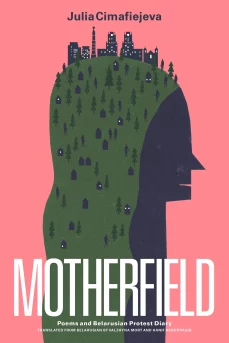

Julia Cimafiejeva

Translated by Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib

Deep Vellum ($18.95)

The first collection available in English by Belarusian poet, translator, and editor Julia Cimafiejeva, Motherfield begins with approximately thirty pages of the author’s year-long protest diary, composed in English during a mass uprising around the 2020 presidential election in Belarus; authoritarian leader Alexandr Lukashenko, in power since 1994, retained it in elections the E.U. deemed illegitimate. Cimafiejeva’s poems, translated from Belarusian by the impressive team of Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib, follow the diary, concluding with a single poem composed in English.

The diary feels written for the gaze of readers outside the events, possibly as a record in case something happens to the author. For some American readers, it will hold flashes of recognition—particularly the difficult feelings that come from continuing literary life and experiencing respites of comfort and safety during a political crisis—as well as an abundance of chilling occurrences that don’t (yet) happen here (for example, widespread internet outages as a government tactic).

Offering historical, political, and personal context to the poems that follow it, the diary is an activist’s account, but it is also a poet’s account; some of its moves and images linger and react with the poems’ more distilled elements. Of the dubious polling station where she will cast her vote, Cimafiejeva writes, “Every election day in Lukashenka’s Belarus has turned into a demonstration of the cheap and vulgar aesthetics of his power.” Her description settles on a

teenage girl in a pseudo-folk costume with a wreath on her head . . . singing about her love for the Motherland, passionately clenching a microphone. Her Russian song checks off the golden wheat fields, the big blue lakes, and the slender white storks flying over our heads. She sings that we all live safely and peacefully in our beloved Belarus.

Here Cimafiejeva shows the propagandist’s Russian-language vision of the Motherland, one that the poems will meaningfully subvert to include ecological disaster, disconnection, and stifled expression. Cimafiejeva was born in 1981 in a region of Belarus that became part of the Chernobyl zone during her childhood. Her poetry develops, often through extended metaphor, a concept of bleak, devastated embodiment with disrupted relationships between past and future, land and people, people and language.

In the opening poem, “The Stone of Fear,” the speaker’s inheritance is “a trust fund / of fear” in the form of a stone. The stone is mute and without memory, “an eternally slow-growing / embryo.” To nurse it, its inheritors must “unlearn” how to breathe, “how to say what needs to be said.” In place of nurture and natural cycles of rebirth, Cimafiejeva finds intergenerational reproduction of something wrong.

While ecological devastation, absence of language, and reproductive bodies feature in the metaphors that drive many of these poems, references to Chernobyl also appear more literally. In “Rocking the Devil,” children swing their feet at a bus stop bench; it begins to rain and the girls stick out their tongues, but no one knows the raindrops are “disastrous,” that they’ve already permeated the scene’s vibrant flora. When the bus takes the girls away, the trees wave goodbye. Similarly, “1986” is written from the perspective of a “we” who had to leave houses, crops, and graves. Strangers dismantle their homes and what remains of their lives in the ancestral village; when they come back to visit, the land does not forgive them.

If the diary operates in one register of documentary, the poems work in others, but several moments in the poems call back to the diary. “My First City, Zhlobin” portrays a steel-producing town as a body that nurtures ruin:

I fear your children, Zhlobin,

the steel-cast children

of Zhlobin

nursed by the factory’s

smoggy tits.

The speaker here, fed on the factory’s black milk, emits rust, whereas the body in Cimafiejeva’s diary observation “I feel safe inside the body of a crowd”—the body of people gathered in protest, sharing water and food and generally looking after each other—can be read as a counterpoint to the blighted bodies of the poems.

Also thought-provoking is the diary entry for October 17-18, when Cimafiejeva and her husband, a novelist, are at a literary festival launching their books. He draws a crowd, but she doesn’t. She writes, “My new poetry book was published a few days before the election. It was the worst time: no one is interested in a tiny poetry book when the main news is deaths, beatings, and detentions. But there is no other time.” This moment highlights the question of poetry’s connection to lived and recorded history, a question enacted again by the arrangement of the book itself.

That arrangement comes to a crescendo with “My European Poem,” which closes the book. It speaks to the possibility of being read by an international audience and being placed among writers working in less challenging political conditions. Of Belarusian history, Cimafiejeva writes,

When I tell it in English,

I want to pretend that I am you,

That I don’t have that painful experience

Of constant protesting and constant failing,

That nasty feeling of frustration and dismay.

In the end the speaker keeps a “beaten hope” that “builds its nest / On my roof and sings / In Belarusian.” This poem, unlike others, is dated: August 5, 2020, just before the election, before the crackdown, before the president remained, again, in power. The beginning is at the end, enacting the cyclical nature of the “beaten hope” the poem names.

Yet if Motherfield’s final poem relies on the protest diary for context, the poems that precede it—their images of wordlessness, thwarted regeneration, and ecological catastrophe—give the book its depth, and announce Julia Cimafiejeva as a poet that English language readers will want to follow in the future.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023