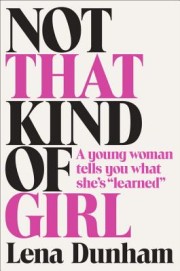

Lena Dunham

Lena Dunham

Random House ($28)

by Erin Lewenauer

Lena Dunham’s film Tiny Furniture and television show Girls registered instantly with an entire generation, confirming her as its voice. Through laughs and tears and quirks, Dunham reassures her fellow Millennials that they aren’t alone in witnessing the bizarre become familiar in recent years. She saw it too, and she managed to capture it on film. Her debut book, Not That Kind of Girl, evokes this cinematic emotion again and again as she splashes from one anecdote to the next, each just as strange and honest as one’s own reflection in the mirror.

Dunham’s memoir-in-essays displays a special kind of bravery. She gleefully flings a window open into the day’s (or often night’s) weather and lets us into her relationship with herself. You feel blood pumping through every scene and embraced by a refreshingly candid narrator, one whose chatty, articulate voice bursts with advice, information, and yes, confessions. Each chapter takes the form of a carefully crafted notebook, complete with intricate, playful illustrations of Dunham and her surroundings by Joana Avillez.

In the opening chapter, “Take My Virginity (No, Really, Take It)”, Dunham recounts being warned off sex from a memorable episode of My So-Called Life. (Here as elsewhere, Girls fans will immediately recognize details that Dunham plucked from her life and incorporated into the show’s characters.) In the following chapter, “Platonic Bed Sharing: A Great Idea (for People Who Hate Themselves)” Dunham, now in college, reflects on a boy named Jared who started it all:

He was the first thing I noticed at the New School orientation, leaning against the wall talking to a girl with a buzz cut—his anime eyes, his flared women’s jeans, his thick helmet of Prince Valiant hair. He was the first guy I’d seen in Keds, and I was moved by the confidence it took for him to wear delicate lady shoes. I was moved by his entire being. . . .

. . . . Every time I spotted him I’d think to myself, That is one hot piece of ass.

Dunham concludes the chapter with notes on who it’s ok and not ok to share a bed with; while not at all formulaic in structure nor content, this section is a microcosm of her intent to save us from her mistakes, ones that led at times to eroded self-confidence or anxiety.

Not That Kind of Girl takes a while to devour; readers will have to break often for consuming fits of laughter. Dunham describes an event at school: “The computers just show up one day . . . Everyone is buzzing, but I am immediately suspicious. What is so great about our hall being full of ugly squat robots?” At age nineteen she endures an “ill-fated evening of lovemaking” with the lone campus Republican, in which a condom winds up in the dorm room tree. She writes of another college fling, “We had slept together a few times before he ruined it all by getting into a freezing dorm shower, then hurling himself, nude, upon my unmade bed, screaming ‘I WANNA KNOW WHERE DA GOLD AT!’ (He then ruined it further by ceasing contact with me.)”

The most affecting and provocative parts of the book, however, are about her consuming romances. There was a chef (à la the chef in Tiny Furniture) who wrote cryptic emails in response to her thoughtful notes: “His were brief, and I could read both nothing and everything into them.” Their predictable yet painful break-up taught her, “The end never comes when you think it will. It’s always ten steps past the worst moment, then a weird turn to the left.” And while one’s twenties may be a time in which we want to feel like we’re getting away with something—dodging a bar tab, having casual sex, etc., Dunham shares some cautionary insights:

I thought that I was smart enough, practical enough, to separate what Joaquin said I was from what I knew I was. The way I saw it, I was fully capable of being treated with indifference that bordered on disdain while maintaining a strong sense of self-respect. I obeyed his commands, sure that I could fulfill this role while still protecting the sacred place inside of me that knew I deserved more. Different. Better.

But that isn’t how it works. When someone shows you how little you mean to them and you keep coming back for more, before you know it you start to mean less to yourself. You are not made up of compartments! You are one whole person! . . . This is so simple. But I tried so hard to make it complicated.

On a lighter, but no less complex note, Dunham shares her first encounter with her current boyfriend Jack: “Then he appeared. Gap toothed, Sculpey faced, glasses like a cartoon, so earnest I was suspicious, and so witty I was scared. I saw him standing there, yellow cardigan and hunched shoulders, and thought: Look, there is my friend.”

Dunham is a natural writer who seems to have pen in hand during every experience. She writes candidly about so much, letting us in on the process of her strong, analytical mind while discussing topics such as being raised by benevolent, feminist, “downtown rabble-rouser” parents, her hot and cold relationship with school, her gynecological conditions, how sex is damagingly depicted in movies, how she reconfigured her life after college, and “Emails I Would Send If I Were One Ounce Crazier/Angrier/Braver.”

Especially flawless descriptions distill Dunham’s experience of her liberal arts college, where she joined the staff of the alternative newspaper:

Toward the beginning of my Grape career Mike [the editor] and I dirty-danced at a party, his knee wedged deep between my legs, a fact he seemed not to remember at the next staff meeting. He ran The Grape with an iron fist, verbally abusing underlings right and left, but I passed muster and he often invited me to sit with him in the cafeteria, where he and his tiny Jewish sidekick, Goldblatt, ate plates piled high with lo mein, veggie burgers, and every kind of dry, dry cake.

But looking back she observes, “I didn’t drink in the essence of the classroom. I didn’t take legible notes or dance all night. I thought I would marry my boyfriend and grow old and sick of him. I thought I would keep my friends, and we’d make different, new memories. None of that happened. Better things happened. Then why I am I so sad?”

So much of a woman’s life is about timing, and Dunham captures the moment. We thank her for living “in a world that is almost compulsively free of secrets.” For gravitating back, always, toward “making things.” For the kind reminder not to strive for normalcy, or weirdness, or anything aside from an exploration of selfhood and a commitment to empathy. For tackling the hardest task, telling one’s own stories honestly. For the knowledge that she will continue to comfort and surprise us.

February 8, 2015, Saint Paul

February 8, 2015, Saint Paul