere that some Mexicans consider her a traitor.

ÁE: The interpretation of the figure of Malinalli as a traitor has lost a lot of gas in the last forty or fifty years, thanks primarily to female historians—some working in Mexico, others in universities elsewhere. When Malinalli was forcibly united to the party of Hernán Cortés, there was not such a thing as them and us. There was not even a word for “Indigenous people”; they were all in the Cem-Anahuac—the continent, the world—and that was it. It was the Europeans who began to see themselves as different than the people of the Americas, and that happened decades later. The Nahuatl word for local people, which means “us from here,” didn’t appear until the end of the 16th century.

And Malinalli, of course, could not know that these strange pink guys with guns and horses would eventually produce the worst genocide in history; they were just a small band of eccentrics in the enormous tapestry of a very populated world. She was a destitute princess who saw a chance to regain her power, and she did, not knowing the cost the people of the Americas would pay for it.

It’s important to state that I am not saying anything new. I worked with the ideas and research of many others to try to recreate this enigmatic character that has been fascinating and elusive to me for years.

AV: A hallmark of your literary style is that you frequently have multiple characters digressing in alternating paragraphs. Are there difficulties in trying to write like this?

ÁE: You have no idea how much I work to produce simultaneity in my books without using the word “meanwhile.” I don’t use it because the reality doesn’t work that way. There are no meanwhiles in life; there is only this simultaneous action that we try to capture with language. It’s like quotation marks, which I see as a lazy solution that ruins the sensation of fluidity that conversations have. They are painfully artificial.

AV: In your telling, Moctezuma could have killed Cortés and his men, but he wanted to learn more about the animals he calls “deer without antlers”—horses. If this is true, why didn’t Moctezuma attack when he could have?

ÁE: It’s the idea that sustains the novel, but I don’t know. The nations from the Americas that adopted the horse survived well into the 19th century. In You Dream of Empires, the historical mystery of why Moctezuma let the Spaniards get all the way to the city—and form associations with groups that resented the rule of Tenochtitlan—is addressed by the fact that he sees the military potential of horses (which admittedly makes it even less of a good idea to let them into the city). But that thing of the “deer without antlers,” which Moctezuma says with irony in the novel, is a lie designed to portray the people of the Americas as children. When the Spaniards arrived at what is today Veracruz, horses had been already killed and their dead bodies studied by Mayas and Totonacs, so the Mexica knew perfectly well that they were a different animal. The Nahua word “cahuayo,” which comes from the Spanish “caballo,” was used all the way up to the Spanish-Mexican war; it was the Spaniards who later spoke about the antlers thing, never the indigenous people.

AV: Horses were later critical for Cortés in the Battle of Otumba. This is a battle most U.S. citizens do not know about, but didn’t it change the course of Mexican history?

ÁE: It changed the course of world history. It changed even the weather; so many people were killed or died of the plague in the Americas after the battle of Otumba that the planet became considerably colder.

You know the story, but I will retell it for your readers. After an eight-month stay in Mexico City in which no one really knows what happened, the Castilians are defeated, humiliated, and expelled from Tenochtitlan. They are not chased because the new emperor must be crowned. Cortés wanders in the fields at the northeast of Mexico City, near Teotihuacan, and sends messengers to the Tlaxcaltecas asking for the restoration of their past alliance. While he is waiting for an answer, an army that is small but more than enough to terminate his adventure finds him outside the town of Otumba. The Mexica troops are led by the cihuacóatl of Tenochtitlan—the mayor, more or less—because the new emperor was not feeling well. As Cortés and his troops had been living in Mexico City, they knew the mayor. When they see him on top of a hill directing the combat, they run to chase him with horses and kill him. The Mexica leave the field to reorganize, and they send a messenger to the capital with the bad news of the killing of the cihuacóatl. The messenger returns with even worse news—the emperor has died from smallpox. The empire is headless: It is without both the tlatoani and his second in command. The warriors disband and the Castilians can now make it to Tlaxcala. There is a chance to take the previously undefeated Tenochtitlan—and they take it.

The fall of the capital of the Mexica implies the beginning of colonization as we know it, but it also implies the beginning of a massive movement of bodies from one continent to the other. African slaves worked for longer hours than indigenous ones; they didn’t have a territory to defend once they were transplanted, so revolts were less frequent; and, just like the Europeans, they were able to resist smallpox.

And the Fall of Tenochtitlan finally opens for Europe a fast and safe way to Asia through the China Galleon, which connects Acapulco and Manila. The world finally becomes round, and the economy, global.

AV: What has to be the most mind-blowing aspect of the novel occurs when Moctezuma is high on mushrooms as he enters the temple of Huitzilopochtli, where human sacrifices occur:

I love this room, said Moctezuma, you can’t imagine how I miss being a priest. Where there were splotches of blood, he saw sprays of flowers. The withered fingers of the hands of the great warriors sacrificed during the year’s festivals swayed pleasingly like the branches of a small tree to the beat of some music he couldn’t place, though in a possible future we would have recognized it. It was T. Rex’s “Monolith.”

