Kiriti Sengupta

Illustrated by Rochishnu Sanyal

Hawakal Publishers

by Malashri Lal

Water, that formless, colorless, life-sustaining essence that pervades our being—how does one inscribe it in poetry? In his new collection, Kiriti Sengupta answers in a series of meditations that flow with an enchanting fluidity. The poems dwell on eternal themes such as home, belonging, relationships, and community, but these appear in ephemeral light as though transcending the ordinary and enticing the reader to follow paths of self-discovery.

Reading Water Has Many Colors, I was reminded of these evocative lines in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick: “Consider the subtleness of the sea; how its most dreaded creatures glide under water, unapparent for the most part, and treacherously hidden beneath the loveliest tints of azure.” Here too, the surface calm of controlled structures rests over a subliminal, surging angst, enlivening a crisp duality in which emotions and experiences are transformative, yet the speaker yearns for more change.

This tenuous hold of troubling dualities appears in various ways under Sengupta’s scrutiny. Understandably, the notion of home is questioned: “Dwelling is a slingshot: more it / draws me in, further I fling it way.” While this suggests a perennial odyssey of sorts, Sengupta offers domestic details with roots in cultural practice: “Ma’s healing touch” and a “tiepin from a fiancée” defy the resolution to unhouse oneself from tethers. Who will pay the cost of losing a sense of belonging? Embedded in these poems are complex discourses on location and dislocation, diaspora and homeland, partitions and fragmentations. These mega-events are condensed into haunting lines on memory and forgetting. The brief poem “Ma” is stark—“In the kitchen / her bangles / play a carillon”—yet the sound of that music will echo in the parallel memories of readers.

Sometimes memory travels to a collective space, such as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919—a space marked by bullet holes on a brick wall and the darkness of a well that engulfed hapless women. Revisiting this traumatic event, Sengupta pins his sight on the incongruous item left by a tourist in “The Bottle,” a pensive commentary on a tragic past now pigeonholed into history. The poems “Hibiscus” and “Nostalgia invoke, respectively, the Marxist writer Sukanta Bhattacharya and the educationist Samantak Das, but here, too, disjunctions creep in that elevate historical observation into a poetry of elegiac force.

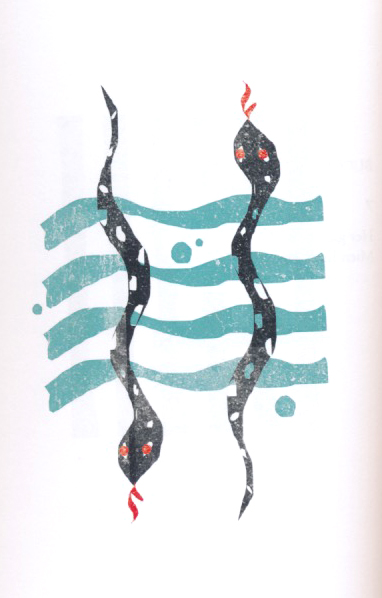

Mythology also gets examined in the pages of Water Has Many Colors, as in the poem “When a Woman Conquers God,” a riff on the Bengali Manasamangal Kavya. In the original story, Manasa, the snake goddess, is both challenged and propitiated by Behula, who wants her dead husband revived after the goddess has destroyed him. Behula succeeds and is upheld as the epitome of wifely devotion, whereas Manasa remains a deity to be feared and propitiated with “the left hand.” Sengupta places this story in the realm of alternative power structures, contrasting ideas of divinity and hierarchies, thereby couching the legend in modern political discourse. Sengupta’s poem “Urvashi” similarly recasts the image of a siren (apsara) figure; Tagore also wrote a lyrical poem about Urvashi, yet in presenting female desire, the famed Nobel Laureate looked towards the domestic ideal, whereas Sengupta’s Behula and Urvashi challenge this, bringing his poems closer to the contemporary idiom of feminist choice.

From myth to the cinema is not such a long journey, especially when one reads about the film diva Rekha and her makeover from the simple “Bhanurekha”; the poet seems quite spellbound in describing her “mystique” and “luminescence.” The actor, director, and talk show host Simi Grewal, clad in white, is another aspect of Bollywood glamour Sengupta engages; it’s a tale of light, image, sound, and “cut” that poetry can mimic in words.

From epics and movies to succinct one-liners, Sengupta suits his poetic form to the subject, just as the folk idiom reminds us that water takes shape from the container in which it is held. The series “Bucolic Bengal” picks out contrasts in nature while hinting that the pastoral idyll is merely spectral; lines such as “kites are born of chimeras” and “mien limns the reality” deliberately pitch elusive, expandable images, stretching the reader’s imagination. On the other hand, the series “Monostich” uses the terse one-line stanza to invoke an inwardness. For example: “What if I am mute or loud?” This poem, “Prayer,” gestures towards multiple meanings; the line may suggest the silent intimacy of grace, but could also allude to mass religiosity.

Water Has Many Colors leaves the reader dazzled by the variety of styles and subjects, an effect reinforced by the captivating art of Rochishnu Sanyal. No line is out of place in the poems or the drawings, and an amazing synergy joins each pairing. The book captures the frenzied pace of modernity yet urges a philosophic acceptance through the enduring image of water. Chronology rolls into timelessness, fragments blend into periodic wholeness, and images float like waves washing up on the shores. This is a celebration of life’s plenitude.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023