Jean Giono

Translated by Paul Eprile

Archipelago Books ($18)

Long before dictating the eight chapters of Fragments of a Paradise, Jean Giono spent three years translating Herman Melville’s Moby Dick; during World War II, he pursued this nautical theme with an homage to its author, Pour saluer Melville (“To Greet Melville”), published in 1941. Later, almost five years into the Nazi occupation of France and having been under suspicion of pre-war pacifism and wartime collaborationism, Giono conceived a Moby Dick à la française, turning Ahab’s anger into a scientific expedition to the South Atlantic in a surreal blend of science and poetry. These circumstances call for reading Fragments of a Paradise as both a literary feat and a testament.

Critics have seen the novel as a divide in Giono’s work, a shift away from the tragedy of the world that defined his earlier works. In Fragments of a Paradise, the main topic is no longer man’s confrontation with nature but his enchantment with it. Depending on one’s education or social status, the gateway to enchantment can be a child’s innocence, a scientist’s reasoned understanding, or the delightedly fearful awe of past legends. Officer Larreguy, a graduate of the prestigious engineering school Centrale, has an awakening that relies on all three when on a visit home he notices an unusually large ox footprint that reminds him of the winged bulls guarding the gates of the city of Nineveh he had learned about during history classes.

This quixotic quest for Arcadia leads the ship’s captain to the most remote island on earth, Tristan da Cunha, after struggling through angry seas and skies with pre-industrial tools (the only radio on board remains unused, and the sailing vessel is a three-mast corvette). This unmooring process, says Giono at the end of the book, is the only way to fight the dulling of one’s senses from the pettiness and boredom of a routine in which the deadly tanks and airplanes of war have replaced nature’s wonders. Fighting “the most terrifying thing a man can imagine: to be inanimate,” the book concludes, “This is why all the men on the ship are hastening to find a soul within themselves.”

The ship’s quest, however, remains unfinished. Michael Wood, in his pertinent introduction, lists critical interpretations but does not address whether Fragments of a Paradise should be considered a finished work. The open-ended status of the novel is in character with its focus on the dualities of life/death, good/evil, creation/destruction, and nature/civilization. Giono hinted at revisions, calling the eight chapters a “future poem”—perhaps emulating his friend C. F. Ramuz, who wrote “poetic novels.” On the other hand, Giono typically wrote quickly, and rarely made any corrections to his texts.

An armchair traveler who lived most of his life in a small town in southeastern France, Giono had an encyclopedic book knowledge of geography and foreign cultures. Interestingly, he does not list these disciplines among the expertises possessed by his fictional crew: “Zoology, Botany, Geology, Paleontology, Bacteriology, Hydrography, Oceanography, Meteorology, planetary Magnetism, atmospheric Electricity, and Gravity.” In the fourth and fifth chapters, the reader is served a heavy dose of what critics call “borrowed information” in the vein of Jules Verne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Joseph Conrad—or for that matter, Giono’s own readings of the complete works of 18th-century naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who was a founder of the theory of ecological succession, and Jules Dumont d’Urville’s multi-volume Voyage de la corvette l’Astrolabe, published serially from 1830-1833. Giono also drops clues about his knowledge of current sea exploration; expeditions to the island of Tristan da Cunha in the 1920s and ’30s made the island popular, and the sporadic discovery of Antarctic islands in the 1930s by French expeditions perhaps explains Giono’s captain’s choice of a reconnaissance area between the 66th parallel and the Tropic of Cancer.

The novel’s structure is supported by Giono’s use of both poetic and scientific language, with shifts between scientific prose, nautical jargon, rank-and-file sailors’ idioms, and dialogues replete with vieille France formulas of politeness. The first three chapters are pure poetry. The Franco-Basque crew sees a giant stingray and sperm whale through the eyes of medieval writers and in the language of John Milton, so they are unable to explain the sea creatures’ extraordinary feats of light, sound, and smells. These are explained more scientifically by the captain and the ship’s officers in the following two chapters, with a profusion of details to anchor them in verisimilitude. Poetry returns when Noël Guinard, the storekeeper, climbs to the top of Tristan da Cunha, fulfilling Giono’s idea of complete solitude and preparation for death. Poetic images are scattered through the chapters; technicolor visions of monsters and sunsets and a symbiosis between land, sea, and sky unmoor the mind as surely as the motion of wind and water. Paul Eprile’s conscientious and sophisticated translation must be commended for sparingly “paring down” the original text and preserving its stylistic richness.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025

