by Paul Dean

by Paul Dean

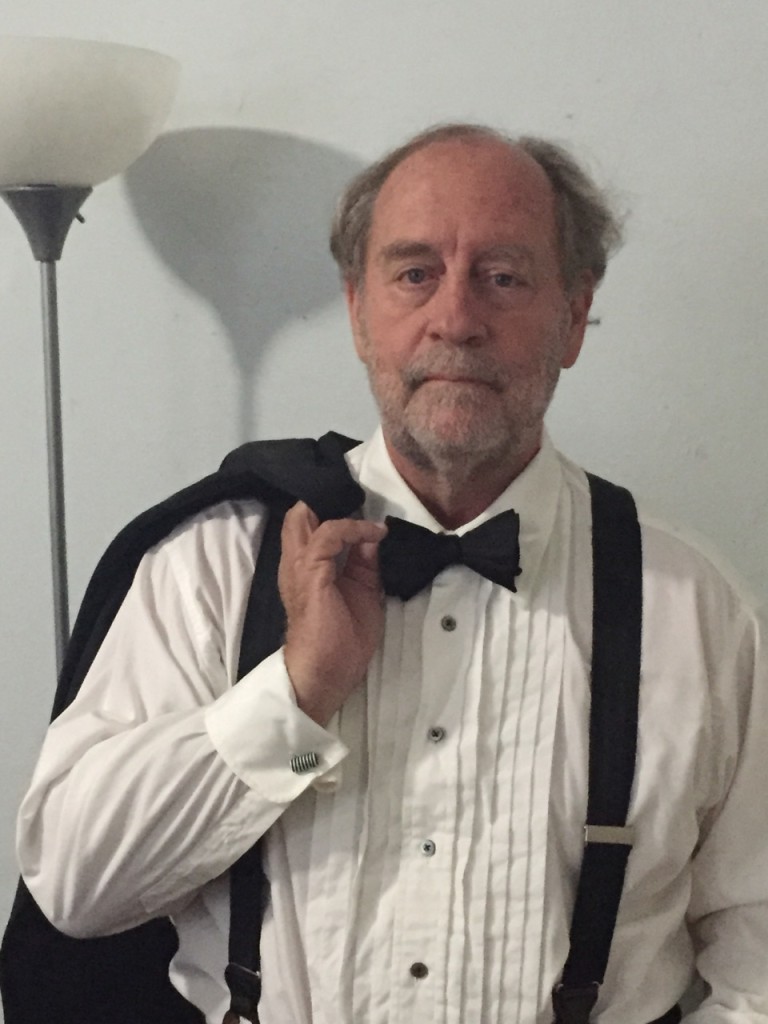

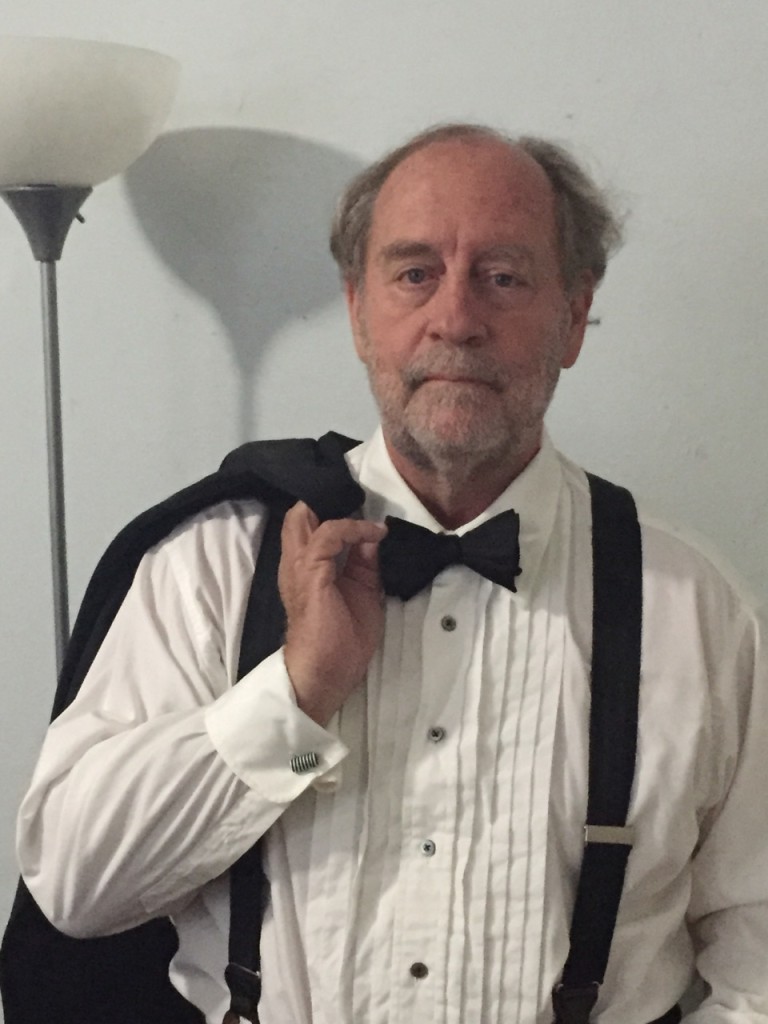

Born and raised in New Orleans, Ralph Adamo is among the many artists who have left that city only to return. For most of his life he has stayed firmly rooted in its presence, raising a family, teaching at the college level, editing, and all the while producing several volumes of poetry, the first two published by Frank Stanford’s and C.D. Wright’s Lost Roads Publishers. He has won several awards for his poetry, including a fellowship from the NEA; he has also worked in various other jobs, including as a television writer and a journalist.

