by Alexander Dickow

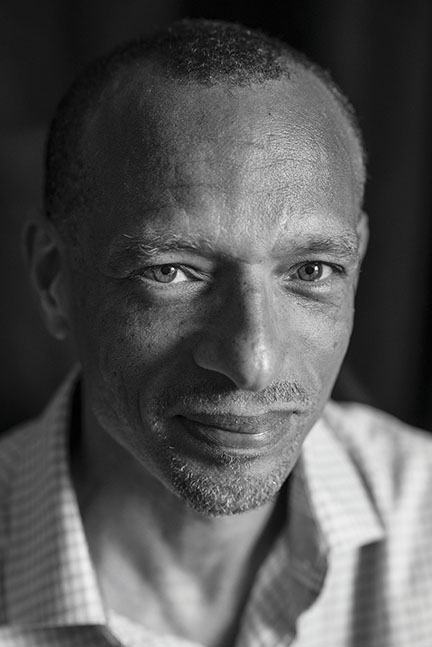

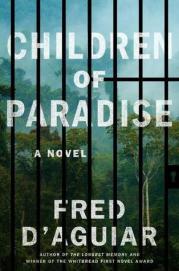

On November 18, 1978, in a gated religious settlement in Guyana, 918 people were poisoned to death at the behest of the preacher Jim Jones. The notorious cyanide poisoning became known as the Jonestown Massacre. Fred D’Aguiar’s Children of Paradise (Harper, $25.99) tells the story of impending disaster at Jonestown from the perspective of Joyce and her daughter Trina. Joyce begins to doubt and resist Jones’ indoctrination, and inevitable difficulties arise for her and her daughter within the Jonestown community. Presiding over the community is the caged gorilla Adam, who accompanies Jones in his grotesque and theatrical sermon-performances. The reader enters D’Aguiar’s novel through Adam’s eyes.

Fred D’Aguiar, a novelist and poet of British-Guyanese origin, has already written a collection of poetry surrounding the Jonestown Massacre, Bill of Rights (1998), a finalist for the T. S. Eliot Prize. But the event demanded renewed attention by way of narrative form. In Children of Paradise, D’Aguiar plunges the reader into the Guyanese landscape, whose lush, profuse life contrasts starkly with the oppressive, totalitarian atmosphere of fear and coercion in Jonestown.

As the following interview demonstrates, D’Aguiar continually returns to sites of collective trauma, exploring the possibilities of art to commemorate and understand History’s wounds. By giving histories to forgotten subjects—a slave in Feeding the Ghosts (1997), for instance—fiction restores a human face to men and women whose faces History and power have suppressed and erased. Even in journalism, D’Aguiar claims, the limits of mere facts make recourse to the imagination a vital part of writing. But the necessity of imagination is proportional to the writer’s responsibility in the face of History.

Alexander Dickow: Some people do very formal interviews where they have a list of questions, but I thought we’d just sort of converse naturally. I do have a couple of questions that are at the top of the priority list, as it were. The first is, have you read Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man?

Fred D’Aguiar: No!

AD: Oh, it’s a wonderful book, it’s very strange and a lot of English Department-types over the years have hated it, so it’s a controversial novel in some ways. It has people telling stories throughout, and they keep getting bogged down in epistemological questions about how much truth there is to the story—until the Cosmopolitan, a character, comes along and says, “I’m going to tell you a fiction,” and they can no longer get bogged down in these epistemological questions. So my take on this novel, and it’s only one of many interpretations, is that one of the saving graces of fiction is that it is detached from the real, and thus enables us to talk about moral issues, since we don’t have the epistemological questions anymore. So this leads me to my second question, which is: where is Jonestown as far as your research is concerned, and as far the writing process is concerned?

FDA: Right, well, typical translator, you cut to the chase! Thanks Alexander—that is, it’s good to be doing this and to talk about the book on a serious level, and that’s a serious comparison to start with, because the Melville of Benito Cereno is the one I know, and of course Moby-Dick, but in Benito Cereno he raises similar questions about credulity as asserted by a factual occurrence and its report.

