by John Wisniewski and Eric Lorberer

One of the exciting things about contemporary literature is how writing, translation, and criticism exist on a continuum, each practice bolstering the others to take the art to new heights. Occasionally, this continuum manifests in a single individual, a polymath of seemingly boundless energy. In the following interview, readers will discover one such individual, Peter Valente; his many publications and activities of the past decade are better described by him below than in any introduction we could write. With each of us curious about different aspects of Valente’s prodigious output, we had many questions, so we thank him for expansively addressing them all.

Rain Taxi: Tell us a bit about your literary background—how did you come to the world of writing?

Peter Valente: I first published poems in those xeroxed, hand-stapled mags that were still coming out in the early ’90s, such as Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy’s wonderful Mirage #4 [Periodical]—they published my first poem in 1994. Later, I published work in literary magazines like Lee Chapman’s First Intensity and Peter O’Leary’s LVNG. I had graduated from Stevens Institute of Technology with a degree in Electrical Engineering and a minor in American Literature in 1992, and I was living in Cliffside Park, New Jersey, working in a bookstore. I attended as many readings as I could at the Poetry Project and elsewhere in New York City—a great way to get a substantial education in poetry.

I also read everything I could get my hands on from the great small press publishers of the day—Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop’s Burning Deck, Lyn Hejinian’s Tuumba Press, Steve Clay’s Granary Books, Annabel Lee’s Vehicle Editions, Geoff Young’s The Figures, and many others. I used Spencer Selby’s list of experimental magazines to find places to send work, and when I sent some pages of artwork to John M. Bennett at Lost & Found Times, he wrote on them and sent me back photocopies to give out for free. These early experiences with publishers taught me so much about community and the possibilities for collaboration, which came full circle for me later when I collaborated on a book with Kevin Killian called Ekstasis (BlazeVox, 2017). Oh, and during this time (the late ’90s), I published my first chapbook, Forge of Words a Forest, with Jensen Daniels, an imprint of Talisman House.

All these experiences were important for a young poet, because they exposed me to multiple poetry scenes throughout the United States and Europe—different ways a poem could exist in the world—as well as to certain trends in poetry at the time. They also led me to correspond with editors and writers I admired—not only Peter O’Leary and Kevin Killian, but also older writers like Gustaf Sobin, William Bronk, and Gerrit Lansing—again, correspondence can be an education in poetry all its own. John Wieners was an especially big influence on me at the time; I carried his Selected Poems, 1958-1984 (Black Sparrow, 1986) everywhere, reading it on trains, buses, park benches, whenever I had a chance. I’ll never replace my worn-out copy since there are so many memories associated it with it. I remember seeing Wieners read with Eleni Sikelianos in the late ‘90s at the old Teachers and Writers Collaborative space on Union Square; I went up to him afterwards and told him I had just picked up Behind the State Capitol, or Cincinnati Pike (Good Gay Poets, 1975) and he said, “Hold on to it, it’ll be valuable someday.” The 1969 Angel Hair edition of his Asylum Poems is also one of my most treasured books. I’m glad there’s growing interest in Wieners’s poetry, with a collected poems edited by Robert Dewhurst and a biography of him in the works.

RT: What about translating—when did that begin?

PV: Well, I didn’t seriously start translating books until 2014, when I realized I was drawn to writers such as Antonin Artaud and Sandro Penna, along with certain voices from the ancient world like Catullus, because their writings in one way or another were centered on an exploration of the body. Filmmaking helped me change my thinking about my writing (which in my late twenties was somewhat abstract) by leading me out to the streets, where I became involved in situations that demanded a dialogue or some form of intervention; when I attempted to extend these practices to writing, the result was an interest in opening up conversations through translation—dialogues with writers who were literary “outcasts” and for whom the sexual body is an important subject. This includes the five Classical Roman poets I translated in Let the Games Begin (Talisman House, 2015) and especially Catullus, who I tackled with Catullus: Versions (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017), as well as the more modern writers I work on.