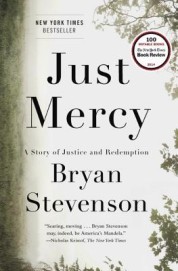

Adamo’s newest book, Ever, (Lavender Ink, $16) came out in 2014, and I saw him read from its pages in the courtyard of the famed Maple Leaf Bar in New Orleans. Adamo’s poems are dreamlike, earthy, raw, and tender at times—especially the ones involving his kids, Jack and Lily. In other instances, Ralph can mesmerize with his language and then surprise you with his ferocity—like the time he told me, “Don't ever be afraid to read a poem; don't ever apologize. You hold that audience like you've got a gun to their heads. You read them a damn poem.” What can you say to that?

In the following interview, we discuss Ever, Stanford, and the mysteries of place and time, among other worthy topics.

Paul Dean: What was it like to grow up in New Orleans and what made you first decide to write? Who were your earliest influences in this regard?

Ralph Adamo: My parents were both readers, and both read to us. I remember my mother reading stories and my father reading us one comic in particular from the Friday funny pages, “The Teeny Weenies,” about little folk who lived in matchboxes and such. There was also always talk in our house, words were part of my upbringing. I read early too, beginning with comic books, which I loved, not just liked. And I loved the library (and later in the suburbs, the bookmobile). The Dr. Doolittle series was a particular favorite, one I have not been able to get my own kids interested in.

Somewhere in about the sixth grade I wrote a poem, and I liked it so much I was hooked, so I kept trying—though not systematically or with anybody reading them. I was by then in the new suburbs of Jefferson parish, but those suburbs were still pretty wild, lots of wooded areas, canals, smoking logs, and snakes. We kids spent a lot of our time in the ’50s and early ’60s walking around in fairly dense wooded areas carrying our BB guns; historical figures like the Green Mountain Boys had some real resonance for us.

I didn’t have any more compelling influences until high school, and even then was not given much of a glimpse of poetry beyond a few predictable American poems. I started writing poems then that now appear to me to be a sort of naturally occurring surrealism (a term I didn’t hear until college). In high school, I found a few people to show my poems to, one slightly older student who also wrote and one teacher who was into literature. I edited our school literary magazine, and gradually I started thinking of myself as “a poet.” By late in high school (the mid-’60s) I began listening to Bob Dylan albums.

These are all elements of what was happening, but I still don’t know what really made me write. I was also very interested in politics and thought of myself as straddling some line between literature and politics, which was as good a way as any to slide into the later ’60s. The images on television from those days—of the civil rights struggle being played out across the South, of the destruction of bodies in the Vietnam War—had a profound effect on me. And of course, in college—Loyola, right here in New Orleans—I met and became close to both Miller Williams (who would move on to the University of Arkansas, with me following) and John William Corrington, who would indulge my taste for erudite talk (his, with me as listener, mostly), sometimes for hours on end.

PD: You mentioned Dylan, and I'm glad you did. I first started to write seriously when I discovered his albums. What resonated with you in Dylan's work? Was it the politics or the poetry itself?

PD: You mentioned Dylan, and I'm glad you did. I first started to write seriously when I discovered his albums. What resonated with you in Dylan's work? Was it the politics or the poetry itself?

RA: Well, both, of course. It pleases me to hear that a young writer like you was also influenced by Dylan. I think he is one of those unavoidable and gigantic influences that we all have to absorb and then resist in our individual assimilations (like Berryman, whom one cannot help but imitate and whom one must not imitate). Dylan’s language is irresistible both as sound and as simple, profound statement. I have no problem identifying his work as some of the great poetry of our time. In fact, the thing that blew my first attempt to get out of grad school with a degree was saying much the same thing in my final exam; my teachers, all of whom were raised on the New Criticism, could not dig it. Anyway, Dylan's work, especially that early stuff, is thoroughly imbued with the politics of the time, and also the residual politics represented in his assimilation of Guthrie, Rodgers, etc.—that is, 1930s radicalism of the sort we lost, so regrettably.

PD: Where do you think the surrealist influence came from in your early writing, especially in how you treat film, landscape, and the city itself?

RA: It may seem odd to say, but I am not really aware of the surrealist influence. It's certainly truer now than it was when I began writing that we are surrounded by surrealist images and ideations; it is pretty much the soup we swim in. Even when I started writing it was pervasive, though we were far less aware of it, and may have not even heard the term. I'm talking about cartoons, songs, some film and television (the sitcom Green Acres, for instance). So a lot of that influence came by way of cultural transmission: The Three Stooges, the Marx Brothers movies, Bullwinkle . . . Where it became conscious and more serious was when I (we) discovered the Latin American poets, and out of sequence, the French poets who'd started it all. Finally, I read Breton's first surrealist manifesto, and all innocence was lost. I began to understand it as a broader philosophical position, not simply a weird way of looking at experience or a set of artistic tools.

Your question includes "the city itself," and that is an interesting thought. I can't claim what Garcia Marquez does—that his surrealism (or magic realism) came from simply observing his milieu—but it's true that New Orleans for a kid growing up offered some wonderful strangeness, like the old Mardi Gras parades and those more innocent crowds who flocked to them; the great diversity that we didn't have a name for then; our peculiar vegetation and the swampscapes around the city. Yeah, that had to have been in my head somewhere.

