How Philosophy Can Help Us Fight for Social Justice

Arianne Shahvisi

Penguin Books ($20)

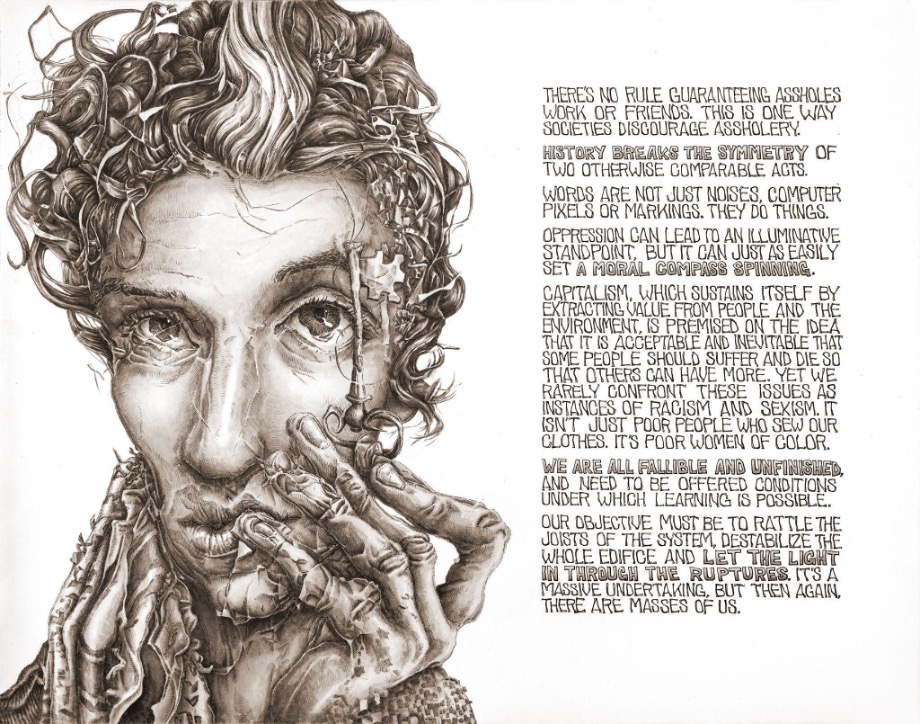

Arianne Shahvisi is a Kurdish British professor of philosophy, and many of the essays in her new book Arguing For a Better World began as reflections on questions from her students. With extraordinary curiosity and conversational ease, she lays out her arguments in response. Shahvisi is not aiming to be objective or apolitical here: “I have tried to make my reasoning clear enough that those who disagree with me will at least see where we part ways.”

Early chapters like “Can You Be Racist to a White Person?” arrive where any progressive writer would, but with a noteworthy eloquence: “History breaks the symmetry between two otherwise comparable acts.” From there, the ethical inspections grow in complexity. In “Is It Sexist to Say ‘Men Are Trash?’” Shahvisi’s response is “When someone says ‘men are trash’ they connect sexual harassment to masculinity. That’s not an act of hate, it’s an act of illumination.” She takes the torch to the very concept of masculinity when she writes, “Toxic masculinity also implies the existence of a ‘healthy’ masculinity, when such a thing seems unlikely or even contradictory. Gender is itself a system of division and hierarchy. Finding ways to make it more palatable misses the deeper moral issues.”

Shahvisi layers a lot of historical research into her arguments. In a chapter about cancel culture, she makes a pit stop in the ancient city state of Athens, where every winter, residents could write the name of someone who’d caused offense onto a broken piece of clay pot. These shards were tallied, and the most disliked person was exiled for ten years. History shows us that even early forms of canceling were not about censorship, but rather “a powerful tool for discouraging assholery.”

The intersection of the personal and political is Shahvisi’s wheelhouse, and she engages it from an array of unlikely angles. In a chapter about individual responsibility within unjust systems, Shahvisi starts with a passage from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath about banks being monsters that men made but can’t control. She funnels that into a story about backyard bickering with her father over disposable plastic, and then pivots to U.K. medical devices produced using child labor in Pakistan. It’s all over the map (as issues related to globalization tend to be), but, like any skillful storyteller, Shahvisi is setting the stage.

When it comes to discussing environmental responsibility, the professor serves up Kant’s Categorical Imperative on the world’s dinner plate. Currently, about half the world’s land mass is used for agriculture. If the rest of the world ate like the average person from India, agriculture would only take up 22%. For the average U.K. resident’s diet, we’d need 95%. For the rest of the world to eat like an American—273 pounds of meat per year—we would need 137% of the world’s land mass for agriculture. This impossibility is the teachable moment of Kant’s universalizability principle: Americans cannot morally consume this much more than their share of the world’s resources.

Shahvisi is critical of capitalist solutions to global woes. When the market sees our desire for eco-friendly options, it cashes in with a retail markup; this sells a clear conscience to those who can afford it while pricing out the masses, functionally sidelining any meaningful solution. She eviscerates the hemming and hawing we do now over our personal carbon footprints, tracing it back to the oil company BP paying the ad agency Ogilvy & Mather to market the idea that individuals (rather than fossil fuel companies) should determine their own climate impact. When fossil fuel websites promote consumer carbon calculators, our society is simply gamifying a Choose Your Own Carbon Dystopia. It’s an update to the playbook that the plastics industry used decades ago to promote flimsy recycling programs as a way of shifting the cost and blame for environmental consequences onto consumers.

The author is pragmatic about how far individual responsibility will take us. Avoiding plastic grocery bags and straws is not going to save the planet: “A single drinking straw is, in fact, a literal drop in the ocean compared with, say, the 705,000 tons of plastic dumped in the sea every year by the fishing industry.” Global dilemmas require international government coordination. Shahvisi holds room for individual impact, but Arguing for a Better World illustrates that our choices are constrained by economic forces and our desires are manipulated by advertising, all without any sense of consequence.

Shahvisi does suggest some novel solutions. For example, she asks, what would it look like if the same level of scrutiny we apply to cigarettes was applied to other products? In the same way that health warnings are a mandatory portion of tobacco packaging, what if we learned, for example, that this pair of shoes or that pair of jeans was produced in a sweatshop where child workers are running machines on 11-hour shifts for less than their country’s minimum wage? It’s hard to say how much justice individual consumers might achieve this way, but the success of tobacco regulation is hard to ignore.

Essays about how to be in our present-day unjust world abound, but the guidance Shahvisi offers in Arguing for a Better World is a refreshing amalgam of progressive politics and professorial pondering. She reminds us that mistakes are unavoidable, and that our moral and political arguments require as much compassion as reason. As she states, “we are all fallible and unfinished, and need to be offered conditions under which learning is possible.”

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024