by Olivia Q. Pintair

When Emmeline Clein began writing her debut essay collection, Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm, she originally planned to document female hysteria. Her subjects would be fictional and non-fictional women branded with that diagnosis by a misogynistic culture that pathologizes and fetishizes the pain it produces—women hallucinating into their wallpaper, sobbing in hospital hallways, and wasting away in the folds of Y2K tabloids. Her focus shifted, though, as Clein has said in interviews, when she realized how many of the figures she was researching shared struggles with disordered eating. As Clein began “to harmonize with a ghost choir” that includes medieval anorexic saints, anonymous Tumblr users, Ottessa Moshfegh protagonists, Simone Weil, Cass Elliot, Karen Carpenter, and many of us readers, the book transformed into an attempt to frame disordered eating within the context of the systems and industries that profit from it.

Tracing the cultural and medical histories of anorexia, bulimia, binge eating disorder, and orthorexia, Dead Weight undoes several tricks of the light. Through investigative reporting, criticism, and prose, Clein reveals that disordered eating is not a solipsistic malady; rather, it is an integral weapon of a racist, classist, and misogynistic society that depends upon the age-old lie that sick and sad young women are crazy, unreliable narrators. To undo that lie’s prismatic refractions, Clein shows us how common and culturally incentivized disordered eating is. Meditating on the casual gore of modern womanhood, she excavates the cultural, economic, and political underbellies of an epidemic wrought by and for a capitalist world. The result is a manifesto against “dissociative feminism” and the “lethal culture” that Western beauty standards empower.

Across Dead Weight’s thirteen essays, Clein navigates the rabbit holes of Reddit feminism, the aughts-era Tumblr-verse, diagnostic hierarchies, the eating disorder recovery industry, modern wellness culture, Ozempic’s arrival to mass markets, and the unsettling allure of bimboism. Her voice is sharp and familiar, moored to a sense of solidarity with the people living and dying along the faultlines she documents. In most autobiographical accounts of eating disorders, Clein writes, “the only way to survive seems to be renouncing your suffering sisters . . . I’m trying to find out what might happen if we blame someone other than each other and ourselves for a change.”

Clein quickly dispels any expectations for the nostalgic and bone-laden accounts of eating disorders that readers may be used to. Instead, she recasts the often isolating struggle as a collective one. In one essay, Clein explores how phases of capitalism mirror disordered eating patterns:

If bulimia was the eating disorder of Reaganomics and millennial girlbossery, and anorexia was the eating disorder of aughts-era austerity, [injectable weight loss] drugs might foster an eating disorder for a new age of technocapitalism, wherein we try to recast hunger as just another inconvenience we can eliminate with an app.

Elsewhere, Clein traces the normalization of eating disorders in a culture of ubiquitous commodification. “Eating disorders are good for capital,” reads one essay, which traces “the chain of money that leads from eating disorder treatment centers, weight loss companies, CBT companies, and pharmaceutical companies back to the same pool of investment capital.”

As Clein probes statistics and anecdotes, it becomes clear that disordered eating is not a mark of girlish insanity or vapid self-interest, but an apparatus of late capitalism. Women and femmes are peddled a beauty standard that remains a thinly veiled prerequisite for financial and social success, then are pathologized for trying to reach it. “Heroin chic is back,” The New York Post announced in 2022—Ozempic makes it easy now. As most anyone on the internet could attest, social media algorithms incentivize conformity and drain our energy to rebel. We seem to lose something when we follow their rules—and also when we don’t.

“I’m trying to be honest here: I’ve always wanted to live the kind of life that ends up in a story,” Clein writes, leveling with her audience. The women who starve themselves in books or on screen, she acknowledges, are often main characters, and maybe that is what the supposed trade-off is: Submit to the role, and you could be the heroine. But as Clein continually reminds us, those stories “are fiction,” repeated enough that they have become not only a cliché but also a narrative propping up several multi-billion-dollar industries and a conglomerate of mental illnesses with one of the highest collective death rates in the world.