PD: What made you decide to stay in town to go to college and then eventually pursue creative writing in Arkansas?

RA: Going to college wasn’t the same sort of anxiety-ridden experience it seems to be today. Even so, my experience was probably more random than most. I had not applied to college during high school; only as summer came on did I start looking around, and applied to Loyola without a lot of thought. I signed on as a Poly Sci major, but quickly got bored by the way it was taught. I switched to English, studied under Corrington, and became the first student assistant to the new magazine Williams created, New Orleans Review.

Corrington declined to read my poems, telling me he’d do so once I got them published. Williams was generous, almost eager to mentor me in poetry. For several years this continued as a regular thing—I’d give him a handful of poems, he’d give them back all marked up with suggestions. I’d take some, and move on, more interested in writing new poems than in revising old ones. Eventually, the process became onerous, and I suppose part of my development, as I rebelled against the imposition of his vision, was that my aesthetic became more my own. Memories of that process have influenced the way I approach teaching creative writing; I am less inclined to be a heavy-handed critic, more likely to try to influence students covertly.

There were lots of other things that happened at Loyola—the politics of the late ’60s intruded in a big way. But for me, too, the chance to hear and meet all the writers that Miller and Bill brought to campus (memorably, James Dickey, Shane Stevens, and J. Michael Yates, among others) was world changing, as was the semester when I was selected along with maybe seven other students to be in the first class Walker Percy ever taught. He called the course “The Novel of Alienation,” and the reading list was wonderful, sobering.

The other watershed experience for me involved being first reader for the New Orleans Review—it’s hard to put into words the scope of things I learned in that odd, privileged position. In the late ’60s, too, I began sending poems out and had some success publishing in pretty good places—Shenandoah, The American Scholar, and others. In 1969 I was selected to go to the Breadloaf Writer’s Conference, where I suppose the big thing that happened was the confirmation of my sense of “belonging” in this world of writing, at the same time I was scared of it and put off by it. That’s pretty much continued to be my feeling as a writer.

I met R. S. “Sam” Gwynn there too, a friendship resumed once I got to Arkansas and one that continues. Sam, of course, was a friend of Frank Stanford’s before me, and even hired Frank his first summer there to assist him in some land surveying job, an experience Leon has incorporated in his elegy for Frank, from the story Sam told.

PD: I have to know, if you can remember, what were some of the books from the Percy course that affected you the most?

RA: I remember the whole list! Ellison's Invisible Man had a big impact on me. The theme and characters and writing, of course, but almost more than that, the fact that his protagonist acted, took action, even in his despair. The simplicity and deep cutting quality of The Sun Also Rises comes to mind, and the claustrophobic feeling of Notes from Underground. The breadth of The Sound and the Fury, especially the part where Benji is the narrator. The humor and intensity of Wise Blood. Thinking about it now, I guess what strikes me most about the reading, and our relatively limited discussion of it all, is how much I learned about the act of writing from Percy's almost Zen-like refusal to say much. He was new to teaching, wasn't trying to teach exactly, but whatever he did, it had a lasting effect on me.

Let me mention also the two French books, The Stranger and Nausea. The Stranger is probably the book Percy felt the most about, and that fact communicated itself to us clearly. I remember when I read Percy's Lancelot, I could tell that his book was haunted by The Stranger. Sartre’s Nausea was harder to read and harder to like, and I'm not sure I ever got more than the superficial idea of it, that sense of overwhelming exhaustion.

PD: What was it was like to study with/be around so many interesting people in Arkansas during the ’70's?

RA: Pretty great mostly, with lots of highs and lows. The Vietnam War was dragging on, Nixon was re-elected, and Watergate began to unravel almost right away. There were dark and oppressive clouds everywhere, but my “escape” to the countryside was somehow doubly disorienting. Maybe it was therefore good for my poetry, which flourished in the four years I was there.

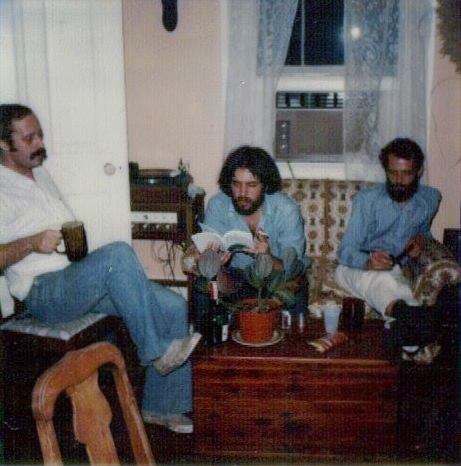

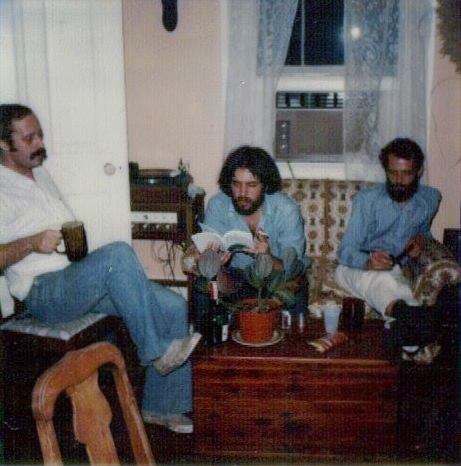

Adamo, Mike Presti (center), and Everette Maddox (right), mid ’70s

There’s no doubt that the real learning for me came not from school, nor from teachers, but from the writers who were there with me as students. Sam was there, very clever and funny and well-read, but because he was married, a little less available than some. My first friends were John Stoss and Leon Stokesbury, with whom I shared a house in my second year there. Stoss was a big farm kid (older by about eight years), insanely prolific, and wildly open to every great influence that came along—someone who early on got surrealism and magic realism and the ancient Chinese poets. Leon was more focused on the immediate poetry scene and world, which he studied hard and knew intimately. He and I spent what seems like a couple of years’ worth of afternoons listening to music stoned, talking and reading poetry, drinking and eating too much. He was obsessive about his own work, constantly making tiny revisions and reading it over and over. I learned most of my early notions of the wider world of poetry from Leon, though there were places he didn’t go—Pound, Olsen, that whole direction of poetry.

