by Jane Rosenberg LaForge

After meeting her grandfather for only the second time when she was in college, Summer Brenner thought, “Maybe connecting the pieces of my family has always been my duty.” Her new memoir, Dust (Spuyten Duyvil, $20), draws together the disparate branches of her family, which include her brilliant father, her prickly mother, and her little brother, David, ultimately delivering a troubling saga of frustrated ambitions, intra-family feuding, white privilege punctuated by anti-Semitism, and closely guarded secrets. Some secrets revolve around her father, others engulf her mother, but most of all, they separate Brenner from her brother, who comes to provide one of the most honest and affecting relationships of her life.

Brenner was raised in Georgia but has lived in the Bay Area for most of her adult life. She is the author of sixteen previous books, among them poetry collections, crime novels, and books for young adults, and her work has been included in numerous anthologies, from Rising Tides: 20th Century Women Poets (Simon & Schuster, 1973) to 2020’s Berkeley Noir (Akashic Books). In the following interview, she discusses the many strands that make up Dust.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge: Portrayals of Jewish Americans are often replete with stereotypes when it comes to mothers and fathers—the larger-than-life Jewish mother, the brilliant but ineffectual father. Did you consider the problem of stereotyping when writing Dust—and if so, did you feel a responsibility to overcome it?

Summer Brenner: I didn’t consciously try to avoid anything, but maybe it can be explained this way: Stereotypes and archetypes are typically reductive, with recognizable signs that let a reader automatically draw predictable, foregone, even formulaic conclusions. I tried to draw fully individual portraits with minimal but very precise brushstrokes.

Although my parents didn’t avoid their Jewish identity, it wasn’t foremost for either of them. I think the day after my father’s Bar Mitzvah (in a small mountain town in western North Carolina) he declared himself an atheist, and the next year at fourteen he left home for university. My mother’s father’s eventual wealth paved his daughters’ way for assimilation. Of the families started by the three sisters, mine was the least observant. Jewish holidays were celebrated at either my grandmother’s or aunt’s home. Lighting Hanukkah candles, a few words of Yiddish, membership at a Jewish country club, and Jewish summer camps were the most prominent Jewish markers of my youth.

JRL: How do reading and writing poetry influence your prose?

SB: For my first decade as a writer, I wrote only poetry; my first books were poetry collections. When I turned to prose, I thought I’d lost the poet inside me, but I’m relieved to say she has been resuscitated. Dust was very much written with poetry in mind: its rhythms and repetitions; its simple, almost childlike language; its short sentences, as if I’m reporting in real time (placing myself in the past as if I didn’t yet know what would happen). I like to say that I wrote looking forward, not back, which feels like a poetic device.

JRL: Was the childlike voice a conscious decision or something you discovered while writing Dust?

SB: Before I start a book, I usually find that I’m waiting for the particular voice of the project to emerge. I don’t know how or when it will happen. For example, for my book I-5, A Novel of Crime, Transport, and Sex (PM Press, 2009), which I’d call a very raw and feminist work, I had to wait four years—until I got so furious over the bombing of Iraq that I could transfer that fury into the voice of Anya, a young woman trafficked to the U. S. from Russia.

Once the voice begins to speak, that’s the beginning, and I can hold onto that voice until the book is finished. Some writers say they “found” their voice, or they can be “identified” by their voice; my writing doesn’t work like that. With Dust, the voice began to speak in the cemetery, in the first chapter. From there it wound back to my earliest memory of David: the day he came home from the hospital. And so on.

JRL: Why did you write the story of Dust as a memoir?

SB: Writing Dust as a memoir was a way to honor my brother after his death. As a fictional character, he could have appeared sensationalized, or derivative (I’m thinking of Benjy in The Sound and the Fury). A memoir allowed me to scrupulously tell his story. It also let me hold onto him and his memory without fabrication or elaboration. I consider this book more his than mine.

