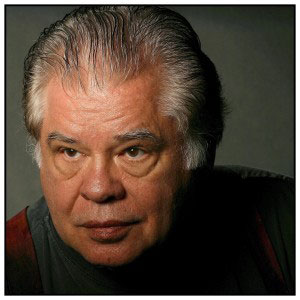

photo by Tom Wallace

by Stuart Kendall

For many readers of contemporary American poetry, Clayton Eshleman needs no introduction. His poetry, essays, and translations have been a fixture of the postmodern sensibility in leading poetry magazines nationally and internationally for more than five decades. It’s been honored with the National Book Award in Translation, a Guggenheim Fellowship in Poetry, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Rockefeller Study Center residency in Bellagio, Italy, and other awards, including the Landon Translation prize from the Academy of American Poets, which he has won twice.

The two magazines Clayton Eshleman founded and edited–Caterpillar and Sulfur–provided crucial outlets for both emerging and established poets that shaped discussions of poetry, the arts, and politics, over these same decades. Taken together, they provide a vital prehistory to our poetic and cultural present. A Sulfur Anthology (Wesleyan University Press, $27.95), edited by Eshleman, skims the cream from 11,000 pages of poetry, prose, and archival materials.

Eshleman’s own work, however, continues to unfold. His most recent collection is a gargantuan gathering of fifty-five years of writing entitled The Essential Poetry (Black Widow Press, $29.95). As deeply personal—and indeed intimate in detail—as it is political in its human sensitivity and occasional wrath, Eshleman’s writing resists both easy categorization and easy consumption. The poet’s sensibility serves as an open site for a restless and shifting investigation of identity that transcends, via translation, the comforting borders of a national language and ultimately descends, through layers of historical and cultural formation, into the depths of human soul-making, in particular as chronicled in Eshleman’s book Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination and the Construction of the Underworld (Wesleyan University Press, 2003). Eshleman’s entire corpus can be read as an extraordinarily complex, poetic “anatomy” of life, art, and politics in our times, combining poetry, prose, translations, and edited works, original writing and research, subjective and objective forms, all coiled together as multiple perspectives on and reflections of one another and of our world.

Eshleman’s own work, however, continues to unfold. His most recent collection is a gargantuan gathering of fifty-five years of writing entitled The Essential Poetry (Black Widow Press, $29.95). As deeply personal—and indeed intimate in detail—as it is political in its human sensitivity and occasional wrath, Eshleman’s writing resists both easy categorization and easy consumption. The poet’s sensibility serves as an open site for a restless and shifting investigation of identity that transcends, via translation, the comforting borders of a national language and ultimately descends, through layers of historical and cultural formation, into the depths of human soul-making, in particular as chronicled in Eshleman’s book Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination and the Construction of the Underworld (Wesleyan University Press, 2003). Eshleman’s entire corpus can be read as an extraordinarily complex, poetic “anatomy” of life, art, and politics in our times, combining poetry, prose, translations, and edited works, original writing and research, subjective and objective forms, all coiled together as multiple perspectives on and reflections of one another and of our world.

Stuart Kendall: From the very beginning of your career, or even from the beginning of your interest in poetry, you have been deeply engaged with translation and editing alongside your own writing. As a translator you’ve worked extensively with Spanish, French, Hungarian, and, to a lesser extent, Chinese language poetries. Your editorial work has been even more wide ranging. At the same time, your writing is deeply American, deeply concerned with your formation as a North American white male, and deeply concerned with the United States as a political entity, however flawed. In light of this, I’m wondering whether you might consider yourself a kind of transnational poet or, put differently and considering translation and editing is a kind of border-crossing gesture, whether you think this kind of border crossing is important for poets or poetry, either individually or collectively, outside of your own personal practice.

Clayton Eshleman: To your language list, I would add Czech, as I worked with Frantisek Galan for some six months on Vladimir Holan’s thirty-one-page masterpiece, “A Night with Hamlet.” We ended up with a few dozen problems we could not solve, so Michael Heim and I flew out to Austin TX where Frantisek lived in 1984 for a week and the three of us went through the poem word by word. Our final version with a note on Holan is in the 2005 edition of Conductors of the Pit.

Back in 1987, I entitled my first collection of prose writings Antiphonal Swing, based on the last line of Hart Crane’s “The Bridge:” “whispers antiphonal in azure swing.” At that time, I identified the “swing” as being between the erotic and the artistic, as well as between prose and poetry. I also drew upon the word “anatomy” (after Northrop Frye’s referring to Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” as an “anatomy”). Frye wrote that Blake’s poem was less a dissection than a composite work that included as its “members” many of the forms and strategies of the art of writing. I think, then, that my “transnationality” as you put it, or “border-crossing,” in an attempt to avoid the conventional pieties that inform so much of contemporary American poetry, involves a number of strategies: civil obligation (I prefer “civil” to “political), ekphrastic explorations, probings of the feminine as source and power (Barbara Walker’s A Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets was a wonderful fount of information in this regard), and my twenty-five year investigation of what I came to call “Upper Paleolithic Imagination & the Construction of the Underworld.” As I wrote in the Introduction to Juniper Fuse, “To follow poetry back to Cro-Magnon metaphors not only hits real bedrock—a genuine back wall—but gains a connection to the continuum during which imagination first flourished.”

In regards to civil obligations: given what the American government has been doing throughout the world from the end of World War II on, the American mind, into which news spatters daily, is now, more than ever, a roily swamp, at once chaotic and irrationally organized. The fate of American Indians and African-Americans is entangled with this complex. There is a whole new poetry to be written by Americans that pits our present-day national and international situation against these poisoned historical cores.

SK: Is it too much to say that there is a double movement here: a movement away from those forces of restriction and disarticulation—the conventional pieties, the predictable and the aesthetically acceptable—and simultaneously a movement toward something else? I’m reminded of your take on Charles Olson’s “istorin, to find out for oneself” where you “put the stress on ‘out’ or exit for the self,” in the introduction to Juniper Fuse. As well as your remarks on Olson and Antonin Artaud in the first chapter of Novices: A Study of Poetic Apprenticeship, where your point is that the poet is always “stuffed as well as empty,” stuffed with stories and figures, “all the initiations and stories of imaginative art,” as you put it, but also empty, unformed, in Olson’s term “zero.” On the one hand the poet’s project, as you describe it, is self-consciously critical—an act of disobedience—and on the other its goal is the emancipation of the self. How do you balance these tendencies, if in fact they are in competition with one another?

CE: The dichotomy that you appear to be addressing can also be proposed as ego vs self. I think of the ego as the chauffeur of the self, the conscious mind vs the subconscious (possibly activated in the process of artistic creation) and the unconscious, which most of us only experience, and then usually in a confused way, in dreams. Northrop Frye has written, around 1990, that “What is needed for creation is a new bicameral mind in which something else supplants consciousness.” I am not sure what he had in mind as this “something else” but it must involve some form of visionary activity, which could include hallucination, and might be a way of dreaming awake, or a mingling of the unconscious and the subconscious minds. There are aspects of the poetry of Antonin Artaud, Aimé Césaire, and Robert Kelly, for example, that engage what I think Frye has in mind here.

My Novice comments concerning the poet being “stuffed but empty” probably are more relevant when applied to apprenticeship than to the work of mature poets. “Stuffed” at least in my case was the situation I found myself in while living in Kyoto in the early 1960s when the full weight of what seemed to be involved in becoming a poet swept over me. I was “stuffed” with the unexamined first twenty-seven years of my life, and facing for the first time the sexism, prejudice, rule following and acting out of what Indianapolis had proposed that I was. The weight of all of this sealed me up when I tried to write poetry. Thus “stuffed” got reprogramed as “empty,” or blocked. In desperation, my being cried out for a vision, or some indication that my poetic apprenticeship (which I had decided by early 1962 was to be a translation of Vallejo’s Poemas humanos) meant anything at all.

