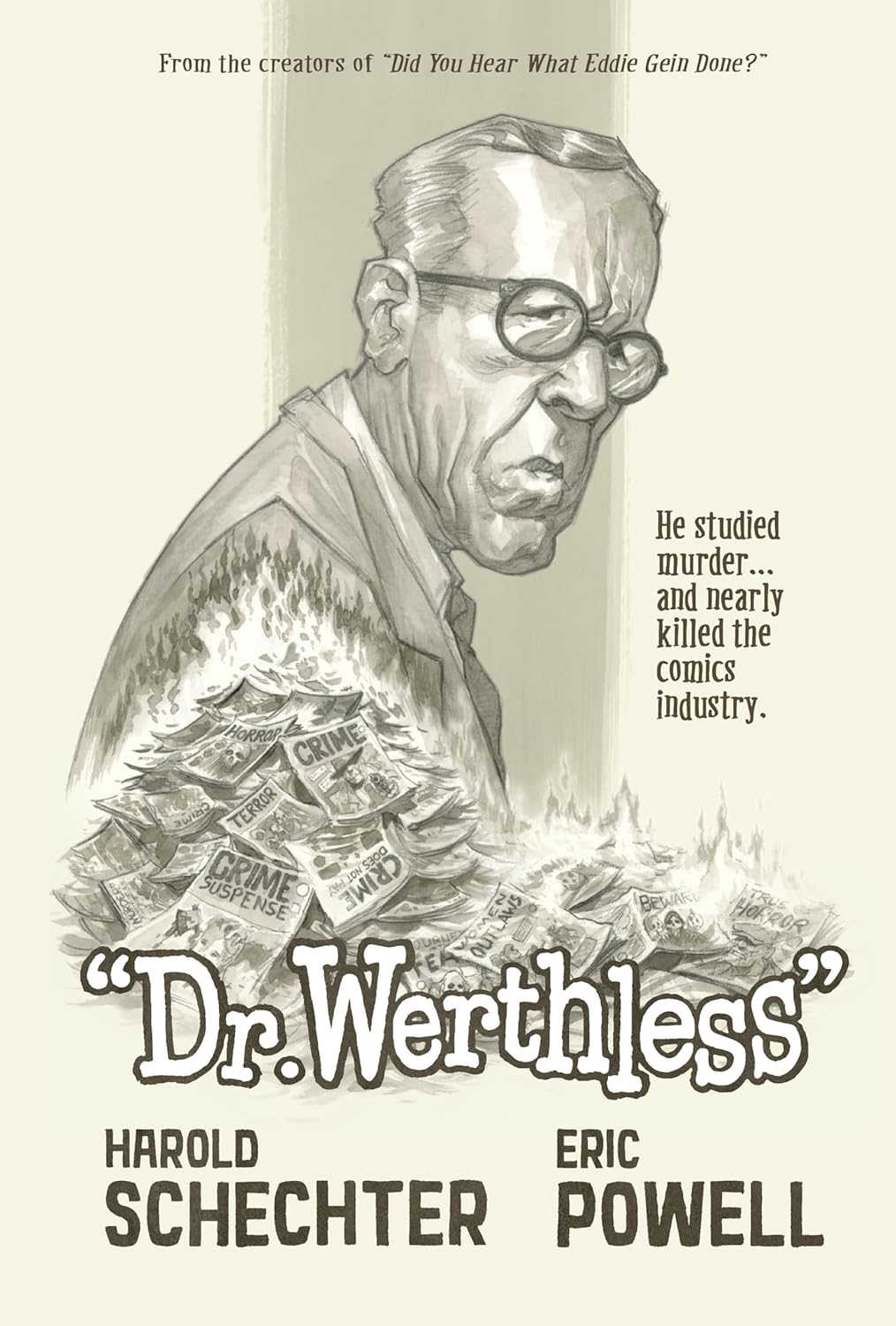

Harold Schechter and Eric Powell

Dark Horse Books ($29.99)

by Hank Kennedy

“He ruined comics”—or at least that’s the story countless books, articles, and documentaries have told about the damage Dr. Fredric Wertham did to the art form. Parent-Teacher Associations, members of the clergy, and even J. Edgar Hoover had all voiced their opposition to comics as well, but by claiming that comics caused juvenile deliquency—a claim the German-American psychiatrist made through articles in Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Review, his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, and testimony before Congress later that year—Wertham became the face of the anti-comics campaign in the United States.