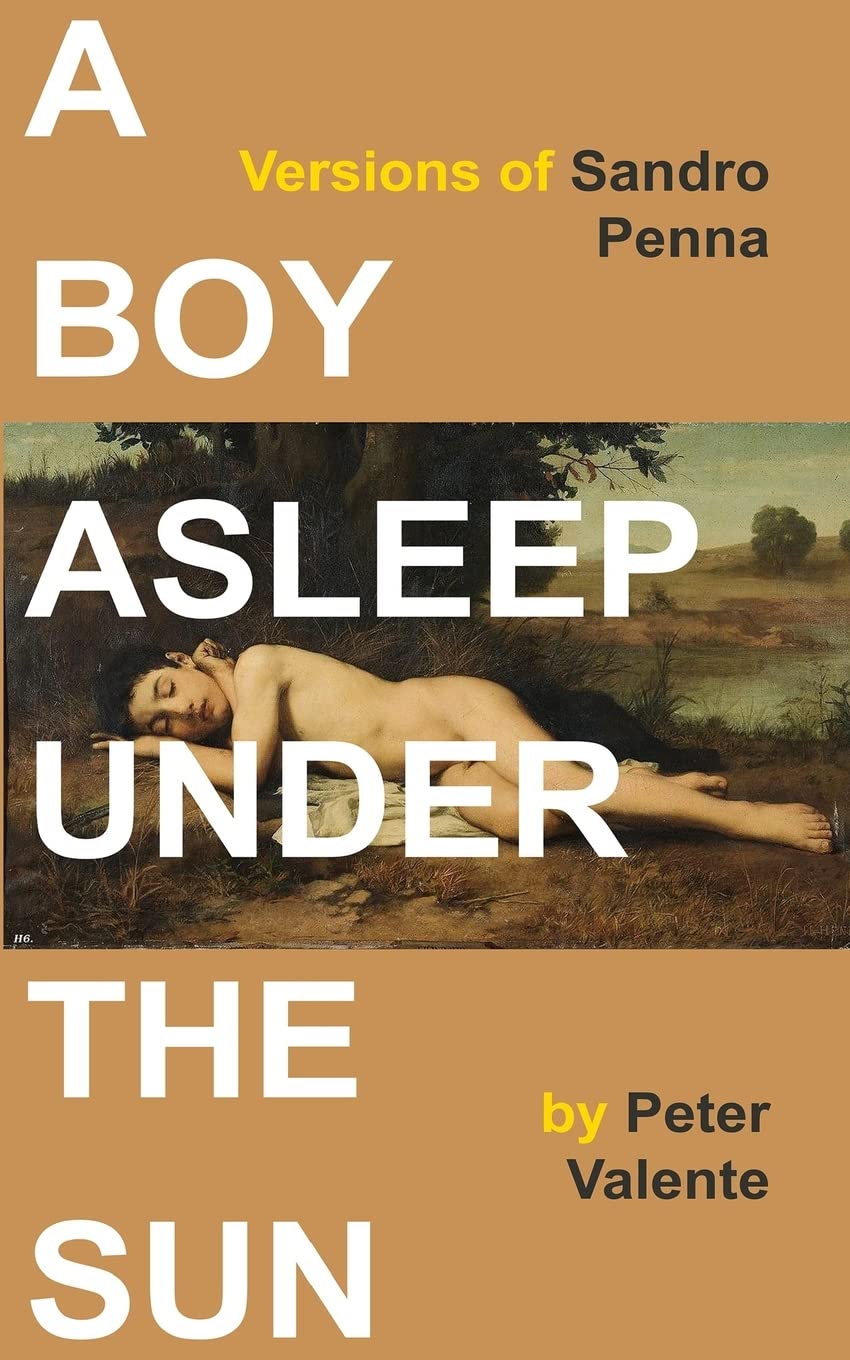

RT: A perfect way to segue into talking about the Italian poets you’ve translated over the past decade. What led to the creation of A Boy Asleep Under the Sun: Versions of Sandro Penna (Punctum Books, 2014)?

PV: Penna is not well known in the U.S.; there were only a few translations of his work in English, all hard to find. Pasolini said that despite being a great poet, Penna was “destined to be a poet at the margins, not known, even despised.” The times have certainly changed somewhat—gay poets are more visible now than they’ve ever been—but there is still much more recovery work to be done; so many writers unjustly ignored in their time have poems that deserve a second look. Penna was openly gay and when Pasolini first arrived in Rome in 1950, he sought him out; they became good friends and frequent companions, their bond strengthened by their mutual love for young men (they both loved the ragazzi that prowled the outskirts of Rome). Penna also knew Eugenio Montale, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 1975, but Montale objected to the homosexual content of Penna’s work, which led to a rift in their friendship. Penna published very little in the ’60s; the last book he approved for publication, The Sleepless Traveler, was published a month after his death in Rome on January 21, 1977. I think Penna’s various silences and refusals to publish were his way of showing that he didn’t care about how his work was received in academic circles. Anyway, when I delved into Penna’s poems I found them to be utterly brilliant, so I knew I had to translate him.

RT: Since you brought up Pasolini, let’s talk about him next; you’ve published translations of his poems in places like Jacket and The Baffler. Will there ever be a book of this work—and what is it like translating such an iconic artist, as compared to poets who are lesser known here in the U.S.?

PV: I don’t presently have plans to publish a book of my Pasolini translations, but I find him continually fascinating. Throughout his life he was an outspoken critic of what he believed was destroying Italy. In the United States, he is largely seen as a civic poet, but I wanted to focus on other kinds of poems. For example, his collection The Hobby of the Sonnet contains a series of love poems that show he was a lyric poet of the highest order. It was an eye-opening experience translating these poems, which have a fascinating backstory: While shooting La Ricotta (1963), Pasolini met the young man who would become his intimate companion for many years, Giovanni (“Ninetto”) Davoli; he was fourteen when he met Pasolini, who had just turned forty. Soon Ninetto became part of Pasolini’s entourage and began appearing in his films, starting with The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) and culminating with The Arabian Nights (1974). “In me, he found the naturalness of the world he knew growing up,” Ninetto said, and I think that’s true: This was the world that Pasolini saw devastated by the changes Italy was undergoing in the ’60s. During the filming of The Canterbury Tales (1972), however, Ninetto told Pasolini that he intended to marry (which he did, in January 1973), promising that nothing fundamental would change as a result. But Pasolini was inconsolable. The series of poems he began in the fall of 1971, The Hobby of the Sonnet, charts the series of emotional upheavals Pasolini underwent during this time. After the wedding Pasolini’s anger subsided, and in 1973 he wrote, “seeing that you have retained a little love for me / exclusively, this means everything.” Desire had given way to affection and loyalty. In The Arabian Nights Pasolini cast Ninetto as Aziz, a character he described as “joy, happiness, a living ballet.” Ninetto’s first son was named Pier Paolo. The Hobby of the Sonnet wasn’t published in Italy until after Pasolini’s murder in 1975, and while I and others have published translations of some of the poems, the entire sequence has never been published in English as far as I know.