I have used family members as characters in my fiction, however, most notably in a collection of short stories, My Life in Clothes (Red Hen Press, 2010). My first novel (which remains unpublished) transpired over a week in the life of a Jewish family in Atlanta, each chapter recounting a day leading up to the bombing of the family’s temple. I’m not sure if it’s redeemable; the whole ended up less than the parts. In the early part of this century, I attempted a long family saga with versions of the stories in this memoir and fictional stories as well. Its working title is Leaving the Atlantic—when you’re raised on the eastern side of the continent, especially in the southern quadrant, it can feel like there’s a stranglehold on your identity.

JRL: Toward the end of Dust, you learn the secret of your brother’s disability—his official diagnosis. Had you known earlier—had anyone known earlier—would his situation have been any different? Would you have better understood your mother’s behavior? Or was keeping it a secret the best that could be done for him?

SB: David was born in 1949. As a boy, he went to a psychiatrist. I don’t know what happened there, but both my mother and I eventually concluded that David was probably autistic. However, in those years, autism was not a common diagnosis. Even in the medical reports from Mass General, the doctors don’t mention the possibility. From the beginning, no one was forthright about David’s actual condition—not to each other or to me. There were ongoing, dueling realities between experience and silence. I can’t be sure, but I believe that if David’s own needs and desires had been acknowledged and respected, his situation would have been different. He could have had a simple job and lived on his own. But that would have required honestly acknowledging his limitations. Our mother had fierce ambitions for him that included a kind of revenge on the world on his behalf. She never found a way to accept him for himself, which led to terrible pressures on him and delusional behavior for her. As for understanding my mother’s behavior, she sadly endured both guilt and blame, first for his developmental disabilities and then for his full-blown mental illness. It’s also true that in those years, mothers were especially blamed.

JRL: Could you write another memoir? Or perhaps I should ask, will you? You seem to have a wealth of other material.

SB: I do, and much of it exists already in manuscripts. Recently, I started a series called “Do You Ever Think of Me?”: profiles of people in my life, written in second person. I have a few dozen of them that straddle memoir and fiction. In 2022 several were published by above/ground press in Ottawa as a chapbook, Do You Ever Think of Me?

JRL: Do you feel that Dust is a decidedly Jewish memoir, a decidedly Southern memoir, or a combination of the two? Or were you trying to avoid those kinds of labels?

SB: It’s mostly a memoir about mental illness in a family that happens to be Southern and Jewish. However, those two elements are not superfluous. The combination of Southern and Jewish is still a curiosity to many. Because my family wasn’t observant, and their politics didn’t fit into the Dixie paradigm, and we were living in an apartheid state, and our synagogue was bombed, many seminal events were particular to those times in that place.

JRL: How much of Dust—or your life, if you’d like to take all of that in—do you consider a story about feminism? You don’t set out to become a caregiver, or to fulfill any feminine or feminist role, and yet where you wind up represents a kind of combination of the two.

SB: My mother was very independent—not in the least maternal or domestic. She didn’t cook or clean; she didn’t work. She loved clothes (I do, too), but she didn’t spend all her time shopping. Although she played cards (I do, too, mostly with my grandkids), she wasn’t a country club type. She didn’t participate in PTA. She didn’t even give us birthday parties. After my father died, she devoted herself to painting, and she became a truly wonderful and original artist (there’s a link on my website to her paintings). So already I had an unusual role model.

I went to my first Women’s Lib conference in the late ¢60s, and I loved listening to the brilliant, brave women I heard there. Most (all?) of my romantic relationships struggled with men’s expectations of me as cook, homemaker, sex kitten, wife. At a certain point I preferred to be a single mother, although it came with great financial hardship. I also preferred having drudge jobs rather than a career path. I was anti-bourgeois and anti-capitalist. And I loved being a mother, which compensated a lot for my own childhood. I think I was an ardent caregiver.

I am married now, and I’ve been married before. And while I’m not unkind, I’m also not very wifely. My husband and I live separately on the same lot and usually see each other in the evening after dinner. I feel extremely fortunate to have been born into a feminist worldview. While this book reveals certain elements of my development as an adult, other elements—entire decades of romance, motherhood, and employment—are absent. Also, I’m extremely political, an activist, and that’s not so apparent either. If you came to visit me now, you’d see the trappings of a comfortable life, because twenty years ago, I became a homeowner: After years of tramping around with my kids, living in cheap apartments and driving broken-down cars, I have a lovely house. Again, the fortune of circumstances.

