To purchase issue #112 using Paypal, click here.

To become a member and get quarterly issues of Rain Taxi delivered to your door, click here.

INTERVIEWS

Lynn Levin: Playthings of Chaos | interviewed by Carolyne Wright

Elizabeth Metzger: In Two Separate Rooms, Breathing | interviewed by Tiffany Troy

Marty Cain: Pastoral Politics | interviewed by J. B. Stone

FEATURES

If and Only If | by Scott F. Parker

A Personal View: The Writer as Publisher | by David Stromberg

A Look Back: Bright Lights, Big City | by Neal Lipschutz

The New Life | a comic by Gary Sullivan

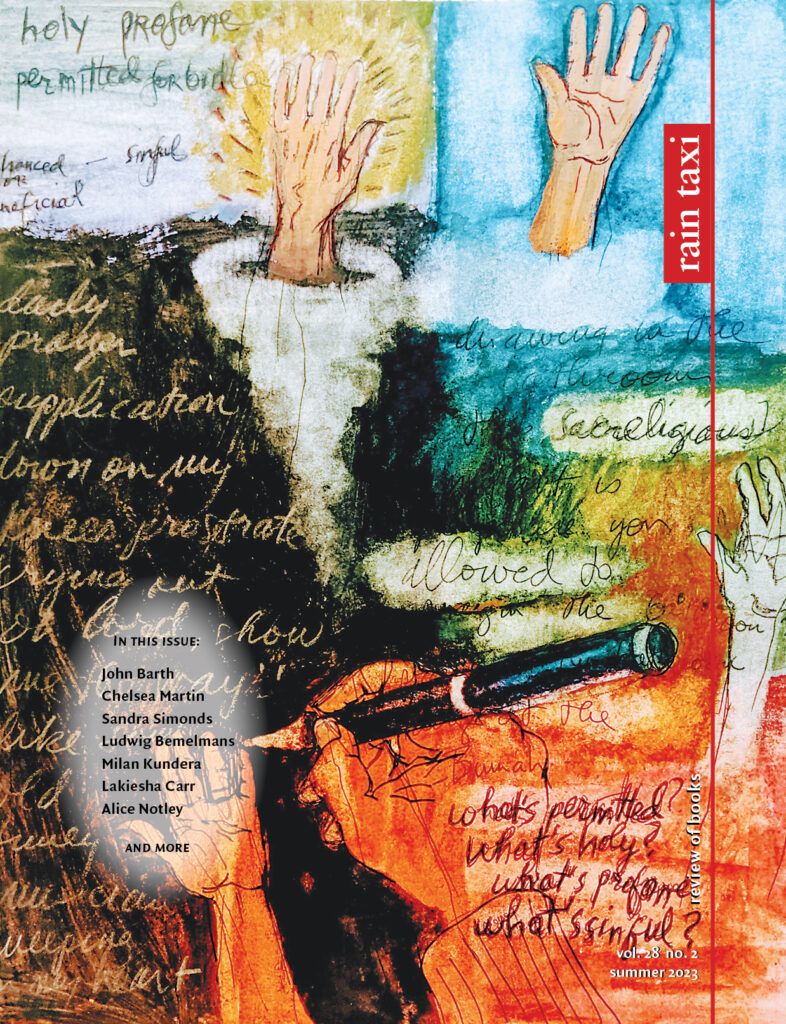

Plus cover art by John Schuerman

NONFICTION REVIEWS

Radical: A Life of My Own | Xiaolu Guo | by Nancy Seidler

Bruno Schulz: An Artist, A Murder, and the Hijacking of History | Benjamin Balint | by W. C. Bamberger

The Bible and Poetry | Michael Edwards | by Patrick James Dunagan

The Sphinx and the Milky Way: Selections from the Journals of Charles Burchfield | Charles Burchfield | by Eric Bies

Wildflower | Aurora James | by Connie Mitchell

FICTION REVIEWS

Charles Portis: Collected Works | Charles Portis | by Mark Dunbar

Notes from the Trauma Party | Michael Keen | by Alec Witthohn

The Belan Deck | Matt Bucher | by Chris Via

Maddalena and the Dark | Julia Fine | by Rachel Slotnick

Retrospective | Juan Gabriel Vásquez | by Jesse Tangen-Mills

What Falls Away | Karin Anderson | by Eleanor J. Bader

Harboring | James Sullivan | by Allan Vorda

POETRY REVIEWS

Negro Mountain | C. S. Giscombe | by Matthew Kirby

When I Reach for Your Pulse | Rushi Vyas | by Dale Cottingham

Late Epistle | Anne Myles | by AE Hines

Broken Glosa: An Alphabet Book of Post-Avant Glosa | Stephen Bett | by Joe Safdie

The Exhalation Therapist / Breathe A Wor(l)d | Patrick Lawler | by Tara Ballard

Hope as a Construction: New and Selected Poems | David Adams

| by Ellen M. Taylor

Until We Talk | Darrell Bourque and Bill Gingles | by D. O. Moore

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive | Katie Farris | by Jeffrey Careyva

Nice Nose | Buck Downs | by Simon Schuchat

MIXED GENRE REVIEWS

Poets on the Road | Maureen Owen and Barbara Henning | by Kit Robinson

Poetechnics / Poetécnicas: Designs from the New World | Yaxkin Melchy

| by kathy wu

COMICS REVIEWS

My Picture Diary | Fujiwara Maki | by Jeff Alford

To purchase issue #112 using Paypal, click here.

To become a member and get quarterly issues of Rain Taxi delivered to your door, click here.