Leon had a car; I did not. I probably walked ten miles a day up and down hills. Fayetteville in those days was not the pleasant affluent town it has become. It was still pretty countrified, an old school university town. That whole foreign landscape was a big jolt to my system and probably good for my poetry and development in general. There were others in those first couple of years, like Gary Ligi from New York, who did read Pound and was much more a stranger in the small town South than me. Later Steve Stern, the extraordinary novelist and comic genius, still a close friend. C. D. Wright, so brilliant and gifted and kind and funny. Others I never knew as well like Jack Butler, John Wood, most of the fiction writers. Julia Alvarez came through for a year (or maybe just a semester), quite an exotic presence and very sweet. Like many females who started there (Nancy Harris was one too), she felt less than welcome and moved on. The ethos was a little over-macho; I was one of the few people who hadn’t played football and didn’t give a rat’s ass about it. But Jim Whitehead did, and he was the real heart of the poetry program. Some evenings we’d all be at his house (and he had six or eight kids too); there’d be arm wrestling contests, scrambled eggs smothered in ketchup.

Yeah, I am dancing around Frank.

I met Frank for the first time within my first few days in town, so August 1970. Leon drove us up Mount Sequoyah, one of the low, hilly mountains on either end of town, where Frank lived with his first wife in a little cabin. I have a few impressions left of that meeting—Frank grinning and pulling at his pants waist, saying of Linda “She likes her boy thin”; Frank talking about what he’d been working on; a couple of dogs loping about.

That first semester was about the only time I saw Frank with any regularity until after I had left town after graduating in 1974 and returned for regular visits, after 1975. He was in and out, had either left town after that semester or made himself scarce, or both. I know he did some traveling, spent some time on the road doing interviews with older poets, some time in New York, some time on the west coast with his Mill Mountain publisher. He made the short film It Wasn’t a Dream It Was a Flood in that time. Also during this time he and Linda parted, and he met up with Ginny somewhere on the road, eventually marrying her and moving into her family’s old farmhouse outside of Liberal, Missouri, just over the Arkansas border. But all that happened outside my range of vision, and by the time I reconnected with him, he and C. D. Wright had gotten together and he was living his double life, spending time in Fayetteville with Carolyn and time on the farm with Ginny.

So, backing up: Frank and the rest of the poets (by my arrival, Frank had stepped away from workshop) owned the university’s film series and brought in all the great old surrealist films, films noir, and European classics, and I’d see him at those screenings sometimes. Once I remember six of us, Leon driving and Frank and Linda in the backseat, went to a drive-in movie. I made the mistake of tripping and the proximity to my friends was, well, too much. There was another occasion when the two of them came to a little dinner Stoss cooked at the house we shared.

What I’m saying is all my early contacts were pretty ordinary, and between us it was like between any two shy people—friendly, reserved. The most electric time was at a party they threw for Alan Dugan’s visit, after Dugan’s reading. Frank had been really embraced by Dugan, and he (Frank) went kind of wild at the party, telling people off that he didn’t like, firing a shotgun into the ceiling. After that, which would’ve been in the spring of 1971, he pretty much disappeared from our lives. The Singing Knives came out around that time.

PD: It seems as if Stanford is an enigma in every interview or second-hand anecdote about him. Was he trying to cultivate for himself some kind of mythic status? Obviously his work makes it sound that way, but did he really think of himself as a poet that would last? Was he even able to separate himself from the work?

RA: That’s a tough set a questions, and goes to the heart of a lot of the fascination Frank seems to arouse. I can’t say whether there was deliberate self-mythologizing in Frank’s behavior. Was he thinking about how he would be regarded posthumously is what it comes down to, and I don’t know, though some of the evidence suggests as much. It’s a pretty weird thing, isn’t it—to try to prepare and control your own afterlife? We think when we read certain poets of the past that they did this, that there is a precedent that might have influenced Frank. And of course, as he was a person with astonishing gifts as well as the hidden mental health issues that often accompany such gifts, who knows what odd thoughts he might have entertained? But he was aware of how good a poet he was. I think he knew it innately, but even if not, the reactions of other poets would have tipped him off. He told C. D. that he had “perfect pitch” for language, and I think that’s an accurate bit of self-awareness. Did he believe in the longevity of his own work? Probably, yes. But was that any comfort to him? That’s the question I can’t answer.

PD: I'm sure that most people know the backstory of Stanford—quasi-orphan turned moon-drunk levee poet. Did he ever talk about his past in the way that his poetry seems to address it?

