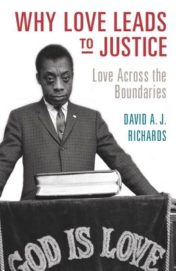

David A.J. Richards

David A.J. Richards

Cambridge University Press ($30)

by Brian Gilmore

I began reading David A.J. Richards’s book Why Love Leads to Justice the week before the Pulse Club Massacre in Orlando, Florida. Forty-nine patrons lost their lives and fifty-three more were wounded when a homophobic gunman opened fire in the club as it was closing on June 11, 2016. It has been described as the worst mass shooting in U.S. history, though this is likely inaccurate. Nevertheless, it was a tragedy beyond comprehension, one that highlights the need for important books such as this.

Richards, openly gay for decades and a law professor, focuses on the poisonous idea of patriarchy so prevalent and destructive in the West. Through the lives of several prominent gay men and women who must navigate a society governed by oppressive love concepts, Richards argues for something new. In his world, the entrenched “Love Laws” of the West—those advanced by patriarchy, sexism, racism, hate, and homophobia—can be challenged and discredited effectively.

Richards undertakes this task by writing about the lives and the work of figures such as writer James Baldwin, poet W.H. Auden, composer Benjamin Britten, and First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt. He sets up his detailed discussion of these lives and social ideals with an opening section that explains patriarchy, which he sees as the key to understanding our backwards society. Richards writes that it “supports and . . . enforces the antidemocratic structural injustices of extreme religious intolerance, racism, sexism, and homophobia.” In addition, patriarchy “elevates some men over other men and all men over women.” The father in the family structure holds “authority” over all affairs of daily life, and it is this troubling arrangement that is challenged in Richards’ book. These early passages are important because as Richards eventually notes, patriarchy has created a “personal and political psychology that supports” the injustices it seeks to uphold in society.

The fact that individuals in positions of power have embraced patriarchy has also resulted in embedding it into our laws and political systems. Thus, it is no accident that anti-LGBT laws continue to be championed by so many in the name of religion or social custom, just as slavery, Jim Crow, and other anti-black laws were once part of the nation’s legal structure. It is also no surprise, according to Richards, that violence as witnessed in Orlando remains a part of our patriarchal society, because people such as the club goers that evening challenge the patriarchal hierarchy by breaking the “Love Laws” laid out for them.

Richards’ portraits of gay men, their relationships, and their personal struggles is impressive. Auden, the celebrated British poet, is depicted as a proud gay man but also one who is tormented, having embraced the very homophobia that he has successfully challenged. The chapter on Christopher Isherwood, Auden’s lover and also a celebrated writer, is just as rich. Born into a prestigious British family where he was the son of a mythic British military officer killed in World War I, Isherwood rejects the typical masculine life of a war hero only to embrace his late father’s other side—his love of liberal arts and humanities. Father is more than a military myth in death; he is a man who can love. Christopher, the son, as a result of this influence, moves to Berlin at Auden’s behest and becomes a writer.

It is no surprise that James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin have their own chapters here. Both emerged during the civil rights period and both lived lives as openly gay men who challenged America’s puritanical patriarchy. While Rustin was reared in the world of “anti-patriarchal Quakerism,” Baldwin’s development as an essential voice on injustice in America came about because he was immersed in the patriarchal world of his stepfather’s Baptist church in Harlem. While Richards notes that both men are mostly known for their “ethical resistance” to white supremacy and its manifestations in society, they too broke the “Love Laws” Richards keeps at the center of the book. Both did so in their relationships with men and Baldwin does so in his writings as well, in particular his novels like Giovanni’s Room.

Richards devotes a chapter to three women who led low-key personal lives as lesbians: Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Mead, and Ruth Benedict. Once again, Richards’ selection of these particular women is important not just for who they were and how they conducted their lives, but also for their work that contributed to the advancement of humanity outside and beyond the normal patriarchal constrictions. Roosevelt’s relationship with journalist Lorena Hickok, not widely known by the general population, is in itself quite a revelation here.

At the end of Why Love Leads to Justice, Richards again explains why more books of this nature must emerge. “As we have seen, again and again, what holds in place some of the structural injustices of our world (anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, and homophobia) are the Love Laws—the series of written and unwritten rules that enforce patriarchy.” Richards has given us a book that resists those laws and showcases the lives of people that did so as well.