by Andrew Mossin

by Andrew Mossin

The first time I encountered Tod Thilleman was because of a book he’d published through the press he’s been running out of his Brooklyn apartment since the mid-’90s, Spuyten Duyvil. The book was poet Peter O’Leary’s Watchfulness (2001), printed on gorgeous heavy stock with an irresistible cover and irresistible poems to go with the lavish production. I’d made a mental note to add Spuyten Duyvil to a list of small, independent publishers that I’d come to know while in grad school at Temple University, but it wasn't until 2015, when I was looking to publish my third collection of poems, that I actually “met” Tod via email. Shortly after, I became part of the Spuyten Duvyil roster, one that includes a remarkably diverse gathering of contemporary writing in multiple genres, forms, and from a range of aesthetic positions.

Thilleman himself has long stood at the crossroads of innovative poetry that’s emerged from the long and multifarious roots of Donald Allen’s groundbreaking 1960 anthology, The New American Poetry 1945-1960. Spanning San Francisco Renaissance, Black Mountain, New York School, and earlier modernist movements, Thilleman’s poetics and poetry travel multifaceted roads through mysticism, Buddhist teachings, nineteenth century philosophy, cosmology, and anthropology, with stops along the way in Native American religious festivals, Mayan lore, and Dharmic revelation. It’s a powerful mix, carried across more than twenty books of his own writing that push at the borders of our national and communal consciousness. Thilleman’s new book, three markations to ward her figure (MadHat Press, $75) is no exception, a tour de force hybrid project that combines prose, poetry, paintings, and drawings in profoundly heterodox and singular ways. We spoke about it via Zoom in June of 2021.

Thilleman himself has long stood at the crossroads of innovative poetry that’s emerged from the long and multifarious roots of Donald Allen’s groundbreaking 1960 anthology, The New American Poetry 1945-1960. Spanning San Francisco Renaissance, Black Mountain, New York School, and earlier modernist movements, Thilleman’s poetics and poetry travel multifaceted roads through mysticism, Buddhist teachings, nineteenth century philosophy, cosmology, and anthropology, with stops along the way in Native American religious festivals, Mayan lore, and Dharmic revelation. It’s a powerful mix, carried across more than twenty books of his own writing that push at the borders of our national and communal consciousness. Thilleman’s new book, three markations to ward her figure (MadHat Press, $75) is no exception, a tour de force hybrid project that combines prose, poetry, paintings, and drawings in profoundly heterodox and singular ways. We spoke about it via Zoom in June of 2021.

Andrew Mossin: You grew up in Wisconsin in the wake of Donald Allen’s anthology The New American Poetry. One of the things that really caught me at the end of your memoir, Blasted Tower (Shakespeare & Company, Toad Suck, 2013), is when you talk about Gary Snyder's impact on you (and of course Snyder is one of the central figures in that collection). There’s a really beautiful section in which you talk about first finding Snyder’s work—you were particularly drawn to his 1967 collection The Back Country—and how it affected you and what happened later with a connection that would follow you to the present day. Could you talk a bit about that?

T Thilleman: Probably I was sixteen or seventeen, and I said to my high school teacher, “I'm going to write on Gary Snyder,” and he said, “I've never heard of him.” And I said, “Well, you know, he won the Pulitzer Prize a couple years ago.”

AM: So, this was someone who clearly didn’t know about contemporary poetry.

TT: No, I don't think there was really any poetry background; but he had us read Nikos Kazantzakis’s Saviors of God, which was odd for a literature class. And we later read his The Last Temptation of Christ too. And then this term paper thing was due, and I just hit on the Beats and Snyder as very accessible, literally visiting nature then writing about it. Real quickly, without any interpolation whatsoever. There's some bear shit in the trail and Snyder is there, writing it down. I thought, “Oh, I can do that!” I also liked the way the poems were on the page; the lines are all over the place. And then that got me into Mountains And Rivers Without End. Just the idea of writing, writing, writing, writing over and over and over the same kind of thing—but you travel, you’re on the road and traveling.