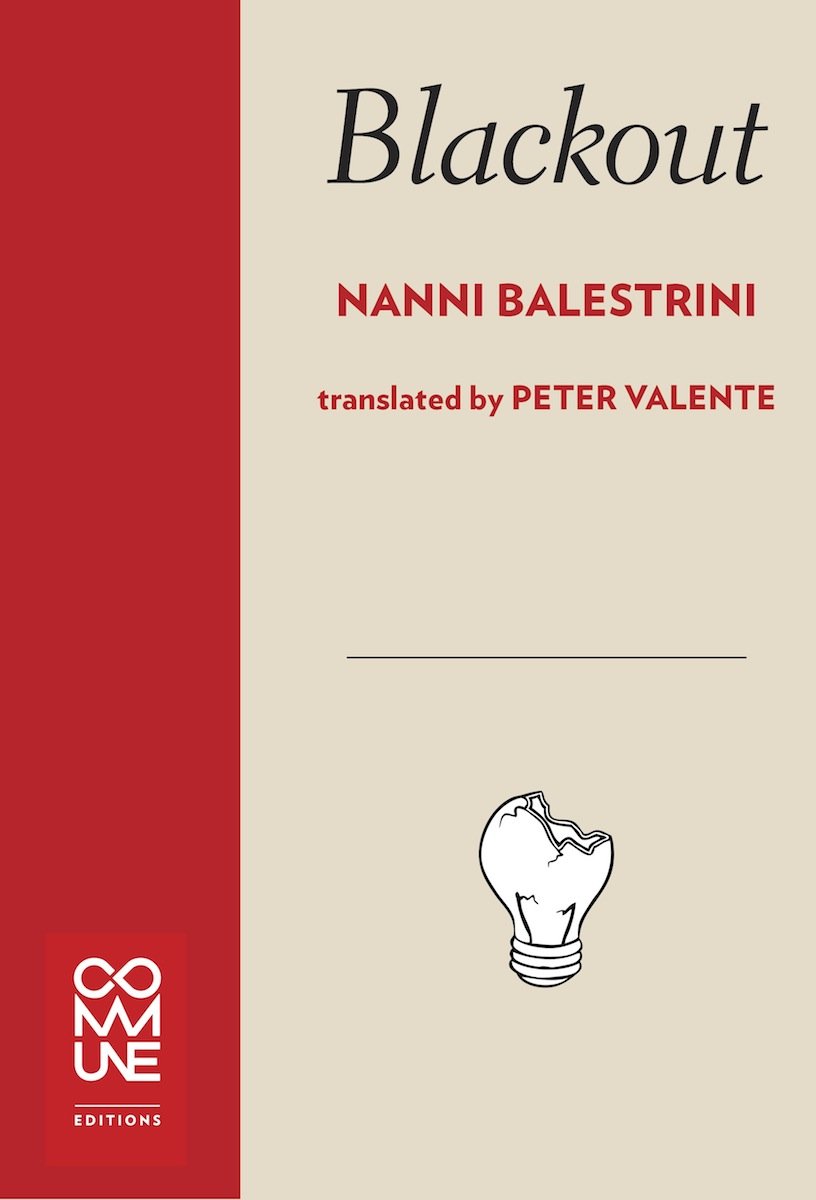

RT: And finally, you’ve given us Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions, 2017). How did you discover his work?

RT: And finally, you’ve given us Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions, 2017). How did you discover his work?

PV: I first discovered Balestrini’s poems in the anthology The Promised Land: Italian Poetry After 1975 (Sun & Moon Press, 1999). I had been aware of his novels in English translation published by Verso, but no book of his poetry had yet been translated—so I decided to translate this long poem, which is not only one of Balestrini’s best books but also extremely relevant to our time. Blackout is a requiem for the generation of 1968, whose hopes and ideals were exhausted by the time of the poem’s composition in 1979. The impetus for the poem was the New York City power outage of 1977, which lasted for over twenty-four hours and received widespread media attention because of episodes of violence and looting—but the historical events with which Blackout is concerned (and about which it is critical) span the revolutionary movement in Italy from 1969 to 1979, which involved not only university students but eventually the entire Italian working class, who took part in strikes, demonstrations, and acts of sabotage. Workers fought with fascists and police in Rome, Milan, Turin—and lives were lost amidst the violence.

As a result of mass arrests in 1979, Balestrini was indicted and fled to France; there he began to collect the materials that would eventually become Blackout. He was essentially creating a map to understand the political climate, examining the sequence of historical events whose consequence was repression and asking why no further revolutionary action is possible. In a sense, Blackout faithfully records the end of a world, the extraordinary period of creativity and hope that had characterized the late ’60s and early ’70s. But as much as it is an elegy, Blackout is also a call to action for future generations to counter the ever-present problem of power. We must collapse distinctions which enforce the duality of superior/inferior; we must imaginatively interrupt and redirect the flow of knowledge, moving through fissures and gaps to arrive at a new language and way of perceiving the world. The threat of physical and psychic death is all too real in this unstable political climate.