So Jonestown. As you know, history has always trumped story, even though story is part of the spelling of the word history, because people set so much store by facts, and I totally understand why they do. I view facts as always coming to an end at some point, if you follow one to its logical conclusion. Reading journalism, I always come to a point where I feel this desire for the facts to give way to invention. It’s always that for me. It may be the habit of writing poetry, reading poetry, where you’re always invited to take a small sliver of fact and build on it a kind of edifice. It’s a little bit of an iceberg, where the stuff that’s on the surface and factually given to you requires a conjectural building that’s submerged and out of sight, but you’d better be aware of it because it’s huge. And I feel that about fiction, I feel the fiction part is the submerged bit . . . the bit where you begin to think and flesh out the lives that have fallen, once you’ve got the numbers right and who did the slaying and so forth, there’s this huge chasm of wanting to know about the lives, the impulses, what got them ticking before it was suddenly curtailed.

That, I think, is asking a bigger question beyond what the facts, a question that has to do with invention and imagination, and how they’re embedded in memory and recall. And this is true for holocaust studies, for slave narratives . . . I’ve always said, “Hey, remember the dismembered.” But because their names have been elided, they were hurriedly disposed of, mass graves and so forth, you know that you have to walk back in there with such care. You don’t have the usual journalistic tools, and it’s a scary responsibility—this idea that suddenly memory isn’t simply making things up, it literally is a re-member-ance and a reassembly of souls lost—it’s as big as that and I’m not scared to say that, I’m not embarrassed to make that claim for fiction.

AD: That covers a lot of ground, and I think we’ll come back to that question in other ways later on. Let’s talk now about your narrative choice to make the preacher a very unambiguous evil character. One option in a narrative like this is to see through the eyes of someone who’s taken with such a character, but instead we have Joyce, who has a certain amount of distance and mistrust and a critical sense where other members of the commune clearly don’t have the same skepticism. Did you consider portraying this preacher character through the perspective of someone who found the preacher seductive, and decided not to for one reason or another?

FDA: Yep. That’s a good question about time and the measurement of time in fiction. But it’s odd to think of when Jonestown began. It appeared to start when Jones was in Indiana in his late teens. He stood on street corners and preached to anybody who would listen, and he had the Bible as his text; he was really inspirational, and he leaned on the Pentecostal tradition of invention steeped in breath and utterance: if you can speak well and get someone’s attention and hold it, if you can control how you breathe in and breathe out, then utterance becomes ideology and it ensnares the listener. I thought, Jeez, if that’s the beginning, Jones’s early beginnings, that’s gonna take a thousand pages of fiction because from Indiana he goes to California, from California (after a number of years) he goes to Guyana, and I knew I couldn’t write a big book like that, linear, I’m not cut out for a 1000-page book, and I’m tired (laughs).

And then I thought, what is the real penalty of Jonestown? For me the real test for Jones was when he landed in Guyana, with his preacher ability polished and intact. He was free to either set up a real, ideal commune and say “let freedom reign” as it were, or go really, really . . . like Heart of Darkness’s Kurtz: “the horror, the horror.” Heart of Darkness is a shadow text in my book, I’m kind of giving it away by saying that, but I was really interested in Kurtz. Conrad’s is a weird novel, too, because someone tells you a story within which the principal narrator functions by taking over the telling of the tale, and the person who introduces it is no longer the person responsible for telling the story. The classic structure, that the further upriver you go, the more you go into the subconscious, and the more civilization falls away fitted with the beginnings of Freudian thinking. Conrad didn’t get it quite right in that he had black people become stick figures, as Achebe rightly pointed out, but what was great about the book was that it correctly portrayed the subconscious, the fearless throwing up of the hands with that “the horror,” said twice, once for shock and the second time for insight gained through unspeakable pain. Civilization was no longer going able to remain intact; things truly fell apart (as Yeats would later chant). That disintegration became a formal, narrative question for Conrad. I thought, what would it have been like for Jones to land in the middle of paradise, with all his authority, and then behave without ever being instructed by his wise jungle environment, this beautiful Edenic place, the lungs of the globe as the Amazon is known—Jones simply put up a barbed-wire fence around his total institution, and that’s how he ruled. I felt that moment of arrival in Guyana’s interior was the point of most interest for me, when Jones began to unravel. He had this kind of “the horror, the horror” moment in a sustained way, as if his time in the jungle were elastic, made so by his drugged mind and dulled affect and unpredictable temperament.

