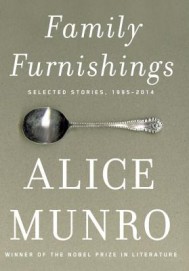

Alice Munro

Alice Munro

Alfred A. Knopf ($30)

by Keith Abbott

Alice Munro’s fiction mostly takes place in Canadian towns rather than cities, and mostly between 1930 through 1960. Suburbs with their feeder freeways rarely show up or lead to metropolitan lives. Trains feature prominently, but often their stations have been removed to make room for bus stops and benches. Few of Munro’s characters achieve higher positions than the middle class. When she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2013, reviewers scrambled to describe why such characters, subjects, and settings attracted such a large following. That answer may be found in Munro’s Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014, which provides 600 pages of reasons.

The first story here, Munro’s classic “The Love of a Good Woman,” perfectly displays how her work requires time, curiosity, and a good memory. Munro begins: “For the last couple of decades, there has been a museum in Walley, dedicated to preserving photos and butter churns and horse harnesses.” This brisk list of such rural curiosities and local items ends when her catalog zeroes in on a red toolbox that belonged to a town’s optometrist who drowned in 1951. Its label records a brief fact of the incident and an attribution to an “anonymous donor”; an assiduous list features the doc’s instruments and ends: “Everything is black, but that is only paint. In some places . . . the paint has disappeared and you can see a patch of shiny silver metal.” What readers might discover lurking in Munro’s homey litany is that when “the anonymous donor” handed over this toolbox, what was probably reflected in that silver patch was a killer’s face.

Such delayed narrative landmines are Munro’s specialty. In her excellent introduction to this edition, Jane Smiley writes that this particular story “is, in fact, a murder mystery transformed into an everyday event, and therefore much more interesting, since the actions and motives of the characters remain unknown to some and consciously hidden by others.”

Munro plies her formidable talents for stage-managing her characters’ public and private lives through happenstance and memories. Their points of view contain unexpected reveries that seem to supply reasonable influences on her characters’ reactions. But toxic surprises may burrow into another related backstory even as that character is clueless of what those details meant for them.

In “The Love of a Good Woman,” Enid, a nurse for the querulous, vindictive senior Mrs. Quinn, overhears multiple crimes but cannot bring herself to act due to conflicting impulses. The reader grows more and more alarmed for her safety, but she senses that “The different possibility was coming closer to her, and all she needed to do was to keep quiet and let it come . . . what benefits could bloom. For others, and for herself.” And readers share that hope.

In most of Munro’s stories, women outnumber the male characters; only a few in this collection are told from a masculine point of view. In her more overtly dramatic plots, the young women are curious and naïve about life outside of their family, social class, and expectations. Unsure as they are about their own prospects and lacking role models, they survey the known outcomes any locals have arranged. Flight from stultifying conditions serves as a common choice for her characters. Such stories are usually powered by getaway marriages.

In “Runaway,” one of Munro’s most riveting and modern stories, a teenage bride, Carla, provides the central point of view. Her husband, Clark, runs an isolated and financially iffy riding stable in a rural province. Carla feels alienated and miserable—her new husband could be a model for a list of a sociopath’s entitlements and resentments. She eventually attempts a solo escape by bus to a safe house in Toronto, only to panic and return to Clark. Munro’s label of “Canadian Gothic” is well earned—if you’ve viewed enough Gothic novel covers, you will know that they often feature a woman fleeing a house.

What is fascinating about Munro’s works are their careful themes and variations on life’s options. For example, in “Post and Beam,” after the main character arrives at a resigned insight, she thinks: “It was a long time ago that this happened . . . When she was twenty-four years old, and new to bargaining.” For many readers, that particular tone and message serves as a shared perception that might even touch off a burst of unruly recollections about the reader’s own losses and disappointments.

Munro’s ability to write with a clean forensic agility shines best when her characters perform unappetizing and even appalling actions. Cruelty erupts from unlikely people inside bucolic, prosaic, and hincty moments. The playwright María Irene Fornés once remarked, “You have to be an angel on your characters’ shoulder. They can be brutal, mean, but not more malicious than they are. Good, kind, but not more wholesome, more sympathetic than their limits can allow.” Munro does that.

Readers may recognize patterns for how people regard and review their past when they have either employed or mismanaged their talents during changing circumstances. Weaknesses and strengths, flawed and good choices, insights and blind spots that function in someone’s life can undergo a metamorphosis when unforeseen characters, settings, or forces engage new situations. Sometimes, survival instinct may mix with a misplaced benevolence in order to achieve the best outcome. It may also provide a snarky solution, one that stings once and leaves no cause for any further judgment. Munro’s ingredients are due to her tender, precise, and delightfully illicit touch about people’s beliefs while events are going haywire, when an ingrained or even disreputable comportment produces something noteworthy or courageous for that particular moment or need.

“The Bear Came Over The Mountain” is an example of this pattern. This gem features not one mutation of proper ethical principles, but many. The heroine is Fiona, the eccentric daughter of an illustrious, wealthy cardiologist who hosts parties in his big house. She’s a catch, but also has a very contrary and sharp personality. She lists among her suitors “a curly-haired, gloomy-looking foreigner,” “two or three quite respectable and uneasy young interns,” and assorted international visitors. Fiona grows up privileged, with “her own little car and a pile of cashmere sweaters” and maintains a belief that politics and sororities are “a joke to her.” On a windswept beach she proposes to Grant, an unimposing, unpretentious student from a local town. She does it by shouting “Do you think it would be fun if we got married?” He says yes to Fiona because it’s his belief that “She had the spark of life.”

Later, we are shown a much older Grant who is about to drive Fiona to retirement home due to her mounting amnesia. He mulls over her changes of attitude and appearance and then realizes that her hair went from pale blond to white somehow without Grant’s noticing exactly when. His alarms about her recent ominous blackout episodes float into a hope that the retirement home might be “as something that need not be permanent . . . A rest cure.” Because Grant passively waits for someone else to solve any situation, the rest home does the job: Fiona is not allowed to have any visitors for the first thirty days, cutting Grant out of her life.

Back at Fiona’s comfy family home, Grant indulges in reveries about his past choices, what Fiona might be doing now, and her new beau at the rest home. Grant eventually calls the nurse, who only says Fiona is “coming out of her shell” and hangs up. Grant is puzzled: “What shell was that?” Such a remark recalls Munro’s ability to evoke in one sentence a lifetime of someone’s lapses and deficits that may mask a startling sensibility. Grant doesn’t recall decades of how their life together has gone: his disposition is for gliding ahead with minimum bother with the past. However, during the story’s finale, Munro shows that Fiona was right to choose Grant: “‘You could have just driven away,’ she said. ‘Just driven away without a care in the world and forsook me. Forsooken me. Forsaken.’”

Grant replies, “Not a chance.”