Attending to Body and Earth in Distress

Ranae Lenor Hanson

University of Minnesota Press ($19.95)

by Elizabeth Bailey

The Danube is no longer blue, I hear as the PBS NewsHour covers the summer 2022 heatwave. Aerial shots pan along wan rivers. The voice-over catalogues the faltering crops, throttled hydroelectric power production, and impassable shipping lanes. The bridges catch my breath, their long spans straining over narrow trickles; lanky support pillars spike from exposed riverbeds dried to a pale suede. Drought makes these feats of engineering look foolishly overbuilt, even obsolete.

From the headwaters of climate change, many crises compound: economic, political, environmental, and social, but also the less newsy crisis of living in the Anthropocene. In Watershed: Attending to Body and Earth in Distress, educator and climate activist Ranae Lenor Hanson explores parallels between the lived experiences of climate change and severe illness. Adult-onset diabetes sent shock waves through Hanson’s life. With her frank account of the illness—its avoidance and disruptive diagnosis, its indignities and halting integration into daily life—she offers a personal map against which readers might chart their own ways through the uneasy waters of the climate crisis.

One parallel between bodily and planetary crises is in Hanson’s response to her escalating illness. At first, her symptoms are vague and ignorable: dizziness, fatigue, growing thirst. She copes by catching hold of a signpost at the bus stop when unsteady or perching “on the edge of a stool” when she can no longer stand up while teaching. This avoidance feels familiar: We all hope that a nagging discomfort will abate unaided, and tend to sidestep reckoning with deeper systemic issues, be they interpersonal, bodily, or environmental.

As Hanson’s symptoms worsen, diabetic ketoacidosis sends her to the hospital where she must finally acknowledge a new reality: without daily, even hourly attention to her health, she risks damaging her body, or shutting it down altogether. Later, she reflects on the difficulty of stopping to address crises; there are “exams to study for, jobs to get (or get to), children to raise,” and other duties and deadlines. After Hanson finally drags herself to an urgent care clinic, she begins to see that “like a diabetic crisis, climate trauma numbs our brains. The threat is too big to conceive, so we relegate it to the background. There it sits, unsettling everything, while most of us focus with increasing intensity on whatever task or diversion is at hand.”