For Clein, writing Dead Weight was an effort to humanize suffering people who, like the Victorian women drowning in white dresses in 19th century British and American literature, are usually romanticized in media but dismissed in real life. Like Simone Weil, Clein understands the visceral way in which the question of how or whether to eat is also a question of how or whether to be; the Self, as an experience and as an imagined ideal, is her primary interest. Early on in the book, she asks readers to picture the archetype of the “skinny, sexy, sad girl” as an ideal self that floats out at sea, “purring false promises from just over the horizon line”; she then points out that like those literary women whose misogyny-induced deaths are so predictably written as romantic inevitabilities, this archetype didn’t swim out to sea of her own accord. “Someone stranded her at the vanishing point . . .” Clein writes, “and they don’t want us to reach her because then we might save her, convince her she’s been lied to like the rest of us.”

Advancing toward the menacing clarity of that realization like a chess player, Clein refuses to talk down to her readers or underestimate their agency. She is interested in a political future beyond both the commodification of pain and the avoidance of it. “I have a question for bimbos and dissociated girls alike,” she writes in the collection’s coda. “How are we shaping our bodies and behaviors to become desirable to the most powerful, according to their value system?”

As Clein contextualizes her subject matter within existential questions about selfhood and solidarity, Dead Weight becomes relevant not only to those suffering from eating disorders, but to anyone trying to remain feeling and alive in a capitalist world that commodifies selfhood at the chaotic clip of a panopticonic auctioneer. The Self, Clein posits, is not an asset that should either escalate in perpetuity or submit to disappearance, but a synthesis of experience, alive insofar as it risks its own imagined stasis toward relationship and connection. Undermining narratives of our own isolation and insanity could destabilize industries that profit from them, Clein argues. “We don’t have to be solo heroines on lonely journeys; we can also be sisters and friends, side characters in someone else’s story . . . We can, maybe, even be the person who changes it.”

At the end of the book’s penultimate essay, Clein returns to consider the roots of her own suffering from disordered eating:

I watch my adolescent body get thrown like a pebble into a pond. The blame ripples out, past my therapist, another woman floating on her back in the water, into green fields of money and men. I see magazines filled with waifish models and . . . the Instagram ads . . . offering me mental health quizzes and meditation for women apps and Gwyneth Paltrow’s Netflix show and diet tea. I see the eating disorder memes and weight loss progress Instagram accounts and slim, smiling influencers, and wonder how I could have ended up anywhere but at the bottom of the lake.

“It can be politically mobilizing to feel the weight of that pain,” Clein said in a conversation with Rayne Fisher-Quann published in Nylon; “it makes me want to be alive in order to try to change it in what little ways I can so that maybe some younger girl doesn’t have to feel this bad.” Ultimately, Dead Weight is an offering born of Clein’s commitment to doing that—to envisioning a world in which girlhood isn’t a minefield of diet trends, where genuine human connection renders dissociation unnecessary, and where bodies are land and not property. In this world, Clein dreams, the lake might not be a place where people drown or disappear, but an expanse where we might find each other. This is a world she can see, she promises—not over a horizon line, but somewhere closer.