As some readers will know, I had a vision at this time: that autumn I was in the habit of reading in the backyard of our Kyoto residence by the web of a large red, green and yellow garden spider. After one stormy night, I went to the persimmon tree with the web to find it torn, and the spider gone. I had a very peculiar reaction to this “loss”: for several days I felt nauseous and absurd. A week later, after having tea with Joanne Kyger north of Kyoto where she lived with Gary Snyder, I got on my motorcycle and headed back into the city. As I described in Novices (in greater detail than I will do here), I suddenly began to hallucinate and, terrified that I would have an accident, pulled into the parking lot for Nijo Castle tourist buses, got off the motorcycle and began to circumambulate the castle. At the northwest corner I felt commanded to look up, which I did to see, some 30 feet above my head, the spider which was now life-sized and completely red flexing in her web. After maybe a half minute the vision began to fade. The next day I realized that I had been given a totemic gift that would direct my relation to poetry.

As I continued to struggle to get Vallejo’s complex and complicated Spanish into English, I increasingly had the feeling that I was struggling more with a man than with a text and that the struggle was a matter of my becoming or failing to become a poet.

During this period I translated every afternoon in a downtown Kyoto coffee shop called Yorunomado (= Night Window). In “The Duende” section of “The Book of Yorunomado” (the only poem I completed to any real satisfaction while living in Japan), I envisioned myself as a kind of angel-less Jacob wrestling with a figure who possessed a language the meaning of which I was attempting to wrest away. I lose the struggle and find myself on a seppuku platform in medieval Japan, being commanded by Vallejo (now playing the role of an overlord) to disembowel myself. I do so, cutting the ties to my “given life” and releasing a daemon named Yorunomado who, until that point (my vision told me) had been chained to an altar in my solar plexus. Thus at this point the fruits of my struggle with Vallejo were not a successful literary translation but an imaginative advance in which a third figure emerged from my intercourse with the text. Thus death and regeneration = seppuku and the birth of Yorunomado, or a breakthrough into what might be called sacramental existence. Years later, I noted Hans Peter Duerr writing in Dreamtime: “Only a person who had seen his ‘animal part’; who had ‘died’, could consciously live in culture.”

In “Self As Selva,” a poem from a new manuscript called “Penetralia,” I write: “Self as engine as well as brimming circumference. Self as one’s mind after & before birth: differentiated identity & the undifferentiated lower levels where specters from humanity’s past still dwell. . . . Self as selva, a liana matrix of twintwisted lingo.”

SK: Shifting the movement I proposed into a psychological topography is helpful, I think, in drawing it into conversation with a wider range of ideas. Partly here I’m interested in the extent to which a poet’s work might remain confined to a self-conscious criticality, positively or negatively, without descending into the undifferentiated lower levels of the self, or conversely, a poet’s work might be entirely devoted to such a descent, without situating that descent in relation to a social reality. I’m interested in the mechanisms by which you remain committed and keep yourself committed to or attentive to both of these realms. This is, I think, ultimately a question about your creative practice. In the example you’ve just mentioned, your engagement with Vallejo’s work as a translator, alongside your poetic attempts to write your way out of Indiana, seems to have provoked a visionary experience, which itself became foundational in your ongoing work. I don’t want to reduce this complex moment and experience to some kind of formula for poetry, but I’m wondering to what extent this kind of priming is necessary for sustaining a creative life in poetry. I’d also like to hear more about what you mean by the phrase “sacramental existence”?

CE: I find your first question, asking the extent to which a poet might confine his work to self-conscious criticality without engaging the self, impossible to answer. “The extent to which” is the rub, and without a particular poet (or dimension of my own work) to look at, I don’t know how to take on your question. If you have a poet you feel is an example of this situation, I will try to respond, assuming I am familiar with the work. You then wonder about the mechanisms by which I engage both realms. I draw a blank with the word “mechanisms.” Finally you ask another “to what extent” question regarding my spider vision followed by my self-destruction and the birthing of Yorunomado. As I think I wrote, these two events are foundational to what I have been able to accomplish as a poet over the decades. Invented mythical figures like Yorunomado and Niemonjima that are embroiled in the action in my book Coils (1973) complexed some of the autobiographical consternation in that book.

The crucial event in my development after leaving Japan in 1964 was my 1974 discovery of Cro-Magnon cave art in southwestern France. Suddenly, in the spring of 1974 I was completely caught up in the deep past and what possibly was the origin of art as we know it today. This grand transpersonal realm (without a remaining history or language) was about as far away from my Indianapolis adolescence as could be, and as I researched and revisited the painted caves throughout the late 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, this focus released me from my preoccupations with my background as well as my working with Blakean mythic strategies. In many ways, Juniper Fuse is the key book of my career.

By “sacramental existence” I mean to suggest that the birth of Yorunomado enabled me to escape from the tyranny of time into a “spontaneous” creation of myth making. For an instant I was the master of my own death and regeneration and released from the stuffed/empty impasse of the Indiana background. I was in touch with one of the essential functions of myth: the re-entry into Great Time, or sacred Time.

SK: I take your point about the phrase “to what extent.” I’m tiptoeing around a problem in poetry and poetic vocation. I think it’s fair to say that not all poets have a visionary experience of initiation into or confirmation of poetic vocation. In an interview published a few years ago in The Wolf, you remarked: “nearly all of the poetry reviewed, lauded, and prized today, is not the real thing.” Is visionary experience or confirmation required for poetry to be real poetry, as you understand it? Beyond that, could you say a little bit more about the relationship between the foundation of your work in your visionary experiences in Japan and the ways that your research into the painted caves built upon or extended that foundation?

CE: My comments that you quote from The Wolf interview refer mainly to the extent to which “creative writing” (child of the university degree writing programs) is replacing poetry. Of course there is no ultimate criteria for what makes a poet engaging, but my experience has been that with a few marvelous exceptions like Rimbaud or Lautréamont it involves a self-taught apprenticeship based on a study of a few chosen masters in American poetry and hopefully a few masters in international poetries. My fantasy is that the young writer would learn more crouched by the banks of the Amazon with a knapsack full of books than he would in creative writing workshops.

The kind of experiences I had in Kyoto in the early ’60s are not a requirement for someone becoming a poet. They were a product of my own background and fix, and everyone has a unique situation in this regard. I think you know that my range of interest in contemporary poetry is wide and varied. I published Charles Simic and Jorie Graham in Sulfur magazine as well as Charles Bernstein and Rachel Blau DuPlessis. I suppose a careful reader could find links between the poetries of the poets I have translated, but poets such as Vladimir Holan, Bei Dao, César Vallejo and Antonin Artaud represent as many differences as things in common.

My crucial perception concerning the origin and elaboration of Upper Paleolithic cave imagery is carefully set forth on p. xvi in Juniper Fuse. Briefly, it concerns my intuition (underscored by my reading of James Hillman’s The Dream and the Underworld) that such images were motivated by a crisis in which Cro-Magnon people began to separate the animal out of their about-to-be human heads and to project it onto cave walls (as well as onto a variety of portable tools and weapons made out of the animals themselves).

There is a ten-year interval between my initial Yorunomado transformation and my perception concerning the separating out of the animal as a formative function of Cro-Magnon imagination. In both of these cases, separated by thousands of years of culture dynamics, a mysterious intuitive projection involved the need to transform one’s present situation into a larger, more mind-engaging possibility. I transformed a Kyoto coffee-shop into an imaginal daemon; in the Cro-Magnon situation (which goes back as far as 32,000 years), and in a way that can be considered proto-shamanic (another link), a blank cave wall, under minimal lighting, became a kind of dancing ground for a hand gripping a piece of charcoal.

SK: I love your fantasy of a poet on the banks of the Amazon with a backpack full of books. You’ve also mentioned the reading and research that guided and informed your writing on the painted caves in particular. I also know that you read other types of research materials when working on your translations. How does research feed your work? Is it essential to it or supplemental to it?