AM: This is a good place to ask you a question about your work in the long poem, because that's something that keeps coming up in your work, especially in three markations to ward her figure, which is all about various formations of the long poem. There are some big predecessor works in the long poem that you seem to be alluding to, at least formally—works like Anne Waldman’s The Iovis Trilogy, Theodore Enslin's Ranger I-II and Synthesis, and Ed Dorn’s Gunslinger. How did this latest long poem get started for you?

TT: I started writing iterations of the “longpoem” (that’s the term poet Ron Silliman uses to describe the sort of endless, multi-referential life work I’m engaged in) in the ’90s, and they grew out of just screwing around with letters, moving them around on the page, and then from that, figures emerged. I knew this was to be going on for a very long time, so I thought, “Well, it'd be a creation myth, and I can rewrite creation ad infinitum.” I think if you're going to be doing something for a very long time you have to work into it that you can rewrite it as part of its subject matter—the gestalt of what it's going to mean. And this thinking carries through each of the books collected in three markations to ward her figure, which go (in order) Three Sea Monsters, Three Shadow Inventions, and Three Natures, and each of these longpoems is part of the overarching longpoem that is really unending, a life’s work.

AM: There’s a tremendous amount going on in these books, both individually and gathered together, but if you could walk readers through what you’re doing, that would be really helpful to folks unfamiliar with how you work, and even some of those like me who are.

TT: It's all an extension of an ongoing investigation of image. What is image? What is figure? And, you know, we're talking about history and time and stuff like that. I go back to Duncan’s “Passages” series, which is a longpoem along the lines of Charles Olson’s Maximus or Ezra Pound’s The Cantos. I am also incredibly sensitive to the first numbers of Robert Duncan’s “Structure of Rime” series where the poet “spews images” at some figure who, presumably, presides over the poem. She is a figure of authority but also a source of the poet’s need to create more “images” toward her endlessly reappearing authority.

There's also language itself, which is the harbinger of all this presence/absence play, back and forth. I began to play around with seal scripts, early Chinese “oracle bones,” so these are early scripts. I became interested in the question of how the letters came about and how the figures grew out of all this that we take for granted as communication, aka poetry. In order to get to the actual composition, laying down my thoughts, feelings, whatever I'm encountering, I am at the same time running with visualization from one book to the next. You see the jellyfish exploding from H.D.’s idea of “lower body rising up to the head” and there are also large circular blobs: 0 0 0. And those figures carry into other re-creations of themselves in thought, word, and deed throughout Three Sea Monsters, the first of the three books collected in three markations.

AM: So the intent here is to provide these other stories related to the question of the image?

TT: Stories within images that you're trying to unpack and tell and truck with narration. I think the story, the storyline, is basically that of birth from the womb, while you have three wombs basically: three books, three wombs, and I’m talking about each of them. And the reason I have a copious amount of notes in the first book, that section titled “Notes on the Matter Within Three Sea Monsters,” is to talk about that quote from Duncan’s The H.D. Book, the monsters are everybody “talking” about poetry. And the one figure that's kind of left out is God. The thing on the so-called page, in the crotch of the book, travels up from lower body into the head.

There’s constant talk as well about female form throughout that book, then the next. It starts with the creation of the world—I just riffed on the Egyptian Nut/Nuit sky goddess, which was really there in conversation after conversation with poet j/j hastain, centered on the milk from light and the milk from breasts, back and forth. And then I get into indeterminacy with any and all terms. I would use that story, bringing it up over and over in various sections as it then becomes love professing/confessing; and I end with A Midsummer Night's Dream riffs. Are we just talking about a love story between a man and a woman, trying to communicate through a wall, a chink in the wall, which is another kind of opening? Or are there other ways for us to see into these relations that can sometimes seem imposed on us, when in fact there’s great creative energy attached to movement back and forth across the boundaries of male and female?