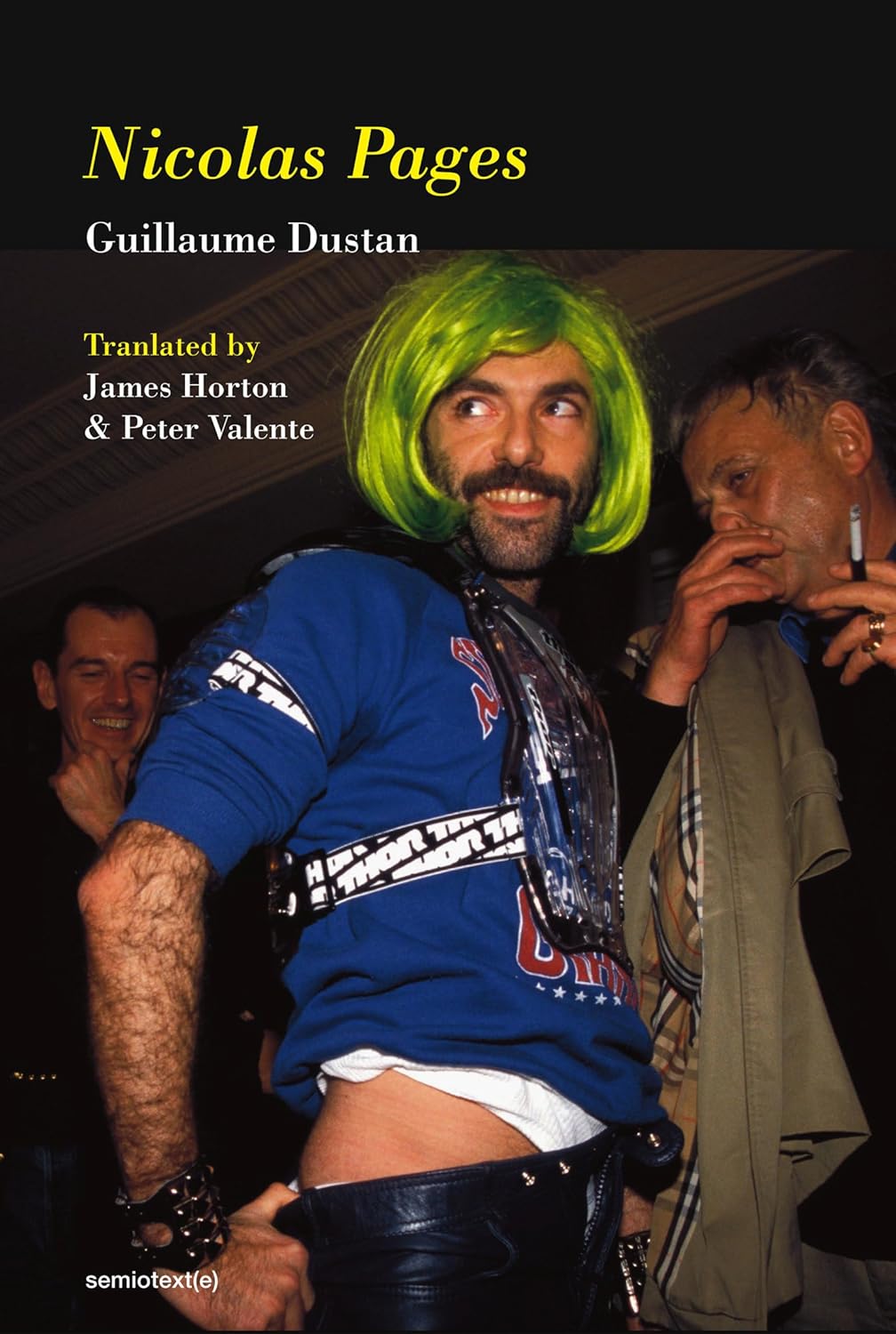

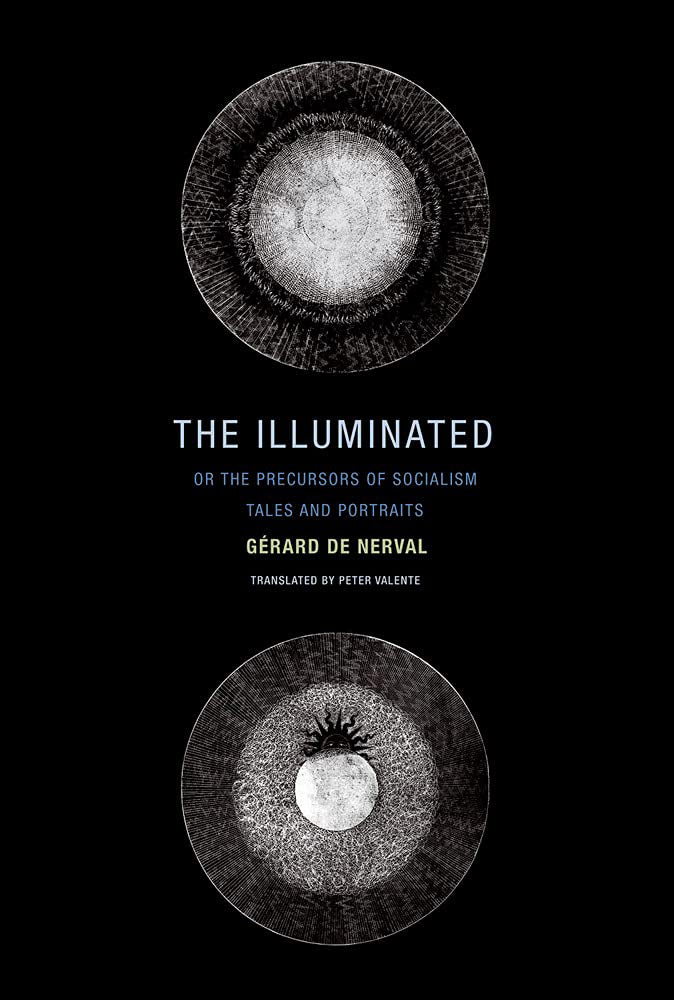

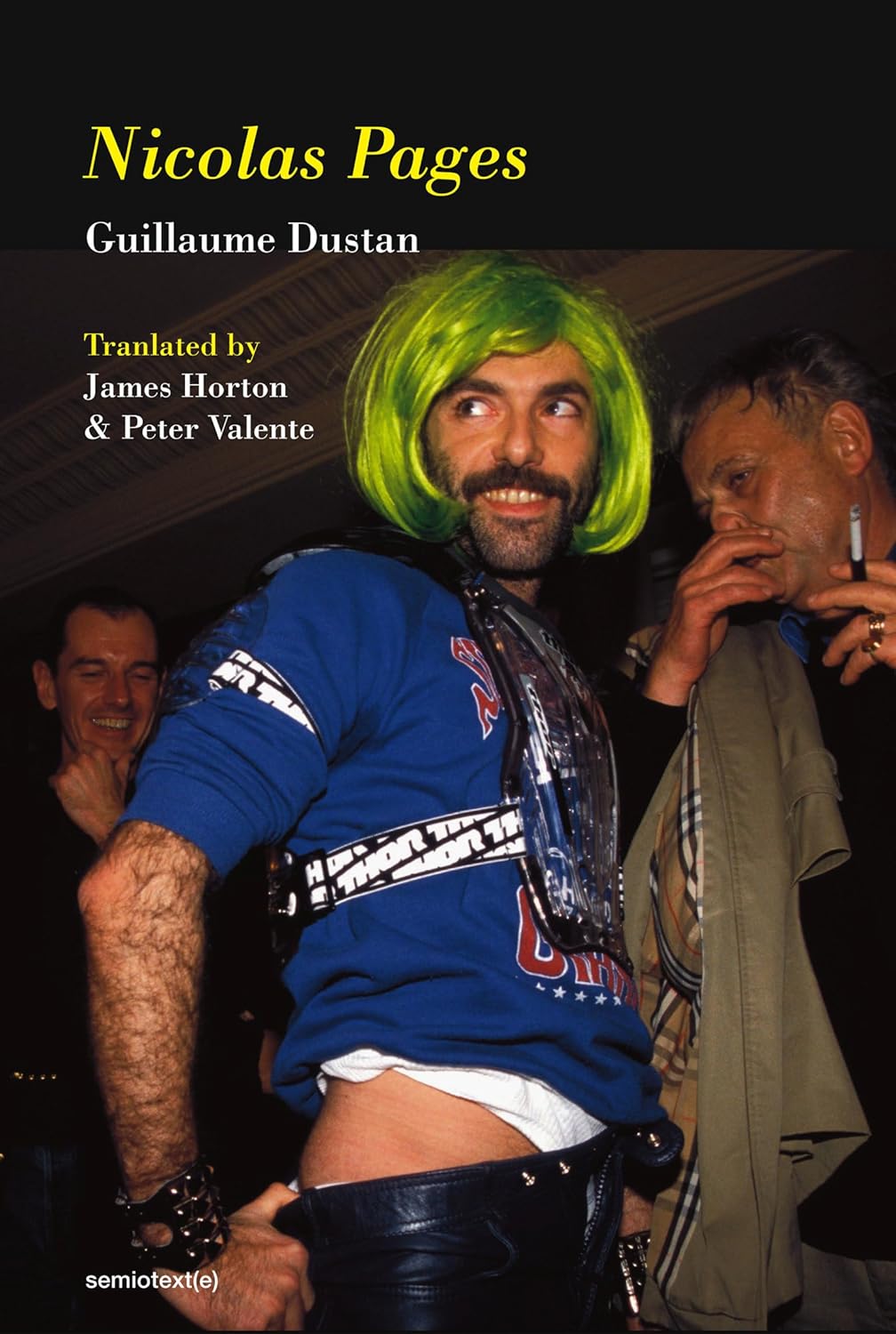

RT: You also translate from the French; two of your most recent translations are the novel Nicolas Pages (Semiotexte, 2023) by Guillaume Dustan and The Illuminated, or The Precursors of Socialism: Tales and Portraits (Wakefield Press, 2022) by Gerard de Nerval. What can you tell us about these titles?

