Leah Naomi Green

Leah Naomi Green

Graywolf Press ($15.99)

by Todd Davis

How to speak of the self when the self, as Whitman proclaimed, contains multitudes? How to conceive of a self as part of another being, literally co-dependent, not able to exist without the other?

The Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh explains that “interbeing” is the idea that we can never “be” by ourselves; rather we are always in a state of “braidedness,” woven together in symbiosis. Science similarly tells us that we are composed, biologically, of other living things that make our lives possible. As Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, expounds in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, “Recent research has shown that the smell of humus exerts a physiological effect on humans. Breathing in the scent of Mother Earth stimulates the release of the hormone oxytocin, the same chemical that promotes bonding between mother and child, between lovers.”

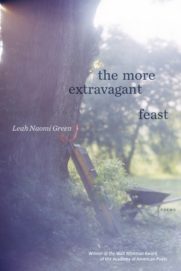

Held in the arms of the greater-than-human world, Leah Naomi Green is such a lover of the earth, a writer who seeks to care for creation and to raise her family in mindful connection with it. These most basic foundational tenets are at the center of her stunning and sumptuous debut collection, The More Extravagant Feast, selected by Li-Young Lee as the winner of the Walt Whitman Award from the Academy of American Poets. The book is a deep and reverent meditation on the fact that we are never solely our own, that our lives are always cohabitating with the lives of others—both human and more than human.

Told in a language that celebrates compassion, empathy, and a path of loving kindness, the poems here offer our precarious and dire present moment possible paths forward via an ancient way of seeing that can still inform 21st-century living. As Green writes in “Week Ten: Plum,” an origin story about the child that grows inside of her:

My body, which has never died,

has two hearts again today,

and how many

inside the second?

Green demonstrates a remarkable gratitude for all life, reminding us that our existence begins within the body of another, floating on an amniotic sea, our mothers’ hearts beating for us. From our first moments, we rely on the help of others to live, to survive.

Throughout the collection, Green addresses the world around her, even the carrots she grows, urging the tubers to “take all summer, / your ember // from the sun, / its walking meditation” (“Carrot”). She is one of those rare seers, perceiving the hidden and translating it so it becomes illuminated and luminous. To this end, she uses juxtaposition as a primary poetic device, showing us the vital and intimate relationship between what might be perceived as unlike or unassociated:

The fire beetle only mates

when the chaparral is burningand the water beetle

will only mate in the rain.In the monastery kitchen, the nuns

don’t believe mewhen I tell them how old I am,

that you were married before.The woman you find attractive

does not believe me when I look at her kindly.

(“Field Guide to the Chaparral”)

Even her line and couplet breaks emphasize how each revelation, each statement, blends into the next in unexpected ways that turn to realization, even epiphany, about the correlation between one living being and another.

Green, along with her husband and two children, live in an intentional community in rural Virginia. They raise and hunt most of the food they use throughout the year, living close with the daily rhythms of the greater-than-human world. In this setting the poet strips away the superfluous structures erected to divert our attention from the essential relationships humans have fostered with the earth and each other for millennia. And her book recounts myriad moments of union: some quiet, others startling in the violence nature possesses.

The work can be visceral and unflinching. In “Venison,” she and her husband collect a deer hit by a passing car:

The deer is still alive

in the roadside grass.

In an hour, we’ll cut her open,

her left hip broken . . .

Later, as she watches her husband “undress” the deer with a knife, she describes the sound:

I can hear

his blade unmoor muscle, sail

through her fascia

Green takes care to name this aspect of the world, to report in detail, to make the smallest moment live again inside the borders of her poem, in order that the recognition she offers not become a simple gloss. And so the poem closes with a lived authority, acknowledging the suffering of the boy whose Camaro struck the deer, the difficulty of witnessing the end of a life, the hard work that must be endured as her husband butchers the animal so a life is not wasted:

We put her leg and buttock

on the wooden table, where we

will gather her between us

to eat all year. It is all I see:

a thing, alive, slowly becoming my own body.

In “The More Extravagant Feast,” which serves as the collection’s final poem, Green speaks of the miracle of her daughter’s lungs “that grew inside me”; “the miracle // of her dad on the hill”; “the miracle / of bodies, formed whole like fruits, // skins unruptured and / containing the world.” Her explorations provide daring correlations and important reminders of the miraculous nature of existence. What marks her work as not only a refreshing balm but as a way forward is her ability to praise and offer graceful thanks, to highlight how all living things are allied and related.

Not all poetry is as deeply connected to lived experience as Green’s. But her commitment to a way of life beyond the page informs the wisdom written on the page, demonstrating how care for one another, the human and greater than human, is a path toward a much needed wholeness and preservation.