The priest was also up to his ears in whatever he had taken to carry out his temple duties, so he bent his magic powers of hearing to the music and caught the sexy crooning of Marc Bolan. He smiled. That’s good stuff, he said. Moctezuma swung his hips to the beat. It’s nothing I’ve ever heard before, he replied, but I like it.

And then we get this freaky description where the priest “carefully lifted the clay basin in which the blood of doves sacrificed that afternoon had yet to coagulate—their decapitated bodies sensually dancing to ‘Monolith.’”

To transition like this from 1519 to 1971 is almost like having the reader on mushrooms—it’s totally unexpected. Why and how did you create this amazing passage?

ÁE: I love how you describe it. The novel has the structure of a Greek comedy, with unity of time, place, and action, four acts, and everything. But it should also feel like an afternoon mushroom trip—the real time you take reading the novel is more or less the same time in which the story develops.

I was very careful in trying to reproduce the way reality gets amplified when a natural, gentle hallucinogenic hits your brain. It’s the same world of everyday, but there are little disruptions, curious and intense, that eventually produce a world that looks wider but nevertheless sustains to the logic of life.

About the intrusion of Marc Bolan in the novel, I don’t know—the writing process is way coarser than I would like to accept. I was writing the visit to the temple and, to take a rest—I suffer from back pains that define everything in my life—I played the A side of T-Rex’s Electric Warrior. It’s something I do: listen to a few songs walking around to make sure I don’t stay in the same posture for too long. When “Monolith” began, it was obvious to me that there were connections between the invincible glam of Marc Bolan and the figure of Moctezuma: the feathers, the exposed shaved chest, the wavy hair. And the song is named “Monolith,” which echoes the “Sun Monolith” (the most famous Mexica piece of art) and the monolith that brings war to the world in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It felt fun so I just dropped the song in the scene, and it worked all right.

AV: It seems another song that would fit into this passage would be Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer,” which was banned in Spain. The song is so slow that it would fit seamlessly with a stoned-out Moctezuma, plus Young’s lyric “I still can’t remember when / Or how I lost my way” would seem to fit the mental state of Moctezuma as you depict him for most of the novel, at least until the end, as one who has lost contact with reality.

ÁE: Novels belong to their readers and not their authors, but I would dispute the idea of Moctezuma losing contact with reality in the novel. It may look like that as you see him getting higher and higher as the story progresses, but at the end you see that he always knew exactly what was going on, that he was high because he was reaching out to his gods in order to have their complicity to do what he had to do—as I wish he had done in reality.

AV: This colludes with yet another mind-blowing passage later in the same paragraph: “It took Moctezuma a while to bring it into focus because it came from very far away. When it was finally sharp and clear, it made no sense to him: It was me writing this novel in a yard on Shelter Island. Uh, he said, strange, and he was seized by laughter.” This mixing of fiction and reality via authorial intrusion is a technique that postmodern writers such as John Fowles have used to great effect. What are your thoughts about authorial intrusion?

ÁE: Well, it’s a tradition older than that, as old as novels themselves: The first character you see in Don Quixote is not don Quixote, but Cervantes finishing Don Quixote at his desk. Now, the reference is more focused in You Dream of Empires; it’s a timid tribute to Jorge Luis Borges that is there to make clear that the novel is not historical, but fantastic. When the main character of “The Aleph,” who is named Borges, finally gets to see the miraculous spot that contains everything in a simultaneous way, he sees the whole world and its whole history, including himself looking at the aleph and the reader who is reading about him looking at it. A lovely meditation: All literature is in everything we write, good or bad.

AV: The novel has a surprising end with a revisionist twist, one that makes me wonder what would have happened if Cortés had lost the Battle of Otumba and there hadn’t been a New Spain. Can you envision how different Mexico would be today if Cortés had not conquered Mexico? And what are the positive and negative aspects of the Spanish conquest of Mexico?

ÁE: The Americas were not prepared for the invasion, and the plague was already there when the battle of Otumba happened. King Carlos would soon see the treasure that Hernán Cortés had already shipped to Europe, so a second, or third, or fifth wave of Spaniards would have eventually taken over Tenochtitlan. By the end of the 16th century there were more Africans than indigenous people in Mexico City because of the devastation left by smallpox.

In history, the worst ones tend to win, no matter what national foundational myths are later invented. Just look around and see what the British and their descendants did to this beautiful country—it’s an environmental, political, and aesthetic catastrophe. We have our pathetic middle-class goodies, but we live in a horrendous, unbearably unequal world. And the same can be said about all of Latin America and the Caribbean.

But, if things had been different, maybe the wondrous floating city of Tenochtitlan would have stayed as it was, because the Mexica, weakened by years of suffering the plague of smallpox, would have not been able to resist as long as they did—until the last warrior was killed and the last building destroyed. Just remember what Bernal Díaz del Castillo said about the first time they saw it from the highlands. The lake, the cities around it, with their fortifications and temples full of color, and, in the center, Tenochtitlan floating, an intensely green, self-sustainable city, so vast and so delirious that they could not compare it with towns they had seen, but only with ones they had read about in chivalric romances like Amadis de Gaula.

AV: Thank you for answering these questions. Your writing is magical.

ÁE: And your questions brilliant. Thank you.