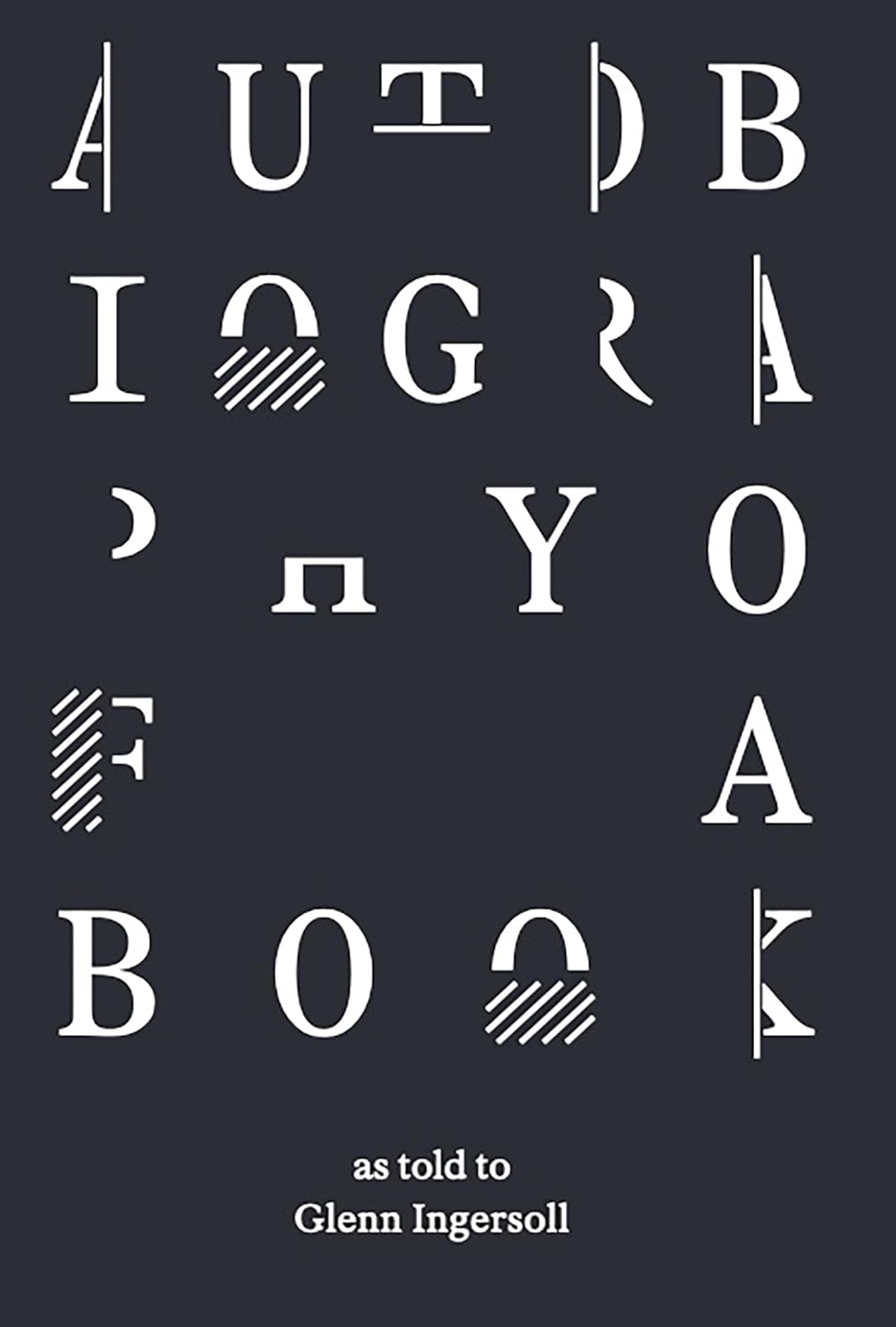

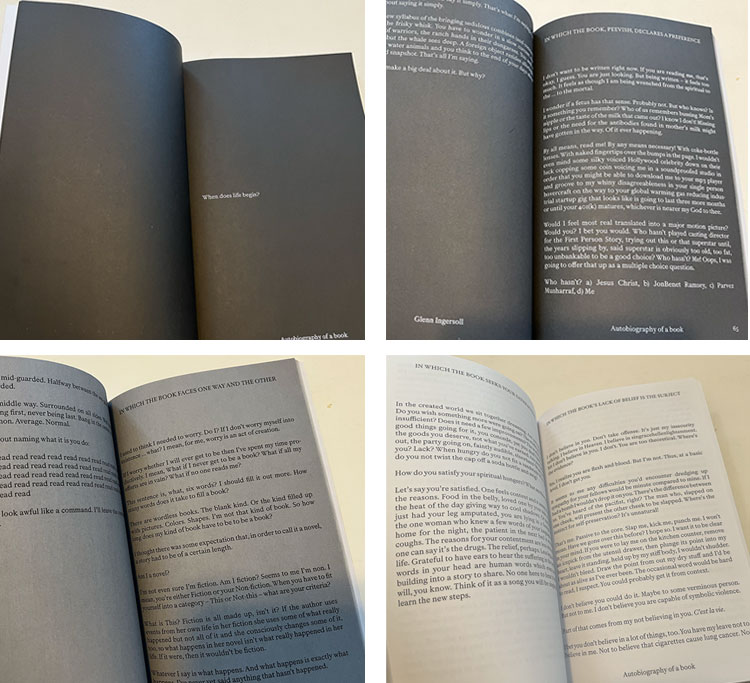

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

We march and we march some more

We march and we march some more