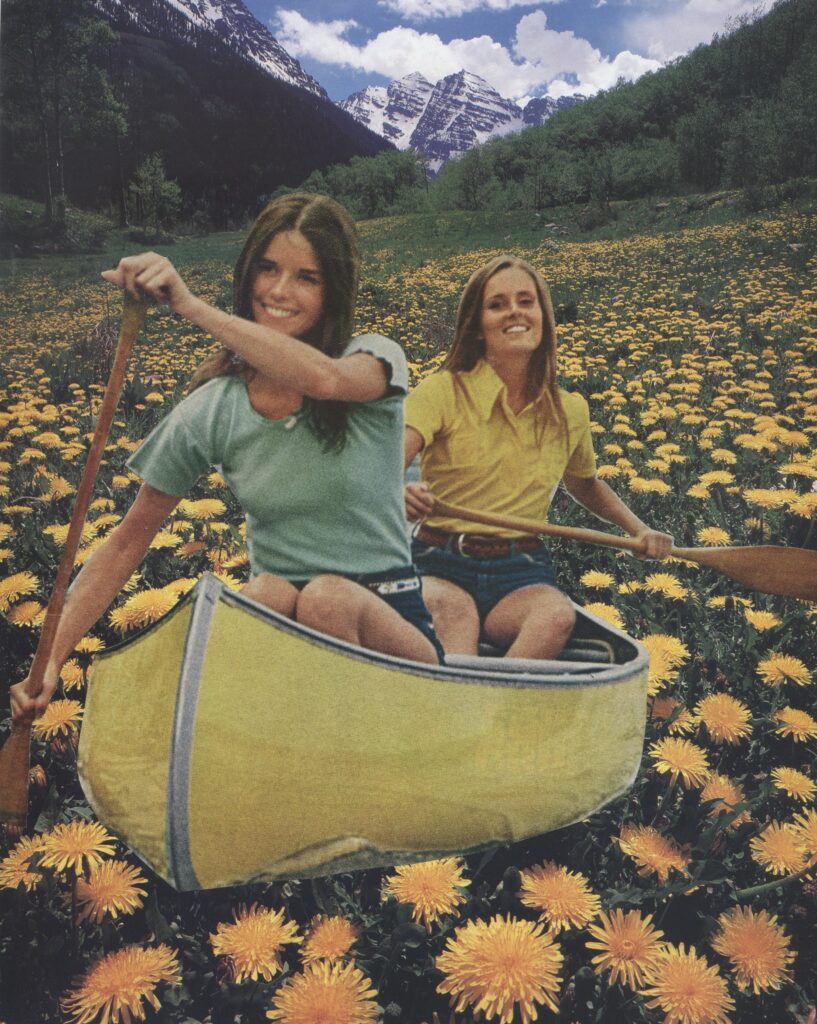

Hanson’s midlife diagnosis upset not only her daily routines, but also her sense of herself as a capable individual treading lightly on the earth. Type 1 diabetes, with its required test strips, glucose monitors, insulin pumps, doctor visits, dietitian sessions, diabetes nurse educators, and medical device hotlines, abruptly ropes Hanson to numerous systems and the “ecological and social and infrastructure stability” needed to maintain health. This new dependency puts Hanson in tension with herself. She anxiously, almost obsessively, counts the “five used and useless strips” wasted while learning to test her blood sugar. Even once she gets the hang of the glucometer, she is pained by how much more trash she generates to stay alive as a diabetic, and bemoans her lost dream “to canoe off into the woods and survive on my own.”

A lifelong Minnesotan, Hanson’s rugged mentality was nurtured by a childhood in the “loosely connected, fiercely independent, unaffiliated Christian network of the north.” Her memories of the Minnesota backwoods have a timeless quality. Seasons roll past, drying peppermint and rosehips on window screens, drilling for fresh spring water, winter camping in trappers’ cabins operated on the honor system, and enduring the casual sexism of a grandfather refusing to teach his granddaughter to drive the tractor. Against this backdrop, certain moments bring the reader swiftly to a particular era. “Though the mosquitoes were thick” when men came to spray the yard with DDT, Hanson’s mother “had read Silent Spring and ran out in protest. . . . Laughing, they sprayed anyway.”

At the hospital, the doctor returns with “good news”: If Hanson “can find a deep, cool lake and a waterproof container,” she’ll be able to store insulin and “live in the woods for up to three months.” Hanson smiles, but then her thoughts turn to climate change. “All I need to do . . . is keep my lake cool.”

As Hanson struggles to navigate the challenges of her new reality, she returns to teaching classes in ethics, global studies, and ecofeminism at a Twin Cities community college. Her students come from many countries, and some “from more than one country by way of relatives and refugee camps.” In one class, students from Africa debate Nile water politics. For them, the implications of a new dam aren’t abstract; all the places the dam will affect—where it is built, where it takes water from, where it floods, where the water is sent, where war will “surely” break out—are personal, filled with “the grandparents of someone” and “the farms of someone else.” Their discussion is not only knowledgeable but undergirded by the firsthand knowledge that “Water is truly life. Or death.”

To some, the climate crisis may feel distant, a problem to be solved for the benefit of future generations. But Hanson’s students are already living amid the concentric crises (drought, famine, fighting) of climate change. For these students, this isn’t a future crisis. Catastrophe is ongoing. Disruption and upheaval have become their own way of life.

Watershed operates on this human scale. By braiding stories of individual struggles with climate-based calamity, Hanson encourages readers to honor and attend to the personal side of a global catastrophe. And what then? Hanson offers some of her suggestions in chapter titles and section breaks: “Pause to Survey,” “Consider the Need to Stop,” “Feel the Grief,” “Bear Witness,” “Practice for Mourning.”

One phrase in particular seems capable of holding the others: “Rely on a Deep, Cool Lake.” Each of us, this phrase suggests, would do well to find a reservoir from which to draw calm and strength. Let it sustain and replenish you, and learn what you can do to replenish and sustain it.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023