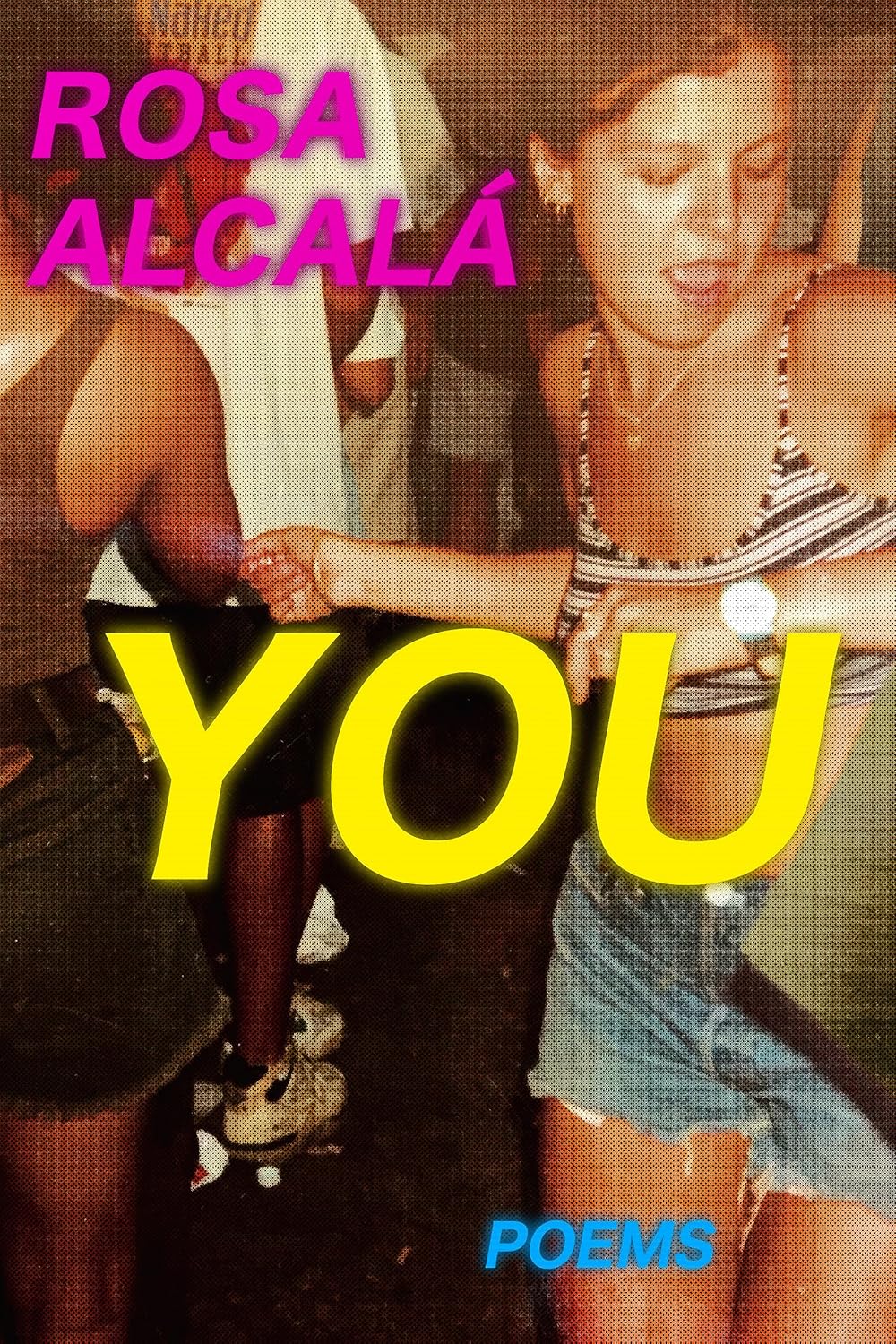

Rosa Alcalá

Coffee House Press ($17.95)

Rosa Alcalá’s fourth poetry collection is a thrilling masterpiece filled with prose poems that challenge and disturb as they dig deep into the terrors that women face. Throughout, readers are also invited to contemplate the complexities of voice and perspective in literature.

An introductory piece outlines where fear begins for women and girls and prepares readers for the unconventional approach of the text. Alcalá makes an important decision to rely upon the pronoun “you” to tell her story. At first it may seem that this allows her to remain one step removed from the painful memories she shares; “Isn’t the second person a form of hiding?” Alcalá asks. But the poems that follow fully explore the slippery magic of the pronoun “you”—how it can alternate between standing in for the reader, the author, and an ever-shifting cast of characters.

Alcalá tells us from the start that “I was trying to write a book about my mother,” but “that in the absence of her I mothered myself all over again with worry, / which is how I mother.” In this light, the “you” in every poem has the potential to be the poet, her mother, her daughter, another woman, or even womanhood itself, and sometimes more than one of these at the same time. Alcalá seeks to bear witness to the violence committed against women, but “being my own witness was itself a risk. How can / I see events unfolding when the body is completely symptomatic / of other bodies, including / its own.” She continues:

The problem with memory is that only words can re-create it for others.

Each word its own past and desire

for a future.

Each word, each sentence, a fragment.

And how do you untangle from the telling the speaker’s motives?

Later in the book, in “A Girl Like You,” the poet uses the second person to address both herself and a person she wrote about for her first real assignment as a journalist: a thirteen-year-old girl “whose tender body was discovered next to the Cuban bodega where your mother would send you for bread.” In the second half of the poem, the dead girl talks back, taking Alcalá to task for using the tragedy to further her career:

You want to know who did it, how it could have happened to me and not you. You want to weave it into a cross to protect the door to your daughter’s room. Or worse, for a poem. . . . Was your first intention to make my murder elegiac? Remember when you couldn’t pronounce that word correctly, when others saw you as you were, a girl who knew so little but elbowed herself to the front to be heard.

Nearly every poem contains horrific gut punches as well as sentences of such sublime beauty that you may temporarily forget their disturbing subject matter. Alcalá uses her fear as a map, seeking “narrative logic to order the / mess of memory” while never losing her faith in language’s potential to express the ineffable and reveal the truth about our lives. In this bold and innovative work, she has achieved her stated goal to “leave my daughter this book as manual, as heirloom; like my mother’s wedding dress in the unreachable part of my closet, both glamorous / /and warning.” Charles Olson once proclaimed that poems are “high energy constructs”; Alcalá’s YOU contains writing so powerful it may cause your heart to combust.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2024-2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025