Baqytgul Sarmekova

Translated by Mirgul Kali

Tilted Axis Press (£12.99)

I first encountered Baqytgul Sarmekova’s stories last spring while driving with a friend across the endless steppe in southeastern Kazakhstan. Another friend had sent me a story by Sarmekova titled “The Black Colt,” and as we sped by vast herds of sheep and horses, usually tended by a lone “cowboy” on a horse, I read the story on my phone and was utterly charmed. Sarmekova’s acid-tongued narrator, bumptious wit, dark humor, and adroit compression made me realize at once that this was something new in Kazakh literature.

As we drove through an aul (village) near the border with Kyrgyzstan, the setting perfectly evoked Sarmekova’s story: villagers on horseback or guiding donkey carts hauling loads of dried dung past the occasional gleaming Mercedes. The old mosque and the houses where horses, cows, and donkeys grazed in the yards looked like a scene from centuries past—except for the telephone poles and power lines and a smattering of satellite dishes. It is this uneasy juxtaposition of old and new, tradition and modernity, that Sarmekova dissects in her stories.

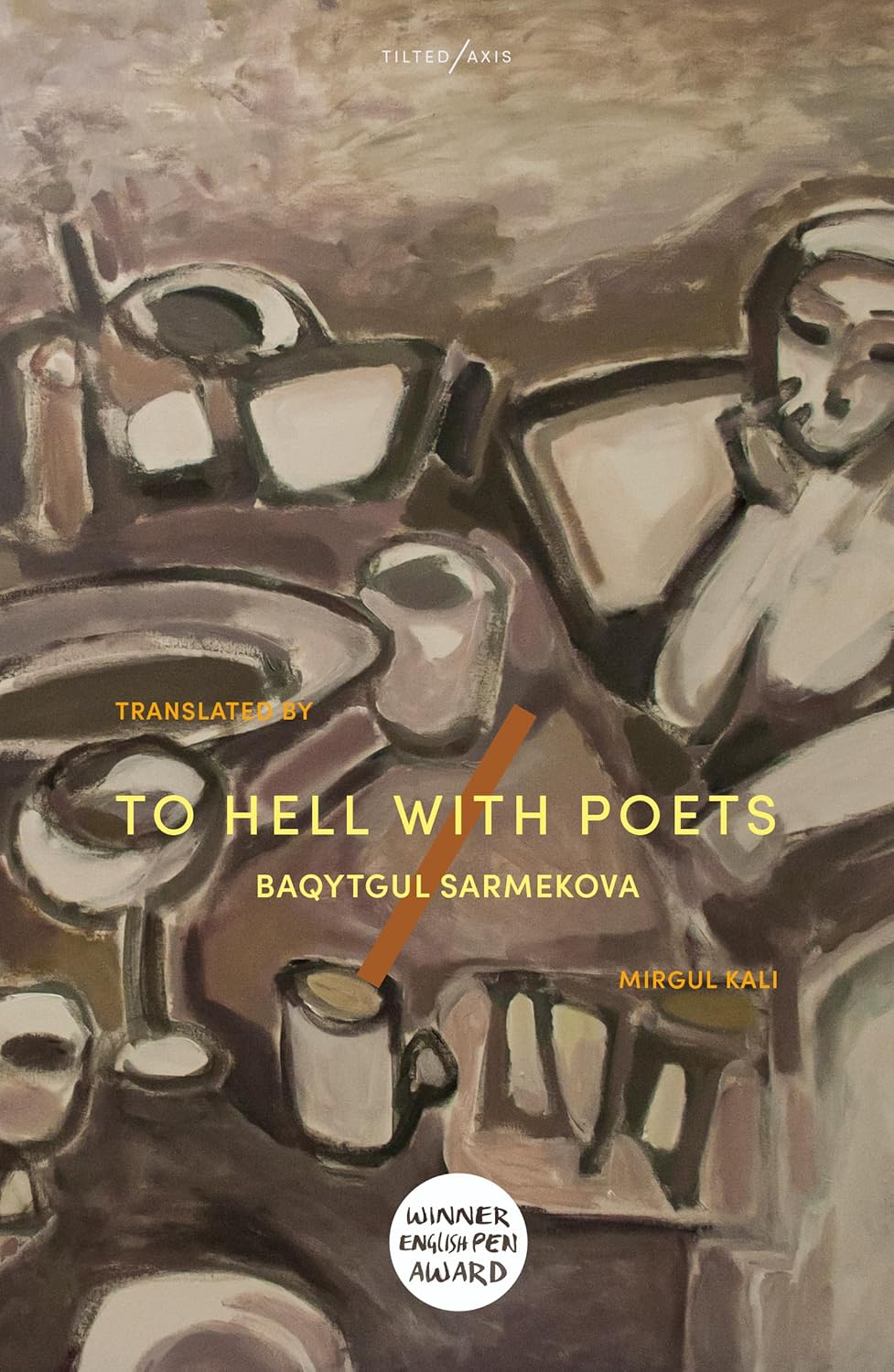

Fortunately, a collection of Sarmekova’s stories, To Hell with Poets, is now available in an adroit and nimble first English translation by Mirgul Kali. Kali foregoes footnotes or a glossary, but smartly retains a smattering of Kazakh words that are understandable in context and impart an authentic seasoning. Her translation won a 2022 Pen/ Heim Award, which paved the way for this publication by a notable UK-based small press.

