November 9, 2023 marked the centenary of the birth of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet James Schuyler. Schuyler, who died of complications from a stroke in 1991, wrote his poems in matchlessly clear language, not a single line or word straining for “poetic” effect. He also wrote novels and criticism with the same sharp observation and clarity.

Schuyler was born in Chicago, but his family moved to Washington D.C.; after his mother divorced his father and remarried, they moved to Maryland and then to the Buffalo area. Schuyler’s stepfather so disapproved of his voracious reading habit that he refused to let Schuyler have a library card. Schuyler attended Bethany College in West Virginia from 1941 to 1943. He left without earning a degree, and in later years claimed he spent all his time there playing bridge.

Schuyler served in the Navy from 1943 to 1947. He lived for a time on the Isle of Ischia in Italy where he worked as a secretary for W.H. Auden before moving to New York in 1950. By the mid-1950s, Schuyler was writing for Art News (taking Frank O’Hara’s position when O’Hara left in 1956) and working as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art.

Schuyler’s work in the art world introduced him to many prominent painters, including Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, and Fairfield Porter, with whom Schuyler lived from 1961 to 1972. Anne Porter once said, “Jimmy came for a visit and stayed eleven years.”[1]

Freely Espousing, Schuyler’s first major collection, was published in 1969, when he was forty-six, and includes several poems that are among his most well-known. Schuyler was an expert gardener, an adviser to his friends on plants and flowers in regard both to gardening and poetry. This interest in part shapes his poem “Salute,” where he parallels the life experiences he hoped for with a plan he’d had to gather every type of flower in a field and study them before they wilted—a plan that never came to fruition. He resists feeling regret:

Past

is past. I salute

that various field.

Equally memorable are his beautiful threnody on the death of Frank O’Hara, “Buried at Springs,” and the poem “May 24th or So,” with its often-quoted concluding lines:

Why it seems awfully far

from the green hell of August

and the winter rictus,

dashed off, like the easiest thing

Schuyler’s other major collections include The Crystal Lithium (1972), Hymn to Life (1974), The Morning of the Poem (1980), and A Few Days (1985). Schuyler also wrote novels, including Alfred and Guinevere (1958), A Nest of Ninnies, written with John Ashbery (1969), and What’s for Dinner (1978).