I wanted to start the book in the middle of the action (en media res!) and move toward some backstory to show that at some point important people with common sense paid attention to him, and he betrayed that common sense and trust. Joyce, for example, who loved him at some point, had some kind of implied sexual relationship with him, was at the center of his confidential circle, and then was expelled from it and then re-invited back in, roughed up a little bit, and so we know that something went terribly wrong with this guy that would make somebody the reader trusts in the story to no longer believe in Jones. For me the jumping off point was right in the middle of what Seamus Heaney called “the pool of the moment,” where you kind of dive right into the deep end of things as your starting point. You’re not going to wade in from the shore and walk gradually. I think, there’s a notion from Philip Larkin, the British poet, which I’ve repeated to students, about there being two types of poems: the first is the kind you begin gradually, as if you’d arrived at the airport and checked in, and boarded the airplane, fastened your seatbelt, and so the plane takes off and builds to the height that you want the poem to get to—typical narrative. The second kind of poem is where you open the title or first line at 35,000 feet. I realized I really like the 35,000 feet poem; I’m not into the gradual seduction of linear narrative anymore, I think it simplifies the lateral and quantum complexity of thinking, the way in which we work emotionally, intuitively and so forth.

So I began to feel that I should import that complexity into a narrative form, the novel, where the line’s at the margin, and you’re forced to read like that, but actually what you’re thinking and feeling is lateral, quantum, intuitive. I like novels and stories that do that: Wilson Harris (Palace of the Peacock), B.S. Johnson (House Mother Normal), the Virginia Woolf of To the Lighthouse, for instance.

For me, the main thing with Jones (introduced by dropping him in the jungle, not giving him a linear build-up from start to finish that would make his character credible), was to begin with the incredible aspect of his character, because what would follow next would be even more devastating than his psychological disintegration. It wouldn’t make sense otherwise. Even though you saw him being outlandish, it still didn’t make sense that he would take out a whole community. So the in-depth approach to his psychological state became a writing imperative for me. Readers already have all the facts of the story, but I still try and surprise them. I love novels that tell you on page one that everybody in this story’s going to be dead by page 500. Once you know that, the question for the reader becomes, what else is there to be discovered? In the novels I like reading, the “what else” is addressing Being, Consciousness—they’re more than slightly existentialist, but they include Freud, and some materialist obsessions as well, and as you know, we can’t go back after Marx and Freud. The novel since Freud has been by and large concerned with an interior landscape that takes on the world of politics but inhales it, interiorizes it, as a way of refracting it back to society. It’s in part an homage to Joyce’s corruption of that mirror and lamp binary, with the mirror as highly polished (which Joyce said wasn’t highly polished, Joyce said his mirror was cracked and dirty). Joyce admits a kind of interiority—“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan” in that opening passage was looking into a mirror, shaving, and that was meant to be how we should read his novel as he walks through his day in Ulysses.

AD: In relation to the Heart of Darkness connection, I think where that comes through the strongest is in the moments with Ryan in the forest, which seems to be an underside to the novel we only catch glimpses of as the story progresses. I didn’t think of Heart of Darkness at the time, but now that you mention it, it’s clear. I did wonder about another reference that you might comment on, and that is to Les Enfants du paradis, the 1945 film by Marcel Carné. Is that an accident?

FDA: Nothing is an accident in fiction! As you know, the novel is a hoover, a vacuum clearer which pulls everything into it. Children of Paradise, and I’ve said this elsewhere, is my second most favorite movie in the world ever. I’ve seen it every year like one would watch It’s a Wonderful Life or A Christmas Carol towards the end of the year.

FDA: Nothing is an accident in fiction! As you know, the novel is a hoover, a vacuum clearer which pulls everything into it. Children of Paradise, and I’ve said this elsewhere, is my second most favorite movie in the world ever. I’ve seen it every year like one would watch It’s a Wonderful Life or A Christmas Carol towards the end of the year.