RA: For these questions, I am the wrong person. I gather from other people—both what some have said and others written—that he did, and that it was a real watershed when he found out that he was an adopted orphan. C. D., among others, has written about the profound effect this had on him, which she must know from his talking about it. I understand that he changed, that his outlook became darker. But whatever I know about this is secondhand. When he and I talked, it was all pretty much in the present.

PD: What drew you back to New Orleans? What was the poetry scene like here?

RA: Well, it was time to leave. I stayed an extra year, fighting with Miller about my degree. He had not liked my exit exam at all; it was a rebellious document and deliberately provocative as by then I was completely turned off to the “academy.” I survived on Poetry in the Schools gigs, and continued living with my girlfriend and working on my MFA manuscript. The best ten or twelve poems from that are in Sadness at the Private University, my first full collection, which Frank published through Lost Roads in 1977.

I probably never would have gotten out of there except for C. D. Wright going to Miller one day and saying, “Let him go” in her incredibly authoritative Arkansas drawl. I might’ve stayed just out of inertia except that my father was diagnosed with cancer, and I wanted to be home during his operation and treatment. But honestly, except for being glad to return to a handful of old friends, I was not really happy coming back here. I just didn’t have the ambition to seek any job anywhere, so I stayed, working at whatever I could find—a year in the Tulane Jazz Archive first, some renovation carpentry work (as a helper, not very skilled), a year working with old people under Jimmy Carter’s CETA program, a sort of junior WPA. In other words, a period of drift, of drinking too much, hanging out, becoming friends with Everette Maddox who was newly in town. So, the basic answer to your question is family, I guess, and this was home, so this is where I came back to.

There was not much of a poetry scene then, just slightly more than there had been when I left. Tulane had not yet hired a writer in residence; NOCCA hadn’t opened; UNO had some young writers but was years away from its MFA; there were almost no readings, certainly no series, though there was a sort of old-line poetry society that put on some. Louis Gallo had started Barataria Review, and he was responsible for some of the readings I did. Now there are more poets, and lots of good ones, more than we could have imagined in the mid-’70s. There is excitement and publishing at a very high level.

PD: Did Everette and Frank ever encounter one another?

It seems odd now, but I think Frank and Rette only met one time, though each knew about the other, certainly from me, as I am always promoting one friend to another. I know Frank and I went around to a few clubs, at least once to Tyler's (for several years the most exciting jazz club in town) when Astral Project was on—same band as now, but in their infancy. He was absolutely blown away. For all his love of modern jazz, I don’t think he had had the chance to hear that much live and these guys were (as they are now) incredible. We stayed to the end and he talked to them a bit afterwards. This comes back to me now as I recall the week of mourning in Fayetteville, when Ginny, Carolyn, several others and I sat in a little room talking about the funeral, reading from the script Frank had left (written in the final couple of days at Ellen Gilchrist’s house), where he specified that he wanted Astral Project to play at his funeral. Well, I called them—Ellen had offered to put up money to pay their travel and pay them to play—and we talked enough for them to understand the impact they’d had on him in his final days, to appreciate who he was, but they just couldn’t see their way to come up to Fayetteville and play. I can’t remember why now—other commitments maybe, maybe it was just too weird. But they didn’t come after what seemed like an exhaustive pitch by me.

But what I was getting at a moment ago was that in all that bar-going, I don’t think Frank and I were ever in the same place at the same time as Rette, except for one time: Frank and I had gotten off the streetcar at a bar on St. Charles with outdoor tables and we were sitting sipping a beer. Rette was either walking by or saw us from another streetcar and got off to join us, but either way, he showed up. It was definitely unplanned. At the time, early summer of 1978, Rette was in a bad way, having just been kicked out by his wife not too long before. He wouldn’t mind my characterizing his behavior as “pissing and moaning,” which is what it was, however justified, and that was all he could muster for conversation. Frank and I listened, commiserated, had a few more beers. When Rette finally got up and left, Frank looked at me and said—words I remember vividly as they became so portentous—“I could never live that way.”

PD: How did you reunite with Frank in the mid to late ’70s, especially enough for him to publish your first collection? I love the title of Sadness at the Private University. It seems to hint at what you've been speaking about—the conflict of home.

RA: We had lost touch after my first year or so in town. He was either away, which he was part of the time, or living outside the university axis. We had not been close then anyway, just together mostly with other people. I left Fayetteville in late summer of 1974, but started returning every few months, at first mainly to visit the girlfriend I had left behind. But she moved on to grad school in another state by late 1975, and then my visits were just to see friends—Steve Stern, Carolyn, a few others who were still around. When Carolyn began her relationship with Frank, that’s when he came back into my life as well. I stayed with them a few times; they came to New Orleans at least a couple of times. At least once, Frank came on his own, before that last time. Some of the memories are vivid: Once after I’d just gotten there and was standing chatting with Carolyn, Frank came through the room waving a top hat and cane and dancing; Carolyn said he was always doing things like that. One time they were staying in the apartment Ellen kept in Fayetteville (she’d stay for a spell working on her MFA, but spent more time at home in New Orleans, where she was still raising two teenagers); I remember this one more vividly because I was in such an extreme state myself, broke, with maybe one change of clothes, and, as always, they took care of me. They were about to start Lost Roads, which Frank envisioned as “a bookpress in magazine issue.” The plan, carried through the first 18 volumes, was to produce books that looked alike (except for the cover art), very plain otherwise, modeled after European books, I think.

I don’t quite remember when or how he asked for my book, which became Lost Roads #3. I gave him two manuscripts and he selected the twenty poems that are in Sadness. (There was one he selected that I didn’t want in, so I substituted another; I couldn’t tell you now which or why.) The title was the title of one of the poems; the cover art—a man being fed into an oven while evil spirits were flushed out—was something Frank found.