PV: I translated The Illuminated because I considered it an important book that filled a gap in Nerval studies. Collectively, its narratives of six men show Nerval’s attempt to map an alternative history of the eighteenth century through the eyes of these visionaries. They also show that Nerval’s descents into madness (he suffered from bouts of mental illness throughout his life) were followed by ascents back to reality that resulted in a clearer vision of truth; as he wrote, “Is there not something of reason to be extracted from madness?” And so, Nerval embarked on these portraits, extracting a kind of moral from each of these figures’ confrontation with the abyss opened by “the death of God,” in a century that relegated visionaries to the position of outcasts.

PV: I translated The Illuminated because I considered it an important book that filled a gap in Nerval studies. Collectively, its narratives of six men show Nerval’s attempt to map an alternative history of the eighteenth century through the eyes of these visionaries. They also show that Nerval’s descents into madness (he suffered from bouts of mental illness throughout his life) were followed by ascents back to reality that resulted in a clearer vision of truth; as he wrote, “Is there not something of reason to be extracted from madness?” And so, Nerval embarked on these portraits, extracting a kind of moral from each of these figures’ confrontation with the abyss opened by “the death of God,” in a century that relegated visionaries to the position of outcasts.

Published in 1999, Nicolas Pages marks a departure from the Sadean preoccupations of Dustan’s previous three novels. It is in essence a love story. The writing is trashy, corporeal, frantic, but also collage-like, encyclopedic, philosophic: Dustan includes articles that he initially wrote for various magazines on the history of “house” music, on the history of homosexual virility since the 1970s, on modes of transmission and repression of SM practices, on the links between literature and sexuality, and on the notion of gay literature. It is a call for gay rights, a vibrant plea for autofiction, a reconciliation with his homosexual identity, a message of hope and energy, and a hymn to life, humanity, love, pleasure, and desire. Inconstant, insolent, anti-conformist, and provocative, Dustan inaugurates a “gay literature” that is no longer painful or shameful but epicurean and cheerful without lapsing into idealism.

RT: How did The Artaud Variations (Spuyten Duyvil, 2014) come about?

PV: Essentially as an experiment. I had been interested in Artaud ever since I first read his work in college. Much later, I encountered Ezra Pound’s idea of “criticism by translation,” which required “an intense penetration of the author’s sense” and “an exact projection of one’s psychic contents.” I was thinking about these ideas when I wrote The Artaud Variations. I combined my own writing, as a kind of commentary, with my translations of sections from Artaud’s work. Writing this book was an intense and almost overwhelming experience. Sylvère Lotringer (1938-2012), the publisher of Semiotext(e), was one of the first to understand what I was doing, and he kindly wrote a blurb for the book that captures what I was going for: “Peter Valente has done everything that a translator/reader of Artaud shouldn’t do: he crossed the line and merged his own writing with the original. But he did it to such a mind-blowing extreme that Artaud’s voice becomes his own.”

RT: Since then, you’ve clearly doubled down on your devotion to Artaud, and have released three books from the London-based publisher Infinity Land Press: 2020’s Succubations and Incubations: Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud (1945-1947), co-translated with Cole Heinowitz, and two books in 2023, The New Revelations of Being and Other Mystical Writings and Obliteration of the World: A Guide to the Occult Belief System of Antonin Artaud. Can you give us a quick tour through these titles?

PV: Succubations and Incubations contains a selection of letters (1945-1947) from Artaud’s consummate work, Suppôts et Supplications [Henchmen and Torturings], which provides readers with a vivid, uniquely intimate view of Artaud’s final years. They show Artaud at his most exposed, and perhaps also his most explosive, tragic, sad, even humorous. Commenting on and elaborating key themes from his earlier writing while venturing into new territory, Artaud recounts his torture and violation in asylums, his crucifixion two thousand years ago in Golgotha, his deception by occult initiates and doubles, and his intended journey to Tibet—where, aided by his “daughters of the heart,” he will finally put an end to these “maneuvers of obscene bewitchment.” Artaud also speaks of his plan to create a “body without organs” and extends this idea to the visual arts, where he argues that painting and drawing must wage a ceaseless battle against the limits of representation. There is an unmistakable unity of vision that permeates the letters.

The New Revelations of Being and other Mystical Writings contains texts written by Artaud between 1933-1937, works that explore astrology, alchemy, Eastern philosophies, Christian ritual and magic, the Tarot, and the civilizations of India and Mexico. Artaud’s extensive reading and thinking on metaphysics and religion produced “Notes on Oriental, Greek and Indian Cultures.” Also included are the important essays, “Mexico and Civilization,” “The Eternal Betrayal of the Whites,” “The Life and Death of Satan the Fire” and “The Breath that Returns to God…” But the central text in this volume is The New Revelations of Being. In this work, Artaud is the “Revealed One,” the madman and fool of the Tarot, who possesses secret knowledge which he believes will allow him to enact his apocalyptic vision of a world transformed through destruction.

The New Revelations of Being and other Mystical Writings contains texts written by Artaud between 1933-1937, works that explore astrology, alchemy, Eastern philosophies, Christian ritual and magic, the Tarot, and the civilizations of India and Mexico. Artaud’s extensive reading and thinking on metaphysics and religion produced “Notes on Oriental, Greek and Indian Cultures.” Also included are the important essays, “Mexico and Civilization,” “The Eternal Betrayal of the Whites,” “The Life and Death of Satan the Fire” and “The Breath that Returns to God…” But the central text in this volume is The New Revelations of Being. In this work, Artaud is the “Revealed One,” the madman and fool of the Tarot, who possesses secret knowledge which he believes will allow him to enact his apocalyptic vision of a world transformed through destruction.