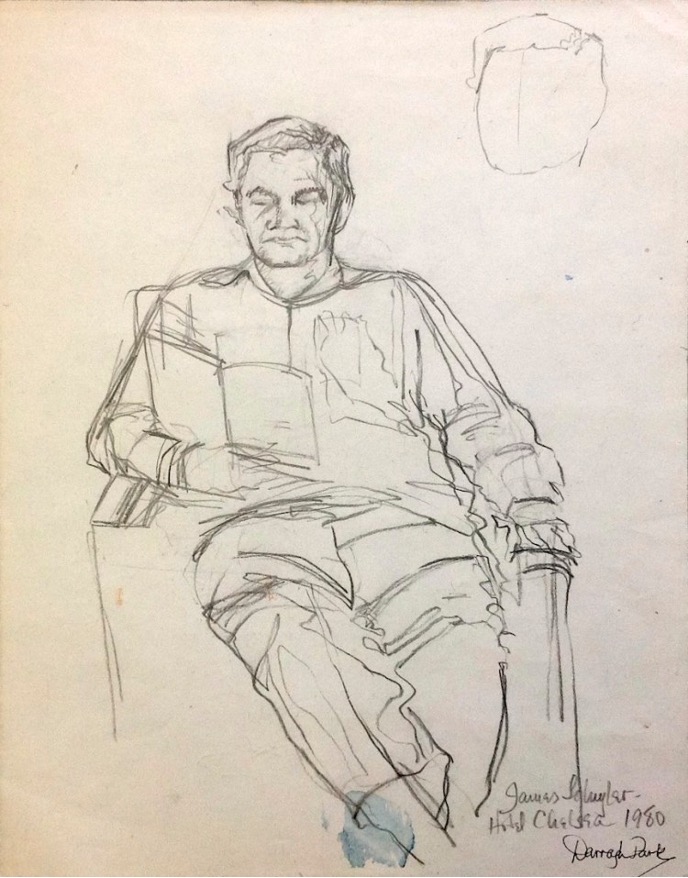

Schuyler’s poems are often autobiographical in a matter-of-fact way, and yet contemplative, with very little self-absorption or self-importance. And they are often addressed to or about his friends. The title poem of his Pulitzer Prize-winning collection The Morning of the Poem, comprising over 14,000 words, is dedicated to painter Darragh Park. Much of the poem is addressed to a “you,” but this “you” only intermittently refers to Park: “When you read this poem you will have to decide / Which of the ‘yous’ are ‘you.'” This means that even we readers who never knew Schuyler can feel he is addressing us too.

Schuyler opens the poem with other uncertainties, about the date and even about who he is: “July 8 or July 9 the eighth surely, certainly / 1976 that I know /… I being whoever I am get out of bed.” He is staying with his mother in East Aurora, New York, but his thoughts cast a wide net. He relates memories of days in New York City, of travels, of a friend playing with his whippet; Fairfield Porter appears, other poets and artists make fleeting appearances, he longs to be back home in Chelsea, listening to Ida Cox, being sketched as he reads: “I’m posing, seated / By the tall window and the Ming tree, and look / out across the Chelsea street.” He thinks about sex; he recalls his vexing struggle to stay dry in a Paris “pissoir (I mean, a vespasienne),” but the poem includes very little that could be thought of as dramatic incident.

Schuyler opens the poem with other uncertainties, about the date and even about who he is: “July 8 or July 9 the eighth surely, certainly / 1976 that I know /… I being whoever I am get out of bed.” He is staying with his mother in East Aurora, New York, but his thoughts cast a wide net. He relates memories of days in New York City, of travels, of a friend playing with his whippet; Fairfield Porter appears, other poets and artists make fleeting appearances, he longs to be back home in Chelsea, listening to Ida Cox, being sketched as he reads: “I’m posing, seated / By the tall window and the Ming tree, and look / out across the Chelsea street.” He thinks about sex; he recalls his vexing struggle to stay dry in a Paris “pissoir (I mean, a vespasienne),” but the poem includes very little that could be thought of as dramatic incident.

Schuyler suffered from depression and from manic episodes, during which he sometimes had to be restrained and hospitalized. He wrote about these experiences in his sequence “The Payne Whitney Poems,” titled after the psychiatric clinic in Manhattan. James McCourt wrote that while Schuyler “embezzled heaven,” he also “harried hell . . . the internal realm of chill and longing and dread of chaos.”[2] All the while Schuyler was struggling to right his life, he continued to write poetry, prose, and art criticism. Wayne Koestenbaum, reviewing Schuyler’s art criticism, points out how “In a review of Fairfield Porter’s paintings, Schuyler states what might be taken as his own credo: ‘Look now. It will never be more fascinating.’” [3]

Schuyler suffered from depression and from manic episodes, during which he sometimes had to be restrained and hospitalized. He wrote about these experiences in his sequence “The Payne Whitney Poems,” titled after the psychiatric clinic in Manhattan. James McCourt wrote that while Schuyler “embezzled heaven,” he also “harried hell . . . the internal realm of chill and longing and dread of chaos.”[2] All the while Schuyler was struggling to right his life, he continued to write poetry, prose, and art criticism. Wayne Koestenbaum, reviewing Schuyler’s art criticism, points out how “In a review of Fairfield Porter’s paintings, Schuyler states what might be taken as his own credo: ‘Look now. It will never be more fascinating.’” [3]

Selected Art Writings of James Schuyler was issued in 1998, The Diary of James Schuyler in 1997, both by Black Sparrow Press. These are interesting, but even more so are the two collections of his letters: Just the Thing: Selected Letters of James Schuyler 1951–1991 (Turtle Point Press, $28), edited by William Corbett and released in a revised anniversary edition this fall, and The Letters of James Schuyler to Frank O’Hara, published by Turtle Point in 2006. The letters, being addressed to someone other than himself, are livelier, juicer and more linguistically inventive than his diaristic prose.

