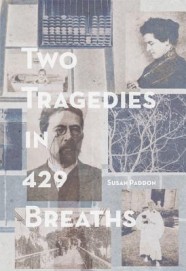

Susan Paddon

Susan Paddon

Brick Books ($20)

by Joseph Ballan

To illustrate the distinctly poetic manner of stitching together apparently distinct experiences, T.S. Eliot suggested that, while the ordinary person “falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes.” Eliot’s choice of illustrative examples is hardly random; if not specific to the life of a writer, they are characteristic of one who lives in the company of books. Susan Paddon’s Two Tragedies in 429 Breaths creates what Eliot would call a “new whole” out of her reading of Anton Chekhov and the experience of her mother’s last months of life, as well as the aftermath of her death. Among other things, Paddon’s debut collection is a record of how experiences of relationships become intertwined with, and felt in light of, experiences of reading, of how books and the real or imagined lives of their authors accompany us.

The relation between Chekhov and death is slightly less arbitrary than that between Spinoza and love. Paddon, who comes to Chekhov by way of her former roommate, a Chekhov enthusiast whom Paddon has left in Paris before the events narrated in the book begin, is especially drawn to the scene of Chekhov’s final years in the Crimean resort town of Yalta, where, ill and plagued by what Paddon calls various “inabilities,” he was cared for by his sister, Maria, at a geographical distance from his young wife, Olga, who for the most part stayed in Moscow. As she returns to Canada to care for her mother—who, like Chekhov, was dying of an illness that affected her ability to breathe and who, like Chekhov, wanted to conceal the full extent of her sickness—Paddon thinks constantly of these three people, and she comes to identify strongly with Maria (also called Masha), imagining her life as a caregiver (“She listens / for breaths, counts them on a wooden abacus, / notes them in a book”) and regarding her as a kind of ministering presence (“Masha, Masha, // watching me tonight . . .).

Not that Paddon’s interest in the Russian short story writer and dramatist is restricted to Chekhov’s biography; his writing permeates the pages of Two Tragedies, sometimes in direct quotation, sometimes more allusively. Along with a biographical précis, the book’s back matter contains explanations, in the fashion of endnotes, of where exactly this or that reference originates in Chekhov’s published or unpublished works. It is unclear what criterion was used to determine which allusions in the poems would be explained in this rather slight “notes” section, and which of the many uncited references would be excluded. Yet one can see just how widely the author has read in the plays, short stories, and letters, as well as in secondary literature on Chekhov. She wears this erudition lightly, so that, in the poems, it feels less like erudition and more like deep familiarity with a literary companion.

The tone of the poems in this book will be familiar to readers of Chekhov, marked as it is by a composure and a restraint that eschews the flashy turn of phrase (metaphors occur infrequently in the book, although these few instances are memorable: the faith of childhood, for example, “was something you could taste at the back of your throat, like metallic blood in the dentist’s chair,” as well as an attunement to the fragile and ephemeral, as in the closing scene of Chekhov’s “Beauties,” which Paddon briefly reimagines at the end of one of her unsent letters to her Paris roommate, the Chekhov enthusiast: “There was melancholy / in the spring air. And in the darkening sky. And in the train car.” There was melancholy, that is, at every point on which the eye might happen to rest.

Loosely bound together by a chronological structure that follows Susan from her return home in April until the months after her mother’s death in August, the individual pieces are formally heterogeneous, comprising letters, invocations to Masha scribbled on various forms of scrap paper, and poems in which the poetic line plays a decisive role, or, especially in the later sections, is virtually nonexistent. From these heterogeneous parts, a whole is fashioned that is, in the end and throughout, extraordinarily—and, in the manner of Chekhov, quietly—moving.