Obliteration of the World contains my own essays exploring the hermetic side of Artaud’s thought, focusing on a series of letters written, late in his life, to André Breton, Georges Braque, Marthe Robert, Anie Besnard, and Collette Thomas. “Artaud’s Sacred Triad” uses the Qabalah and ideas about the Tarot to deepen ideas about Artaud’s sexuality and magick. “Cubism and the Gnostic” presents Artaud’s criticism of Georges Braque, which goes beyond mere aesthetics to question the essence of representation. “Artaud’s Book of the Dead” explores the Tibetan idea of the afterlife and Artaud’s relation to it; for him, the body that has evolved through time and suffered ceaseless persecutions both in life and in the afterlife is the corrupt body born of the spirit of God—thus, God is one of Artaud’s greatest enemies. “The Incestuous Father and His Daughters of the Heart” engages Artaud’s relation to the various women in his life; to these women, Artaud was alternately sympathetic and cruel, manipulative and romantic. The final essay is concerned with Artaud’s travels in Mexico, focusing on the importance to him of the mystical staff of St. Patrick. These essays were the result of years of thinking about Artaud’s work.

Obliteration of the World contains my own essays exploring the hermetic side of Artaud’s thought, focusing on a series of letters written, late in his life, to André Breton, Georges Braque, Marthe Robert, Anie Besnard, and Collette Thomas. “Artaud’s Sacred Triad” uses the Qabalah and ideas about the Tarot to deepen ideas about Artaud’s sexuality and magick. “Cubism and the Gnostic” presents Artaud’s criticism of Georges Braque, which goes beyond mere aesthetics to question the essence of representation. “Artaud’s Book of the Dead” explores the Tibetan idea of the afterlife and Artaud’s relation to it; for him, the body that has evolved through time and suffered ceaseless persecutions both in life and in the afterlife is the corrupt body born of the spirit of God—thus, God is one of Artaud’s greatest enemies. “The Incestuous Father and His Daughters of the Heart” engages Artaud’s relation to the various women in his life; to these women, Artaud was alternately sympathetic and cruel, manipulative and romantic. The final essay is concerned with Artaud’s travels in Mexico, focusing on the importance to him of the mystical staff of St. Patrick. These essays were the result of years of thinking about Artaud’s work.

RT: As you pointed out, this work focuses on late-period Artaud, to which translator-scholars like Clayton Eshleman and Stephen Barber have also drawn attention. What is it about this phase of Artaud’s life and work that is so challenging?

PV: I remember reading in Clayton Eshleman’s introduction to his translation of Artaud, Watchfiends & Rack Screams: Works From The Final Period (Exact Change, 2004), that “there are two major projects facing future Artaud translators, the 300-page Suppôts et Supplications (Volume XIV) presented in two books, which Artaud considered to be his summational work; and the Cahiers de Rodez (Volume XV-XXI), over two thousand pages, worked at daily throughout Artaud’s recovery period in Rodez. There are also four volumes of notebook material from Artaud’s last two years in Paris.” So that led me to try to tackle thinking about and translating some of this work. Most U.S. readers only know Artaud from Jack Hirschman’s Artaud Anthology (City Lights, 1965) and Susan Sontag’s and Helen Weaver’s Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976) but even that book, though more well-rounded than Hirschman’s, “proposes that Artaud’s importance lies in the pre-Rodez work,” as Eshleman writes.

The later work is challenging: Artaud’s apocalyptic vision for mankind led him on a journey, beginning in Mexico in 1936 and ending, tragically, in Ireland in 1937, with a mental breakdown and silence. After the fateful journey to Ireland, he was placed in a straitjacket and eventually sent to the Rodez asylum. In the late work we see Artaud reconstructing a life that was destroyed. He develops a vast cosmology in which there are demonic entities and an entire panoply of beings that constitute the spirit world, and in which occurs a dramatic fight between these entities and mankind, which Artaud insisted had nothing to do with the spirit. It is a world completely unlike the surrealist and visionary one most U.S. readers associate with Artaud—and it is a cosmology that he ultimately rejects in favor of silence: In 1948, Artaud wrote: “At this moment, I want to destroy my thought and my mind. Above all, thought, mind and consciousness. I do not want to suppose anything, admit anything, enter into anything, discuss anything…”

RT: Do you have any more Artaud projects in the hopper?

PV: Later this year, Infinity Land Press will publish my translation of The True Story of Artaud-Mômo, which contains the complete text of Artaud’s final lecture, given in Paris on the night of January 13, 1947. It was his last public performance, one in which he forcefully ruptured all received and polite notions of performance, lecture, or even theatre–he pushed himself and his viewers past the realm of what could be comfortably absorbed. This work became an important reference point for various post-war intellectuals and artists, such as the Lettrists, the New Realists, the Beat Generation, and the movement of action poetry. What makes the text so riveting and powerful is that unlike in his other writings, Artaud is summing up a lifetime of experiences and pain at the hands of society and doctors—it is the closest thing we have to an autobiography.

RT: As if writing and translating weren’t enough, you also work in visual media. Why did you decide to make films?

PV: It came about by accident. In 2010 I started showing films (from my own collection of DVDs) twice a week at a nursing home in Jersey; although I was writing, I wasn’t publishing books. One night at the home, I met someone who had a Bolex camera and wanted to shoot a film; with no working script, we shot a film over a weekend, Liminal, that was shown at Anthology Film Archives. Later I made my own films, but without any money—I had to use what was readily available. I shot my first few films with a small point-and-shoot Canon camera and a few friends; in my later films, I dispensed with “actors” entirely, using myself or random people on the street when needed. I usually followed my instinct rather than a prepared script—in fact, I’ve never made a film with a script of any kind. I start with an idea and improvise from that, like free jazz musicians such as Cecil Taylor and Derek Bailey. Georges Méliès had to improvise his films during the early age of cinema, and the result was magical: A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904) hold up even to this day. Improvisation governs almost all aspects of my life, and certainly those that have to do with artistic creation.

RT: You also have published photographic work—tell us about Street Level (Spuyten Duyvil, 2015).

