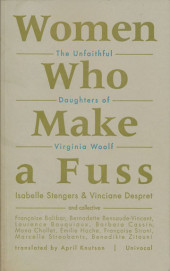

Isabelle Stengers and Vinciane Despret

translated by April Knutson

Univocal ($24.95)

by Kelsey Irving Beson

Women Who Make a Fuss: The Unfaithful Daughters of Virginia Woolf could be described as a “difficult” work, as problematic as that term is. The book, which takes its premise from Three Guineas, Woolf’s 1938 treatise on academia and the feminine, is a response to and an extension of the latter’s imperative: “Think we must.” Although Woolf pondered gender and philosophy over three-quarters of a century ago, her essay provides a solid framework for a timely exploration of modern issues such as identity politics, assimilation, and the role of a liberal arts education. In addition to discussing their own experience as women philosophers, authors Isabelle Stengers and Vinciane Despret also incorporate the responses of several female scientists, historians, and academics “on the subject of what ‘women do to thought,’” giving Women Who Make a Fuss the feel of a varied and occasionally contradictory dialectic rather than a cohesive, explanatory essay.

Although Women Who Make a Fuss is overflowing with complicated ideas, Stengers and Despret take a radically non-didactic approach—they don’t profess to know what the answers are or even what questions to ask; rather, the book is about why and how to formulate those questions. Rather than drawing any fixed resolution, the authors advocate for a constant reworking in which answers (and their questions) are precarious, ever-changing, and marked by “permeability.” Moreover, they assert that any fixed verdict would be antithetical to the project: “here is the material, it’s up to you to see . . . if you can make it compatible with your questions.” It’s crucial to keep “the space of hesitation open”—as one contributor puts it: “I cannot foresee what [the reader] will be able to do with my text and therefore I must leave room for unforeseen connections.” This epistemological strategy is incompatible with many prevailing conceptions of knowledge, such as the traditional masculine model of academic self-determination (“one exists because one crosses swords”) or the newer, neoliberal-tinged, “competencies”-based incarnation of the university. Consequently, readers that visit this book looking for pat answers—or even questions that could possibly give rise to them—are bound to be dissatisfied.

Although they discourage the reader from static conclusions, the authors are far from wishy-washy—their position may have relativist overtones, but it’s an almost aggressively interrogative relativism. Most controversially, many of the contributors are unflinching in their assertion that academia continues to demean women’s work. Nourished by both “anger and laughter,” they drop scathing feminist bon mots worthy of Andrea Dworkin (“good female students . . . know they are tolerated as long as they remain inoffensive”). Stengers and Despret confirm that the hierarchical academy may be right in its longstanding paranoia, that it was “perhaps not wrong to mistrust women, these traitors, incapable of taking seriously the great problems that transform thought into a battlefield.”

This acknowledgement of the continuing marginalization of women as a class is satisfying, perhaps even more so because of the lack of a prescription (or, for that matter, proscription) for what to do about it. In the context of rampant “polemicists (who think that the world is waiting only for their argument)” and a left that has identified itself into infinitesimal, ineffectual factions, Women Who Make a Fuss feels both old-school and innovative. Stengers and Despret implore us to reject post-feminism, with its “abstraction of an amnesiac equality,” in favor of an ever-ripening philosophy: “feminism, this adventure which must be again and again reprised anew.”