Ellen Levy

The MIT Press ($54.95)

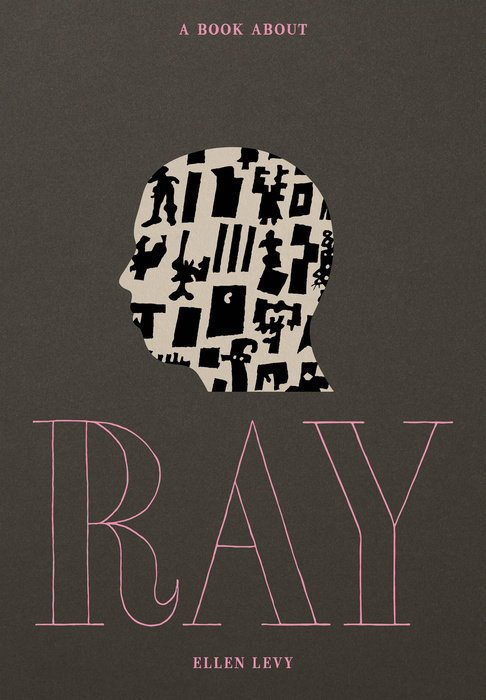

By far the most complete framing of coyote trickster artist Ray Johnson (1927-1995) to date, Ellen Levy’s A Book About Ray engages with the work of the artist on his own terms, or at least as approximate to them as possible. Given the often abrasive opacity of Johnson’s (non-)engagement with curators, critics, and scholars, this can’t have been easy. Levy herself describes her book as “not, or not exactly, a life story. This is an art story.” Some may think they know that story from John W. Walter’s 2002 documentary How to Draw a Bunny, however that film portrayed Johnson mainly as a mail art collagist, adding to the quizzical and cryptic sense of Johnson that had already given him cult-like art celebrity status. Levy’s book reveals more of Johnson’s work and investigates the overall drive behind it.

A Book About Ray progresses in roughly chronological order, though it also freely cycles forward and backward in time via artistic statements on recurring motifs and themes found in Johnson’s work. After early years of artistic output in Detroit, Johnson attended the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the late 1940s, and there he flourished—especially as a favored talent in Bauhaus artist Josef Albers’s classes, dutifully attentive to “the clear, wise, and constructive ideas” behind “the relational nature of color” Albers championed. That aptitude led to a November 1947 cover of the magazine Interiors by Johnson consisting of three rows of colored upright rectangular boxes full of polka-dots of varying size and color along with one row of rectangular boxes with parallel stripes of various colors running across them. His painting Calm Center (1951), a grid of squares each containing a plethora of colored lines that offer “variations on the square,” is also very much in the Albers vein, save that the square at center is solid black.

Also at Black Mountain, Johnson established friendships with fellow student artists such as Ruth Asawa, who he heard speak of “the Taoism philosophy of nothing ness [sic] being everything-ness”; Johnson realized, “I feel that way.” It was at the college as well that he took up with a teacher, beginning the longest romantic relationship of his life with the married sculptor Richard Lippold (it ended in 1974). Leaving the school, Johnson followed Lippold to New York City; in the summer of 1951, they took up residency downtown “in the shadow of the Williamsburg bridge,” occupying individual studio spaces alongside Morton Feldman and John Cage (each of whom had also spent time at Black Mountain). Thus, from a young age Johnson was very much in the thick of the burgeoning New York City art scene, where he would remain even at a distance after moving out to the North Shore of Long Island in 1969.

In addition to the cover of Interiors, Johnson designed now-iconic book covers for New Directions, including William Carlos Williams’s In the American Grain and Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations; the Rimbaud cover utilized a portrait of the poet, which Johnson would continue recycling by using it in several collages. In the New York art scene, Johnson knew Andy Warhol and there are significant associations between Warhol’s work and his own. This is particularly true of his use of portraits: Johnson often drew upon images of iconic cultural figures such as Marilyn Monroe, and in fact, pre-dates Warhol’s use of such images with works from 1956-58 featuring James Dean collaged with the Lucky Strikes cigarettes logo and Elvis covered in red wash and bleeding tears.

Levy reports how “Ray and Andy were known to shop together sometimes for movie stills and magazines.” Johnson, however, did not share in Warhol’s loftier ambitions. His portraits of these stars “got progressively grungier” and always remained small; “made to be held in hand by their recipients,” they “speak volubly of the artist’s hand” in their making, as opposed to Warhol’s industrial, oversized mass screen prints. And as weird as Warhol’s reputation holds him to be, Johnson was even further afield. Factory participant Billy Name demonstrates this with a telling comparison, saying “Andy was still like a person” whereas “Ray wasn’t a person. He was a collage or a sculpture. A living sculpture, you know. He was Ray Johnson’s creation.” Art for and on art’s terms alone was always Johnson’s sole intention.