PV: During the summer of 2012, I filmed, alone and with a cheap camera, homeless vets, former drug addicts, and gang members in New Jersey and on the Lower East Side. I was planning to make a documentary to be called Street Level; the film was never completed, but the book of the same name featured stills from the film. Despite considerable risk, I was trying to capture the language and face of despair and anger otherwise silenced in the media. There is, as we all know, an increasing divide between the everyday “normal” life of most Americans and the “extraordinary” life of the privileged, but many of the men and women I filmed live outside these two worlds—and thus they are invisible. But they have something to tell us, and we must listen. They have the possibility, as we all do, of being transformed. This would mean seeing all of us connected, where there are no false dividing lines, no mysterious Others, but a single body of which we are a part, working together and accepting our differences.

RT: Let’s close with some other strands of what you do in the writing world, starting with fiction. Can you speak a bit about your novella “Parthenogenesis”?

PV: “Parthenogenesis” was my attempt at writing a kind of science-fiction novella. It includes subjects like telepathy, cyborg bodies, time travel, pop culture, and class critique; in terms of narrative, I wanted to create a story that is essentially a series of fragments, moving between the past and the present—the impression of a narrative pulsing underneath rather than immediately apparent. That pulse, like a heartbeat, dark and violent but also transformative, drives the narrative toward the possibility of revolution and magic. A character in the book says: “Magic draws from the forbidden…the first magical act is becoming aware that I AM a self…distinct from others who carry the same social role.” In other words, the first act of revolution takes place within. “Parthenogenesis” and “Plague in the Imperial City” were published together as Two Novellas (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017).

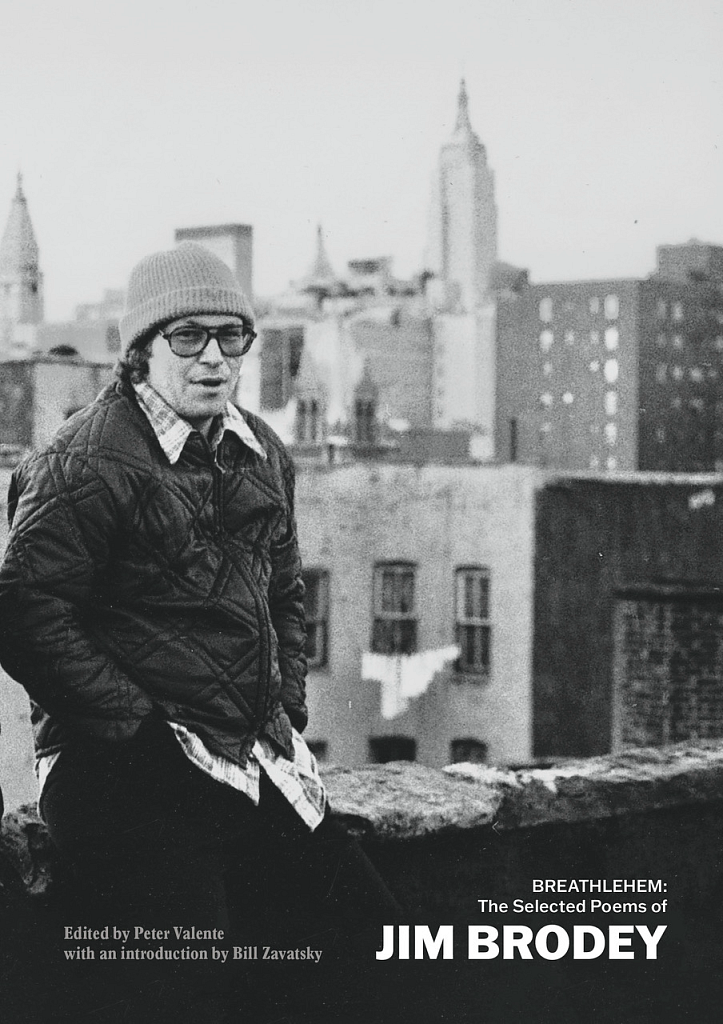

RT: Among the plethora of books you’ve recently published are A Credible Utopia: Essays on Selected Films of Werner Schroeter (Punctum, 2022), and a poetry volume you edited, Breathlehem: The Selected Poems of Jim Brodey (Local Knowledge, 2024). Both are, in a sense, homages to artists largely unknown beyond devotees of film and poetry. How did these projects come about?

RT: Among the plethora of books you’ve recently published are A Credible Utopia: Essays on Selected Films of Werner Schroeter (Punctum, 2022), and a poetry volume you edited, Breathlehem: The Selected Poems of Jim Brodey (Local Knowledge, 2024). Both are, in a sense, homages to artists largely unknown beyond devotees of film and poetry. How did these projects come about?

PV: Regarding the Schroeter book, I attended a retrospective of his films in 2012 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; I had been aware of his name from having watched some of the so-called New German Cinema, but I was immediately attracted to Schroeter’s films because they seemed so unusual compared to the other German films at the time. I admired their theatricality and almost unhinged emotional quality; they seemed improvised and irreverent. Schroeter was a kind of romantic with both feet in the real world—his films don’t take themselves too seriously, even when dealing with serious subjects like the nature of love and death.

Also, as a filmmaker, I’ve worked in 8mm, 16mm, and digital, so when viewing his films, I asked myself questions like: How did he get that lighting to produce such an image? What kind of film did he use? What kind of camera? I also admired his use of texts from literature, such as the Songs of Maldoror by Lautréamont, which Schroeter used in both The Death of Maria Malibran and a later film, Deux. And I admired the way he used music to comment on a character’s thoughts, or to conflict with what is on the screen; most of my films do not contain dialogue but I made extensive use of different kinds of music, from opera to popular music to jazz. I imagine Schroeter must have been aware of Kenneth Anger’s use of music in his films, the way it comments on the images and adds another dimension to what one is seeing on the screen. So, I approached Schroeter from the viewpoint of a filmmaker first, and not an academic.

As for Jim Brodey: It’s been thirty years since Hard Press published Heart of the Breath, a collection of Brodey’s poems edited by Clark Coolidge, and all his individual books remain out of print—so I just thought it was time for a Selected Poems to bring his work back into circulation for readers. Breathlehem contains selections from all of Brodey’s work including some poems that only appeared in magazines and were never collected in a book. I also included numerous photos of Brodey, both alone and in the company of other poets. My aim was to document an active and exciting period in the New York poetry world that Jim Brodey was a part of—as well as to serve as a reminder that he was and is one of our best poets.