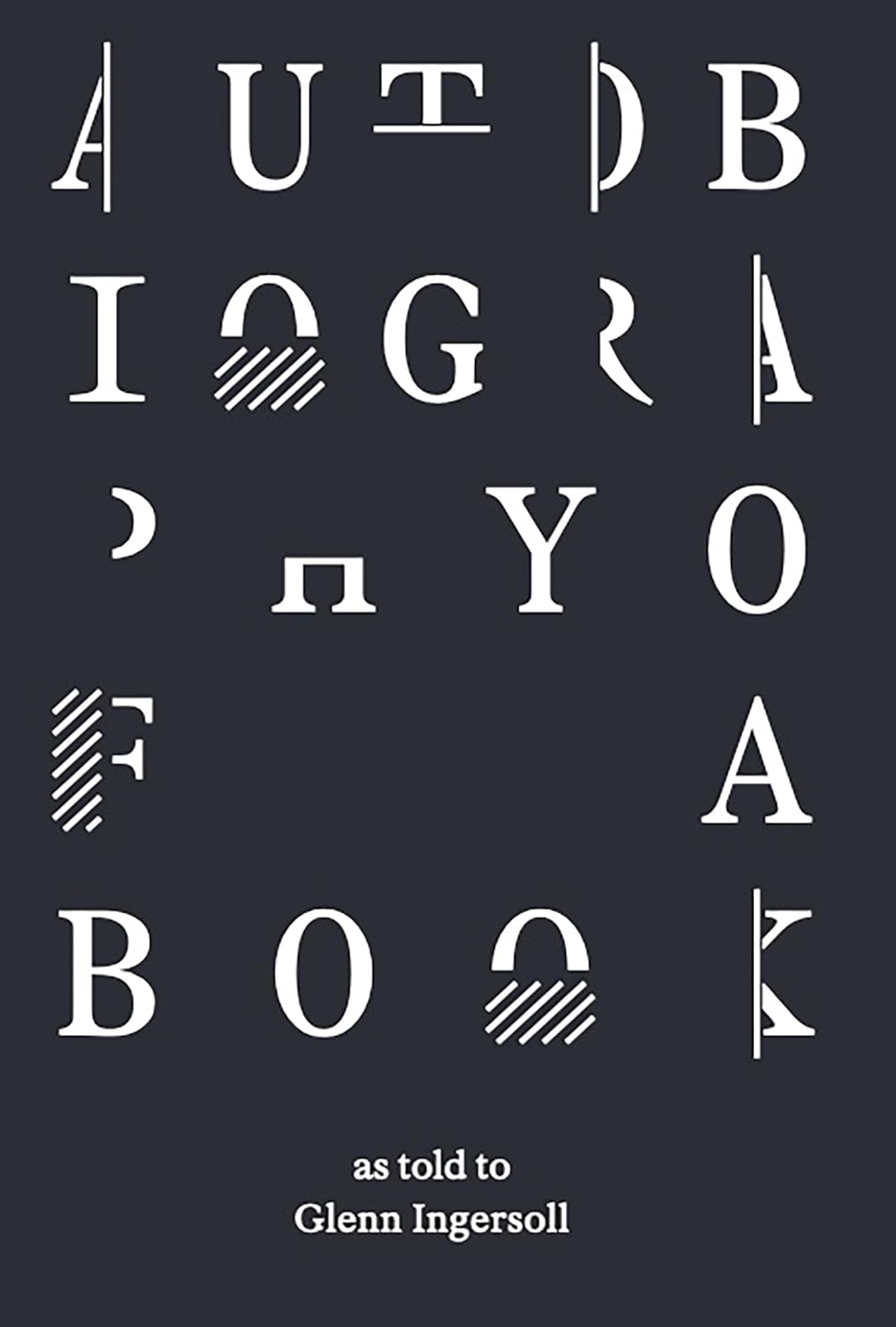

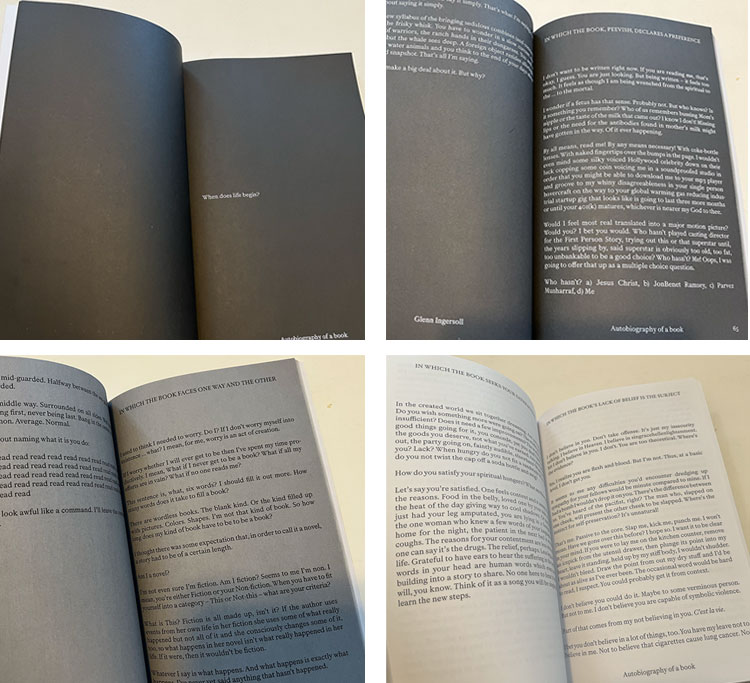

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

We march and we march some more

We march and we march some more