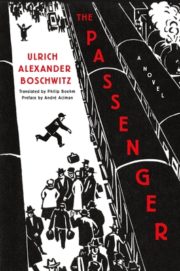

Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz

translated by Philip Boehm

Metropolitan Books ($24.99)

by Chris Barsanti

In one of many unnerving scenes in Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s eerily prescient novel The Passenger, set in November 1938, German Jewish businessman Otto Silbermann rides on yet another train that he hopes will bring him to safety. Silbermann is on the run in a country crawling with Gestapo, brownshirts, and Gentile citizens all too eager to volunteer their services to the National Socialist dragnet, and he is reaching the end of a rapidly fraying rope. In desperation, he riskily reveals his identity to the attractive woman sharing his compartment, setting into motion a quasi-absurdist chase narrative in which the man on the run is knocked from one dead end to another by forces not only out of his control but beyond his ken.

At first, the encounter goes better than expected; the woman on the train seems friendly and more concerned for his plight than any other non-Jew he has encountered. But as their talk progresses, she shows signs of irritation and boredom, asking, “Why do the Jews put up with all of this?”—a question echoed in later years by many others who would likely not see themselves as anti-Semitic. Silbermann pushes back against her allegations of spinelessness, arguing that, “If we were such romantics . . . we would have had hardly survived the last two thousand years.” The irony of his logic is that to some degree, he is a romantic. When she asks him whether “survival is so important” he answers, “Absolutely!” But the peregrinations of his chaotic and error-prone flight to freedom show that for him, survival itself may not be enough. He seems almost more driven to run by the degradations and humiliations imposed by the regime and a complicit citizenry eager to steal what little he has left than by the will to save his own life and be reunited with his family.

Composed in a feverish four weeks by twenty-three-year-old Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, The Passenger mirrors the author’s experiences as a German Jew whose family fled the country after the passage of the racist Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Like Silbermann, Boschwitz was constantly on the move in a world that had dispiritingly limited sympathy for refugees like himself. When originally published in 1939, The Passenger attracted little notice despite its burning timeliness. After all, even as the Nazis were openly rounding up Jewish citizens in the post-Kristallnacht smoke and rubble, a good part of the world was ignoring or actively dismissing the genocide-in-the-making. This new, long-overdue edition is based on the rediscovery of Boschwitz’s original German typescript and incorporates edits he had wished to make, highlighting the protagonist’s halting efforts to leave a country he now knows he should have departed months if not years before.

No escape artist, Silbermann is thwarted by panic, confusion, bad luck, and eventually a creeping thread of self-destructive despair. A prosperous businessman with a Protestant wife, Silbermann wonders to himself how “I’m living as though I weren’t a Jew” even though the tide of hatred has turned him into “a swear word on two legs.” Seeing a newspaper headline that reads “Jews Declare War on the German People,” he considers it a bad joke: “I was fully aware that war had been declared, he thought. But that I’m the one declaring it is news to me.” Like many people in his position throughout history, he cannot comprehend that his humanity can be legislated out of existence so simply.

Similarly, Silbermann cannot believe his fellow Germans will turn on him, even as pogroms and newly restrictive laws sweep the country and opportunists swoop like vultures to take advantage. Silbermann’s boorishly odious Gentile business partner Becker is vocally anti-Semitic and seems on the verge of absconding with the money Silbermann needs to flee Germany. Findler, the realtor blackmailing Silbermann for a low-ball price on his property even as the brownshirts are pounding on the door, worries only for himself: “They might take me for a Jew and smash my teeth in.” Still, our hero hangs on to some notion of these men’s inherent decency. While Silbermann’s insistence on bright-siding this catastrophe may make sense from a self-protection standpoint (trying to keep panic at bay), Boschwitz is also purposefully showing how so many Germans gleefully took part in the looting, knowledge that much of the world did not have until decades after the Holocaust.

The Passenger shows the heat and speed of its composition. A number of its conversations can feel repetitive, while Silbermann’s state of mind is not always clearly conveyed. But Boschwitz has a knack for illustrating a particular brand of racist self-delusion in which the non-Jewish German characters deny any responsibility for the dark forces harrying Silbermann. Like the woman to whom he opens himself up, they are uninterested in what happens to him, blame him for what is happening, or see no moral responsibility to help.

Even after publishing this novel, Boschwitz continued to be shuttled around in Silbermann-like fashion. He spent the early part of the war classified by the British as an “enemy alien” and was interred on the Isle of Man; later he was sent to Australia with Nazi sympathizers. Reclassified as a “friendly alien” in 1942, he was put on a ship back to England (where his mother lived); he and 361 others died when the ship was sunk by a Nazi U-boat. It is hard to imagine a more tragic end for an author who wrote with such adroit understanding about the mundane madness that lies behind genocidal cruelty and arbitrary classifications.