by Paul Buhle

So much time has passed since the brief golden age of underground comix that younger readers can be forgiven for not recognizing the word “comix” as an emblem of the late 1960s. Likewise they may not know much about the most significant American artist of the movement, Robert Crumb, who is more readily identified in France (where he has lived since 1991) than in the U.S. During the 1990s, the release of the documentary film Crumb stirred interest but also renewed old grievances. In 2009, Crumb’s masterful long form The Book of Genesis appeared, looking to many veteran fans of the cartoonist as an apotheosis (and indeed, given that the artist is now in his eighties, it is likely his final major work).

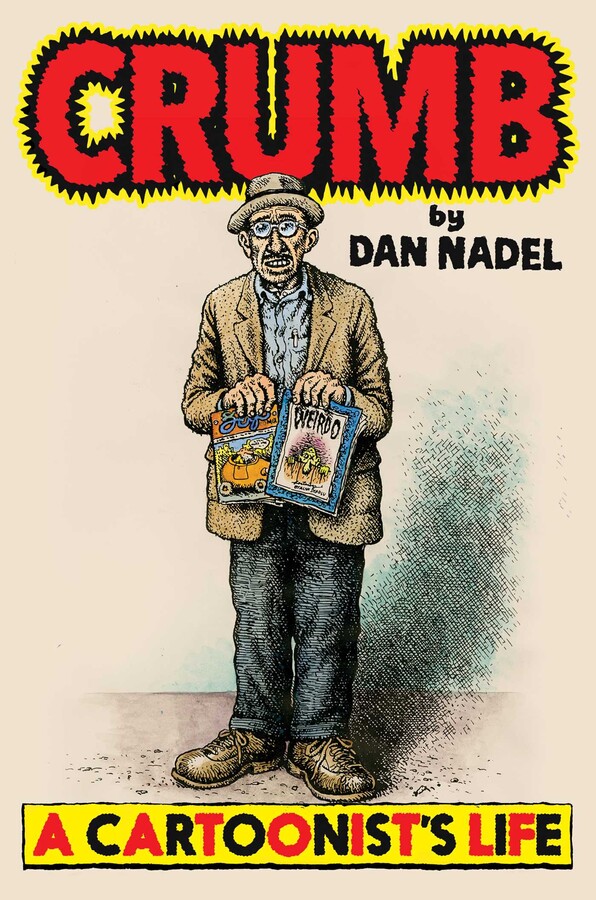

When comic historian Dan Nadel asked Crumb about writing a biography, Crumb not only agreed but made available an extensive archive, one that helps illuminate how a life journey so full of adventure can add up to something greater. The richness of detail and personal insights, including reverse-image self-insights of a near-confessional nature, in Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life offer a deeper and more nuanced view than even the artist’s most devoted fans could have guessed.

Many of us who have met Crumb, corresponded with him, or wrote about his work—my own first review of Crumb appeared in 1968—somehow lost sight of his uniqueness by the 1980s. We probably never understood a few key basics of his intentions, both artistic and personal: his dedication to music, for instance, and his anti-career ferocity in that world. Crumb learned to play several stringed instruments, and the Cheap Suit Serenaders that he formed played in California and beyond for more than a decade. He adamantly refused what other band members clearly wanted, which was to make the big time—he was escaping the big time, actually, in the way he knew best.

Crumb’s lifetime effort to deepen and improve his art offers another insight into how he is a more-than-modern artist. Imagine him in his adopted village in Southern France, abandoning larger reputation-securing works for individual pieces that would sell at a good price to collectors—very much in the mode of artists centuries ago. In that same village, he pitched into rebuilding historic houses for newly arrived friends to live in, and cleared paths to the nearby mountain so that they more resembled the same paths used by shepherds for centuries. Meanwhile he sketched away, finding for himself new details in the many ways to create.

We still have the familiar Crumb, of course, and every good reason to thank Nadel for giving us a close (and at times appropriately unforgiving) view of his world. Crumb’s family, for instance: his doomed brothers and his sister, all of whom he sometimes sought to help decades after they had left home; his father, a military veteran who slapped and insulted the boys, but ended up with a career of sorts, if never satisfactorily reconciled to his former wife and his children; his mother, divorced and daffy in old age, the strange and pathetic figure in the documentary film. In sobering ways, his family is a mirror of R. Crumb and vice-versa, but unlike his brothers in particular, he survives more or less intact. Nadel covers the mostly uncomfortable family territory assiduously and sympathetically.