One reason I like the Carné is that it does something that fiction, novels, and films haven’t done much since. In a lot of art, the evasive tactics are visible—what do you do with an imagination that’s apparently fenced in by a totalitarian regime, as was the Occupation of France by the Nazis? Secondly, all the things he does with the play and the theater. They say that all the world’s a stage, and it’s impressive for him to be so Shakespearean in his questions, but using film to do that kept the link between stage, audience and location in a way that insisted on the links between art and life. He was forcing us to think about plays, about actors walking the boards, about the audience. The richness of it, the language, the wit, the doubling and the texturing of the movie, with little tiny handkerchiefs and flowers as motifs and so language driven! It remains to this day one of the most complex cinematic palettes I’ve seen. It gives me chills every time I watch it. I’m still surprised by something in the corner—oh, there goes that acrobat, I saw him earlier. I think it’s one of those things that speaks to all the genres, too—it seems to be cross-genre, multi-genre in a weird kind of way, because of all the self-referentiality, the theater, seeing shadows of what was clearly a set being constructed, hearing some of the tricks about how they got perspective in there and depth of field . . . oh man! When I go back to it, it’s a template for me for all kinds of things that have happened in cinema before and since, and then the limitation of what the cinema has become in our day, in terms of the big things that are made. We’ve lost ground in terms of the art form growing alongside a growing and sophisticated audience. Instead, there has been a dumbing down.

For my novel, I made sure I didn’t put the article in there: it’s not THE Children of Paradise. I wanted people to think of paradise in terms of real children, and then of paradise denied, because the childhood that we may associate with those young bodies is denied. So that was my thing, but the film is always in my head.

AD: I’m also a Carné fan, so I was completely plugged in to what you were saying, but what I thought of was the totalitarian feel of this commune. It’s a little allegory of a totalitarian regime, with all the abuses of power. And I thought that felt like a connection to the film, which is supposed to be an allegory of France under the Occupation. It seems to me also that this is a novel about the consolatory power of fiction. It doesn’t provide any tidy answers, but it asks whether fiction can recuperate these lost lives in a way that’s effective in some way.

FDA: Absolutely.

AD: Could you comment a little bit on that, and how you arrived at your particular ending as well? I felt that the ending was very finely crafted, I was quite impressed.

FDA: Thanks for mentioning the craft element, because out of that perspiration and labor I hoped to orchestrate certain effects to do exactly with that idea of trauma. And it comes from trauma theory too; if you revisit a site that’s been vandalized, what is the purpose to walk over where bodies were laid low? Why breathe life into them once more as an historical and fictive undertaking long after the event? What’s the point? In the end of the novel, there’s a point where as narrator I hold a charge and responsibility of the story, and Trina comes along and takes it out of my hand. Because at that point, the history of her outcome is so clear in our heads with everything that came before that there’s an inevitable end that I would have had to walk into, which is the queuing in front of the vat in the story, and taking the cyanide, Kool-Aid, and valium mix. I didn’t want to go there, and I was very glad to have a child say, “my interior life, which is mine, not my mother’s, not Jones’s, is not going to capitulate to this inevitable history.” And if I don’t, what use is it to a reader removed from that event by thirty-five years? It’s not so much about those who died and the kind of slippage and the surrealism of avoiding that, nor is it written solely to suggest possibilities that were curtailed for everyone who fell, it’s about my place as remembering the occurrence of the event and returning years later to a history that matters because I’m invested in the Guyanese and American landscapes.

One question I ask is, what’s the point of History as instruction for the present? So it’s a bit more than Faulkner’s “the past is never past,” it’s about its ever-present quality sure, but also about its insistence as being a site for instruction—not cure—provocation more than cure. You’re provoked into thought; there’s no guarantee you’ll get something out of it, you’ll feel something, but once you feel, there is an intelligence informing that emotional stirring that hopefully will take you to some place on behalf of those who didn’t have a chance to go there, that will help that history, and not make it passive, but something that absolutely influences anyone who’s prepared to engage with it in ways that are a little bit hurtful, risky, dangerous, but enriching, absolutely enriching as narrative, enriching as an emotional cluster of things to do with ideas that you want to bury in detail and not have up front, allow them to surface in the reader’s body, once you plant them there in the emotional reality.