When copies were being shipped to me I talked to him on the phone and he said I “should have a weenie roast or something” to celebrate. I didn’t, though I did walk around in a cloud for a while when they arrived.

PD: Did Frank change at all from when you first met him?

RA: Well, everyone does in small ways, don’t they? But basically no, I don’t think so. What changed was that our friendship developed, though never what seemed like a really close one. I say it that way because I don’t really know what I was to Frank, or how he felt about our friendship. He was not very talkative, but he could be very funny. He was always observing, and he grinned a lot. When he was trying to make a point, he spoke very deliberately, frowning, carefully choosing words. But did he change from when I met him in 1970 to when I saw him last on June 2, 1978? I think maybe he had lost something from the first time to the last—that is, that he felt something was lost and could not be regained. Maybe it was just everything catching up with him, a kind of exhaustion—which makes sense when you read the first book (The Singing Knives) and the epic (The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You) and grasp how much he had already experienced, in life and in imagination, while still in his childhood.

PD: How was Lost Roads operating as a press in those days?

RA: Lost Roads was a labor-intensive operation. Frank, Carolyn, and a hired helper with printing experience produced those first eighteen books (the 540-page epic is counted as Lost Roads #7-12) on a letterpress they had acquired. Some funding came from the NEA, some came from Ellen Gilchrist. I can’t tell you much about the press except that. They put out an initial six books, then Battlefield, then a second six before Carolyn changed things up after Frank’s death. Really the last six were put out by Carolyn afterwards, though she and Frank had chosen the books—except for my second book, The End of the World, which became Lost Roads #17. The poet whose book was to be #17 withdrew when Frank died, and Carolyn asked if I had another one ready, which I did. Of course she kept it going through a large number of books with her poet-husband Forrest Gander as her partner, before giving it over to younger editors. Like most small presses, they were not very effective at getting books seen, bought, and reviewed, though they tried.

PD: Tell me about the last days. I've heard that he came down to New Orleans before flying back to Arkansas. Did you encounter him while he was here, and did he seem different?

RA: Yeah, his visit began around the middle of May, not too long after the May 3rd flood of 1978, which covered much of uptown New Orleans. He showed up seeming cheerful, unannounced. He sought me out the first day, but stayed much of the time in a basement room in Ellen’s big house on Webster Street. (I lived in a little half-shotgun also on Webster, about ten blocks closer to the river.) The ostensible reason for his visit was to work with Ellen on her poems, which became a Lost Roads book, The Land Surveyor’s Daughter. The more pressing reason seems to have had to do with his sense that things were not going well back home, where he was juggling his relationship with Carolyn with his marriage to Ginny. She was painting, significantly under Frank’s creative influence, and Carolyn was writing, also much under his influence. Carolyn knew about Ginny, of course, but Ginny did not know about the relationship with Carolyn. For some reason, the two of them got together while he was away, and both threatened to leave him. This is all pretty well documented in other places, so I won’t go into detail.

Frank spent some time writing a will, writing long letters to each of them. I even saw him doing some of that writing, sitting in one of Ellen’s living rooms. He seemed pensive, but not that distressed. He did change his return plane ticket several times, extending his stay rather than go back. We assumed he was putting off the confrontation and that may have been it initially, though in retrospect it seems as though he was putting off his suicide. But exactly when he decided to do that is not clear. We know he borrowed a small pistol when he got to town on the morning of June 3rd, and that the confrontation with Carolyn and Ginny was hard on all of them. And that he was dead by early evening, of the famous three shots to the heart.

Given what happened, it seems trivial to have mostly trivial memories of his two plus weeks here, but I remember walking, eating, talking, even a trip down to Bourbon Street. Frank also met and worked on poetry with a friend of Ellen’s, the late Kay Duvernay, who stayed with him overnight in my house his last night in town. She drove him to the airport the next morning before I woke up.

There are people who heard him declare that he would not live past thirty, that he would kill himself before. So the causes and circumstances of his death remain in a gray area. Would he have done it if he were returning to the status quo or even to happiness? This is unknowable, like so much to do with Frank, or with suicide.

PD: How have the years changed your opinion of Frank as a person and a poet? Has distance changed anything for you? I know that you've mentioned Frank in several of your poems or dedicated them to him.

RA: The night of June 3rd, when my friend Cheri came to my house to tell me (I had no phone, and someone had gotten word to her), I felt like the bottom had dropped out of the world. The night passed in a more drunken haze than usual, and I wound up sleeping on the floor of a commune house where Alabama friends of Everette’s were living. I bought a plane ticket in the morning and went to be with Carolyn and Ginny and everyone else there in a state of shock and mourning. My father drove me to the airport, obviously worried about me, and I remember telling him, “I never showed him any warmth,” which even now baffles me although it is true. Things were different enough in those days that when the stewardess came over to caution me about drinking any more of the bottle I’d brought, she wound up sitting next to me and having a drink in commiseration.

The week I spent there is etched in memory in about fifty discreet moments. Several days a number of us essentially camped out in Jim Whitehead’s house. Eventually we caravanned to Subiaco, where Frank had gone to school, and buried him there in the monastery grounds. There are stories to tell about that time, but not now, as I have already talked too much. Anyway, one day I’ll write that story myself.