CE: As the first poet to do what Charles Olson referred to as “a saturation job” on Upper Paleolithic cave art, I was really starting from scratch, I had to make myself responsible for much of what archeologists had written about them as well as to study other thinkers who might help me support my own evolving point of view. Thus I not only read the work of the Abbes Breuil and Glory, Annette Laming, Andre and Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, S. Giedion, Max Raphael, Paolo Graziosi, Alexander Marshack, Jean Clottes, Margaret W. Conkey, and Paul Bahn, I also read C.G. Jung, Sandor Ferenczi, Geza Roheim, Mikhail Bakhtin, Weston La Barre, Charles Olson, N.O. Brown, Kenneth Grant, James Hillman, Hans Peter Duerr, Barbara MacLeod, and Maxine Sheets-Johnstone. I also sought to match my pluralistic approach with varying styles. Juniper Fuse is of poetry, prose poetry, essays, lectures, notes, dreams and visual reproductions.

Translation, research-wise, was a different matter. The two years that I lived in Kyoto (1962-1964) I visited the poet, editor, and translator, Cid Corman, at The Muse Coffee Shop, in downtown Kyoto, in the evening once a week. Corman was then editing the third series of his magazine origin, and he already had an impressive track record as a translator of Catullus, Rimbaud, Basho, Rilke, Ungaretti, Char, Montale, Daumal, Daive, Ponge, Celan, and Artaud. Corman is one of the great poetry translators of our time. Before talking at The Muse with Cid about translation, I thought the goal was to take a literal draft and interpret everything that was not acceptable English. By interpret I mean: to monkey with words, phrases, punctuation, line breaks, even stanza breaks, turning the literal into something that was not an original poem in English but—and here is the rub—something that because of the liberties taken was also not faithful to the original itself. Ben Belitt’s Neruda versions or Robert Lowell’s Imitations come to mind as interpretative translations. Corman taught me to respect the original at every point, to check everything (including words I thought I knew), to research arcane and archaic words, and to invent English words for coined words—in other words, to aim for a translation that was absolutely accurate and up to the performance level of the original. Corman’s translation information was so valuable that I have never felt a need to seek out translation theories.

I began to translate Vallejo while a student at Indiana University in the late 1950s and completed The Complete Poetry of Cesar Vallejo (University of California Press, 2007), some 45 years later. During this nearly life-long saga, given the difficulties in rendering Vallejo accurately, certain co-translators were invaluable in my work: I owe an enormous gratitude to Maureen Ahern, Americo Ferrari, Jose Rubia Barcia, Efrain Kristal, and Jose Cerna-Bazan.

The current collection of my Essential Poetry includes 223 poems from over 1000 published poems from this fifty-year period. There are seventy pages of notes following the poems and reading these notes will give the reader a sense of the research I have done in writing some of my own poems. In particular I would like to point out the four pages of notes, based on Weston La Barre’s Muelos: A Stone Age Superstition about Sexuality, for the poem “Navel of the Moon,” and the 4 pages of notes, based on Sandor Ferenczi’s Thalassa: A Theory of Genitality, for the poem “Thalassa Variations.” James Hillman’s writings have been especially valuable for my poetry. In A Sulfur Anthology, based on the magazine I founded and edited from 1981 to 2000, published in the fall 2015 by Wesleyan University Press, the reader will find my interview discussion with Hillman on psychology and poetry.

SK: In your “triadic dialogue with Paul Hoover and Maxine Chernoff” published in The Price of Experience, you remark that, “working on poems is mainly working on self, the subconscious as warp, consciousness as woof, while keeping self positioned in the actual world.” How is your research related to this notion of poetry as work on the self?

CE: Good question. Here is one example of the way my research can relate to writing poems that relate to the self.

Over the years I have pondered Sandor Ferenczi’s Thalassa: A Theory of Genitality, and wondered how his unique argument might shed light on the origin of image-making. In brief, Ferenczi proposes that the whole of life is determined by a tendency to return to the womb. Equating the process of birth with the transition of animal life from water to land, he links coitus to what he calls “thalassal regression”: “the longing for sea-life from which man emerged in primeval times.” He explains what he means by an “attempt to return to the mother’s womb”—and thus to the oceanic womb of life itself—in the following way:

If we now survey the evolution of sexuality from the thumb-sucking of the infant through the self-love of genital onanism to the heterosexual act of coitus, and keep in mind the complicated identifications of the ego with the penis and with the sexual secretion, we arrive at the conclusion that the purpose of this whole evolution, therefore the purpose likewise of the sex act, can be none other than an attempt at the beginning clumsy and fumbling, then more consciously purposive, and finally in part successful—to return to the mother’s womb, where there is no painful disharmony between ego and environment as characterize existence in the external world. The sex act achieves this transitory regression in a three-fold manner: the whole organism attains the goal by purely hallucinatory means, somewhat as in sleep; the penis, with which the organism as a whole has identified itself, attains it partially or symbolically, while only the sexual secretion possesses the prerogative, as representative of the ego and its narcissistic double, the genital, of attaining in reality to the womb of the mother.

In one respect, “Thalassa Variations” is a compression of, and variation on, Ferenczi’s argument.

To my knowledge, N.O. Brown is the only writer to have heretofore assimilated Ferenczi’s theory of genitality into a larger dimension including creativity. In Love’s Body, Brown even acknowledges the Upper Paleolithic caves as the places in which history begins. Like Ferenczi, Brown is a Freudian, and while he views the Upper Paleolithic caves as the first labyrinths, he fails to reflect on what seems to be their most distinctive characteristic: they were not merely wandering places, or even dancing enclosures, but the sites for some of the earliest image-making. Following Ferenczi, Brown views genitality as ultimately ungratifying, in effect a trap. Ferenczi’s proposal that we desire to return to the womb and obviously cannot, in Brown’s terms, becomes the limitation he calls “genital organization.”

Since Brown also draws upon William Blake’s vision of four mental states potentially operative in humanity, it may be useful to point out that from a Blakean viewpoint, to be confined to “genital organization” is to be arrested at the third level of mental expansion (see the poem, “The Crystal Cabinet”), or to be in the State of Beulah. In other words, Blake appears to mean that those who settle for sexual gratification alone are not fully, in his terms, “human.” For Blake, there is a fourth state, the State of Eden, in which imagination is engaged and realized, and in which art that we might call great is created. Blake’s image for this state is fire in love with fire (from which Yeats undoubtedly got his image of creative unity: the dancer as unidentifiable apart from the dance). While there may be a temporary “gratification of desire” between two people in the State of Beulah, in the State of Eden the other vanishes, and for the individual to avoid plunging into the lowest State—the State of Ulro, in which one is simply unimaginatively stuck with oneself—one must practice a sort of imaginative androgynity called art. While Brown does not include cave art in his discussion of the labyrinth, he does view coitus as a fallen metaphor for poetry.

Were Blake alive today, I am confident that he would make the connection I am about to make: the womb that cannot be returned to à la Ferenczi was imaginatively re-entered when Cro-Magnon crawled into a cave and drew, painted or sculpted an image. I conjecture that one impulse for going into the cave was orgasm itself, which flooded the mind with fantasy material that sought a fulfillment beyond survival concerns. Image-making, then, can be seen as the attempt to unblock the paradoxical male impasse of genital expression, or, in my poem, it is what the belling deer image “says” to its Cro-Magnon maker on his back in that cul-de-sac in Le Portel: “Image is / the imprint of uncontainable omega, / life’s twin.” In the same stanza, I attempted to draw upon the Freudian/Ferenczian theory of the sexual stages of development, working with the possibility that from childhood on, oral, anal, and genital formations are incorporated in image-making, which for the creative individual becomes a kind of fourth dimension (or State à la Blake) that includes the earlier three and pushes beyond.

SK: Great example. The poem in this case is a variation on motifs and ideas drawn from Ferenczi, Brown, and Blake, in dialogue with images from Le Portel as well as your personal—in fact intimate—life with Caryl. It’s psychoanalysis, poetry, the Paleolithic record, and personal experience fused together. I also recall that the word variation carries musical reference for you as well: from the impact of your discovery of variations on melody in jazz music. And then too I know that “Thalassa Variations” is a kind of variation on a theme you explored in a previous poem, “This I Call Holding You” (published in What She Means, 1978). Can you talk about the persistence of themes or topics in your work? Is there a difference for you between a recurrent theme and a re-written one?