My concern was that I had so many thoughts about what happens to time if you reimagine it, if you translate from an historical event to an emotional reality, as a lot of fiction is trying to do—how do you enshrine in those details the ideas you take and pirate from that historical moment to reconstruct as an emotional construct? There’s a risk involved, but imagination is a fantastical, limbic, chthonic tool that enables repeated returns to dangerous places. I’ve talked to young people hearing about slavery who are black; they can’t believe that this is a part of their history, they get enraged, and it’s just like grief, it’s exactly like grief! The holocaust studies and the trauma theories I’ve followed to do with Nazi camps, it’s exactly the same weight. You look back with astonishment and hurt; all the stages of grief are built in. “It mustn’t happen again” is usually one of the lessons, “How do I stop it, how do I make sure everyone knows?” And if the historian is working, the geologist is working with landscape and so forth, what is the fiction writer going to do but build a landscape for those who didn’t have their names registered? Because in Oakland, CA, there’s a mass grave for about two-thirds of Jonestown, people are laid to rest there, many of the kids are in double coffins because they were not claimed, not identified. What an erasure! And it’s chilling, it’s horrific, it makes the idea of writing fiction really compelling; if you go there, you better have a good reason for going back into trauma, and you’d better make sure your art is up to scratch. So by the time I got to the end the responsibility was huge for me, it was hurtful for me. I’d done so much historical research, listened to so many tapes of Jones; if I heard another tape I was going to break, because I couldn’t believe his continuous indoctrination of them and how crude it was, and how unrelenting and how much it resembled a total institution.

Erving Goffman wrote a book called Asylums, which talks about how they take you and drop you in a space, and it’s so totally enrapturing for you that when they release you, you’re remade in the image of the institution, and it resembles prisons, it resembles concentration camps, what they try to do, and they give you a uniform, feed you when they say, make your diet small, tell you you’re small, you know, they reconstruct you, and then what they try to take away from you is this humanity that you’ve got to really fight to keep alive, to remember something—there’s a book I’m reading right now by Otto Dov Kulka called Memory and Imagination about what it was like leaving the concentration camp Birkenau at age eight. It’s hard to read, really painful. He called it Memory and Imagination, he didn’t say History. He was really pushing History away for a reason, and that reason appeared to be that he was relying on a reconstruction of it in his own terms, and wanted to enshrine in there an emotional integrity that belonged to him. Not to deny the historical truth of it, but to say, “When I reconstruct it, it means this to me, and it’s my whole nervous system extracted and laid bare in language.” It’s a wonderful book and it reminded me of slave narratives, thinking about slavery, and the recuperation of a loss, and then the individual body, giving it value once more, not as a piece thrown away, but as an individual, hard to quantify, you can’t get their dimensions by walking around them, because they have a depth that you can never quite sound out once you credit them with a story. And that’s also from being a poet. I began as a poet so I’m always thinking, “Corrupt the narrative, circle, go downwards, don’t go forwards too much!” Because I do think that’s how the truths are, they’re soundings. Heaney called it soundings when you throw out something as surveyors do and it goes, waiting, and surprised by the long wait and so thinking, oh my goodness, that thrown thing has not landed as yet, nothing’s come back, can’t be! You’re on psychological terrain in that gesture of the flung thing that never lands on solid ground, that keeps going, that’s the kind of depth the novel plumbs.

I also need to say a bit more about Wilson Harris, born 1921. Wilson Harris is a Guyanese writer and a surveyor who went into the interior of Guyana as a young man surveying in his early 1920s, and was committed to writing mythical realist type things. When he tried to measure the rivers and the trees and what surrounded him in Guyana’s interior, the Amazonian interior, it destroyed all of his notions of linear narrative, because when he took five steps and sounded a river out, it would say forty feet. Five more steps, he would hit a rock escarpment, that took it down to eighty or 120 feet, but it was such a sudden drop and such a dramatic difference from the last sounding, he was thinking, what does that rock strata look like? And for him it was like a mountain upended, he was trying to find ways to talk about it because it was so dramatic. And then he talks also about walking into weather from sunshine into rain in a few steps and vice versa, that the forest would have this little shower going on just over there, shhhhh, and he’d watch it thinking, it’s raining, right there. And you’d walk right into it and see the way in which the weather was already being remade to once again move along a few feet—you get a real sense of it as an ecosystem by watching it, walking into rain, walking out of it, being wet by mist, dried by the sun, immersed in it all. I think he just felt the realist sentence could no longer serve his imagination, because his geographical reality had made exterior something he intuitively suspected as a writer: it wasn’t going to be a linear progression, hitting the margins and making sure you carry on that walk; it would have to be lateral, and it would have to be quantum.