And then we have the Buddhist third book in the series, Three Natures. Literally the womb of compassion, shunyata means emptiness in Buddhism. It’s a very cosmic, stellar thing, and if you read, like, the Kalacakratantra, it's mainly related to YOU relating to your subtle body. The Linga Sharira or stars and the time being told in the stars, those constellations. And they were there from the beginning in Three Sea Monsters. And of course, you're going through the beginning once again. You're passing from one world to the next. You’re reenacting the beginning of your own life over and over.

AM: Is Buddhist thinking and conception a central beam of the work or one of just many different, related philosophical concerns here?

TT: I think it became stronger and stronger as I worked through each of these three books. Buddhism was there, I just didn't know a lot about what the terms were, and then I started immersing straight into tantric texts—and that's the whole thing about Buddhism, it's really based on the liturgy, the texts, and you're reading poems that have been left behind, discussing or riffing on major tenets over the last 2,500 years. You're dealing with the poetic aspect of “emptiness” that I have been showing. What is mortality? What is existence? And, turning to the book in which these poems appear, what about the page? How does blankness of the page, that Mallarméan concept that we get from Un Coup de Dés, literally “a throw of the dice,” figure into these questions of image and figure that I was talking about earlier? So, all of this is going on at all points along the way, but it’s not really one thing or idea or philosophy, but a synthesis moving through the poetry into a range of expression that seeks not to limit but to expand our consciousness as readers and thinkers, reading and writing poems together.

AM: Would you say that it's necessary or important for a reader coming into this text and other poetry of yours to have access to some of this background? Or is your work meant to make us work through the language and form as presented to us, to have us take this journey relatively unassisted?

TT: Well, there are clues all over the place, very intentionally left and shown and sometimes really isolated on the pages. There's an exercise in the Mahavairocanatantra where you're meditating in the Mandala, the four directions. And you're right in the center and supposed to take these associated vowels letters and colors that you've associated with terms and people and gods and things and take them apart and toss them up and let them land where they land. I actually did that on various pages. And then I re-associated these elements to see how they might appear from a different angle of inspection, a different arrangement. You can see that particularly in a section called “2pēL,” where I’m really working with open form, letting the lines drift down and across the page to catch that spell—or cast one myself! So that when you read the work, you’re integrating your own vision and vision is connected to sound, the elements at work as the lines suggest alternative readings, ways of understanding. No one route, but several.

AM: You do a lot of work with Carl Jung in three markations, especially in the “Notes” . . . What’s the importance of Jung’s work to what you’re doing in these books?

TT: Jung’s The Red Book (also called Liber Novus or The New Book) had just come out in English in 2009 when I started working on this, so it was kind of interesting that there was this whole parallel story he had wherein he immersed himself in the visual. He just did a book of these drawings and he kind of referred to it as, like, his other self. He didn't want to show anybody because they would think he was nuts, that he was trying to formulate his ideas, such as they were, in these stories and drawings, these fantasies and dream projections. They were huge, very big and very colorful, and he just kept at that for a long time, immersing himself in that visuality—completely parallel to what I was trying to do in composing my own text. Jung’s ideas are, in shorthand, not just this visualization, but immersion in general, a very blatant turning away from the so-called “factual” everyday.

Also, I wanted to get a lot of material together and kind of slap it around. And just see what would fall out from that. What does it mean to visualize, what does it mean to have an image in your head, or two; just to see the confluence of all of these ideas about what it means to see. I think you pointed out the one line in there where I was like: “Hey, mankind, why can't you shut up!” We can't use much talk when we’re looking into something—we have to be absorbed in the looking. That’s the ethics of the work, really, in the simplest possible way I can say it: Keep looking. Stop talking.

AM: It’s quite clear for all your work that sex and sexuality, different formations of sexuality, play a vital role. Could you talk a bit about the connections you see between and among these elements of human experience as they’re made apparent in your poetry?