CE: In a poem called “The Tjurunga” (Anticline, p. 17; see the Note on pp. 75-76 for the meaning of this word), I propose a kind of complex mobile made up of the authors, mythological figures and acts, whose shifting combinations undermined and reoriented my life during my poetic apprenticeship in Kyoto in the early 1960s. At a remove now of some fifty years I also see these forces as a kind of GPS constantly “recalculating” as they closed and opened door after door. Making up the mobile in this poem were: Coatlicue (the Aztec idol with the sacrificed woman Coatlicue inside her), sub-incision (the primeval rite conferring androgynity upon its male participant), Bud Powell, César Vallejo, and the bird-headed man (from the Shaft in Lascaux). After this list of powers, I wrote:

These nouns are also nodes in a constellation called

Clayton’s Tjurunga. The struts are threads

in a web. There is a life blood flowing through

these threads. Coatlicue flows into Bud Powell,

César Vallejo into sub-incision. The bird-headed man

floats right below

the pregnant spider

centered in the Tjurunga

When I was sixteen years old, I taped two quarters to an order form in Downbeat magazine and mailed it off for a 45 RPM recording with Lennie Tristano’s “I Surrender Dear” on one side, Bud Powell’s “Tea for Two” on the other. I listened to the Powell piece again and again trying to grasp the difference between the song line and what Powell was doing to and with it. Somehow an idea vaguely made its way through: you don’t have to play somebody else’s melody—you can improvise (how?), make up your own tune! WOW—really? You mean I don’t have to repeat my parents? I don’t have to “play their melody” for the rest of my life?

You ask if there is, for me, a difference between a recurrent theme and a re-written one. There is, but both are operative in my body of work: early inspirational figures such as Powell, Hart Crane, and Chaim Soutine return in poems from time to time (there are three pieces on Powell, six on Crane, and six on Soutine). As they do so, they are recast into current preoccupations and challenges. Crane’s metaphoric shifts evoke improvisational moves in bebop or strokes in a de Kooning painting of the 1960s. Reading Crane is like watching colored fragments in a turned kaleidoscope slip into new symmetries, then rearrange again. “New thresholds, new anatomies!” indeed!

I saw my first Soutine in 1963 in the Ohara Museum of Art, Kurushiki, Japan, Hanging Duck, painted in Paris around 1925. Seeing this painting was so riveting that I recall nothing else in the museum. It was a hybrid fusion, at once a flayed man hung from a pulpy wrist and flailing, with gorgeous white wings attached to his leg stumps—and a gem-like putrescent bird, snagged by one leg, in an underworld filled with bird-beaked monsters and zooming gushes of blood color and sky-blue paint.

My life has been blessed with a number of dear painter friends including William Paden, Leon Golub, and Nora Jaffe. Over the decades I have written pieces about all of them, and with Paden (Brother Stones, 1968) and Jaffe (Realignment, 1974) I co-authored books. Over a period of some 35 years I composed seven poems, reviews and essays on the paintings of Leon Golub. The most ambitious piece is a poem called “Monumental,” which I assembled for Leon’s public memorial program at the Cooper Union’s Great Hall in NYC, 2005.

Including the pieces based on Ice Age cave art, I have written over 150 poems on art and artists. In a 2005 statement for deep THERMAL, a book I co-authored with the painter Mary Heebner, I wrote: “I am interested in what I see in paintings as well as what the paintings see in me. I found in certain Mary Heebner watercolors a resonating psychic stimulation and attempted to improvise on the words, narrative nodes and associational “chains” they flushed forth.” For many years, the following words of Baudelaire, from “the Salon of 1846,” have inspired such workings: “I sincerely believe that the best criticism is that which is both amusing and poetic: not a cold, mathematical criticism which, on the pretext of explaining everything, has neither love nor hate, and voluntarily strips itself of every shred of temperament. But, seeing that a fine picture is nature reflected by an artist, the criticism which I approve will be that picture reflected by an intelligent and sensitive mind. Thus the best account of a picture may well be a sonnet or an elegy.”

At the base of these recurrent workings on and with musicians and painters are some thoughts elaborated in a 2009 poem “Inner Parliaments” (published in Anticline):

I

is an arm with a hand.

How did I first announce self?

In the Upper Paleolithic, it placed its hand on a cave wall,

spat red ochre around the hand, withdrew the hand,

leaving an I-negative on the wall.

Is what we now call art an elaboration of this I-negative,

Kafka’s “What is laid upon us to accomplish is the negative,

the positive is already given”?

SK: Considering this, another phrase of yours springs to mind: “the name encanyoned river.” Your body of work reads as an extended and shifting kaleidoscope of dialogues, considerations, encounters, and engagements with words, ideas, images, places, objects and experiences. Aside from the remark from Baudelaire that you mention, are there other poets or writers whose ekphrastic writing particularly inspired your ongoing engagement with the visual arts? I suppose I’m thinking in particular of Artaud and Henri Michaux as two poets whose poetry has been meaningful to you and who also wrote compellingly about the visual arts.

CE: My earliest recollections of involvement with the visual arts goes back to reading the “funnies” in daily Indianapolis newspapers, collecting comic books, and drawing my own cartoon strips. When I was around ten years old, my mother offered an art student from John Herron School of Art in Indianapolis a free dinner and a couple of dollars to give me and my pal Jack Wilson weekly cartoon lessons. I vaguely recall one of my cartoons winning a prize at some contest in a downtown department store. In my junior and senior years at Shortridge High School I took some figure drawing classes and did quite well in them. I sketched a drawing of a hobo who had been paid to pose that my mother put up on our living room wall for many years. I think I might have become a painter had there been a more intense local art atmosphere to inspire me at the time.

My mother also arranged for me to take piano lessons from a neighborhood piano teacher when I was six years old and the lessons continued up through my teenage years when I studied with the concert pianist Ozan Marsh. I was playing Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude” on one hand, and on the other, starting to hang out at local blues and jazz clubs, such as The Surf Club on West 16th Street where one Saturday afternoon Wes Montgomery invited me to sit in with his band. In my last response to your queries, I cited my discovery of Bud Powell when I was sixteen, and a couple years later, in the summer of 1953, I rode out to Los Angeles with a friend and studied briefly with Bud’s brother Richie, and Marty Paitch. A few years later, while studying Philosophy at Indiana University I discovered poetry moreorless on my own, and through my meeting Jack and Ruth Hirschman and Mary Ellen Solt was put in touch with the writings of the Beats and Black Mountain-associated poets, as well as many of the great 20th century European poets.

You ask if there were any particular poets who inspired my now lifelong involvement with ekphrastic writing. My earliest memory of writing a poem about a painting was an occasion in one of Sam Yellen’s creative writing classes when he assigned us to compose a poem about a painting. I chose Picasso’s “Guernica” and went ahead to write a second poem on Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.” The Bosch poem was published in The College Art Journal, one of my first publications. Earlier, I mentioned my discovery of Soutine in Japan in 1963, and I think it was his paintings that made me really want to engage paintings and artists in poetry. None of the poets I was reading in the ’60s and ’70s had a compelling ekphrastic focus, or if they did, I was not aware of it.

Michaux and Artaud: I have written two pieces on Michaux, and I will let my opening salvo at the beginning of “Michaux. 1956” (1956 was his big mescaline-oriented year) represent that connection:

There is in Michaux an emergent face/non-face always in formation. Call it “face before birth.” Call it our thingness making faces. Call it tree bole or toadstool spirits, anima mundi snout, awash in ephemerality, anti-anatomical, the mask of absence, watercolor by a blind child, half-disintegrated faces of souls in Hades pressing about the painter Ulysses-Michaux as, over his blood trench of ink, he converses with his hermaphroditic muse . . .