AD: One of the ways the novel functions is this tension between the Guyanese landscape on the one hand, which is sort of everywhere, and then the narrative movement on the other. So in your terms, the landscape is working downward, as it were, and the narrative moves forward?

FDA: Yep, there’s this idea that landscape is not a passive backdrop, it isn’t like you’re on a set where they’ve constructed the frame in front of which the actor is projected to you. That’s the most common view of landscape as passively set up. When it’s active, it becomes a character in the novel. This is especially true of the Ryan sections, which are exactly the ones you mentioned. One confession I must make: there are poems in there that I included and simply removed the line breaks; three or four instances where a kind of density breaks out, and it makes you slow down a little bit, and that’s because I took out the line breaks and hit the margin, because I thought, I can’t leave this out, it’s a poem, it can’t go in, it’s gotta be a line of prose—don’t tell anyone, Fred! (laughter)

AD: Those were probably my favorite parts, where suddenly the verbal intensity was ratcheted up a notch!

FDA: And that’s when I thought the landscape would take my prose and wring it a little bit, put it through something that would alter its specific gravity. I wanted to say, “Look, look at the landscape influencing how consciousness unfolds, or is displayed. Look at the dark that Ryan talks about, that he says will pick him up and drop him down, what does he mean by that? But you decide, reader.” In other words, he really is that landscape and conducting it through his body, and his senses. Those moments I kind of jumped up and down when I got them as poetry, and then realized, don’t take them out because poetry doesn’t work—Henry James said for every poem you put in you lose a reader, or something like that—if you want to kill your audience, write a poem, or tell them a dream. So I thought I’ve got to put in a dream, because he said it can’t work, got to have some poetry in there. But then I relented and thought, you know what? I won’t declare it up front to the reader, I’ll let the reader kind of slip into it without realizing.

AD: Right, well, and Adam of course is the perfect incarnation of this sort of strange agency that Ryan’s surroundings take on for him. Is there anything in particular you’ve wanted to talk about?

FDA: I want to say something about the spirit—about, if you don’t go to the usual sites, places where spirituality is being looked after, let’s say the Bible, as a primary text for Jones as a young man, if Jones doesn’t use it properly as he did not in the latter stages of his life, is there a secular way of re-invoking that spirit of instruction and the growing of conscience? I’m interested in imaginative ways of saying that I acknowledge that in each of us there’s some spiritual hunger that needs to be answered in various ways. And the Blacks and the poor Whites who followed Jones were trying to address that question, and he told them an answer which he betrayed. Now, if you’re writing a novel where the Bible, the most you can take out of it is a little quote from Corinthians and if that’s your only concession to the Bible and if Paul’s thesis is guiding you, because you know it a little bit, what do you say if it’s a secular vision that you’re trying to reconstruct, and talk about catastrophe and trauma? Leaning a little bit on the Bible, but not a lot, where the imagination is a place you’re going to, and that’s a contemplative act, and the cathedral is a different kind of cathedral. I got interested in that as a big secular question, once I’d set the Bible to one side, having already set up passages in there.

AD: I wondered about that, actually. I thought at first this is just going to be sort of a screed against religion, but that’s not at all what it’s about. There’s absolutely no ambiguity that the preacher guy has perverted this beyond all recognition.

FDA: Right, exactly, it wasn’t the Book’s fault, it was the messenger. He had done something bad with the message. But that still left a hunger to be filled, not so much in the dead, because they had paid a terrible price for trusting him so much; it would be for the living, in a secular space. What would that question be about the spirit and about that spiritual hunger, which is clearly in our bodies, based on the quest, repeated quest for truth(s) or some kind, various kinds? That’s why we see these failed repetitions with the Branch Davidians and so on, the small independent spaces where people think they can create an ideal on earth and address that spiritual hunger, as a daily routine. And it’s like taking Proust and infusing it with—it’s all spiritualism, it’s not mundane details, when you put all the details together, they create a ferment, which is an account for your day, which then becomes, through materiality, an account for an interior thing that’s hard to pin down.