Dr. Werthless, a graphic biography written by Harold Shechter and illustrated by Eric Powell, tells a more nuanced story than the one most comics fans are used to hearing—in fact, only the last quarter of the book is dedicated to crusade against the medium. Wertham had a long career before he turned his attentions to comics, so readers who know him only as a moral scold will learn much about his involvement in notorious murder trials, the Civil Rights Movement, and even the study of comics fandom.

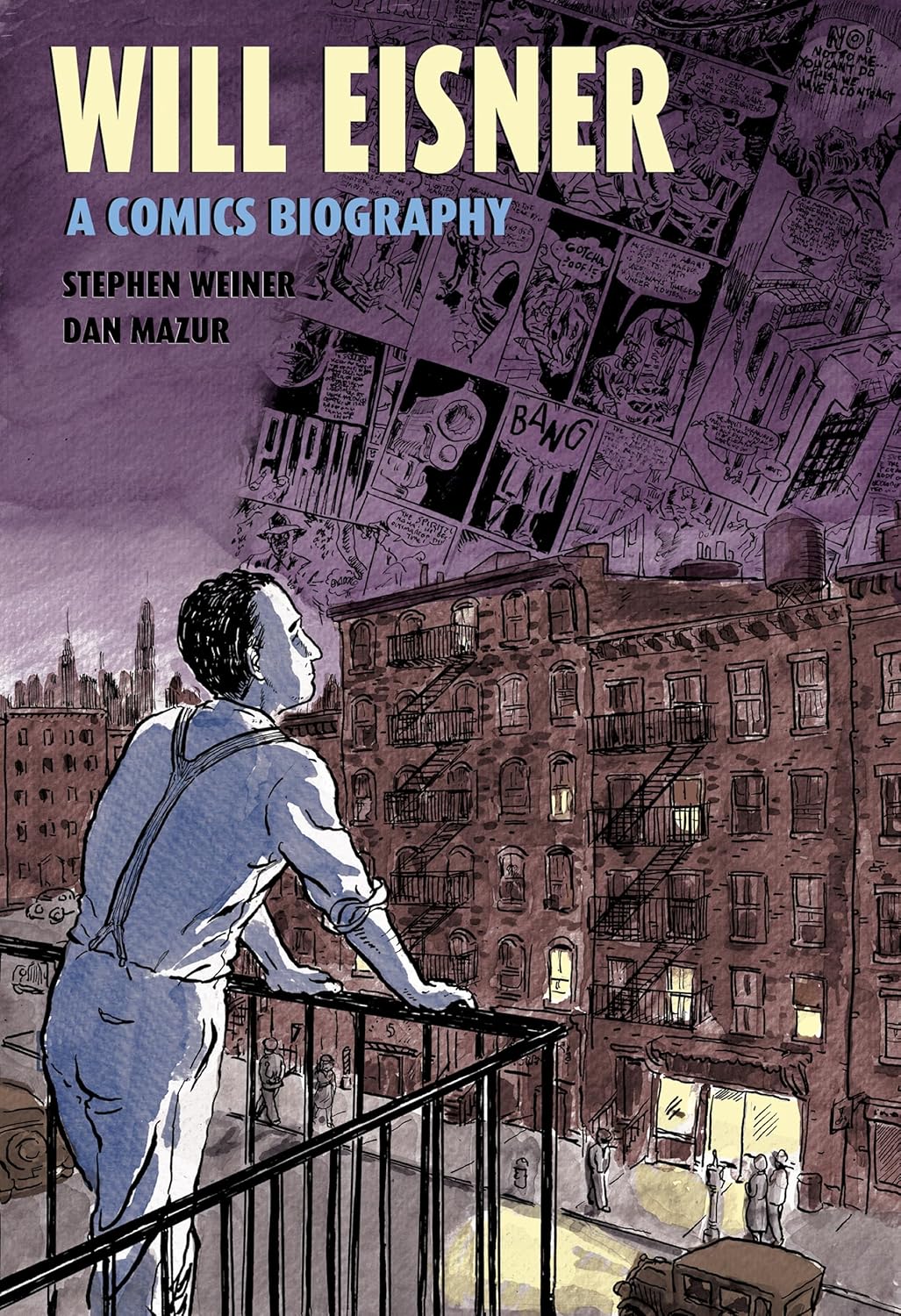

Powell’s Eisner-Award winning comic series The Goon contains a healthy amount of black comedy, but there’s little comedy of any kind to be found in this book. Constantly frustrated at the perceived slowness with which his career advanced, Wertham was as undiplomatic as he was intelligent, so other physicians found him vain and difficult to work with.