Artaud is an even more complex figure. I was introduced to him in 1965 in the Hirschman Artaud Anthology which Jack sent me when Barbara and I were living in Lima, Peru. Over the decades I have written nine pieces on Artaud, or out of, into, Artaud. For someone who has yet to meet Artaud, I highly recommend the four books, all in print, that the English essayist/novelist Stephen Barber has written on this writer. Antonin Artaud is one of the greatest examples in art of the imaginative retrieval of a life that was beyond repair. What he ultimately accomplished should bear a torch through the dark nights of all our souls. Given the new perspectives on his writings and drawings that he created in what may now be considered his second major period—from his regeneration in the Rodez asylum in 1945 to his death outside of Paris in 1948—I have focused on that second period in the translations that I have done of his poetry and prose: Watchfiends & Rack Screams, unfortunately published by Exact Change Press in 1995 which has not paid me royalties for a number of years and refuses to release rights to my translation so that it can be republished with new translations in an even more ample presentation of Artaud’s accomplishments during this late period.

SK: Earlier in this conversation you observed that the most crucial event for your development as a poet after leaving Japan was your discovery of the Paleolithic painted caves. I don’t want to argue with that observation. We’ve also just been talking about your wider engagement with the visual arts and music. I know that civic engagement is also important to you. When did you first become civically or politically aware and engaged?

CE: I began to become politically aware in Lima, Peru, 1965. I was shocked by the extent of terrible poverty there and began to wander the barriadas (slum neighborhoods) in an attempt to really get what they were under my skin. In my book Walks, published in 1967, “Walk VI” focuses on one of these excursions. At the same time, I was working for the Peruvian North American Culture Institute, editing a new bilingual magazine I called Quena (after the one-holed Peruvian flute). I had gone to the Institute looking for work teaching English as a second language as my wife (who was quite pregnant) and I had no money when we arrived. We had gone to Lima because I wanted to inspect the worksheets for Vallejo’s never-completed Poemas humanos which were in the Vallejo widow’s possession there.

Anyway, I included in the first some 300 page first issue of the magazine, five poems by Javier Heraud (translated by Paul Blackburn) that he had written before going to Cuba several years earlier. Before that trip, Heraud was apolitical and the poems Paul translated were old-fashioned nature poems. However, while in Cuba, Heraud became politicized and when he returned to Peru in 1963 as a member of the Ejercito de Liberacion National, he was shot by local police while drifting in a dugout near Puerto Maldonado. His death as a would-be guerilla created a scandal in Lima and because the Institute, it turned out, was receiving funding from the USIS, the American Ambassador in Lima (who had been shown the Quena manuscript by my concerned boss at the Institute) said that the Heraud translations could not appear in a publication sponsored by the Institute. I refused to remove the Heraud poems and was fired.

While all of this was going on, I discovered that a number of Peruvian poets who I had become acquainted with thought I was an American spy because I was employed by the Institute. So I guess you could say that I was thrust into a new and complex political situation through going to Peru and through assembling this first issue of Quena with Heraud in it.

When Barbara, the recently-born Matthew, and I moved to NYC in 1966 I discovered that my old painter friends Leon Golub and Irving Petlin were directors of an ad hoc organization “Artists Against the War” and I quickly became in charge of the poets participating in demonstrations throughout the city.

SK: Picking up the notion of a “constellation” from the passage you quoted a moment ago from your poem The Tjurunga, wherein the “nouns are also nodes in a constellation called / Clayton’s Tjurunga.” A constellation is distinct from a series or some other form of linear or logical arrangement. I see the notion as being related to your take on the “anatomy” in Blake via Northrop Frye. Are you self-conscious in your approach to assembling or arranging the constellation of materials at the level of the poem or at the level of a collection of poems? A piece like Notes from a Visit to Le Tuc D’Audoubert, for example, shifts registers in one way, while, on the other hand, Juniper Fuse, as a book, constellates elements in, it seems to me, a different way.

CE: “Notes on a Visit to Le Tuc d’Audoubert” is an anatomy, in Northrop Frye’s sense, in as much as it is, let us say, a structural make-up of a poetic organism with contrasting parts, such as poetry, prose poetry, paragraphs, and visual “punctuation.” In my note on this poem in Juniper Fuse, I mention that years later I realized that these “Notes” were the nuclear form for a book that would become an amplification of its multiple genres. Included in this amplification would be photographs, drawings, extensive commentary, chronologies, and such invented daemons as Kashkaniraqmi, Atlementheneira, and Savolathersilonighcock, joining the earlier Yorunomado and Niemonjima.

Juniper Fuse is also a constellation, or an assemblage, that is loosely chronological with the earliest pieces written in 1978 and final sections composed in 2002. I say “loosely” because this chronological arrangement is not always followed. When I was working out the final Table of Contents I saw that certain pieces written in different periods belonged together so I broke up a strict chronological order to take that sense of the book into consideration.

All of my books, over the decades, are, in general, chronological, allowing the above-described exception various degrees of play.

While living in Kyoto (1962-1964) I spent a great deal of time breaking my head over Blake’s “Prophetic Books.” Titles such as “The Book of Yorunomado” are based on Blake having called his shorter Prophecies “Books,” like “The Book of Ahania” and “The Book of Los.” Gary Snyder writes somewhere that when he came unannounced to visit me one afternoon he found me asleep on the tatami in my workroom and left after deciding not to wake me up. I had actually passed out that day while reading Blake’s “Book of Urizen.”

These “books” that I was composing in Kyoto (and later in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1964-65), were sections of a Blake-inspired long poem to be called “The Tsuruginomiya Regeneration” (the title coming from the name of the Shinto shrine across the road from the Ibuki home where Barbara and I were living in 1963-64). I started this poem initially as a marriage celebration for Paul and Sara Blackburn but given the extent to which I was confused and lost finding my way in poetry (and attempting to translate Vallejo’s Poemas humanos) the “Regeneration” quickly became a Blakean-nuanced quagmire. In the early 1970s I put several of the most coherent “Regeneration” “books” together with some recent poems to compose Coils (1973).

SK: As a long-time reader of your work, I find the relationship between The Tsuruginomiya Regeneration and Coils a compelling conundrum. You’ve mentioned that you published a great deal of the Regeneration in journals and chapbooks. Was there something about attempting to bring the pieces together into a single collection that brought out aspects of the individual sections that you felt didn’t work or what it something related to the collection as such? I guess I’m wondering about the difference between writing a successful poem and bringing poems together as a successful collection. In this context though, I also recall a remark of yours from an interview originally published in Atropos, later collected in Antiphonal Swing, wherein you said that you didn’t like much of what you wrote between 1966 and 1970, citing a shift in your habits of editing and revising your work before during and after that period.

CE: Each “Book” or section of “The Tsuruginomiya Regeneration” seemed to be the beginning of a new long poem. I was lost, and unable to discover an all-over plan I could write into. I was way too haunted by Blake’s abandoned manuscript of “The Four Zoas” (originally called “Vala”), and my attempts to ingest his long poems (or “Prophecies”) at that time was probably a mistake as their mythic turmoil mainly muddled my personal turmoil rather than suggesting a way that I might proceed in coming to terms with my poetic apprenticeship. Two of the “Books” that I kept as part of Coils, “The Book of Yorunomado,” and “The Book of Niemonjima” have some very good writing in them with the Blakean influence helping me to go beyond what I would otherwise been able to write.

I never again attempted a long poem, or epic. I have done a few extended pieces, like “Tavern of the Scarlet Bagpipe” (forty-two pages), my imaginative investigation of the great and profoundly mysterious “Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch, “Anatomy of the Night” (fifty-six pages), an anatomy of sorts, made up poetry, prose, and quoted passages from the work of Roheim, Reich, Hillman, Alvarez, Cioran, Djuna Barnes, and James Hamilton-Paterson, as well as some material from my own writing between 1983 and 2011, and “The Moistinsplendor” (forty-eight pages), an LSD-inspired rant, about which I have written: “On one level the poem is a struggle to think against erasure. At the moment I would seem to focus on something, the drug kicked it into a kaleidoscopic maze. My experience with LSD was that it operated mentally like the amusement park ride called the loop-the-loop. I found myself constantly wildly swinging between what appeared to be an imaginative insight and having the insight pulled inside out and being slapped in the face with it. When a line suddenly looked peculiar or dumb I would immediately write down the next thing that came to mind. There was no revision. I had the feeling, as peculiar as it may sound, that by drinking wine while I wrote that I was grounding myself and keeping the LSD from whirling me into a lockjaw abyss.”