The book has a spiritual center to it, and hopefully it will point the way back to the declaration of faith, hope, and love that fronts the book. I’m hoping that when they get to the end of the book, the last word is “love,” literally, and I had to craft that, to get to that, I had to play with/in the language some, in order to point readers back to the epigraph and forwards to the end. And also, show the lamp (no mirrors cracked or otherwise alas) in the middle of this place, that’s been ignored by Jones. That there is a shining beacon still going strong, and it’s got a half-life of maybe 6000 years is my hope for a good novel, but what do I know.

AD: The Captain seems to me to be the figure for that sort of enlightened spiritualism that doesn’t sacrifice critical thinking in the novel.

FDA: Exactly. He takes Joyce for a walk in the woods and behind that waterfall, and he asks her to listen to and into the forest. In that scene he’s trying to tune Joyce in and to a kind of geographical reality of their actual surroundings as another approach to spirituality, because she’s gone through this terrible baptism with Jones that has left her a little cynical and largely stunned by him. So for her to be once again reawakened to a sensuous life, and in that sensuality leading to a kind of knowledge and a reengagement with the spirit, the Captain would be her guide. And Adam of course would similarly embody the jungle, hinting at a kind of starting all over again, a different view of Eden if only Jones were to pay attention. So there’s a lot of riffing on things with symbolic value to a culture of reading and I shine (sort of) little torches to various edifices of our thinking and refinement and sophistication of humanist (with a sprinkle of historical materialist) thought. I didn’t want to go into it too much in the novel because those ideas are tried and tested and self-explanatory. Once you (as a reader) going into Adam’s name and you riff on his name, it takes you back to the first cause, problematic innocence versus experience and stories about beginnings, probable endings and so on.

AD: It didn’t need to be heavy-handed; Adam is enough, the name is enough.

FDA: There you go! Yep, that’s the thing with writing too, it’s all by implication that you kind of create felt alternates to ideology, but if you were to walk with ideology any more declarative than that, it tends to corrupt the narrative. That’s the funny thing about ideology (everything is and isn’t laden with it): you can almost say look, I had to shake away all the research, and all kind of alienating arguments before I could write the book. But, and then you hope that with the embodiment of characters and so forth, and their own vocabulary, that once again the ideology will surface, but with a new life-force, and a kind of breadth and freshness that those people will give it. Otherwise it becomes an argument. I think Yeats said, “Out of a quarrel with others we create propaganda; out of a quarrel with ourselves, we create poetry.” That binary isn’t exactly true—it’s more of a commitment to the self by an avid awareness of both, it’s actually the outward thing in society made inwardly contemplative; it isn’t that you have one thing out there and one thing in here, and one is propaganda and one is poetry. When you’re looking out, there is a coalition of the public and the private, and that’s what I’m interested in. What if the way you’re committed to society is so deep it’s actually a social contract, even when it’s private when you start off, even though you’re on your own seated at your desk with multiple drafts? You’re seeing communities, you’ve got terrible stories from history pasted on your wall, Germany in the Second World War, the Atlantic slave trade . . . Those are things I look to as instruction because I’m living just after those times, and watching how they’re instructing our present, watching our present make mistakes, the same mistakes, the same amnesia, almost willful, and thinking, “Come on, why can’t those crucibles (lived, urgent, and eradicating millions) be endlessly instructive?” It’s not instructive because there aren’t enough stories about it. The more stories we have about it—for each generation, in all kinds of genres—the more likely we are to get those lessons to be ever present.

Writer and collagist Thomas M. Cassidy (aka Musicmaster) is a fixture in the international smallpress/mail-art community, and a board member with Cheap Theatre and Patrick's Cabaret, both in the gluing town of Minneapolis.

Writer and collagist Thomas M. Cassidy (aka Musicmaster) is a fixture in the international smallpress/mail-art community, and a board member with Cheap Theatre and Patrick's Cabaret, both in the gluing town of Minneapolis.