JRL: Considering what’s happening now, it might surprise some readers that Dust contains no mention of Israel. Is there a reason for this? Were your parents not that invested or interested in Israel?

SB: The Holocaust and the atomic bomb were shadows over my generation. My father, however, was anti-Zionist. He was “anti” much of the status quo and more belligerently vocal about his opinions than his peers. I participated in Sunday school and was confirmed; there were no Bar/Bat Mitzvahs at our temple. I recall collecting small change for purchasing trees in Israel. Exodus, Gentleman’s Agreement, and The Diary of Anne Frank were my literary introductions to anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, and Israel. As my political understanding evolved, I had a vague sense that the horrors of the Holocaust had justified terrible things in the formation of the state of Israel. I think my father probably thought deeply about these things. But he died when I was only nineteen, and I never had a chance to talk with him. As I’ve aged, the shadows of the Holocaust and nuclear war have only darkened.

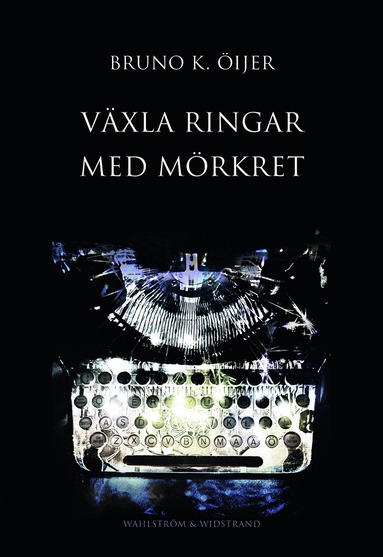

Born in 1951, Swedish poet Bruno K. Öijer has been publishing his work in his native country since the 1970s, yet to date only one of his books, The Trilogy (Action Books, 2020), is available in English translation (although as the title suggests, it comprises three books written in a series). This must change, for as humanity’s assault on the planet grows to epic proportions—waterways are poisoned, forests are felled, slaughterhouses overflow with suffering, and the climate spirals out of control—Öijer has much to say about it; his poetry confronts our exploitive relationship with nature and reveals a profound compassion for life. In this essay I will discuss Öijer’s two most recent collections published in Sweden, 2014’s Och natten viskade Annabel Lee (And the Night Whispered Annabel Lee) and 2024’s Växla ringar med mörkret (Exchange Rings with the Darkness); the translations of quoted passages are my own.

Born in 1951, Swedish poet Bruno K. Öijer has been publishing his work in his native country since the 1970s, yet to date only one of his books, The Trilogy (Action Books, 2020), is available in English translation (although as the title suggests, it comprises three books written in a series). This must change, for as humanity’s assault on the planet grows to epic proportions—waterways are poisoned, forests are felled, slaughterhouses overflow with suffering, and the climate spirals out of control—Öijer has much to say about it; his poetry confronts our exploitive relationship with nature and reveals a profound compassion for life. In this essay I will discuss Öijer’s two most recent collections published in Sweden, 2014’s Och natten viskade Annabel Lee (And the Night Whispered Annabel Lee) and 2024’s Växla ringar med mörkret (Exchange Rings with the Darkness); the translations of quoted passages are my own.

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.

Öijer cannot be called an optimist, but he does offer hope that humanity’s destructive advance will eventually be tempered. In “Romans” (“Romance”), clouds (some of which may be traces of air traffic and other sources of human overconsumption) are white wounds in the sky—yet somewhere the sky is not disfigured in this way, and “the roads must first / ask the forest for permission.” In our world, of course, other rules apply. Trees are seen not as living ecosystems but as raw materials; in “Sången”(“The Song”) the landscape is enveloped “in a melancholy, lamenting song” when a spruce is felled, and in “Asfalterade hjärtan” (“Paved Hearts”), the poet highlights the contrast between “the scent of autumn leaves” and the “piercing, unbearable sound” that has replaced it as people methodically saw down everything beautiful.