As for the period between 1966 and 1970: including translations and chapbooks I published twelve books during this period. I think the best of my own work are probably Walks, The House of Okumura, Indiana, and The House of Ibuki. I have included twenty-two poems from these four collections in The Essential Poetry 1960-2015 (Black Widow Press). That is not much, in my case, for four years of work, and it mainly shows that at that time I was often unable to edit my poems into precise, imaginative structures or, from a present point of view, to determine between a poem that worked and one that did not. The first book in which I hit the stride that I like to think I have maintained with increasing acuity ever since is the 1981 Hades In Manganese.

SK: Some of your most recent poetry strikes me as among the strongest of your career. I’m particularly thinking of An Anatomy of the Night and The Jointure, among other recent pieces. And I’m thinking in particular of the fluidity with which you shift directions, depths, and registers in these writings, covering an enormous range of thought and human feeling. Despite the range of content, the writing is, I think, unmistakably yours not only because it represents your ongoing thought but also because of the way that the materials come together or perhaps rather intersect with or overlay and impact one another. The work seems to have inverted the figure you advanced a moment ago: if the early epic failed to come together for lack of a structure into which you could write, the current work seems to emerge from a core of concern that is all of a piece. All or nearly all of your more recent work seems to be part of an unfolding, expansive epic.

From reading other interviews and remarks you’ve made about your writing process, I know that your relationship to editing has changed over the course of your career. How large an impact has your editing process had on your work and on your recent work in particular?

CE: Over the past few years it has become increasingly difficult for me to engage material for a possible poem and then to realize the evolution of this material in a way that I find satisfactory. Most of the sixty-six poems in my latest completed manuscript, “Penetralia” (to be published by Black Widow Press in 2016) were completed between 2008 and 2015 and the last half-dozen, which include “The Jointure,” required many drafts to realize. I think the sixteen-page “The Jointure” must have close to 150 worksheets.

Such difficulties lead me to the following considerations: In my 40s, 50s, and 60s, I often found myself in a contrapuntal relationship to what occurred in writing: I would begin a poem with an idea of an impulse to engage particular material and the writing proceeded via thematic perceptions as well as spontaneous dream-like input which thematic material appeared to flush out. Such was not like dreaming awake. Rather, it was as if my intentions in a poem beckoned to my subconscious which like a helpful handmaiden offered to contribute material that sometimes contradicted, sometimes improvised, upon what my conscious mind thought the poem was about. A good example of what I am attempting to identify here is the 1989 “At the Speed of Wine,” an 11 page descriptive vision of drinking in a New York City bar with Hart Crane. I got the idea for writing such a poem by reflecting on my co-translation of Vladimir Holan’s magnificent “A Night with Hamlet” in which the speaker (Holan) imaginatively engages a special night visitor (a phantasmagoric one-armed crazed Hamlet who appears to the poet in his Prague apartment). My poem is also shadowed by Ulysses’ conversation with Tiresias in Book XIII of The Odyssey. I mention these influences as background stimulation; I don’t think most readers would read my poem and think of Holan or Homer.

Anyway, there is only one draft for “At the Speed of Wine.” I sat down after a nice dinner with some good red wine and wrote the poem in about three hours without stopping. I showed it to Caryl the next morning who “edited” it. She eliminated a few repetitions and clarified some images, thus sharpening the focus without doing much rewriting.

I can’t compose like that anymore. Maybe all poets have an arsenal which is a combination of the given and the developed and which finally feels almost cleaned out. I say “almost” because as I approached what felt like an emptying in 2012-2014 I moved into a kind of summational “old age” voicing in which I attempted to wrest from my situation material that could be thought of as imagined while standing in my own smoking gate.

SK: “At the Speed of Wine” is a rather astonishing precipitate of three hours writing! Set beside “An Anatomy of the Night” it does demonstrate a certain internalization and condensation of its wide-ranging materials: the dialogue with Crane compacting engagements with Holan, Homer, Hamlet, Artaud, Van Gogh, Caravaggio, etc. In the later work, following some of the language we’ve been using, the materials are constellated more loosely, though no less pointedly. Perhaps this is consistent with a kind of “late style.”

There’s a line in “At the Speed of Wine” that stands out for me in this context: “The book is always late; the book is, in fact, belatedness.” You’ve been writing poetry for more than fifty years, translating poetry that reaches back to the beginnings of modern verse, and writing through the visual arts, including most significantly your writing on the painted caves, that, in your phrase for Juniper Fuse, “includes the earliest nights and days of soul-making.” I’m wondering how you think of time in your writing—in the act of writing but also in the process of editing your poetry and books of poetry. For example, some of your poems carry indications of dates and places related, presumably, to their composition, others do not. Is poetry bound to the moment in which it is written or does it have some other relationship to time?

CE: The appearance, in 1963, of Yorunomado, birthed out of my gut in seppuku, was my initial thrust into sacramental existence. It was also a furtive attempt to recover what might be called Great Time, or mythic time, not only a break with profane duration but the attempt to engage the paradisiac, primordial situation: time without a past.

However, most of my early writing, given the thoughtlessness in my adolescence and initial manhood, was involved with my own personal history. Here I am thinking of such pieces as “Letter to Cesar Calvo,” “Hand,” “Sunday Afternoon,” “The Bridge at the Mayan Pass,” “Still-life with Fraternity” and “Tomb of Donald Duck.” Today I am uncomfortable with all of those pieces but I included them in The Essential Poetry because they show me attempting to realize my own provincial, family history.

The poems I have written on Western art and Western artists seem to me today to be a mix of striving in time and release into some of the aspects of Great Time e.g., “Soutine’s Lapis” is on one level very engrossed with Chaim Soutine’s painting the stinking hanging fowl he secured from Paris slaughterhouses and the extraordinary otherworldly creatures he turned them into on some of his canvases. On one level, regardless of the subject matter, artistic creation (including poetry) evokes, regardless of the subject (or in the case of a Pollock, the non-subject), the attempt to overcome time. Relative to creation, publication (and exhibition) is always belated, though I guess one could argue that at the very point the poem or painting is completed, it becomes belated to the creative act itself.

As you note in your most appropriate question here, the discovery of the Ice Age painted caves of southwestern France, in the spring of 1974, was huge and very lucky for me, for suddenly I was confronted with an art that had no accessible historical basis including any access to the language of the makers. And to call it “art” is tricky, for surely it is imbedded with utilitarian, magical, and occult prototypes that, primitive art aside, historical art has for the most part never engaged. As someone considerably concerned with my own background I was suddenly faced with a making, the context of which was nearly completely inaccessible. And to put it this way is not to complain! It was the biggest gift in my life, for it put me in touch with a genuine back wall, the earliest days and nights of soul-making. And that feeling of having been put in contact with something that might be called the original of art was extraordinarily encouraging and gave me the sense that I could possibly be part of something beyond what modern poetry with at best a hazy sense of a Greek “back wall” had envisioned.

SK: Does this engagement with the paradisiac, primordial situation—time without a past—figure in your creative practice as a translator or in your prose writing?

CE: As for poets who I have translated: Aimé Césaire’s poetry in the 1948 Solar Throat Slashed is permeated by elements of a cosmological myth, involving a self-immolating solar divinity who generates the processes of destruction and renewal. As the speaker says in the powerful “At the Locks of the Void,”

It is I who sing with a voice still caught up in the babbling of elements. It is sweet to be a piece of wood a cork a drop of water in the torrential waters of the end and of the new beginning. It is sweet to doze off in the shattered heart of things.

Or in the same poem:

I await the boiling. I await the baptism of sperm. I await the wingbeat of the great seminal albatross supposed to make a new man of me. I await the immense tap, the vertiginous slap that shall consecrate me as a knight of a plutonian order. I await in the depths of my pores the sacred intrusion of the benediction.

