Anna Funder

Knopf ($32)

by C.T. Wolf

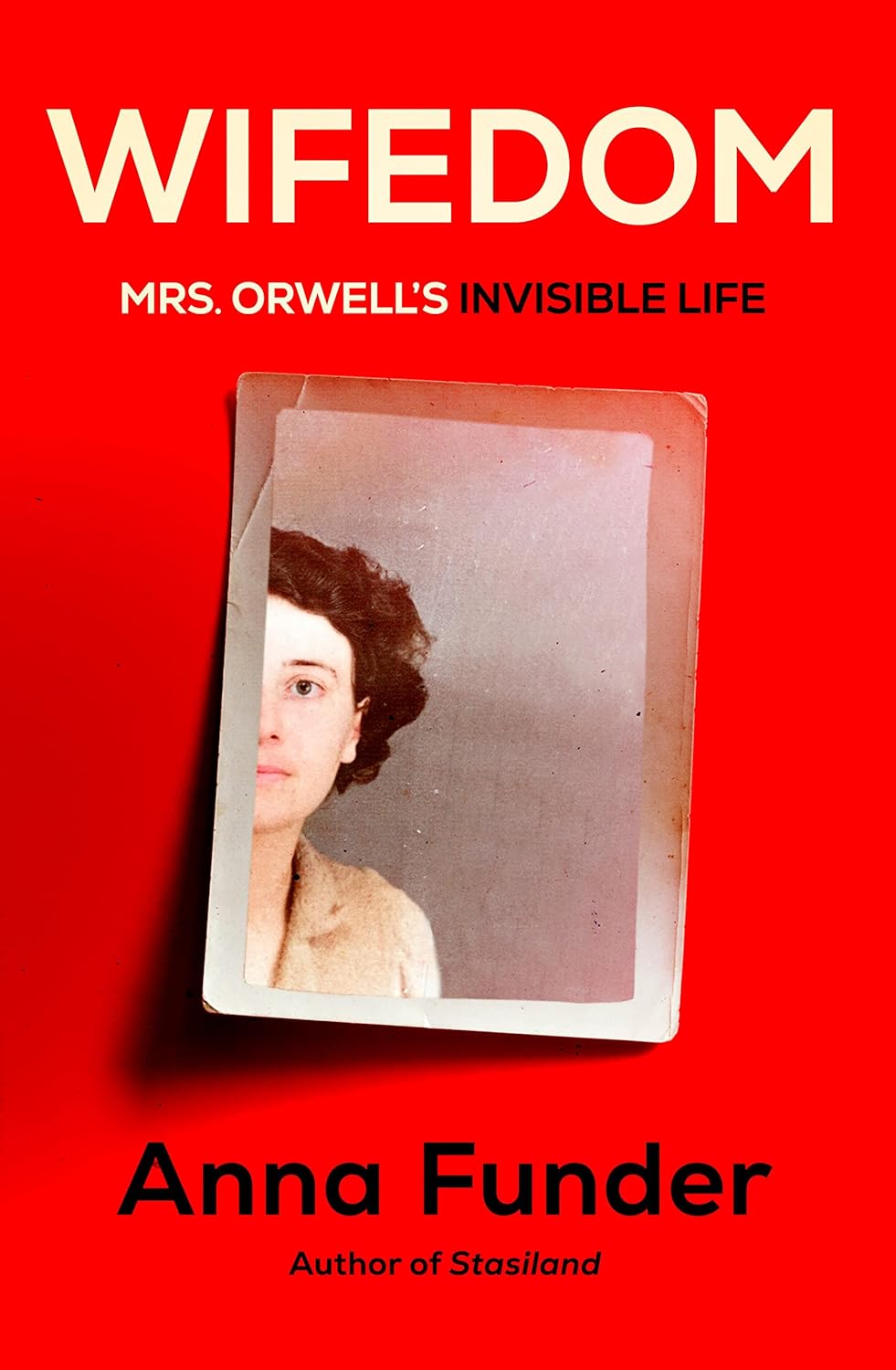

George Orwell’s contributions are many—though he did not achieve them alone. As with many men, it was the women in his life that made his success possible. Eileen O’Shaughnessy, who was married to the writer from 1936 until her death at age thirty-nine in 1945, did just that, even as it shrank her own horizons. What did it mean to be Orwell’s wife? Anna Funder’s new book unpicks this inquiry with precision, dexterity, and charm. Wifedom is not a biography, but instead an incisive investigation into “wifedom” and what it meant for Eileen, a poet with chronic illness, to inhabit the role of “Mrs. Orwell” until her dying day.