TT: Sex is the primary relation to how you form any thing, whether you’re talking about a drawing or poem or anything like that. It's pure energy and that's really what you draw on, because, you know, in Buddhism there is a sense that the key you get from sitting, when you're practicing meditation, whether you're visualizing it or however you're engaging the Yabyum—father/mother—you're in that primal embrace. You're engaged in quietness, when you go to compose. I never think of sex any differently from that. I mean, when I start to write I get worked up and it just starts to come spilling out.

AM: And the poem becomes a record of that experience, of your experience in getting worked up and having the language spill out, as you say?

TT: No, not so much that the text becomes that, but the text for readers becomes a place of entry to different forms that aren’t just sexual, but phenomenal, pleasure-based. It's a way of engaging elementals. I'm not making any distinction between male and female. Other than that, they are missing entities. I don't want to assign extra roles to them in their mythic identity. They're already mythologized. So, I don’t want to give them a new label. I think when we're talking about sex, and pairing it up with how we're writing, I'm more interested in childbirth in a way, in gestation. In Buddhism there's the garbha, a term of gestation or womb, when you're holding while also impregnated with thought. The outcome of procreation is that new life, new form, and insofar as every myth and every way we talk about creation is about birth, my books are records of that process, that birth process that brings new life into the world.

AM: You’ve been publisher and editor of Spuyten Duyvil since 1992 or thereabouts. And you’re still going strong nearly thirty years later, while so many other presses have had to close for economic and other reasons. How have you managed to keep doing the range and number of books you have each year?

TT: Well, it’s been a struggle at points along the way, to be sure. The last incarnation, which has been over the last, like, five or six years, kind of went belly up and I was trying to avoid bankruptcy, which often happens with publishers, you just lose a lot of money. It's very difficult to sell books, and then you have to warehouse them and there's always a lot of problems that you have and there's just so much money you have to spend on everything. And I was moving at a clip and I had books getting into the chain bookstores and all this kind of stuff, but now things are different, right? I mean chain bookstores aren't as big a deal, so to speak, given the online options. People have made a big deal out of print-on-demand, but it’s just not that big a deal. It’s a way to produce/print/manufacture a book. Not as important as content, as the title list, as WHAT is being published. In other words, I want to keep the title list growing, with new and really good and interesting people. And they keep coming and they ARE out there. Then I want to make the books we publish available as much as I can to whatever book-buying public still exists. And just keep replicating that over and over.

AM: When did you know you wanted to be somebody who made editing and publishing a central element in your life’s work?

TT: We started everything off today by talking about Gary Snyder and all the small press stuff back in the 1950s and ’60s . . . I was acquainted with poetry through small presses from the beginning and I came to understand very early on that this was where the voice of poetry—at least as I understood it—truly emanated from. This was an American voice I heard and saw early on, and this is how you got it out, by publishing it yourself, printing it yourself, doing it in the basement, on your kitchen table, wherever you can and need to. Everybody cites Whitman and all the other people since Whitman who have published their own work, whether as stapled-together sheets or letterpress editions or full books. That’s the dream of community that the small press and its writers invent together. While that history is interesting and useful to know, as an editor and publisher, I'm more interested in building something and basing it on the content, like we take your book now and we show it to people who are interested in it alongside their lives and in this way we can keep people connecting the two together. This is how you keep the voices of your writers out there, bringing them into conversation with each other and with all the forms of the social that we have as part of our world in the twenty-first century.

Kate DiCamillo is one of America’s most revered storytellers. She is a former National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature and a two-time Newbery Medalist. Born in Philadelphia, she grew up in Florida and now lives in Minneapolis. Her newest book is The Beatryce Prophecy, which Ann Patchett dubbed “an instant classic” in her recent Rain Taxi conversation with Kate DiCamillo and Sophie Blackall (a replay of which can be viewed free of charge here).