While Antonin Artaud cannot be called a shaman proper, there is a shamanic resemblance binding his life and work. When I hold up Artaud’s image, I see shamanic elements in it, like a black root-work suspended, coagulated yet unstable, in liquid. For example, while in the asylum of Rodez in 1945-46, he bore, out of his heart, a new progeny of warrior-daughters who became his assaulted messengers and saviors. He used the block of wood that Dr. Delmas placed in his room like a drum. He also had a “bridge” which he wrote was located between his anus and sex, and it was upon that bridge that he claimed he was murdered by God who pounced on him in order to sack his poetry. Spitting and a falsetto voice were also present. Of course what is missing in such a shamanic scenario is a community. Artaud is a Kafka man, put through a profound and transfiguring ritual while finding out, stage by stage, that it no longer counts. He is a shaman in a nightmare in which all the supporting input from a community that appreciates the shaman’s death and transformation as an aspect of its own wholeness is, instead, handed over to mockers who revile the novice at each stage of his initiation.

Juniper Fuse is of course my attempt to link poetry to what may be its origin, or back wall, in the some two dozen or so hybrid figures to be found in Upper Paleolithic cave imagery. Since over half of the writing in this book is in prose, or prose poetry, such would constitute a positive response to your question. I think that some of the strongest support for such thinking is to be found in the five-part “Cosmogonic Collage” that concludes the book. Section One, “The Dive,” examines a myth that several scholars have proposed can be traced back to the last Ice Age. I link a shaman-creator diving to the bottom of the sea as an animal or bird in order to bring up creational material to a Cro-Magnon artist descending to the depths of a cave and mixing cave water with red ochre or black manganese to draw animals on stone walls, very ancient indications of what we today call the creative act. In Section Two I describe what I call a Black Goddess stone tree only partially emerged from stalactites, fissures and folds. Possibly as early as 25,000 B.P. Cro-Magnon people identified and marked this proto-World Tree. And in Section Five, I describe a forked blade from Le Placard dated roughly between 18,000 and 16,000 B.P. that has a woman’s groin carved in the base that appears to be projecting an ithyphallic blade. To put it idiomatically, this is a hole that grows into a pole. These three examples strike me as some of the most unique and cogent examples of very early imaginal workings of time without a past.

SK: These are extremely potent examples of this problematic. However in posing the question I was wondering more specifically about the act of translation or the act of writing prose, as to whether or not you could access this primordial experience through translation or through writing prose, or if, on the other hand, translation and prose writing function in distinct ways for you in terms of your creative practice.

CE: In my response to your fifth question I commented on my approach to translation via time spent with Cid Corman in Kyoto in the early 1960s. While translating writers like Vallejo, Artaud, and Césaire is a challenging linguistic adventure and the deepest way I know of to read them, since I do not take creative liberties in this work I don’t think my practice engages anything like primordial experience. I think the closest thing to imaginal depth in this case would be some poems I have written off Artaud in which his mind stirred my mind in one example to engage what I called “black paradise.”

That poem is in Anticline.

I included only a few prose poems in the Essential Poetry because most of them do not show me at my best. The prose I am most satisfied with involves pieces on writers or painters I admire (Paul Blackburn, Gary Snyder, Charles Olson, Artaud, Leon Golub, Chaim Soutine, Paul Celan, Allen Ginsberg, Ron Padgett, Judith Scott, Nancy Spero, and Hart Crane, for example) or on aspects of Upper Paleolithic cave art (which of course unlike writing on contemporary poets drops me into the abyss of origins and Great Time). Some of the prose on Blackburn, Soutine and Crane engages creative imagination (in contrast to critically examining what a particular author has written). The Olson dream presented on p. 262 of Juniper Fuse portrays the poet passing from personal consciousness into collective consciousness or the realm of creature souls.

It occurs to me that some of the Horrah Pornoff “Homunula” workings, in exploring an invented mind, might be thought of as spontaneous creations with an invented temporal duration, though they of course are presented as poems.

Perhaps you have something in mind here that I have not picked up. If so, please write about this and I will try to respond.

SK: This gets to the notion I had in mind—essentially about the difference between writing poetry and translating poetry in your creative life. In my own experience as a translator, the confrontation with the text of another, across the chasms of time, place and cultural context, has often been quite a challenging and humbling psychological experience, akin to being lost in a forest. We’ve already spoken of your early struggles to bring Vallejo’s voice in particular over into English. We didn’t mention the fact that the process was ongoing, after your initial publications of his work in the late 1960s, through several new versions of the work, culminating in the publication of the Complete Poetry in 2007. You’re involved in a similar exercise now with Aimé Césaire’s poetry, which you’ve also been translating since the mid-1960s. Do you get closer to the core of the text with each subsequent translation? Do you find that there any certainties in translation?

CE: In regard to the first part of your question concerning getting closer to the core of a text: over a period of thirty-nine years (1968-2007), I completed three published versions of César Vallejo’s Human Poems, his most substantial collection. During this period, while writing my own poetry on a nearly daily basis, and editing two literary magazines (for a total of twenty-four years), I became an increasingly focused writer. I think that each new version I did of this Vallejo book became more accurate and precise than earlier ones, and if this is so, the reasons for such involve not only my own growth as a writer, my increasing familiarity with Vallejo’s psyche and the Spanish language, but my improved agility to process the help I received from two co-translators (Octavio Corvalan with Vallejo’s Spanish Civil War poems and Jose Rubia Barcia with the Human Poems) along with the half dozen other people who made useful suggestions to my versions that we went over together.

Other than a little collection of early Aimé Césaire poems I translated with my old friend Denis Kelly in Bloomington, 1966, I have again had two splendid co-translators with my ongoing attention to his writing: Annette Smith who I worked with off and on for a decade (our collaboration producing translations of the 1956 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, The Collected Poetry of Aimé Césaire, and Lyric & Narrative Poetry (1946-1982) and A. James Arnold who I began to work with around 2008. Arnold and I have published two Césaire collections (Solar Throat Slashed and The Original 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), and have recently completed a version of The Complete Poetry of Aimé Césaire which Wesleyan University Press will publish in 2016. While I still respect Annette’s and my Césaire work I have become a better translator than when I worked with her in the 1980s and James Arnold is the leading Césaire scholar most probably in the world. Thus it has made sense for Arnold and I to retranslate the earlier Eshleman/Smith versions as well as the rest of Césaire’s poetry.

It is also important to note that I began to translate Vallejo during my poetic apprenticeship, and I often worked on him in Kyoto when I was lost or blocked with my own poems. By the time I began to work on Césaire, I had fifteen years with Vallejo under my belt and a pretty good sense of what I wanted to accomplish in my own poetry.

As for certainties in translation: That is a slippery question! One reason that I have worked with co-translators is that as a translator-poet I have had to undermine my impulse to embellish or simply alter the original when it seemed flat or, especially in Vallejo’s case, when it was densely ambiguous. Working with the people I mention above has brought me as close to certainty as I could come. When one is translating a living author who is available for questioning (I made three trips to Paris to ask Césaire questions about arcane and coined words in the early 1980s), the chances of certainty in the work theoretically improve. However, here I must acknowledge that when I was translating the poetry of Michel Deguy, with Deguy, daily, in Paris in the early 1980s, I discovered that from time to time he would make up a meaning for a word we were discussing that, were I to accept it, would appear simply as a mistranslation! So maybe it is better here to say that while a translator can court certainty he can never fall asleep with complete satisfaction in her arms.

SK: Working with these co-translators to bring the voices of other poets into the reservoirs of English suggests a kind of creative community at work that seems to transcend any kind of “anxiety of influence” in Harold Bloom’s sense of that phrase. The notion also evokes for me the dedication of The Price of Experience to Robert Kelly and Jerome Rothenberg, as “fellow Argonauts,” which I take to suggest reference to a creative community among you. Aside from the co-translators you’ve mentioned, who have been your closest collaborators?