Eileen had what in her time was called uterine tumors, which caused vaginal bleeding, anemia, and crushing fatigue. Despite this, she was often the sole breadwinner for the couple, working full time outside the home so George could focus on his writing. She also was his typist, editor, and collaborator, using her poetic sensibility and humanist insight to help push George’s writing to new heights. Friends were in awe of his 1945 novel Animal Farm, both for its gemlike quality and in the departure it represented from his prior work. That was Eileen’s deft influence, as Funder lays out—one among many that have been carefully erased from the record of George’s life.

How were Eileen’s contributions made invisible, and by whom? Funder creates a hybrid narrative that craftily builds a multifactorial story. She lays out archival material, critically appraising letters and firsthand accounts of the couple by their friends and acquaintances, documents written both contemporaneously and later. At the core of the archival record are six letters written by Eileen to her best friend, Norah Symes Myles, discovered in 2005.

Funder looks closely at the ways language is used to erase women from historical records; she inspects Orwell’s own writing as well as the work of his biographers and overlays events that happened in the couple’s life with how those events are written about. For example, both Eileen and George went to Spain in the late 1930s to fight in the resistance, yet Eileen is entirely omitted from George’s account. Similarly, in Orwell’s first book Down and Out in Paris in London, his chronicle of living and working among the poor, he left out the wealthy aunt in Paris who offered him respite from his fieldwork. And pointing to the pernicious use of passive voice, Funder argues that many of Orwell’s biographers surgically erased Eileen as an active subject in George’s life.

In Wifedom, Funder brings some of the history to vivid life via speculation. She sees this not as writing fiction, however, but rather like “directing an actor on set.” Putting archival events mise en scène—the clinks of tea cups, the pangs of uterine cramps—allows the reader to become more intimately immersed in the world occupied by George and Eileen and to bear witness to the peculiar dynamic of their relationship. And in yet another writerly layer, Funder tells her own story of working through the project and what it has meant to her as a writer, wife, mother, and Orwell fan herself, wrestling with the complexities of gender, agency, and love as they relate to the craft:

As a writer, the unseen work of a great writer’s wife fascinates me, as I say – out of envy. I would like a wife like Eileen, I think, and then I realise that to think like a writer is to think like a man. It is to look from his perspective at what he needed and see how he got it. But as a woman and a wife her life terrifies me. I see in it a life-and-death struggle between maintaining her self, and the self-sacrifice and self-effacement so lauded of women in patriarchy, which are among the base mechanisms by which our work and time are stolen. What did she give and what did it cost her? I find this question so chilling, coming out of twenty years of intense life-and-home-making, that I prefer to think it does not apply to me.

Grappling with this personal tension, Funder’s reflexivity helps breathe contemporary life and immediacy into the book.

One aspect missing from Wifedom is attention to Eileen’s experience of disability. In one of her last letters to George, Eileen debated the cost of her upcoming surgery, confessing to him: “what worries me . . . is that I really don’t think I’m worth the money.” Perhaps she was just wanting comfort and reassurance from George (who was off in Europe leaving Eileen to handle, among other things, the adoption of their son). Or perhaps her feelings of guilt and shame for needing an expensive operation were a manifestation of internalized sexism and ableism. Regardless, Eileen’s health concerns were treated as hers and hers alone, while George’s tuberculosis was a family affair: Eileen enlisted her brother (a renowned thoracic surgeon) to ensure George received first-rate care, and the couple carted off to Morocco so George’s lungs could enjoy a dry winter; later, Eileen endured grueling, long train trips (after working all day) to visit him in a sanitarium, while she too was suffering from a disabling medical condition. Looking at Eileen’s life with an intersectional lens—how both sexism and disability worked to close in the horizons of her life —could have strengthened this already stellar book.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024