Kate DiCamillo is one of America’s most revered storytellers. She is a former National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature and a two-time Newbery Medalist. Born in Philadelphia, she grew up in Florida and now lives in Minneapolis. Her newest book is The Beatryce Prophecy, which Ann Patchett dubbed “an instant classic” in her recent Rain Taxi conversation with Kate DiCamillo and Sophie Blackall (a replay of which can be viewed free of charge here).

by Andrew Mossin

by Andrew Mossin

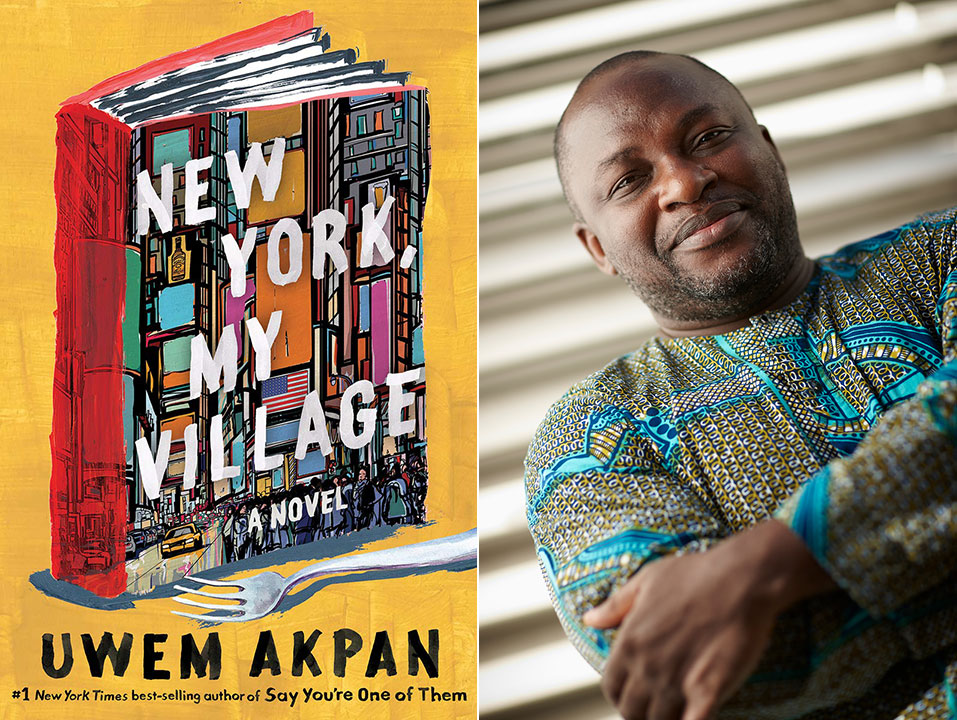

Okey Ndibe is the author of several books including the novel Foreign Gods, Inc., named one of the 10 best books of 2014 by The New York Times, National Public Radio, and numerous other places. Ndibe earned MFA and PhD degrees from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has taught at Brown University, Trinity College, and the University of Lagos (as a Fulbright scholar). He first came to the U.S. to be the founding editor of African Commentary, an international magazine published by the late great novelist Chinua Achebe. Ndibe later served as an editorial writer for Hartford Courant, where one of his essays, “Eyes To The Ground: The Perils of the Black Student,” was chosen by the Association of Opinion Page Editors as the best opinion piece in an American newspaper in 2000. His opinion pieces have been published by numerous publications, including The New York Times, BBC online, and the (Nigerian) Daily Sun, where his widely syndicated weekly column appears. He is currently working on a new novel and a series of essay vignettes based on his immigrant experiences.