Like “The Black Colt,” each of the twenty stories in To Hell with Poets is highly compressed, distilled like cask-strength Scotch, and all the stories pack a wallop far beyond their weight class. In “The Brown House with the White Zhiguli,” we witness the downfall of a once-proud man and the distinctive house that gives him status as his n’er-do-well son arrives on the scene with disastrous consequences. In “One-Day Marriage,” a mother-and-daughter pair of grifters travel from aul to aul bilking unsuspecting families by arranging sham marriages. In “Moldir,” a vain and urbanized woman recounts a visit to her rural aul for a high school reunion, determined that her friends would see “how removed I’d been from shabby aul life since I moved to the city.” In a flashback during a pause in the conversation, we learn of the tragic fate of Moldir, who was bullied and traumatized by the remorseless narrator. “Dognity” is an unforgettably powerful story narrated by a dog. It is not a comedic tale, but a harrowing four-page noir that evokes a sordid human web of lust, murder, and treachery.

Sarmekova’s prose is direct and unadorned. Her descriptions are acid-etched, her imagery often startlingly apt. She describes a bus pulling into town: “Dragging its belly across the ground, the groaning old bus had finally reached the bazaar at the edge of the city and spat out its passengers.” Elsewhere, a wedding guest’s dress is “so tight that her breasts spilled over the top like swollen, over-proofed dough.” In “Monica,” a woman returns to her native aul and the grave of her brother, which becomes an unwanted reunion with a devoted, simple-minded old woman. Sarmekova sets the scene deftly:

Soon, the yellowish, moss-grown roofs tucked between drab colored hills overgrown with squat tamarisk bushes came into view. The squalid aul looked like a sloppy woman’s kitchen. The graveyard, which used to be nestled at the base of the hills, now sprawled out to the edge of the main road. A march of corpses, I thought to myself.

The stories in To Hell with Poets are unrelentingly bleak. The characters usually die or experience various sorts of horrible or humiliating situations with all their hopes and dreams dashed. Yet Sarmekova’s authorial voice narrates black comedy with such verve and relish the reader can’t help but feel her pure joy in the act of storytelling, and this joy shines through, almost balancing the tragic outcomes of the characters.

Here is the description of Zharbagul in “The Black Colt,” an unlikely bride-to-be:

Before long, my grandfather returned with Zharbagul, whose bucket-shaped head bobbed up and down in his sidecar as they rode along the bumpy road. This was the first time we had ever met our aunty whose huge head, dark, rough, trowel-shaped face, and stumpy legs were a strange match with her thin pigtails, wire earrings, and lacy, ruffled dress.

Alas, on the next page, Zharbagul is jilted by death as the hapless Turar

stepped carelessly on the broken end of a downed power line and died, his body burned to a crisp. The adults who had gone to look at his body said, “He was grinning ear to ear when he passed on to the Great Beyond.” No one knew if he was beaming at the thought of his beloved Zharbagul or grimacing in pain when the fatal charge struck.

Mercifully, there are a few nostalgic tales focusing on two children growing up in a rural aul that offer some respite—Sarmekova likely sensed the need for a slow movement within her Breugelesque symphony—but mostly the stories of To Hell with Poets carry the reader like a carnival ride, evoking fear and delight simultaneously. The title story focuses on a love-sick would-be poet and a gray-haired mentor who seduces her after thundering out a “long-winded epic” at a wedding reception. In Kazakhstan, poets and poet-singers (akyn, zhirau and sal-seri) are still revered as cultural treasures, so the title To Hell with Poets is provocative—as if Sarmekova is throwing down the gauntlet with these bristling stories that careen across the landscape like tornadoes.

Sarmekova comes from Atyrau in western Kazakhstan on the shores of the Caspian Sea, far from the cultural centers of Almaty and Astana—which perhaps partly explains her originality. Atyrau also has the distinction of being where the Ural River empties into the Caspian—the Ural being the traditional dividing line between Europe and Asia. The city is, in fact, bisected by the Ural, so Sarmekova is from a place that has one foot in Europe and one in Asia, which seems fitting given the between-worlds ethos of so many of her stories.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union thirty years ago, the literary world in Kazakhstan has evolved, largely jettisoning Socialist Realism and its nation-building celebratory novels in favor of forms that encompass the complexities of an ancient nomadic culture rudely wrenched against its will into the labyrinth of the modern, commercialized, mechanized world. Literature in Kazakhstan today is thriving, but so far only a handful of works have trickled out in English translation, most notably Talasbek Asemkulov’s masterpiece, A Life at Noon, Didar Amantay’s Selected Works, and a pioneering anthology, Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan. One can only hope there is more on the horizon—and particularly one wonders what will come next from Sarmekova.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024