Perhaps Crumb was not really, as was sometimes assumed, on the verge of suicide when he hopped on a bus from Delaware to Cleveland in the early 1960s, there finding a fast friend in another comics legend-to-be, Harvey Pekar. Perhaps he did not dive hopelessly into a bad marriage but rather stumbled into a relationship that lasted a fairly long time and only ended badly, with Dana Crumb broke as well as morbidly obese. As a good biographer should, Nadel unpeels one layer of contradiction after another. From Cleveland and a promising (if hackish) job drawing “funny” greeting cards, Crumb made his way up the artistic ladder just as the counter-culture era blossomed. LSD had a big effect on his work, especially in his recuperating of vintage vernacular images of American life earlier in the century—the budding artist indeed seemed to intuit the direction he was traveling. His comics, in mature form, still resemble the amateur efforts created with his brothers when they were kids together, crudely published and sold or given away.

Crumb moved to San Francisco in 1967 and remained in Northern California for over two decades; in Nadel’s telling, these years are full of little surprises. Amidst the dope smoking and love-ins, he and Dana deftly blend in by selling comics from a baby buggy; amidst the rush of assertive, sexually liberated women at that place and time, he also proves to be hopelessly adulterous, so much so that “adultery” does not begin to cover the subject. Still smarting from the brushoffs of his gangly puberty years, he both craves the offerings of women and feels resentful toward them; happily and also unhappily, he takes his solace and his revenge in his comic art. With the id uncensored and increasingly unleashed in his work, the world of underground comix becomes so tied up with Crumb that his comics would sell in excess of a half-million copies, ten times that of his most successful counterparts.

Attacked for good reason by up-and-coming women cartoonists creating their own feminist comix—Trina Robbins and Sharon Rudahl in the lead—Crumb lashed back at them repeatedly, sometimes first apologizing and then digging himself in further. Whether or not his desire to “ride” women with large posteriors pseudo-sexually is misogyny or not is debatable (his female defenders claim they find it sex-positive), but it is hardly any version of normality. In the ’70s, Crumb marries fellow artist, Aline Kominsky, who delivers him from much of his personal hell and into the melting pot of Jewish American culture. He does not learn Yiddish (let alone Hebrew) and feels no vibes for Israel (nor does Aline), but together they explore the contradictions of their shared life, often in humorous collaborative works; their union continues until Kominsky-Crumb’s death in 2022.

The strength of Nadel’s biography rests in no small part on an understanding of what Mad Comics and its creator Harvey Kurtzman meant to Crumb. In a 1977 interview, I asked Crumb how Kurtzman had influenced him and he responded that this is simply how art works: a young artist emulates a master although he feels it is impossible (or at least unlikely) to reach the latter’s level of genius. In the early 1950s Kurtzman and Mad Comics, assaulting Joseph McCarthy amidst the Army Hearings, ridiculed a wide spectrum of mass cultural developments as well as the cliches of mainstream comic art; Mad Magazine, the toned-down version that appeared from 1956 onward, was already something different, less intense, more appropriate for younger readers, and far less dangerous. Crumb wanted to become more dangerous, and he did: Snatch Comics, a 1968 anthology of super-pornographic stories edited by Crumb and including his work as well as that of cartooning comrades such as S. Clay Wilson and Victor Moscoso, assaulted almost every propriety, with Crumb going as far as his imagination could take him.

Weirdo, the magazine Crumb launched in the 1980s, helps mark the shift from the underground comix era to the “alternative comics” paradigm that succeeds it; it had no aim at financial success or particular artistic merit. Instead, it offered a lot of what would come to be known as outsider art, including some comics that could hardly be considered comics. His own gag pages recuperated one of the oddest features of old joke magazines, showing photographs of him engaged in a kind of 1940s pop culture ballet with women in leotards—no real violence, no real sex, yet everybody seemed to have a good time.

After the heyday of the San Francisco years, Crumb lived in Winters, California, in the woods away from the college town of Davis; there he and Aline raised a daughter and produced enough art to keep the family budget intact. Crumb’s work with the ecology-minded newspaper Winds of Change seemed to reflect his larger vision, but his splendid hatred of the rich, their luxuries, and their culture had nowhere to go in Reagan’s America. Making the move to France in 1991 was the final step in Crumb’s journey. Although Aline had the stronger impulse to live in a more beautiful and just society than consumerist USA (new housing “developments” had already grown closer to their home in Winters by 1981), it worked out perfectly for him—he finally got away from the fan-boys and fan-girls, successfully escaping as many of us might also have wished to do. It wasn’t a bad endgame for such a wild trajectory, an arc well summarized and honored in Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life.