It is not difficult to go back to that time and it feels as raw and powerful as it did then. I thought Frank was a great poet then, and do now. I think I have more reason to think it now, more understanding of how it is true, but it hasn’t really changed in kind. I am convinced that he lived a very intentional life, certainly more so than me, but also more than it seemed then.

The few poems I’ve written about Frank are not as revealing or interesting as the ones I’ve mentioned by my friends, his friends. Mine were felt, but they don’t do very much, I think. I am happier with the essay I was asked to write for The Asheville Review, for their issue in 2000 titled “Ten Great Neglected Poets of the Twentieth Century.” It still isn’t much, but it felt good to write it.

PD: Is there one thing that you could tell me about Frank that no one else knows or has previously told in an interview?

RA: Oh, there are a couple of things. (Realizing that makes me feel a little like a dog rationing his pee as he moves from tree to fence to car tire.) There was one small thing in that last visit: he told me about being really fond of a waitress in one of the little Fayetteville cafes; I can’t remember her name now but he made sure I heard it. I believe he was asking me to pass that message along to her, and I did, during that long week of mourning when we buried him. She was young and pretty, of course, and was grateful to hear what he had said about her.

One funny moment was when Frank came by my house, where I was sitting on the steps with a girlfriend. She asked him some pretty personal questions, including whether he had any kids and his answer was, “No,” and when she asked why, he said, “Just lucky I guess.” Of course, then, no one I knew had kids, or no one trying to write, even though we were hitting thirty.

Another time, Frank, Ellen, and I went to a place called Rosie’s on Tchoupitoulas St., a jazz club subsidized by its wealthy owner that brought in acts that could never be paid for by the cover, as the room was relatively small. Anyway, we’d parked across the street and were smoking a joint. When it got really small, I turned it around to “shotgun” smoke into their mouths, and it cracked Frank up when I did this; he looked up and said, “Look, Ellen, me and Ralph are kissing!”

During that last couple of weeks in New Orleans, I frequently had the feeling he was saying things deliberately, to be recalled. And there were some self-conscious gestures. The walls of my tiny bathroom in my little apartment were decorated with prints of figures from a book on the Sistine Chapel. On one of them was of a troubled looking man; I saw, after I got back from the funeral, that Frank had written on the side of the image, as though identifying it as himself, “What is Frank looking for?”

But I am not really the person to ask. Ginny or Carolyn would have thousands of small moments to tell. Some of the friends that he maybe fell out with a bit—Sam or Leon or John Wood—would probably have more robust stories. All three of those guys have written poems about Frank. And of course his old friends like Billy Willet. My memories are smaller and maybe less substantial; that they come from the end of his life is their only real distinction.

PD: Let’s shift to talking about your new book Ever. The poems here seem to be specifically about time, so much so that the sections are even divided into various aspects of time (Central Time, Sampling Time, Time Out). What role did time have in these poems for you? It seems especially important when you are talking about being a father at an older stage in life.

PD: Let’s shift to talking about your new book Ever. The poems here seem to be specifically about time, so much so that the sections are even divided into various aspects of time (Central Time, Sampling Time, Time Out). What role did time have in these poems for you? It seems especially important when you are talking about being a father at an older stage in life.

RA: I don’t mean to be pedantic, but time did have a way of asserting itself in the poems: they were written over a fourteen-year period, and I suppose that’s because it was on my mind. Not that it has driven me to do the practical things one ought to do, but certainly, the element of time in relation to my new duties as a father has been a kind of driving consciousness. But then time is a big deal in my 1979 book The End of the World, too—there in a more cosmic sense, a sort of wonder at the scope of it, the incomprehensible nature of it. My original title for the collection was Sampling Time, by which I intended the meaning of “sampling” as in the musical sense, as well as the idea that in living that is what we are doing, sampling portions of time.

PD: Many of the poems seem to be about understanding the self versus what the self has created, namely, children. I'm thinking about the poem “Lily Twice” where the last line ends with “I see only later.” What impact does seeing or reflecting on something have for you after the fact?

RA: The phenomenon is a familiar one to me: to see only sometime later what I might have and maybe should have seen in the moment. There’s also that definition of poetry—“experience recollected in tranquility”—at work here. It’s not the only way of looking at poetry, but it’s probably a pretty common experience for people writing poems.

PD: In “The Forgetting” you say that “the forgetting is ferocious and takes / all my time.” I think I have an idea of what you mean by this line, but I'd like to hear you elaborate on it, as well as on the poem overall. Also, the poem goes on to name those you've known that have passed (Frank and Everette among them). What does it mean for you to name the dead?

RA: This may be another function of aging, to have accumulated a lifetime of embarrassments, failures, moments or people disappointed, and I think that’s part of what I meant in that line. Then there are the things that are more painful than simple embarrassment or even failure, things that seemed at the time as though they would kill you and the mere fact that they didn’t does not diminish their painfulness or the suffering, leaving the act of “forgetting” as the only way forward. That poem, like a lot of the ones in Ever, is pieced together, written in different times and moods, and I suppose that part naming the dead is going in the other direction, trying not to forget, to keep the dead alive. I wasn’t conscious of it at the time, but I would say that part of the poem probably comes from some lines in Archibald MacLeish’s poem, “Epistle to Be Left in the Earth,” where he says: “you, if any read this writing, / make in your mouths the words that were our names.”

PD: In the second section of the book, you have a poem titled “Being Moved While Moving (or Longing for Landscape)” which reads as an almost anti-love poem. Would you consider this a love poem or not? What does it mean to you to be “grateful and sad and burning with joy?”