CE: While I do not think you could call her a collaborator in the sense that we wrote poems together, Caryl, my wife, who edited my work from roughly 1973 to 2008, is the closest to a collaborator. I acknowledge her work at the beginning of the seventy-two pages of notes that end The Essential Poetry. I would show Caryl drafts of poems and she would make comments that often led to rewriting or rethinking particular moves. All in all, she sharpened my focus and caught a number of clichés and repetitions. What I have been able to accomplish as a poet is profoundly in debt to her.

In 1996 I sent a copy of Nora’s Roar to Adrienne Rich who I had not had any contact with for decades (I had a brief acquaintance with her in NYC in the late 1960s but lost contact with her in the early 1970s after her husband committed suicide and she became a lesbian who for some years had little or no contact with men). I got a wonderful letter from her after she read my elegy for Nora (who had been one of her oldest friends), and this started up a regular correspondence that ended a few weeks before Adrienne’s death in 2012. We must have exchanged around 300 letters and many of them contain, on both our parts, poems in progress that the other poet would comment on. Adrienne had a very sharp eye and her criticisms of my work mainly entailed objections to what she felt were rhetorical flourishes. I suspect in this regard she helped me more than I helped her as the poems she sent me I think had already been through some revision.

Several author friends have made useful comments on aspects of my work: Cid Corman on early Vallejo versions in Kyoto; Paul Blackburn on some poems in the late 1960s, and Ron Padgett, whose recent comments on drafts of An Anatomy of the Night and “Velmar’s Lemon” (still unpublished) were extremely useful in helping me to finish this work.

I should also acknowledge your comments on certain poems to include in The Essential Poetry that I had, at the time you wrote me, left out of this evolving manuscript. I reread the poems you listed and put some of them in.

But in terms of real collaboration, a one-to-one writing relationship, I think I have only experienced this with Annette Smith, José Rubia Barcia, and James Arnold in Césaire and Vallejo translating.

I referred to Robert Kelly and Jerome Rothenberg as “fellow Argonauts” because we have been friends in poetry and in our personal lives since the early 1960s. And also because I feel that our three bodies of work are one of the most original and accomplished artistic contributions of our generation. The territory that our three bodies of work covers is, in my opinion, spectacular. I feel that the three of us have continued to push on and out, beyond those who influenced us, into the previously uncharted.

SK: That push, on and out, as you say, beyond your—and Kelly’s and Rothenberg’s—influences, itself strikes me as a defining, even constitutive element of all three bodies of work, and of others’ besides, but of your moment, if that word can be allowed, in poetry and really in thought and ethics as well. There’s this engagement with language and life in the work that is personal and historical, psychological and cultural, and profoundly restless and searching, probing. For all the politically correct lip service to “diversity” in contemporary writing, my sense is that that search, that push on and out, has become all too rare in poetry today. Perhaps I am missing something, but I am reminded of the beginning of the foreword Adrienne Rich wrote for your book Companion Spider, where she wrote: “There is very little around today . . . that possesses the depth and substance of this book . . . the accumulated prose-work of a poet and translator who has gone more deeply into his art, its process and demands, than any modern American poet since Robert Duncan or Muriel Rukeyser.” It’s a marvelous encomium, of course but also true. Perhaps poetry as the scholar’s art (Wallace Stevens’ remark that you have quoted at times) seems out of fashion today. Do you share this sense of contemporary poetry? Are you aware of poets today whose writing continues this approach to poetry?

CE: If Paul Hoover’s Postmodern American Poetry (the second edition, 2013) is representative of the new, I would say that the university degree writing programs have had a very detrimental effect on a number of aspects of poetry as I know and respect it. Flarf is simply mediocre writing and Conceptualism is aestheticized plagiarism. As I have mentioned or at least implied earlier in our interview, I do not think one learns how to become a poet in a degree writing workshop where one spends most of one’s attention listening to the opinions of other students who are also, at best, novices. Academically speaking, I think one builds up one’s literary arsenal by discovering for oneself, on one’s own, the essential American poets to study, of the past and of one’s own generation and then by reading all of their writing. Such research must be amplified by learning reading skills in at least one foreign language along with reading some of the poets of that language in the original, and reading translations of them, with the aim of teaching oneself how to critique translations.

I should add that besides Robert Kelly and Jerome Rothenberg, I think that Michael McClure, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Andrew Joron, Rae Armantrout, Will Alexander, John Olson, and Sarah Fox (to name the poets who first come to mind) are doing genuinely innovative writing today.

As for the Wallace Steven’s statement on poetry as the scholar’s art (from his book Adagia), I understand it to mean two possible things: that poetry may be the art that appeals most to scholars, and that poets can incorporate scholarly research without lessening the intuitive drive it takes to write commanding poetry. Basho, André Breton, Octavio Paz, and José Lezama Lima are four non-American poets who come to mind here. I think of translation as on one level scholarly activity, and I think one can make a similar case for editing a literary journal.

SK: Do you think that the digital revolution (the internet but also digital printing) has had any meaningful impact on the ways that poetry is written and read today? Have “little” magazines, broadsides and chapbooks been replaced by digital forms of publication?

CE: There is a curious comparable increase in graduate degree writing programs and internet blogs and e-zines. I don’t have any exact figures here but one explanation for this double increase may be the following: an e-zine is much easier to set up and to operate than, say, a magazine like Sulfur which cost near the end of its run in 2000, around $6000 per issue to produce, pay contributors, and mail, with roughly 800 subscribers. Over the magazine’s eighteen-year run, we had various distributors, none of which really made any money for the magazine (and one, Truck, when it went bankrupt owed the magazine $2400 none of which we ever received). Jacket, an e-zine from Australia, other than the cost of computer equipment and monthly server fees, had no other costs that I am aware of, and must be read by thousands of people online. I once submitted to Jacket a trilogue with Paul Hoover and Maxine Chernoff about the various magazines the three of us had edited, and it appeared the next day. Thus for young writers with Masters or PHD Degrees in creative writing it is much, much simpler, and inexpensive, to start up a e-zine or blog than a 250 page magazine like Sulfur.

While I imagine that an e-zine with Sulfur’s range and depth could be produced, I am not aware of any. Nor am I aware of any print magazines today that can be compared to Sulfur.

You ask if the digital revolution has had any impact on the way that poetry is written today. Hard to really tell, but I suspect that given its tie-in with the degree writing programs it has. Both Flarf and Conceptual Poetry are primarily 21st century phenomena, along with other cyberpoetries. And I must acknowledge that were I a senior at Indiana University today, knowing no more than I knew then, I might be tempted to enroll in a Masters or PHD creative writing program. Thus educating myself on my own, with a lot of books and a few correspondents (and getting out of USA to experience the foreign cultures of Mexico, Japan, and Peru) can be seen as my response to the young writer’s situation in my era.

On the other hand, for all I know (since at eighty I have more-or-less stopped reading first collections of poetry and hardly read any magazines online or off) there may be young writers out there doing what I did in the late 1950s. From time to time a young poet who does not appear to be in a writing degree program, sends me some poems to read. Some of them are genuinely interesting. The poets I mentioned in the last post as doing innovative writing today, while for the most part several generations younger than me, came into poetry in the non-digital world.

SK: Can you say a little bit about what you mean by the word “negation” in the last paragraph of the essay “An Alchemist with One Eye on Fire” where you wrote: “I continue to regard poetry as a form in which the realities of the spirit can be tested by critical intelligence, a form in which the blackness of the heart of man can be confronted, in which affirmation is only viable when it survives repeated immersions in negation—in short, a form that can be made responsible for all that the poet knows about himself as his world.”

CE: My comment on “negation” is derived from a statement by Paul Tillich: “A life process is the more powerful, the more non-being it can include in its self-affirmation without being destroyed by it.” As well as from the Kafka quotation I mentioned earlier. In contrast to the kind of research I did on Ice Age cave imagery which I thought of as affirming the oldest creative core of humankind, a civil or political focus turns the writer into a kind of moving target in evasion of those forces society uses to disarticulate him: self-censorship as well as editorial censorship: the shying away from materials that disturb a predictable and aesthetically-acceptable response.