At the center of Johnson’s work are mutually unachievable co-existing wishes. As Levy describes, “Ray Johnson wanted to be famous, and he wanted to remain unknown, and he clung to the belief, whose absurdity he relished, that it was possible to be both at once.” Johnson enjoyed the dilemma of always choosing to have things every and any way he desired, regardless of the lasting impact upon himself, his work, or anything else. Nothing mattered less to him than what many others valued most—critical acknowledgement, financial success, and media attention. Not that he didn’t pay attention to such matters; he simply refused to directly pursue or be enticed by them. The introduction of these concerns into any exchange with Johnson regarding his work would immediately sour further discussion. Yet Johnson nevertheless would send unsolicited correspondence to gallery owners and museum curators, and he had shows and would lecture at art schools during residencies. To be seen and not seen. Chameleon. Enigma. Artist shapeshifter. Johnson was all of these.

In his collages, Johnson constantly interchanged his own set of iconic figures and related symbols, creating exchanges of identity and associated possible meanings. As he announces, “One can pretend to be someone one is not. Children’s play. I’ll be you and you be me. Be my valentine.” There is implicit intimacy behind his work, only it is not necessarily personal: instead Ray Johnson was “a person who lived for art to a point where he convinced others, and perhaps at times even convinced himself, that any aspect of his life that could not be assimilated into his art should not be considered part of the Ray Johnson story.”

Johnson was “a creature and creator of networks,” and one of his first was what became known as the New York Correspondence School. Within what became a vast interlocking web, Johnson openly handed over the reins of creation to others, asking the recipients of collages and other materials he mailed them to work on them and then send them on to others he named, putting all involved on the spot. As Levy asserts, “To correspond with Ray Johnson was to assume the role of artist.” The fact that he was continually looking for opportunities to diminish showing his hand in any artistic activity brought tension into his correspondence, however. Artist-performer Jill Johnston states it plainly: “I didn’t correspond with Ray because he scared me. I found him kind of intense.”

Levy tracks each of the several altering forms Johnson’s artworks took shape in. Among the earliest series were the Moticos, which had the appearance of being “paper scraps” yet were “made things, artworks of a kind” that held meaning beyond any literal, physical manifestation. As he stated: “perhaps you are the moticos.” Johnson would send these works (which easily slipped into envelopes) to Correspondence School participants, and as a result, many of them ended up in the hands of art collectors and dealers without his knowledge, let alone any control over sales or financial compensation. Another important work was A Book About Death, “one of his strangest and most enigmatic projects. The ‘book,’ never constituted as such, consists of thirteen unbound prints designed one by one between 1963 and 1965, each mailed out as it emerged to various correspondents.”

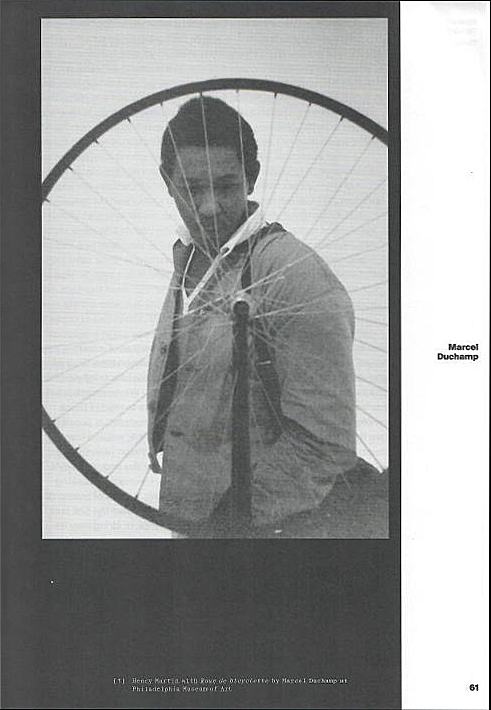

Later came the bunnies—“his signature icon a crudely drawn rabbit-head”—issued with a seven-step set of drawing instructions under the heading “New York Correspondance School”; Levy notes that the “simplicity of its rendering suggests that the icon is rooted in the Duchampian ethic that held that everyone and anyone could be, in fact already is, an artist.” Near the end of Johnson’s life arrived the Move Stars, a series of images forming an “assemblage, laid out on the ground, of graphic images of bunnies and other icons,” each panel-like piece being “32 inches high. And vary from 7 ½ to 8 inches wide,” which Johnson arranged at various suburban locales around his local Long Island home, photographing them with dispensable one-click cameras. These were not seen by many until long after Johnson’s death, when “in 2019, Joel Smith, curator of photography at the Morgan Library, searched them out and went through them all and calculated that the artist had run through 137 cameras, from which he had printed over five thousand images.”

There’s not the space here to cover every aspect of Johnson’s work that Levy brings to light. Her book includes ample color images, scattered as if collaged at times across the pages, and care has been taken to have the book resemble an art object itself, an experimental risk which pays off. Levy’s eye-opening A Book About Ray mirrors Johnson’s elusive disappearances even as it highlights what made this unique artist the phenomenon he was.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025