RA: Yes, that’s my version of a love poem—that aspect of love that involves appreciation and respect. Like most of the poems, it is full of private references that I am hoping will have some more universal resonance. Certainly the conclusion is addressed to Kay and the fact of our having these children to love and take care of. As for the line you quote, I suppose I was trying to capture the contradictory nature of the way we experience things, especially when we experience them intensely.

Also, I need to add, that is one of the few poems in the book that arose from an exercise—in this case, one that I have given my students in the summer program where I have taught the past seven Junes. There is a poem by the Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet (which I found in Carolyn Forche’s wonderful anthology, Against Forgetting: The Poetry of Witness) called “Things I Didn’t Know I Loved” that was the inspiration for mine, which I wrote while the students were writing theirs.

PD: I love the “Dark Poem” in Part Three of the book—it’s both funny and poignant. How did you come about writing this poem, and what do you mean by the epigraph “On Belief and In Faith”?

RA: Thanks, yes, I meant for it to be at least a little funny, but it’s hard to get a laugh when I use it at a reading. That one was written all at once and fairly quickly. It’s kind of a riff poem. I wrote it one night when the power went out and we were left in the dark with none of our usual machines to keep us company. As for the epigraph, I’m not sure; once I’d written the poem it struck me as being something like a religious tract, and the epigraph just seemed to belong there.

PD: The poem “Glacial Volant” is unlike some of your other poems in that it deals with an abstract state. And yet, there are lines that seem conversational: “How do you keep your friends when / you have no faith / and can't remember your dreams.” What made you decide to blend these two modes together?

RA: That’s a poem that maybe looks like it was written all at once but in fact was written over a several-year period. There are allusions to Eliot and Nabokov in it, for what that’s worth. But I don’t really have an answer for why I blend the conversational with the kind of tortured abstract. You probably noticed that there is a tendency in a lot of these poems to mix modes, most obviously the poems that have free verse sections butted up against almost doggerel sections of rhyming verse. So it just seems normal to me that things that may not seem to belong together are juxtaposed.

PD: Part Four, “After All, a last gasp,” is like a jazz song. You experiment with form, language, rhyme, and content by moving in and out of time and voice until the speaker of the poem ends on the comparison of a tap dance, to where he is slowly “tap taptappity taptapped out.” I was wondering if you could elaborate on these ideas—what made you decide to place this as the last poem in the collection?

RA: I love that comparison to a jazz song, thank you. The last poem picks up a lot of themes and styles from the rest of the book—it works for me, anyway, as a proper kind of epilogue, although I did not want to call it that. Parts of it are some of my favorite things in Ever, though. The title does sum up the way I felt then, that the whole book had been a sort of prolonged wheeze and this now was the “last gasp” of that wheeze. Not a very pretty image for poetry, I guess. As for the taptapitty bit, it is partly, as you identified, a kind of tap-dance exit, and also a reference to the gambler being “tapped out.” And also phonically, an allusion to the sound of the keyboard (which we rarely or never hear anymore, or hear only faintly on our computer keyboard) as distinct from the old typewriter, which is more what I am alluding to there.

I also knew, somehow, that that was the end of the book, and it was—no more poems came peeking or poking their way out. In fact, the few times that I’ve been tempted to write since, I have either squelched the impulse or produced something I didn’t like. I want to write some essays before I return to poetry. And I am hoping for a different direction when I do return, different themes or formal directions, certainly. Not that those things can be controlled, quite. Willed a little, maybe.

PD: Where do you think your writing will go in the future? How do you want to be remembered as a poet?

RA: Tough questions. I have made a conscious effort since concluding Ever in late summer this year to not write any poems. I have instead begun a number of essays, all still unfinished, and of course, continued with my new vice of commenting in the Times Picayune’s online news site, speaking up politically and engaging in what are certainly useless fights with people who are almost all hiding behind pseudonyms—I post under my name. Not that I think this is the future of my writing, but it keeps me typing words, anyway.

Time is my big problem; I am low on my allotted time as I age, and working, teaching, editing, and raising kids doesn’t leave much time—time that is mine for stretches, without obligations or interruptions, to do with what I will. Though this sounds like a complaint, it is also true that I love the things that take up my time, my kids most especially, and so I wouldn’t really want to not have this problem.

As for being remembered as a poet, that would be up to a few specific poems, wouldn’t it? Isn’t that the way we mostly remember even the great poets with deep bodies of work? Or at least that’s the way I tend to. I hope I have written some things that people want to read, now, later, whenever. I hope I have done at least some little good with my life and not only as a writer.

A sabbatical would be nice, but as an untenured teacher, I can never have one. I also don’t seem to have any luck with granting agencies, which might provide support for some time anyway. Ever is the product of fourteen years, and it only comes to 80 pages. So the future is hard to imagine, much less predict. I think when I do begin writing poems again, they will be very different from what I’ve done. I think Ever was the end of my long beginning in poetry, and that now, maybe, finally, I will write poems that sing a richer song.

Frank Stanford

Frank Stanford

by Paul Dean

by Paul Dean PD: You mentioned Dylan, and I'm glad you did. I first started to write seriously when I discovered his albums. What resonated with you in Dylan's work? Was it the politics or the poetry itself?

PD: You mentioned Dylan, and I'm glad you did. I first started to write seriously when I discovered his albums. What resonated with you in Dylan's work? Was it the politics or the poetry itself?

Joseph Harms

Joseph Harms