As for Jim Brodey: It’s been thirty years since Hard Press published Heart of the Breath, a collection of Brodey’s poems edited by Clark Coolidge, and all his individual books remain out of print—so I just thought it was time for a Selected Poems to bring his work back into circulation for readers. Breathlehem contains selections from all of Brodey’s work including some poems that only appeared in magazines and were never collected in a book. I also included numerous photos of Brodey, both alone and in the company of other poets. My aim was to document an active and exciting period in the New York poetry world that Jim Brodey was a part of—as well as to serve as a reminder that he was and is one of our best poets.

RT: What are you working on next?

PV: I’m currently editing a series of texts on the filmmaker Harry Smith. My experience in film had led me to working as a proofreader and general editor and I also helped to get photos for the reissue of Paola Igiori’s American Magus: Harry Smith (originally published by Inandout Press, 1996) that Semiotexte published in 2022. While working on that book, I came into contact with many people who knew him, and this resulted in my putting together a collection of texts, photographs, letters, and even an unpublished document by Harry. The book is going to be published by Inner Traditions in 2025. I’ll also have a new book of reviews and essays in 2025 from Punctum Books; that will include essays on John Wieners, Jack Spicer, and David Wojnarowicz, as well as on John Ruskin and Gavin Douglas’ translation of the Aeneid. The book will also include reviews of books by Will Alexander, Bernadette Mayer, and Cookie Mueller. After that, who knows?

The New Revelations of Being and other Mystical Writings contains texts written by Artaud between 1933-1937, works that explore astrology, alchemy, Eastern philosophies, Christian ritual and magic, the Tarot, and the civilizations of India and Mexico. Artaud’s extensive reading and thinking on metaphysics and religion produced “Notes on Oriental, Greek and Indian Cultures.” Also included are the important essays, “Mexico and Civilization,” “The Eternal Betrayal of the Whites,” “The Life and Death of Satan the Fire” and “The Breath that Returns to God…” But the central text in this volume is The New Revelations of Being. In this work, Artaud is the “Revealed One,” the madman and fool of the Tarot, who possesses secret knowledge which he believes will allow him to enact his apocalyptic vision of a world transformed through destruction.

The New Revelations of Being and other Mystical Writings contains texts written by Artaud between 1933-1937, works that explore astrology, alchemy, Eastern philosophies, Christian ritual and magic, the Tarot, and the civilizations of India and Mexico. Artaud’s extensive reading and thinking on metaphysics and religion produced “Notes on Oriental, Greek and Indian Cultures.” Also included are the important essays, “Mexico and Civilization,” “The Eternal Betrayal of the Whites,” “The Life and Death of Satan the Fire” and “The Breath that Returns to God…” But the central text in this volume is The New Revelations of Being. In this work, Artaud is the “Revealed One,” the madman and fool of the Tarot, who possesses secret knowledge which he believes will allow him to enact his apocalyptic vision of a world transformed through destruction. Obliteration of the World contains my own essays exploring the hermetic side of Artaud’s thought, focusing on a series of letters written, late in his life, to André Breton, Georges Braque, Marthe Robert, Anie Besnard, and Collette Thomas. “Artaud’s Sacred Triad” uses the Qabalah and ideas about the Tarot to deepen ideas about Artaud’s sexuality and magick. “Cubism and the Gnostic” presents Artaud’s criticism of Georges Braque, which goes beyond mere aesthetics to question the essence of representation. “Artaud’s Book of the Dead” explores the Tibetan idea of the afterlife and Artaud’s relation to it; for him, the body that has evolved through time and suffered ceaseless persecutions both in life and in the afterlife is the corrupt body born of the spirit of God—thus, God is one of Artaud’s greatest enemies. “The Incestuous Father and His Daughters of the Heart” engages Artaud’s relation to the various women in his life; to these women, Artaud was alternately sympathetic and cruel, manipulative and romantic. The final essay is concerned with Artaud’s travels in Mexico, focusing on the importance to him of the mystical staff of St. Patrick. These essays were the result of years of thinking about Artaud’s work.

Obliteration of the World contains my own essays exploring the hermetic side of Artaud’s thought, focusing on a series of letters written, late in his life, to André Breton, Georges Braque, Marthe Robert, Anie Besnard, and Collette Thomas. “Artaud’s Sacred Triad” uses the Qabalah and ideas about the Tarot to deepen ideas about Artaud’s sexuality and magick. “Cubism and the Gnostic” presents Artaud’s criticism of Georges Braque, which goes beyond mere aesthetics to question the essence of representation. “Artaud’s Book of the Dead” explores the Tibetan idea of the afterlife and Artaud’s relation to it; for him, the body that has evolved through time and suffered ceaseless persecutions both in life and in the afterlife is the corrupt body born of the spirit of God—thus, God is one of Artaud’s greatest enemies. “The Incestuous Father and His Daughters of the Heart” engages Artaud’s relation to the various women in his life; to these women, Artaud was alternately sympathetic and cruel, manipulative and romantic. The final essay is concerned with Artaud’s travels in Mexico, focusing on the importance to him of the mystical staff of St. Patrick. These essays were the result of years of thinking about Artaud’s work.

As for Jim Brodey: It’s been thirty years since Hard Press published Heart of the Breath, a collection of Brodey’s poems edited by Clark Coolidge, and all his individual books remain out of print—so I just thought it was time for a Selected Poems to bring his work back into circulation for readers. Breathlehem contains selections from all of Brodey’s work including some poems that only appeared in magazines and were never collected in a book. I also included numerous photos of Brodey, both alone and in the company of other poets. My aim was to document an active and exciting period in the New York poetry world that Jim Brodey was a part of—as well as to serve as a reminder that he was and is one of our best poets.

As for Jim Brodey: It’s been thirty years since Hard Press published Heart of the Breath, a collection of Brodey’s poems edited by Clark Coolidge, and all his individual books remain out of print—so I just thought it was time for a Selected Poems to bring his work back into circulation for readers. Breathlehem contains selections from all of Brodey’s work including some poems that only appeared in magazines and were never collected in a book. I also included numerous photos of Brodey, both alone and in the company of other poets. My aim was to document an active and exciting period in the New York poetry world that Jim Brodey was a part of—as well as to serve as a reminder that he was and is one of our best poets.