There are also no laughs in sight when Albert Fish, a notorious rapist, child molester, and serial murderer who killed at least three children, enters the story. Shechter is a renowned true crime writer (he wrote a book on the Fish case, among many others), and he avoids the genre’s most egregious pitfalls here, taking care not to glamorize the killer nor blame his victims for their own deaths. Wertham testified for the defense in Fish’s murder trial, stating that Fish was insane and needed to be studied in a mental hospital—to no avail. Due to the brutality of his crimes, the jury found Fish guilty and sentenced him to death by the electric chair.

Powell’s EC Comics-influenced style aids him in recreating the comics that so offended Wertham. His work evokes EC greats Jack Davis and “Ghastly” Graham Ingels, which serves him well when he reproduces covers and interior art from the period. And he is clever with his storytelling—for example, he conveys the tale of Wertham’s first book Dark Legend: A Study in Murder, which appeared in 1941, in Golden Age style, complete with Ben-Day dots. (Though not every similarity to the Golden Age is positive: When the book relates the role EC Comics publisher William Gaines played, the layouts begin to resemble EC’s famously text-heavy ones, forcing Powell to cram his drawings into the small amount of space left over.)

While Schechter and Powell give due space to Wertham’s history beyond his attack on comics—he opened and ran a low-cost clinic in Harlem to treat Black children, for example—they unfortunately omit what doesn’t fit their thematic glue. In one chapter, they dramatize a letter to Wertham from a gay barber who asks for help with his “condition”; the doctor responds sympathetically, leading readers to think Wertham to be tolerant, even ahead of his time, in his treatment of gay people. The truth is altogether different: Seduction of the Innocent reveals that Wertham viewed homosexuality as a social contagion children must be protected from; he somewhat famously opined that Batman and Robin were “the wish dream of two homosexuals living together” and Wonder Woman was “the lesbian counterpart of Batman” whose “strength” made her “unwomanly.” Shechter and Powell excise this context, but given the large amount of research they did (there’s an extensive bibliography in the back of the book), it seems unlikely that they weren’t aware of Wertham’s true stance.

Wertham’s sin, to the authors of Dr. Werthless, is to have believed in the possibility of improving human behavior. They place Wertham in a category of those who “deny that we are natural-born killers” and instead think “murderers are the products of harmful social influences they are exposed to as children. They believe if young people could only be shielded from violence in media, juvenile crime would cease to exist.” But doesn’t this draw the contrast too starkly? Are our only choices to censor violence in media or to believe in a historically determined, unchanging, inherently violent human nature?

Wertham’s sin, to the authors of Dr. Werthless, is to have believed in the possibility of improving human behavior. They place Wertham in a category of those who “deny that we are natural-born killers” and instead think “murderers are the products of harmful social influences they are exposed to as children. They believe if young people could only be shielded from violence in media, juvenile crime would cease to exist.” But doesn’t this draw the contrast too starkly? Are our only choices to censor violence in media or to believe in a historically determined, unchanging, inherently violent human nature?

Shechter and Powell would hardly be alone in this pessimistic and arguably conservative view of humanity. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins wrote of “the selfish gene”; to zoologist Desmond Morris, humanity is nothing more than a “naked ape.” Yet this is not as settled as the above would have it. Canadian anthropologist Richard Lee, a winner of the Anisfeld-Wolf Book Award, has written that primitive humans were marked by a “generalized reciprocity in the division of food” and “relatively egalitarian political relations.” Clearly, human nature, such as it is, is fluid.

Wertham’s greatest fault was not to believe in improving the human condition—rather, it was that he wasted so much of his life on the blind alley of censorship. It was this that so diminished his professional legacy, turning a respected doctor with good intentions into the “Dr. Werthless” comics fans mock today.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2026 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2026