Okey Ndibe is the author of several books including the novel Foreign Gods, Inc., named one of the 10 best books of 2014 by The New York Times, National Public Radio, and numerous other places. Ndibe earned MFA and PhD degrees from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has taught at Brown University, Trinity College, and the University of Lagos (as a Fulbright scholar). He first came to the U.S. to be the founding editor of African Commentary, an international magazine published by the late great novelist Chinua Achebe. Ndibe later served as an editorial writer for Hartford Courant, where one of his essays, “Eyes To The Ground: The Perils of the Black Student,” was chosen by the Association of Opinion Page Editors as the best opinion piece in an American newspaper in 2000. His opinion pieces have been published by numerous publications, including The New York Times, BBC online, and the (Nigerian) Daily Sun, where his widely syndicated weekly column appears. He is currently working on a new novel and a series of essay vignettes based on his immigrant experiences.

Saturday, October 16, 2020 • 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Saturday, October 16, 2020 • 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

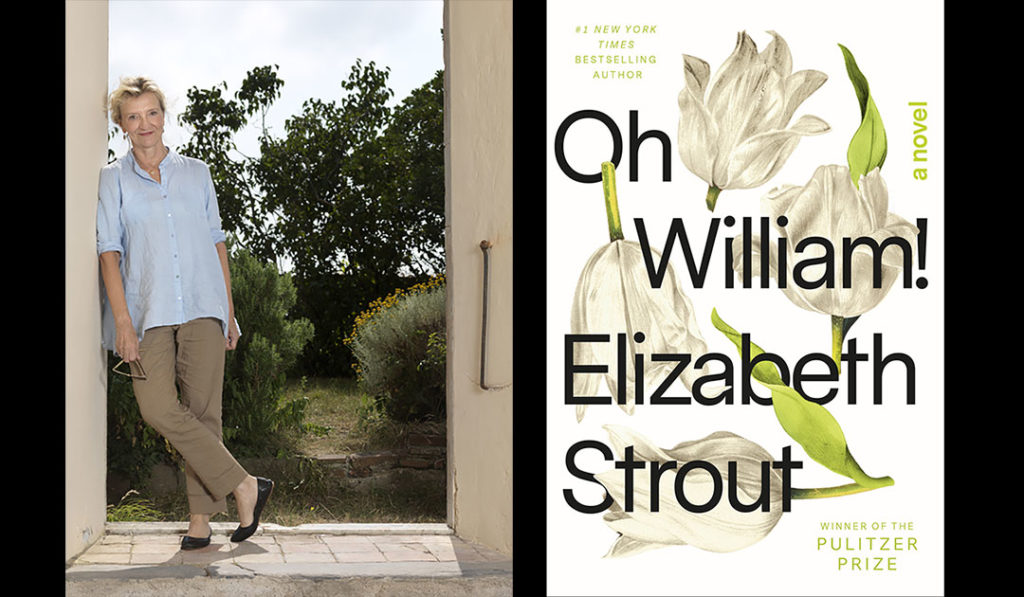

Elizabeth Strout is the Pulitzer-prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge, which was adapted into an Emmy-award-winning mini-series. Her other books include Amy and Isabelle, Abide with Me, The Burgess Boys, My Name is Lucy Barton, and a sequel to Olive Kitteridge, the 2017 Anything is Possible. She divides her time between New York City and Brunswick, Maine.

Elizabeth Strout is the Pulitzer-prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge, which was adapted into an Emmy-award-winning mini-series. Her other books include Amy and Isabelle, Abide with Me, The Burgess Boys, My Name is Lucy Barton, and a sequel to Olive Kitteridge, the 2017 Anything is Possible. She divides her time between New York City and Brunswick, Maine. Julie Schumacher is a professor of creative writing at the University of Minnesota and the author of multiple novels and collections of short stories, including The Shakespeare Requirement and Dear Committee Members, which was awarded the Thurber Prize for American Humor.

Julie Schumacher is a professor of creative writing at the University of Minnesota and the author of multiple novels and collections of short stories, including The Shakespeare Requirement and Dear Committee Members, which was awarded the Thurber Prize for American Humor.