Schuyler also wrote some diary entries specifically for a book project with Darragh Park. Schuyler had nearly stopped writing in his diary, and Park’s project proposal inspired him to begin writing diary notes again. Two Journals, published by Tibor de Nagy Editions in 1995, is a collection of jottings by Schuyler and drawings by Park done a decade earlier. The drawings are not illustrations for Schuyler’s notes, nor do Schuyler’s entries comment on the drawings. In his brief preface to the book Park explains: “James Schuyler and I decided to keep accompanying journals which would not, however, be mutually descriptive. … Much of this constituted raw material for the work of us both, often finding expression later in poems and paintings.”[4]

After the Porters informed Schuyler that he was no longer welcome to stay in their home, he moved several times, eventually settling in the Chelsea Hotel. He continued to write through the 1980s but became increasingly reclusive as he was beset with financial and health problems. Friends did their best to keep him from becoming totally isolated; Michael Lally describes a dinner at Park’s apartment, just the two of them and Schuyler, at which “Darragh and I kept up the conversation and every now and then Darragh would defer to Jimmy, giving him a chance to offer his opinion of whatever we were talking about, but Jimmy remained silent. Until it was time for me to go, when Jimmy spoke up, graciously declaring what a wonderful dinner it had been, especially the conversation.”[5] Schuyler’s friends had recognized what he was comfortable with and accepted him as he was.

After the Porters informed Schuyler that he was no longer welcome to stay in their home, he moved several times, eventually settling in the Chelsea Hotel. He continued to write through the 1980s but became increasingly reclusive as he was beset with financial and health problems. Friends did their best to keep him from becoming totally isolated; Michael Lally describes a dinner at Park’s apartment, just the two of them and Schuyler, at which “Darragh and I kept up the conversation and every now and then Darragh would defer to Jimmy, giving him a chance to offer his opinion of whatever we were talking about, but Jimmy remained silent. Until it was time for me to go, when Jimmy spoke up, graciously declaring what a wonderful dinner it had been, especially the conversation.”[5] Schuyler’s friends had recognized what he was comfortable with and accepted him as he was.

In 1977, Z Press issued The Home Book: Prose and Poems, 1951 to 1970, edited by another of Schuyler’s artist friends, Trevor Winkfield. This book gathers up two decades of fugitive pieces; after the poems, free-form prose, and quirky short plays, the book ends with “For Joe Brainard,” a long sequence of dated diary entries. The editor chooses to close on the entry for Jan 1, 1968: Here Schuyler notes the snowy weather and then warmly describes how much he is enjoying the autobiography and letters of Charles Darwin,

a man whose concerns are on the largest and most detailed scale. He often sounds so surprised that he turned out to be him. The autobiographical part has the advantage of having been written for his family—simplicity and only the reticence of intimacy. He seems to have no scores to settle whatever. I can’t think of a book with which I would rather have begun the New Year. [6]

Schuyler himself is just this sort of writer. I hope that many readers will take the centenary of his birth as a chance to discover or rediscover his extraordinary work.

[1] Douglas Crase, “A Voice Like the Day,” in Lines from London Terrace (Brooklyn: Pressed Wafer, 2017), 127-141, this quote p. 131.

[2] James McCourt, Queer Street (W.W. Norton: NY, 2004), 419.

[3] Wayne Koestenbaum, “Host With the Most” in ArtForum (March 1999), pp. 25, 29.

[4] James Schuyler and Darragh Park. Two Journals (New York: Tibor de Nagy Editions, 1995), 7.

[5] “Darragh Park R.I.P.,” Lally’s Alley, April 28, 2009. http://lallysalley.blogspot.com/2009/04/darragh-park-rip.html

[6] James Schuyler, The Home Book (Calais, VT: Z Press, 1977), 97.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023